- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

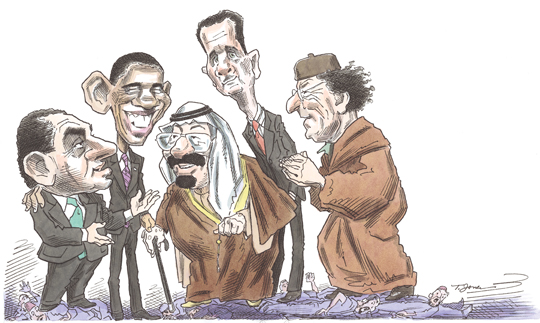

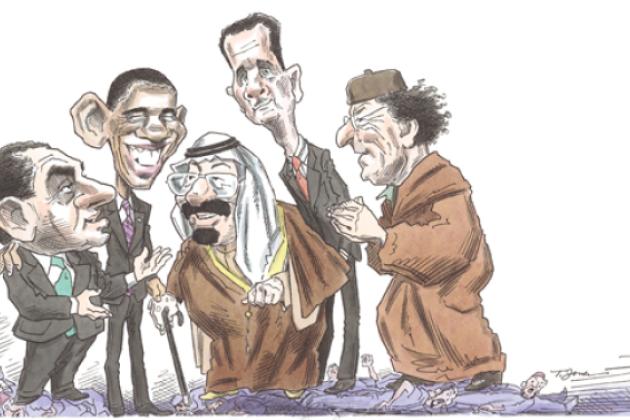

“To the Muslim world, we seek a new way forward, based on mutual interest and mutual respect,” said President Barack Obama in his inaugural address. But, in truth, the new way forward is a return to realpolitik and business as usual in America’s encounter with the greater Middle East. As the president told Al-Arabiya television in one of his first interviews, he wants a return to “the same respect and partnership that America had with the Muslim world as recently as twenty or thirty years ago.”

Say what you will about the style—and practice—of the Bush years, the autocracies were on notice for the first five or six years of George. W. Bush’s presidency. America had toppled Taliban rule and the tyranny of Saddam Hussein; it had frightened the Libyan ruler into believing that a similar fate lay in store for him. It was not sweet persuasion that drove Syria out of Lebanon in 2005. That dominion of plunder and terror was given up under duress.

True, Bush’s diplomacy of freedom fizzled out in the last two years of his presidency, and the autocracies in the greater Middle East came to the conclusion that the storm had passed them by and that they had been spared. But we are still too close to this history to see how it will work its way through Arab political culture.

The argument that liberty springs from within and can’t be given to distant peoples is more flawed than meets the eye. In the sweep of modern history, the fortunes of liberty have been deeply dependent on the will of the dominant power or powers. The late Samuel P. Huntington made this point with telling detail. In fifteen of the twenty-nine democratic countries in 1970, democratic regimes were midwifed by foreign rule or had come into being right after independence from foreign occupation.

In the ebb and flow of liberty, power always mattered and liberty needed the protection of great powers. The appeal of the pamphlets of Mill and Locke and Paine relied on the guns of Pax Britannica, and on the might of America when British power gave way. In this vein, the assertive diplomacy of George W. Bush gave heart to Muslims long in the grip of tyrannies. Consider the image of Saddam Hussein, flushed out of his spider hole some five years ago: Americans may have edited it out of their memory, but it shall endure for a long time in Arab consciousness. Rulers can be toppled and brought to account. No wonder the neighboring dictatorships bristled at the sight of that capture and at Saddam’s execution three years later.

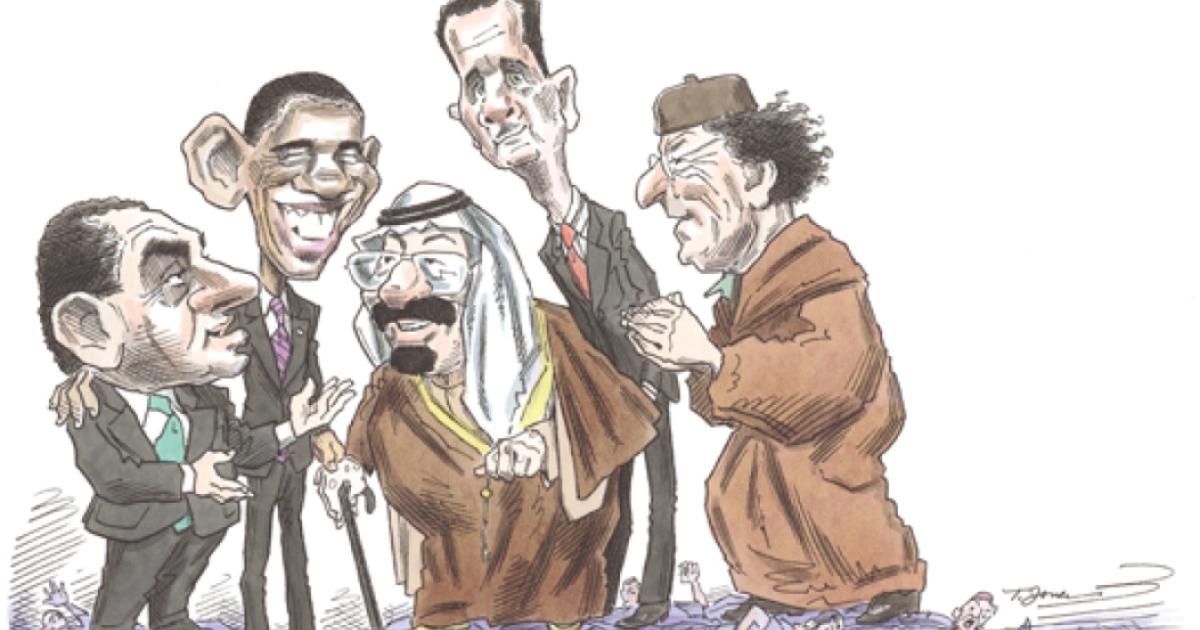

The irony now is obvious: Bush as a force for emancipation in Muslim lands and Barack Hussein Obama as a messenger of the old, settled ways. Thus the “parochial” man took abroad a message that Muslims and Arabs do not have tyranny in their DNA, and the man with Muslim and Kenyan and Indonesian fragments in his very life and identity signals acceptance of the established order. Obama could still acknowledge the revolutionary impact of his predecessor’s diplomacy, but so far he has chosen not to do so.

His brief reference to Iraq in the inaugural speech could not have been icier or more clipped. “We will begin to responsibly leave Iraq to its people,” Obama said. Granted, Iraq was not his cause. But a project that has taken so much American toil and sacrifice, that has laid the foundations of a binational (Arab and Kurdish) state in the very heart of an Arab world otherwise given to a despotic political tradition, surely could have elicited a word or two of praise. In his desire to be the un-Bush, the new president has fallen back on an austere view of freedom’s possibilities. The foreign world is to be kept at an emotional and cultural distance. Even Afghanistan—the good war that the new administration has accepted as its burden—evokes no soaring poetry, just the promise of forging “a hard-earned peace.” Yet Americans cast their votes for a new way.

Where Bush had seen the connection between the autocratic ways in Muslim lands and the culture of terror that infected the young foot soldiers of radicalism, Obama seems ready to split the difference with their rulers. His embrace of the “peace process” is a return to the sterile diplomacy of the Clinton years, with its belief that the terror is rooted in the Palestinians’ grievances. Obama and his advisers have refrained from asserting that terrorism has passed from the scene (although the phrase “war on terror” has disappeared from their lexicon), but there is an unmistakable message conveyed by them that we can return to our own affairs, that Wall Street is more deadly and dangerous than that fabled Arab-Muslim “street.”

Thus far Obama’s political genius has been his intuitive feel for the mood of this country. He bet that the country was ready for his brand of postracial politics, and he was vindicated. More-timid souls counseled that he should wait and bide his time, but the electorate responded to him. I suspect that he is on the mark in his reading of America’s fatigue and disillusionment with foreign causes and foreign places. That is why Osama bin Laden’s recent call for a “financial jihad” against America seemed so beside the point; the work of destruction has been done by our own investment wizards and politicians.

But foreign challengers and rogue regimes are under no obligation to accommodate our mood and our needs. They are not hanging onto news of our financial crisis; they are not mesmerized by the fluctuations of the Dow. I know it is a cliché, but sooner or later, we shall be hearing from them. They will strip us of our illusions and our (new) parochialism.

A dispatch from the Arabian Peninsula bears this out. Even as Obama issued his order that Guantánamo be shut down in a year’s time, news came that a Saudi named Said Ali al-Shihri (detainee number 372)—who had been released from that prison in 2007 to his homeland—had made his way to Yemen and risen in the terror world of that anarchic country. Detainee number 372‚s stop in Saudi Arabia was brief: he went through a “rehabilitation” program there and then slipped across the border to Yemen, where he may have been involved in a terror attack on the U.S. embassy in the Yemeni capital last September.

This war was never a unilateral American war to be called off by an American calendar. The enemy, too, has a vote in how this struggle between American power and radical Islamism plays out in the years to come.

In another time, the fabled era of Bill Clinton’s peace and prosperity, we were mesmerized by the Nasdaq. In the watering hole of Davos, in the heights of the Alps, gurus confident of a new age of commerce pronounced the end of ideology and politics. But in the forbidding mountains of the Afghan-Pakistan frontier, a breed of jihadists that paid no heed to that mood of economic triumphalism was plotting for us an entirely different future.

Here we are again, this time led by our economic distress, demanding that the world abide by our own reading of historical challenges. We have not discovered the sweet spot where our economic fortunes intersect with the demands and challenges of an uncertain world.