- Economics

- Budget & Spending

- History

- Contemporary

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

On the day America commemorated the thirtieth anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s first presidential inaugural, California Governor Jerry Brown delivered a morning speech in Sacramento that was otherwise forgettable, save for one quip. “I feel like Rip Van Winkle,” said Brown, who as usual was ad-libbing.

That Brown was even in a position to speak as California’s chief executive—in 1975, he succeeded Reagan as California’s thirty-fourth governor, and returned to his old job in January after a twenty-eight-year hiatus, which is eight years longer than Rip’s supposed nap—was one of the more remarkable stories of the 2010 election, which otherwise was unkind to tenured Democrats. California’s choice of this political dynast to solve its myriad woes (Jerry’s father, Pat Brown, governed the state for eight years until Reagan defeated him in November 1966; Jerry’s sister, Kathleen, was California’s Democratic gubernatorial nominee in 1994) says oodles about the current state of the Golden State.

In a word: austerity.

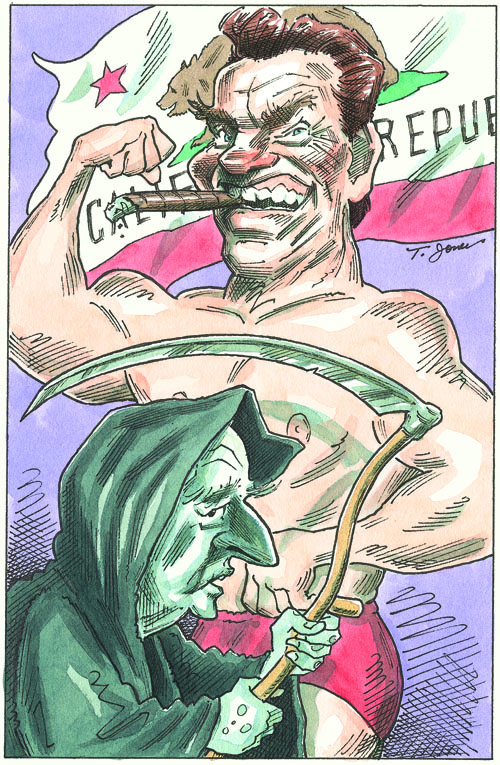

It’s what passes for life in Sacramento after Arnold Schwarzenegger who, despite his various successes and failures during his seven years as California’s governor, was always colorful. Gone are the days of the Governator’s cigar-smoking tent adjacent to his Capitol office, bombastic one-liners more befitting a movie action hero than a statesman, and his plethora of elaborately staged events (for example, setting up a video link with Tony Blair during the signing of California’s climate-change law).

In Schwarzenegger’s place: a bad-news, bad-cop governor. Awakened from his long gubernatorial nap, Brown delivered little in the way of optimism and long-term vision, and not the faintest glint of Hollywood magic. Brown’s script is the mammoth budget deficit. First he broke with tradition by eschewing a State of the State address (when your main obsession is the budget, why bother with a policy agenda?). Proving he could be a Grinch well after the holiday season, Brown seized tens of thousands of state workers’ cell phones. (During his first stint as governor, recall that Brown was known for sending frugal signals such as swapping the official limousine for a Plymouth he drove to work himself.) That was after he released a state budget that was equal parts spending cuts and tax increases, thus setting the newly returned governor on a collision course with tax-loathing Republican legislators, whose buy-in Brown needed to put his tax proposal on the ballot for a June special election. Not since Dean Wormer declared “no more fun of any kind” in Animal House, it seems, had an authority figure seemingly taken this much relish in spreading misery.

Then again, in the California of 2011, misery loves company. The Golden State continues to suffer double-digit unemployment. It will be years before California recovers the million-plus jobs lost in the recession. In Sacramento, where lawmakers must deal with a $28 billion deficit, the reality is the state’s general fund revenues won’t return to their 2007–8 level for two more years at the earliest. Even if they do find a way out of the current hole, lawmakers will be facing deficit-plagued budgets for the foreseeable future.

Brown is far from the only governor facing these dire circumstances. But what stands out is his low-octane approach, especially compared to the more dramatic strategies adopted by other newly elected governors. In New York and Wisconsin, for example, governors are at war with their states’ public-employee unions over spending cuts and pension reform. In Illinois, Democratic Governor Pat Quinn and legislators raised the personal tax rate from 3 percent to 5 percent—an act of daring or suicide, depending on one’s ideology. In Florida, Republican Rick Scott believes he can cut both spending, to solve his state’s budget, and taxes.

Meanwhile, in Sacramento, Brown chose not to brawl with the public-employees union, à la Andrew Cuomo—or any special interest, for that matter. His first instinct was to ask voters for a multiyear tax increase, the antithesis of the Illinois power play. Unlike in Florida, there was no talk of phasing out the corporate income tax to boost job creation. California, supposedly the origin of cutting-edge thought and grand political trends (a notion going back to the tax-limiting Proposition 13 and the rise of the Reagan revolution, an epoch during which Brown was governor the first time), didn’t seem to have anything all that exciting on the table.

Why would this be? Here are two explanations—aside from the fact that the state took a timeout from electing a former Mr. Universe.

First, California’s leadership is, shall we say, dated. Democrats rule the roost; for the second time in less than a decade, not a single Republican holds a statewide constitutional office. Of the nation-state’s four most influential Democrats—Brown, Senators Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi—all are septuagenarians, having emerged on the California scene four decades ago or longer (Brown’s first statewide win came in 1970, the same year Reagan ran for a second gubernatorial term). As such, they’re hardly fonts of cutting-edge political thought—or action heroes. No other state’s political ruling class is as gray, a terrific irony for youth-worshiping California. Moreover, that ruling class is also a permanent class. Last fall, amid a national wave of anti-incumbency, not a single incumbent California legislator lost his or her job.

Then again, a low political ceiling may work to Brown’s advantage. At seventy-three and in no way representative of a new political movement, Brown is hardly in a position to meddle in presidential politics. That’s a rarity among California governors, who tend to contract “Potomac fever”—Brown himself being the worst offender, having mounted quixotic presidential campaigns in 1976 and 1980 (even Schwarzenegger caught the national bug; though foreign-born and constitutionally barred from national office, he waded into debates over the future of the Republican Party and the rise of an independent movement). Brown might also decline to seek a second term in 2014, something California’s younger, ambitious, and decidedly more progressive Democrats eagerly anticipate.

This makes Brown an odd political hybrid: both a political lame duck and, at least in theory, an honest broker without ulterior motives who still emits an aura of fiscal conservatism. What better messenger to sell Californians on the concept of tough budget love?

That is, if Californians are willing to listen.

And that leads us to California’s second problem: an electorate that’s lost faith in those it elects. Consider the fate of two measures on the California ballot last November: Propositions 19 and 21. The former advocated the legalization of recreational marijuana use (an idea also on the ballot in 1970, alongside Jerry Brown and Ronald Reagan); the latter would have increased vehicle license fees to keep state parks in working order. The disparate initiatives had a common theme: the promise of more revenue for Sacramento. Yet both were soundly defeated, not the result one would expect from a state tilting left of center in its choice of officeholders. In fact, the one initiative on fall’s slate that did the most for Sacramento’s ruling class—Proposition 25, which allowed a state budget to pass with a simple majority instead of two-thirds—succeeded. That initiative, however, was sold to Californians as a way of punishing lawmakers by taking away their per diem expenses if the budget wasn’t passed on time.

Such is the current state of California politics: austere and contrarian. The Golden State’s future, for the next four years at least, rests in the hands of a career politician with four decades of experience but little to offer in the way of hope and vision. Surviving the present ordeal, as Brown has asked, requires California’s left to give ground on its precious public safety net and the right to yield on its core aversion to higher taxation.

Jerry Brown is not new. Neither is his approach. But the idea of a minus-one (spending cuts) plus another minus-one (higher taxes) leading to a political net plus? Call it the “new math” in the Golden State.