- State & Local

- California

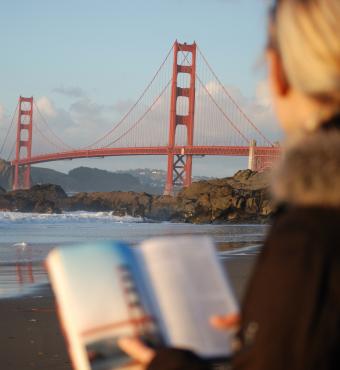

Granted, it’s awfully late in the season to be talking about summertime reading, but a recent listing of California-centric books raises the question of how best to process the Golden State.

What set this question in motion: a recent New York Times “California Today” —it’s a morning update for readers interested in the Golden State—with the alluring headline “The Books That Explain California.” (The Times’ teaser: “The nation’s most populous state is a vast and complex place. Fiction and nonfiction suggested by readers can help makes sense of it.”)

The good news: John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath made the cut—no California list would be complete without Steinbeck’s tale of Dust Bowl migrants forced west to America’s promised land.

Now, the bad news: what the “Grey Lady’s” literati (and readers) deliver is—quelle surprise!—California through a decidedly progressive lens.

For example, there’s Miracle Country, a memoir penned by Kendra Atleework recalling how she grew up in the Owens Valley of the Eastern Sierra Nevada. It’s also a sermon on the perils of climate change. As Atleework writes, “When the floods and fires begin to overpower infrastructure and disaster-response resources, when the world turns strange, when we look around for a figure to lambaste on yard signs, who, besides ourselves, will we find?”

And there’s Susan Straight’s Mecca, about life in Coachella Valley (in California, a stretch of land that represents a confluence of agriculture, hipster music festivals, and some of Barack Obama’s favorite golf courses). Among the characters in Straight’s novel: an undocumented Mexican woman who divides her time between Mecca and Los Angeles hoping to avoid deportation back to her native land.

Of course, beauty—and taste in literature—lies in the eye of the beholder. And were a right-of-center publication to engage in the same exercise, perhaps a different set of books would appear. Two that come to mind: Bad City, a nonfictional account of corruption and betrayal in Los Angeles’s more elite circles (the downfall of the dean of the University of Southern California’s prestigious Keck School of Medicine being the catalyst); and Michael Shellenberger’s San Fransicko (the book’s subtitle—“Why Progressives Ruin Cities”—is something of a plot spoiler). While we’re at it, I’ll add a third must-read: Mexifornia, by Hoover’s own Victor Davis Hanson, first published 20 years ago but still a prescient look at rural California’s transformation (here’s Victor explaining the book’s premise).

So what else to read, if one longed to learn more about California?

We’ll get to that in a moment, but first a note of caution: try to avoid those remembrances and entreaties that are too laden in nostalgia. It’s a bad tendency for many a California politician to rely too much on California’s gilded reputation and storied past so as to distract voters from the more troubled present.

Or, even worse, the temptation to evoke an abstract California that isn’t as luminous as some politicians would have you believe.

One of the chief offenders on that count: governor Gavin Newsom. Here’s the opening passage from Newsom’s second inaugural address, delivered on the seventh day of this year:

The story of our state is the story of a dream—one that has drawn strivers and seekers here forever. It’s what brought my family to California three generations ago—the promise not just of a better life but a bigger one, with opportunities they couldn’t find anywhere else in the world.

So deep does the California Dream run in the history and character of our state that it can feel as enduring as our primeval forests or our majestic mountains. But there is nothing inevitable about it. Every dream depends on the dreamers.

Setting aside the word-salad emptiness of that last sentence (of course dreams depend upon dreamers), California’s elected class would do well to avoid leaning into the Golden State of the past.

Just ask a fictional Californian: Steve Douglas.

For those unlike yours truly who didn’t grow up on California-based television sitcoms, Steve Douglas is the lead role in My Three Sons, for 12 seasons, beginning in 1960, the tale of a widower trying to manage work and a chaotic, phallocentric home (three boys, one dog, and a cranky father-in-law; plus, in later seasons, the kids’ great-uncle, doubling as a cook, maid, and male nanny).

During the show’s heyday, the Douglas family relocated from fictional Bryant Park to North Hollywood, which made sense, as Douglas was an aerospace engineer in an industry that employed an estimated 200,000 workers across the greater Los Angeles region (at the apex of the Cold War, 15 of America’s 25 largest aerospace companies were based in Southern California).

Nearly 60 years ago, Douglas and his brood could live comfortably in their new North Hollywood digs. But could they do so in today’s California? According to the website GoBanking.com, the Douglas clan would need at least $180,000 a year to “live comfortably” in Los Angeles while also paying off a mortgage (he’d actually need more, as we’ll see in a moment).

One also imagines it would have to be a generously sized residence to house the father, three sons, and the live-in relative handling domestic chores (good luck finding a family-friendly, four-bedroom home in North Hollywood with a listing price of under seven figures).

If Steve Douglas discovered that he couldn’t house his three sons in California? In 2023, he wouldn’t be alone, as approximately five out of six Californians cannot afford to buy a median-priced home.

The math behind that startling claim, per the California Association of Realtors: given California’s median price of $830,000 for an existing single-family home, buyers would need an income of $208,000 to qualify for a 30-year mortgage. (According to United Ways of California’s calculations of real-world poverty, over one-third of the Golden State’s families can’t meet their basic living costs.)

And that leads us to a fixture of today’s California that was more of a novelty in the fabled Golden State of the 1960s: Medi-Cal, the state’s version of Medicaid.

In 1966, the year Medi-Cal was first enacted (and a year before the fictional Douglas family move west), fewer than two million Californians—at the time, roughly 1.2 million recipients, constituting 6% of the state’s population—were enrolled in the program that provides free healthcare coverage to low-income residents. This past spring, California’s Medi-Cal population stood at 15.4 million enrollees—roughly 40% of California’s population.

We could go on with statistical or anecdotal tales of California’s change over the past several decades. For example, Wallace Stegner’s The Most Beautiful Place on Earth revisits how Northern California’s “Valley of Heart’s Delight” transitioned to what we now know as Silicon Valley.

But the most important statistic to remember may be this one: population change. In 1967, the year of the Douglas family’s arrival in California, the Golden State’s population for the first time cleared 19 million residents. Today’s California population is a shade north of 39 million, but for the last two years, the state has experienced a population loss. Which suggests that the vaunted “dream” of ambitious politicians is more of a nightmare to those Californians hard-pressed to make economic ends meet. (From 2015 to 2022, per Zillow, the average price of a home in California has nearly doubled, which does not make for a buyer’s market.)

So back to the question of what California books to read in what remains of this summer: look for a historian who stays on the straight and narrow.

My recommendation: the works of the late Kevin Starr, a fourth-generation Californian and former state librarian who traced his roots back to the fabled Gold Rush. (Back when I worked as a gubernatorial speechwriter, one of the more enjoyable parts of the job was tapping into Mr. Starr’s formidable imagination for State of the State themes and historical parallels.)

Starr’s first attempt at Golden State history, Americans and the California Dream, 1850–1915, first appeared 50 years ago. A dozen years later, Starr produced Inventing the Dream: California through the Progressive Era. Five years after that: Material Dreams: Southern California though the 1920s. And years later, Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990–2003, which took readers through the last decade of the 20th century.

In all, Kevin Starr wrote seven books and devoted more than one million words to the Golden State in his America and the California Dream chronology. His discovery at the end of the endeavor: “The more I investigate California, the more American it seems. It’s an intensification of the American experience, and it’s also the American experience in common. California was made up of Northerners, Southerners, Midwesterners; it incorporates all those different dimensions.”

There you have it: dimensions, not dreams.

In other words, a straightforward accounting of California’s saga—if you still have time this summer to slip in some more reading.