A mass drugging is how one young Saudi man in Riyadh described to me Mohammad Bin Salman’s Vision 2030, eight months after its ostentatious launch in April 2016. Smoke and mirrors, he meant. Since then, the energetic and youthful Saudi crown prince has surprised his critics by upending a number of his country’s political, economic, and cultural norms. But can he safely deliver more change to an already rapidly changing society? How much tinkering can one do with a fragile polity before it cracks under the pressure?

Bin Salman’s first and most consequential move was to get himself installed as heir to the throne. His cousin Mohammad Bin Nayef broke through the conceptual barrier by being the first of the grandsons of Abdul Aziz to be positioned for direct succession, but his status proved tenuous. The uncertainty concerning the precise path of transition from the generation of the sons – who have ruled the kingdom since 1953 – to the generation of the grandsons was resolved in decisive fashion with Bin Salman’s ascent.

The Saudi crown prince’s neutering of the kingdom’s commercial elite in the now famous Ritz Carlton roundup took the world by surprise. Bin Salman’s maneuver shattered the traditional laissez faire approach to business in the kingdom, whereby the royal family gave the commercial elite room to manage the private sector, while skimming regular tithes off of the top. The business leaders who were targeted in the November 2017 crackdown were influential figures, but they were not particularly threatening, since they do not possess a large and potentially adversarial social constituency in the way of Saudi religious scholars or tribal leaders. This has in part to do with their predominantly Hijazi origin, and in part to do with how the state, an absolute monarchy, has structured politics to privilege certain quasi-political actors and exclude others. In short, clipping the wings of those captains of commerce and patronage, though shocking, was not particularly difficult for Bin Salman.

Whereas fat cats have been purged under the new regime, local tribal and clan leaders have been empowered. Two years before the so-called corruption campaign, in the midst of a significant economic contraction, King Salman announced that he would institute regular monthly stipends for local tribal leaders, who number in the hundreds, if not thousands. In June 2017, the lowest level of tribal functionary began receiving stipends of no less than $1000 per month to serve as informal security liaisons for the state in local, often rural, Saudi communities. Saudi tribal groups, particularly the large formerly nomadic confederations such as Anaza, Shammar, and Utayba, endure as reminders of alternatives to the Saudi political order, and so the expectations of their members, both commoner and elite, must be managed diligently. The princes who rise to the top of the family pile know this lesson intuitively, and Bin Salman’s salt-of-the-earth manner certainly does not hurt him with that segment of the Saudi populace. At a comparative level, the contrasting treatment of these two royal constituencies, the business elite and the local tribal or clan leaders, sheds some light on how the often-inscrutable monarchy evaluates potential domestic threats.

Despite the endless tomes of religious commentary they produce, the Saudi ulama remain an inscrutable status group, whose relationship to material power and splendor is at best uneasy. While historically the ulama have been well coopted, the crisis of authority they face today is more severe than in earlier times. In exchange for their acquiescence to the twentieth century, Saudi court’s sometimes-impious political decision making, the Wahhabi ulama were given significant control over the social and legal spheres. Bin Salman’s recent move to liberalize Saudi public culture and provide a measure of empowerment to Saudi women overtly challenges the ulama’s traditional monopoly. How they will react over the long term is anyone’s guess – will they liberalize, reinforce their quietism, or prove Khomeini-esque?

However they respond, the ulama will face a chorus of newly energized voices – Saudi women. Undoubtedly, the young crown prince’s most astute move has been his effort to reset the public norms, expectations, and laws governing the place of Saudi women in public life. With this long overdue though still courageous break from an unjust status quo, Bin Salman has created an instant constituency of massive proportions, one that has a personal incentive to promote his liberalizing reforms within diverse segments of the Saudi population, including those generally less supportive of gender equality, for example, traditionalist religious figures and many family patriarchs. The Saudi regime’s arrest of seven female activists just weeks before the lifting of the driving ban, however, diminishes the crown prince’s progressive credentials, even as it reaffirms the royal family’s broader strategy of positioning itself as the sole legitimate provider of social benefit or sanction.

It is commonly suggested that Bin Salman has taken his radical measures in order to capture the loyalties of Saudi youth, who comprise approximately three-fourths of the country’s population. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the crown prince’s reform drive has been greeted enthusiastically by most young Saudis. Yet this mass of youth is by no means undifferentiated. Young people in Saudi Arabia are not all signed on to a liberalizing project for their society. Whether on account of religious, rural, or otherwise conservative norms, resistance to rapid material change exists. Such resistance may not be diminished through the mix of economic growth and increasing social freedom currently on offer, but may in fact be unleashed by it. Islamic State’s appeal among a sizeable number of disaffected Saudi youth signifies this potential for malice in the body politic, even though it does not appear sufficient to stymie the crown prince’s best-laid plans.

The challenge of reform extends to the kingdom’s security and foreign policies, too. Historically, the Saudi monarchy feared internal uprisings originating in the state’s security services. So it spread its military installations to the far corners of the kingdom, while distributing authority across often rival and redundant security forces, thereby gumming up any coup prospects. The regime’s coup-proofing strategy resulted in a severe reticence to commit significant troops to conflicts beyond the kingdom’s borders. That, too, is changing. As a response to the Arab Spring uprisings in Bahrain, King Abdullah dispatched SANG troops to shore up that vulnerable regime’s position. The late king also briefly deployed Saudi air power against the Houthi rebels in 2009. The ongoing Yemen war thus represents an extension of a policy launched almost a decade ago to more aggressively pursue Saudi regional interests with military force beyond the kingdom’s borders.

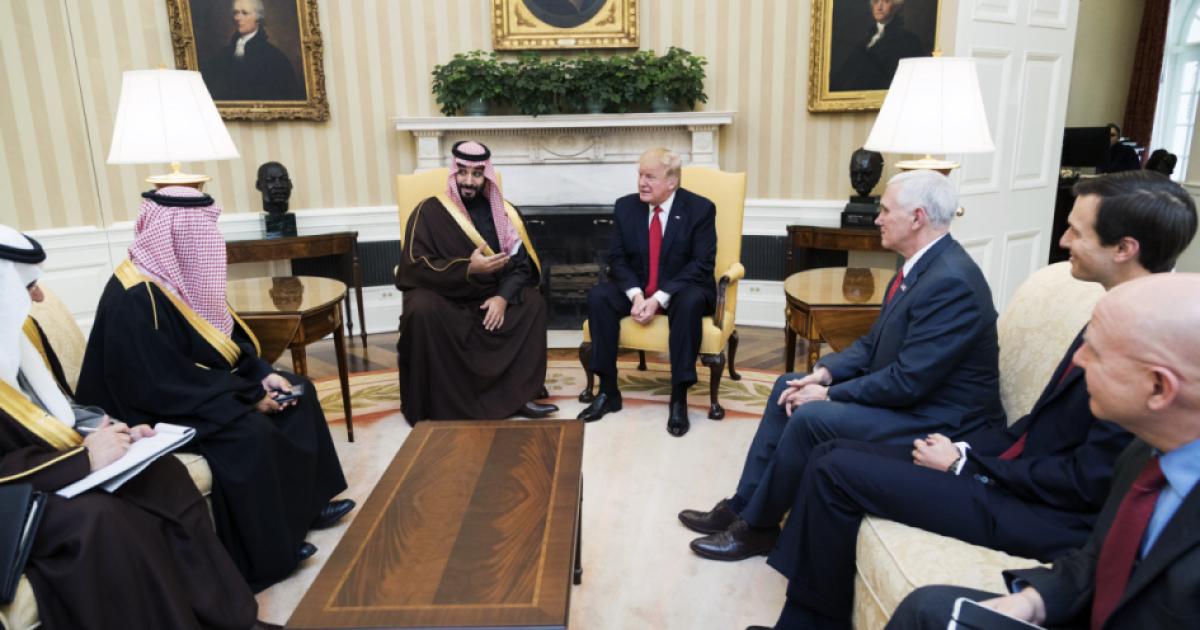

Yet the Yemen war has been largely a prolonged air campaign; the Saudis have not committed ground troops to the offensive against the Houthis in Yemen, except for border defense. If Saudi citizens were to be mobilized en masse in a ground invasion of Yemen, the aftermath of that bloody campaign could mark the beginnings of popular nationalist pressures on the Saudi state. This strategy of partial committal helps explain why the Yemen conflict is dragging on without an end in sight. It is the military strategy of a state with relatively weak legitimacy, the consequence of which is to exacerbate and prolong the suffering of Yemeni non-combatants. America’s reaffirmation of its strategic relationship with Saudi Arabia can help put an end to the war in Yemen. The US should leverage its strengthening ties with Saudi Arabia to broker a resolution to the Saudi-Yemen war that preserves Saudi deterrence against Iranian proxies while bringing lasting relief to Yemen’s embattled citizens.

The US’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal presents Bin Salman with one of his biggest challenges to date. The tension between these regional adversaries has been building since 1979, with few periods as volatile as the present. Talk of regional war looms. Yet the governments of Saudi Arabia and Iran are both rentier oil state regimes that dominate their own domestic economies; this makes them more alike than they care to acknowledge, beholden equally to larger geopolitical and energy market forces that encompass and ultimately diminish the volatility of their rivalry – so long as a stable world order persists. For its unambiguous recognition of this reality, Saudi Arabia has historically been the wiser of the two rivals. With his heavy handed charm offensive for Western and Saudi audiences, Bin Salman has sought to double down on this recognition, in fact. Yet the modern histories of both Saudi Arabia and Iran show that the application of excessive zeal can produce profoundly deleterious results.

After the failure of the Arab Spring uprisings and the reinvigorating of religious extremism and authoritarianism in the Middle East, America’s options for favorable transformations in the region are limited. The breathless accounts of Washington’s commentariat, fresh from their first encounters with the new Saudi crown prince, cannot rosy up the quality of the choices before us. The US should never bet the farm on undemocratic partners. Abandoning our commitment to religious freedom, freedom of conscience, human rights, and democracy in Saudi Arabia as a price for our special relationship with the kingdom would be a mistake. In his pronouncements on women, religious extremism, Israel, and other topics, Bin Salman has shown unexpected iconoclasm. The structural constraints he faces are enormous, however, making it prudent for the United States to exercise caution before handing the young prince a spare key to our kingdom.