- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

With all due respect to T.S. Eliot and his grim assessment of April, it’s August in Sacramento that can be “the cruelest month” for ambitious lawmakers.

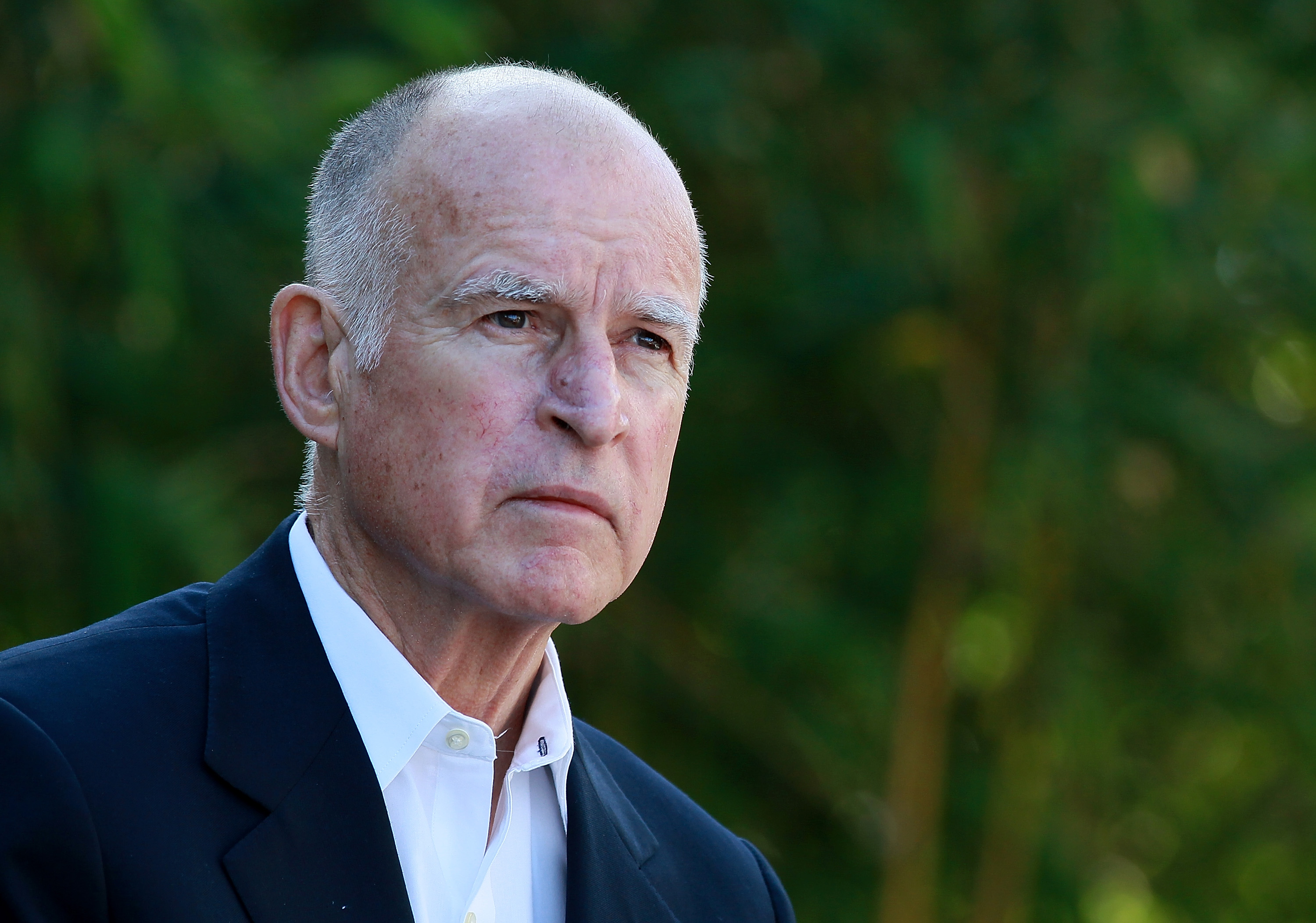

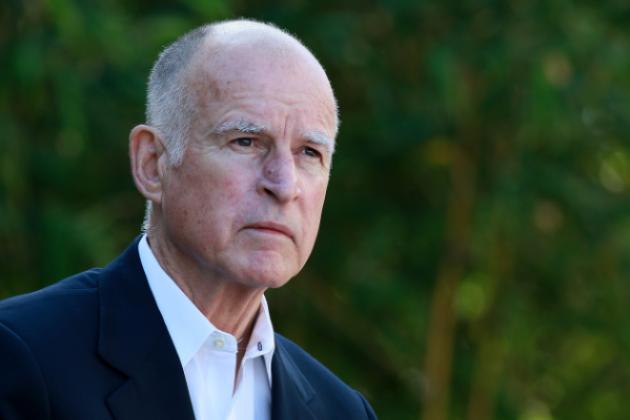

It’s not so much the state capital’s Hadean heat that makes for the rough going (coupled this year with poor air quality courtesy of the Northern California wildfires). Rather, it’s getting schooled in the art of political management by one Edmund Gerald Brown Jr.—aka, Jerry Brown, now in his final year as California’s longest-reigning governor.

In early August, California’s State Legislature returned from its summer vacation for one last flurry of policy making. This prompted plenty of speculation: what will the governor sign; what will he veto; and what gets tabled until next year?

The drama’s especially rich this year, as at least four policy/political elements will collide in this abbreviated work session.

These include:

- the desire to show productivity in an election year;

- a progressive legislature with a big appetite;

- a not-so-progressive governor in search of legacy embellishment; and

- a new governor and new working relationship in store for 2019.

Of those four factors, it’s the third—Brown’s legacy (he hates that word, btw)—that bears watching.

Why? Because the governor has at least two splashy bill signings in mind for his remaining days in office: replacing the main California power-grid operator with a multi-state entity and a “Waterfix” that would tunnel north and south beneath the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (ironically, building on the State Water Plan begun by Brown’s father, the legendary Pat Brown, in the 1960’s).

Will Brown get his way on both matters? If he does, it’s further testament to his alpha skills as a California governor.

There’s an old saying in Washington: “the President proposes, the Congress disposes.” The Sacramento version: “the Legislature intends, the Governors superintends.”

What I mean by that: California governors hold unusual sway over the policy-making process given that their vetoes rarely are overridden (one has to go all the way back to 1979 and a Jerry Brown veto of a pay increase for state workers for the last time California’s Legislature defied a governor’s will).

Brown has another ace up his sleeve: a superior working knowledge of the place. Brown’s currently in his sixteenth and last year as governor. During these last two of his four terms, he’s collaborated with three assembly speakers and three Senate Presidents pro tempore. Simply put, name the policy pas a deux and chances are Brown has more knowledge than his legislative counterparts and more hands-on experience.

Third, Brown understands nuance. This wasn’t the case nearly two decades ago when then-governor Gray Davis made the error of telling reporters, soon after he took office, that the legislature’s job was “to implement my vision” (from the legislators’ perspective, the equivalent of a wife being mansplained about who wears the pants in the family).

How does nuance work in Sacramento? In 2011 and his first year back on the job, Brown vetoed the first state budget forwarded from the legislature. Why? To send an unmistakable message that he was dictating fiscal terms. Fast-forward to 2018 and Brown’s final budget: the governor didn’t issue a single line-item veto, a sign of both a healthy surplus and the legislature respecting the governor’s spending wishes.

Another example of Brown’s skills at political nuance: stifling single-payer health care. Last year, the Democratic-controlled legislature clamored for it. Brown halted the effort with one simple question: “Where do you get the extra money?”

There’s one characteristic that’s elevated Brown’s alpha-dog status in Sacramento: his nonconformity. This is, after all, the governor who once observed, via his veto pen: “Not every human problem deserves a law” (this was in response to a bill imposing a $25 fine on minors caught not wearing a helmet while skiing and snowboarding).

Brown’s also the rare case of a Democratic governor who doesn’t always see the world through the same progressive prism as his fellow Democrats in Sacramento. Every year the California Chamber of Commerce produce a list of “job-killer” bills deemed harmful to the Golden State’s economy (here’s 2018’s batch). By the Chamber’s count, Brown’s vetoed 125 of the 135 bills that fell under this category over the past five years. In the California scheme of things, that’s closer to Pete Wilson than Woodrow Wilson.

That nonconformity likely changes in 2019 if Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom succeeds Brown as California’s fortieth governor (it’ll be the first time in 130 years that California has had consecutive Democratic governors).

Newsom is decidedly to the left of Brown on some key Democratic issues (most notably, bringing a single-payer system to life). He’s also never served in the state legislature and, though holding a Sacramento-based office these past eight years, isn’t steeped in dealmaking as he’s spent much of his time as lieutenant governor touring the state and laying the groundwork for his gubernatorial run.

In other words, the Democratic legislative leadership could decide if the going gets rough in the coming days: rather than haggle with Brown, let’s just wait five months and work with the new guy.

The dynamic is somewhat akin to what California faced in 1999 when the state saw its first Democratic governor in sixteen years. The state legislature, stymied by two previous Republican administrations, champed at the bit to put its progressive agenda into play. The newly-elected Gray Davis, hampered in part by that unfortunate remark about vision implementation, struggled to maintain control of the stampede.

Call it not a legacy item but a generous parting gift: Jerry Brown showing his successor what it takes to become Sacramento’s alpha dog.