Background

In the second decade of the 21st Century, the State of Israel is still engaged in the early stages of building political sovereignty for the Jewish people, for the first time in seventy generations. The discussion of contemporary Israel is based on this historical context, the absence of a tradition of responsibility for political sovereignty.

At the end of the 20th Century, the first 50 years of Jewish statehood in Israel came to a close, and the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995, marked an ominous start to the second half-century of Israel’s modern existence. Over the course of Israel’s first fifty years, the momentum of Zionism, the Jewish national liberation movement, led to achievements that were unprecedented by any measure. All of these exceptional achievements were in the field of “hardware”—that is, the formal functions of the state. Formal procedures for state institutions were established, including elections, institutions, and agencies in each and every branch of the government. A powerful military and a thriving economy were built. On the other hand, the “operating software”—the guidelines that accommodate human diversity and enable co-existence in the civilian collective—is riddled with weaknesses.

The yawning gap between the “hardware” achievements and the “software” challenges lies at the heart of my discussion. Seven assumptions form the basis for understanding the sources and reasons for this gap; these assumptions also served as the foundation for establishing the Israel Democracy Institute as the leading “think-do” tank in Israel:

- The Jewish people lack a solid and orderly tradition of responsibility for political sovereignty.

- The Jewish people have a history of dispersion—far different from those of territorial nations with a history of sovereignty and territorial control.

- Political passivity was the most prominent characteristic of 2,000 years of exile. This passivity resulted from the convergence of Jewish religion and nationhood since time immemorial.

- The Zionist revolution to liberate the Jewish people was a secular revolution.

- The fact that Jews stood on the sidelines of the secularization process that took place over centuries in Christian countries meant that the secular Zionist revolution—which aimed to transform the course of Jewish history—developed with an inherent deficit.

- This “Zionist deficit” was the result of a secularization process that was revolutionary rather than evolutionary.

- Within the secular Zionist revolution, a religious counter-revolution emerged and continues to gain strength, threatening the future of Israel’s democracy.

The Zionist vision of bringing Jews from all corners of the earth to Zion, the Land of Israel, where the Jewish people can realize its right to self-determination, was achieved to an impressive extent. The State of Israel is a state of immigrants. In 2018, about 75 percent of its 8,950,000 citizens were Jews, and among them about 70 percent were native born, or second- or third-generation to immigrant parents. Since the founding of the State of Israel, and in particular in recent decades, Israeli society and its political culture have changed at an unprecedented pace. These changes have entailed far-reaching and dynamic developments, including in its normative foundations. They have brought demographic changes and have widened economic disparity between the haves and have-nots. Above all else, Israel has undergone constant transformations in its political culture and conduct, which have been characterized by polarization and increasing extremism.

These dynamic changes are unique in comparison to other countries. For example, Israel’s population numbered about 3.3 million people at the time of the Yom Kippur War (1973). When the war started, about 53 percent of Israeli Jews were immigrants and most of the others were children of immigrants. By the middle of the second decade of the 21st Century, the population had soared to over 8.5 million. This is an enormous demographic change, and it has had a major effect on all of the aspects noted above, including the socio-economic and cultural characteristics of Israel.

Israeli society is a multi-colored mosaic. It is rich, diverse—and deeply disharmonious. It is made up of a collection of heterogeneous minorities—Arab, religious Zionist, ultra-Orthodox, new immigrants, secular Jews, Ashkenazi, and Sephardi. None of these minorities are monolithic and their members run the full gamut of the political spectrum, creating a sort of disharmony that can sometimes be jarring. This mosaic—or “map of tribes” as President Reuven Rivlin termed it—is not static. As a diverse society, Israel is a patchwork of diversity.

To gain a better understanding of the vulnerabilities of Israel’s democracy and the challenges to its social cohesion, it is important to recognize the fact that the State of Israel lacks a constitution to bind the workings of its democracy and a bill of rights to safeguard the freedoms of its citizens and underpin the norms of its civil society. Instead, Israel has a compilation of “Basic Laws” designed to serve as a provisional constitutional framework.

The lack of a constitution has existential and far-reaching repercussions. Unlike more substantive and developed democracies, Israel lacks the consensual underpinnings that stabilize governance and enable the inclusion of diverse views, outlooks, and beliefs. The decision to formulate a constitution for Israel was cited in the state’s Declaration of Independence on May 15, 1948: “We declare that, with effect from the moment of the termination of the [British] Mandate … [and] until the establishment of the elected, regular authorities of the State in accordance with the Constitution which shall be adopted by the Elected Constituent Assembly not later than the 1st October 1948, the People’s Council shall act as a Provisional Council of State.”

The first Israel elections were held in January 1949 to elect representatives to a national assembly that was slated to produce a constitution by October of that year. The opportunity was missed because David Ben-Gurion was unwilling. Why? What reason did the founding father of the State of Israel have for opposing a written constitution? Given that the Jews had lacked a national territory and common language for so long—seventy generations—Israel’s founding father was not certain that the nascent Jewish state would survive. (Until 1939, he never even spoke of statehood.) Ben-Gurion’s great wish was to build a nation out of the multicultural, multilingual Jewish people scattered around the globe and to guarantee its independence and sovereignty. The tasks ahead were vast, and a constitution, Ben-Gurion apparently believed, would tie his hands. Given the enormity of other challenges, and despite an abundance of intellect and savvy, the all-important political will was missing, and so was a constitution.

Israeli Society: Diversity, Integration, and Divisiveness—A Descriptive Perspective

At the end of 2018, approximately nine million people lived in Israel: 74.3 percent Jews, 20.4 percent Arabs, and 4.8 percent others. Among the non-Jewish population, about 83 percent are Muslims, 9 percent are Christians, and 8 percent are Druze. As noted, Israeli society is very diverse. The dynamic changes in Israeli society since the state’s establishment are particularly evident among the Jewish majority, and the salient parameter that divides this majority is religious identity—that is, the extent of religiousness. About 55 percent of Israeli Jews define themselves as secular, 26 percent as traditional,1 10 percent as national-religious (Orthodox), and 9 percent as ultra-Orthodox.

One way to illustrate this dynamic is to compare the lifestyles of four Israeli men in their early twenties.

The ultra-Orthodox man most likely does not serve in the Israeli army—meaning he is bereft of any connection with one of the central cultural institutions in Israel. By his early twenties he is probably already married to a woman he met in an arranged marriage, and the couple probably already has at least one child. A decade from now, he will be the father 6.5 children, according to the average for men from his sector of Israeli society.

At this age, the national-religious Jew will still be serving in the army and will have no sexual history, even if he has a girlfriend. He will most likely start a family before the age of 25, and father around 4.5 children over the next 10-15 years.

The secular Jewish man is also in the army (or has just finished his service). He has no religious or cultural restrictions that would keep him from engaging in casual sex before marriage, and his considerations for starting a family are vastly different than that of his ultra-Orthodox and national-religious counterparts. On average he will marry in his late twenties or early thirties and father 2.3 children.

In the Arab sector, it is more difficult to define a classic prototypical male. In general, however, we know that between the ages of 18-22, about 40 percent of Arab men in Israel are not employed or studying or engaging in any sort of civilian national service. Overall, the average number of children per Israeli Arab family is 2.9, and this number is declining.

The diversity and changes in the makeup of Israeli society can also be illustrated from two additional perspectives: fertility rates (demography) and participation in the workforce.

Fertility Rates

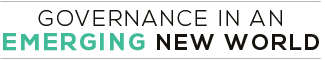

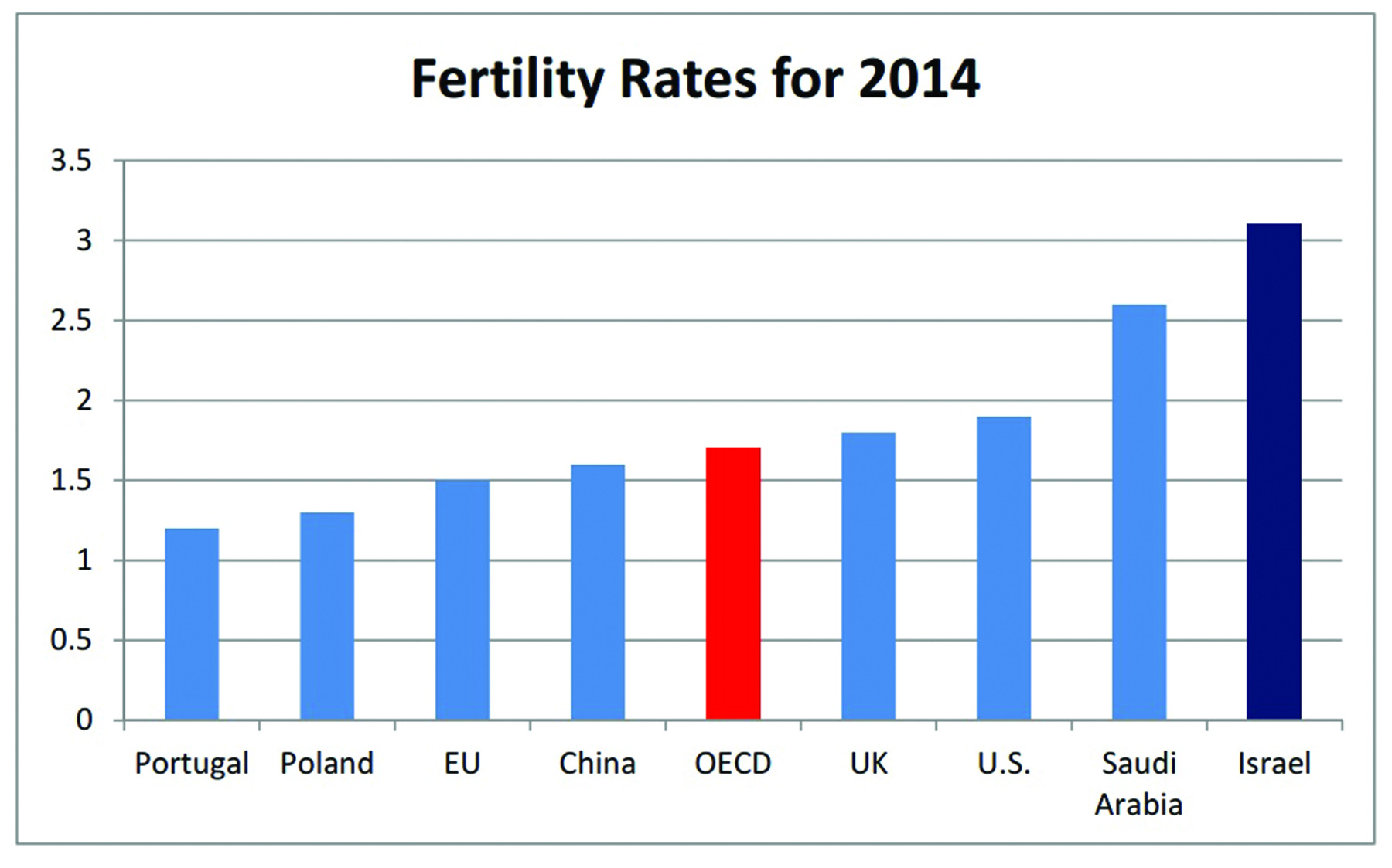

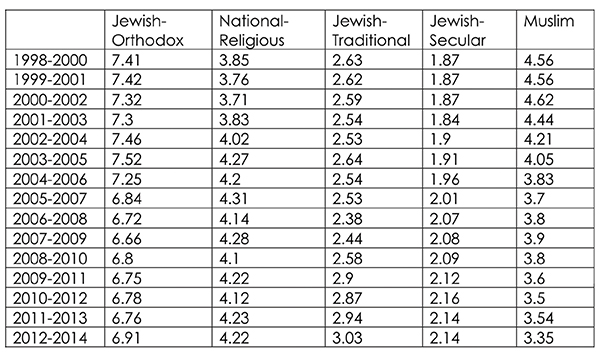

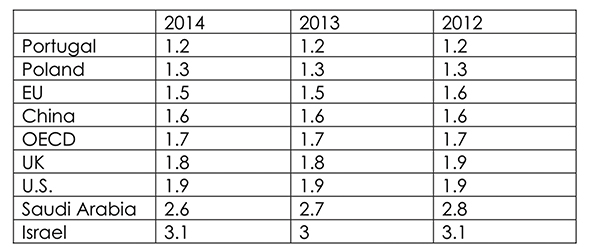

The data displayed in Figure 1 and in Table 1 yields several insights: First, over time, there was a moderate decline in the average number of children in ultra-Orthodox and Muslim families in Israel. This trend is slow, but steady. On the other hand, the average number of children in secular and religious families seems to have remained constant. And as we see in Table 2 and Figure 2, the fertility rate in Israel is high relative to other countries.

The Hardware: The Strengths of Israel’s Material Infrastructure

The data displayed will obviously have an impact on the future of the job market in Israel and on population density. A detailed discussion of the latter is beyond the scope of this paper, but here are a few notes on this issue: Israel’s population is growing at an annual pace of 2 percent, compared to an average of 0.5 percent in the OECD countries; in Israel, where about 60 percent of its territory (within the Green Line) is desert, population density is about 1,000 times higher than the OECD average.

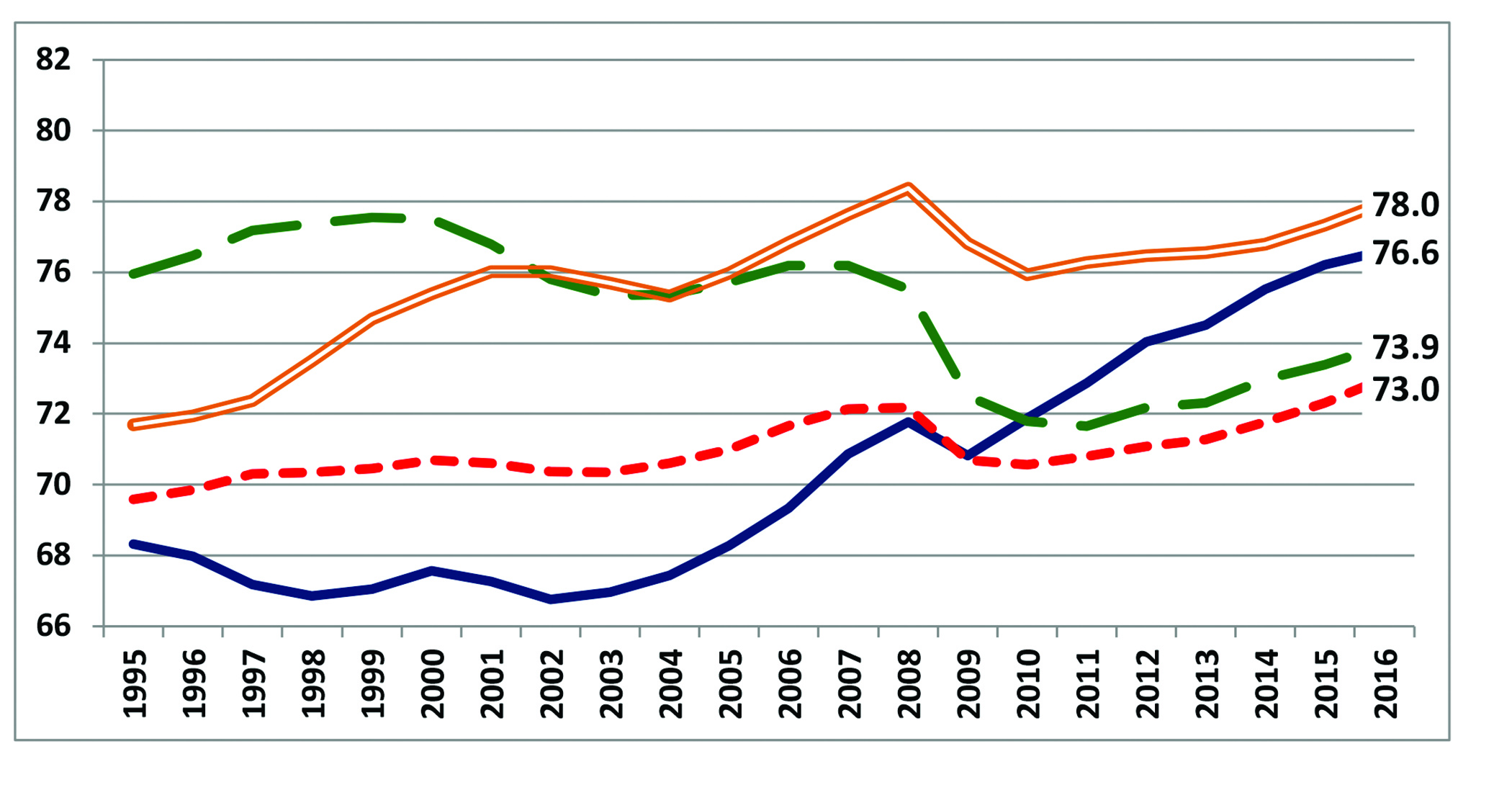

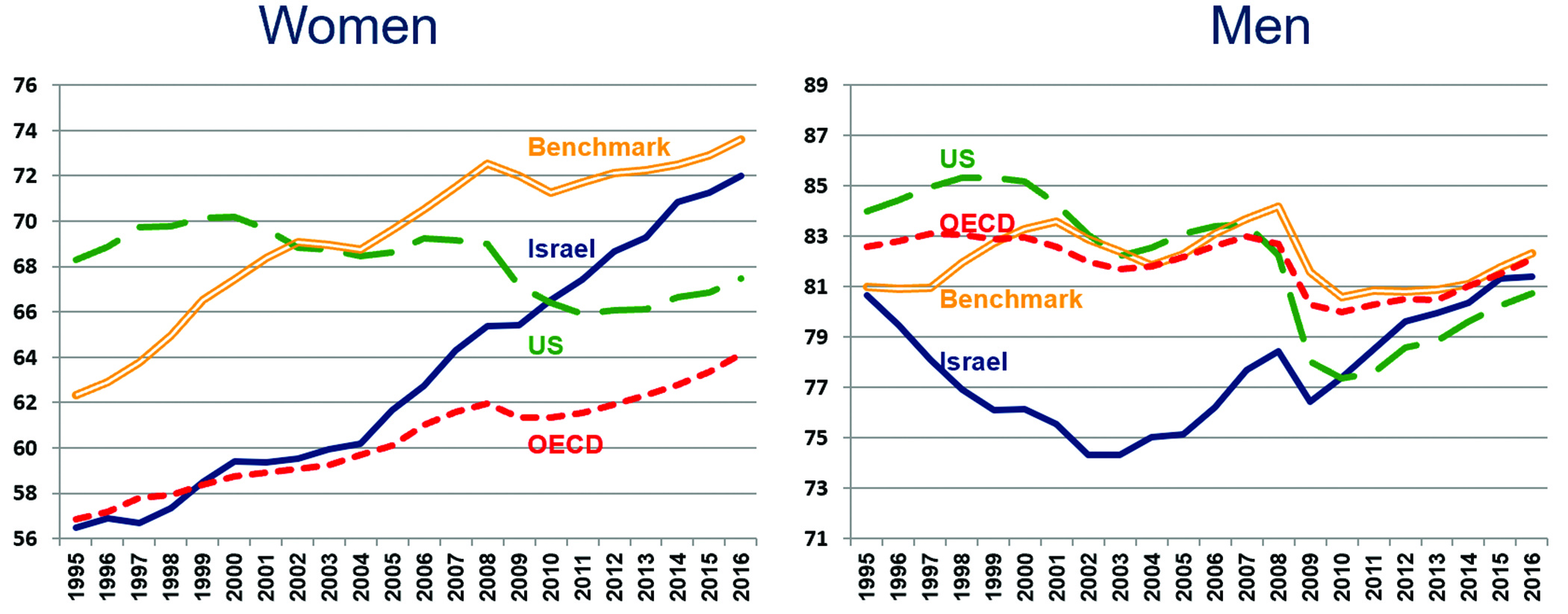

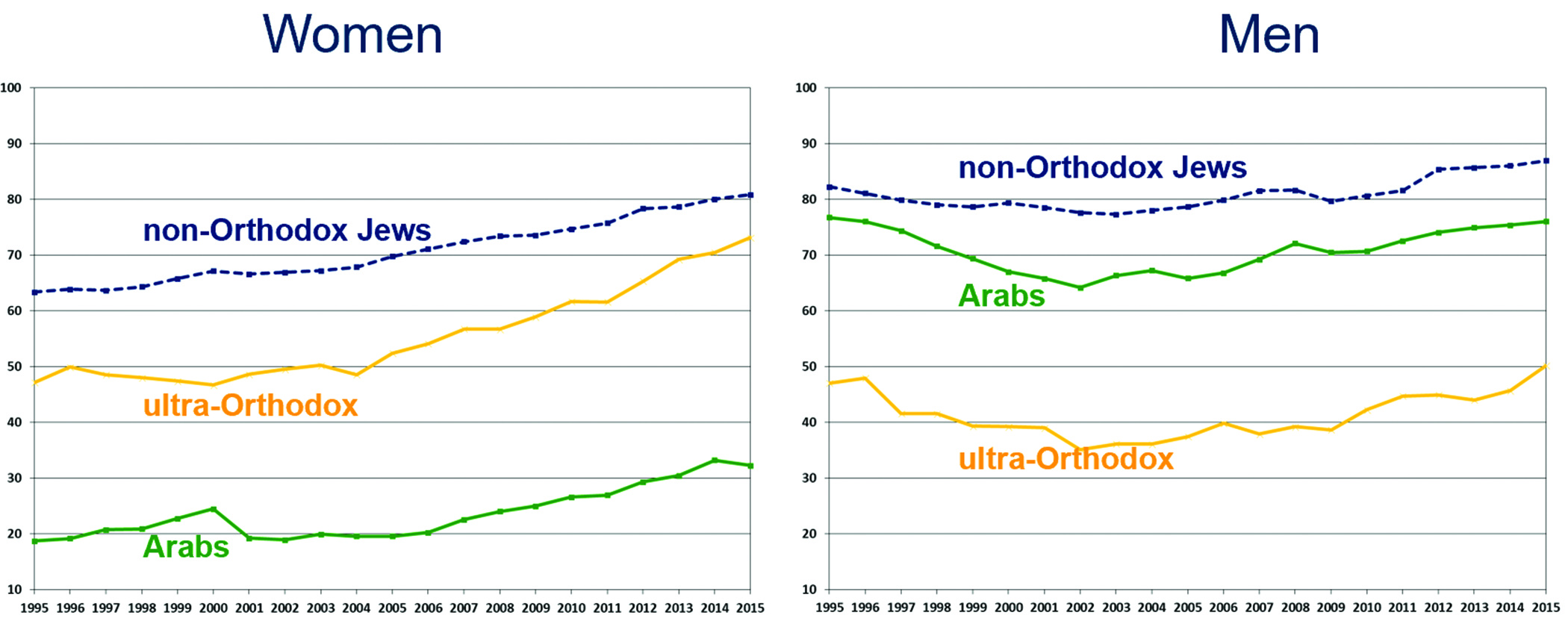

Like the data on fertility, the data on changes in the job market indicates trends of integration, however slow, of both ultra-Orthodox Jews and of Arabs into the mainstream of Israeli society. There was an impressive increase of 10 percent in the employment rate between 2001 and 2016, as shown in Figure 3. This increase stems from the growing participation of women and men in the workforce in general (Figure 4) and of ultra-Orthodox Jews and Arabs in particular (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 4, there was a reversal of the downward trend among men and an accelerated increase in the participation of women. In both cases, participation in the labor force in Israel reached the same level of participation as in the benchmark countries. Moreover, the gap between men and women narrowed and is today one of the lowest among OECD states.

Most of the increase in workforce participation between the years 2002–2015 involved Jews who are not ultra-Orthodox (an increase of 68 percent among men and 73 percent among women). However, as shown in Figure 5, there was also significant growth in workforce participation among ultra-Orthodox and Arab men and women. (The participation of ultra-Orthodox women in the workforce is similar to that of Jewish women who are not ultra-Orthodox, and a higher percentage of ultra-Orthodox women work compared to their male counterparts.)

It should also be noted that the unemployment rate in Israel in 2018 dropped to a historic low of 4 percent. The moderate decline in fertility rates in the ultra-Orthodox and Arab sectors, along with a significant increase in their participation in the job market, reflect their integration, albeit slow, into mainstream Israeli society. Evidence of this can be also be found in poverty data in Israel. In 2017, 17.9 percent of the population lived under the poverty line. (The OECD average that year was 11.8 percent.) This high percentage is attributable in part to the two minority groups mentioned: 47.1 percent of the Arab citizens of Israel were under the poverty line in 2017 (down from 52.6 percent in 2014) and 43.1 percent of ultra-Orthodox lived in poverty (compared to 54.3 percent in 2014). (See supporting data).

All of this data underlines the potential of integration. There is no doubt that the technological revolution in its various forms has reinforced the trends of integration. We’ll later discuss the impact of this revolution, including its role in widening disparities and rifts.

The Economy—The Pillar of the “Hardware”

In general, we can say that the Israeli economy illustrates the “upside” in the depiction of Israeli society’s complexities. The population has grown almost twelvefold since the state was created, and its physical infrastructure has grown accordingly. Some 46 percent of Israelis have higher education, second only to Canada (51 percent) and ahead of the Japan (45 percent) and the U.S. (42 percent). (It should be noted that the 1961 census found that 250,000 adult Jews in Israel ages 14 and above—about 15 percent of Israel’s Jewish population at the time—could not read or write in any language.) Similarly, the strength, capabilities and resilience of the defense establishment have steadily grown. These are some of the signs of the unprecedented transformation from a reality of multiple Diaspora communities to frameworks that contain the physical-material foundations of political sovereignty.

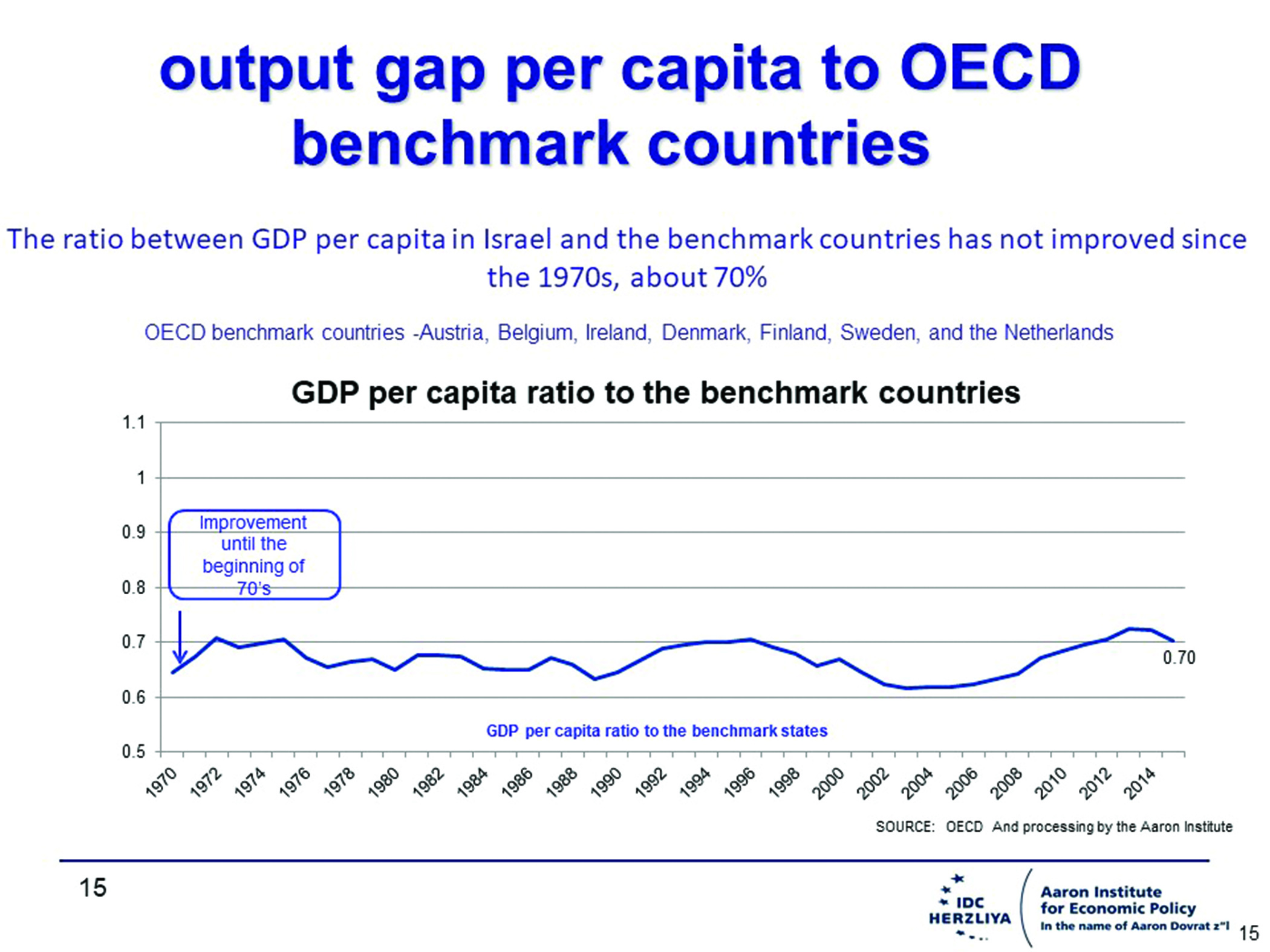

The salient characteristic of Israeli society is its stability over time. Figure 6 shows the stability of the gap between GDP per capita in Israel versus the benchmark countries since 1970. According to IMF data, GDP per capita in Israel stood at $36,250 in 2017, placing Israel 35th in the world in this metric and at a level equal to 70 percent of the GDP per capita in the benchmark countries. (On the other hand, Israel’s economic output far surpasses that of neighboring states: In Jordan, per capita GDP was $12,487 in 2017, or 94th in the global ranking; Egypt—$12,995, 92nd place; Iran—$20,030, 64th place; and Saudi Arabia - $55,263, 12th place.)

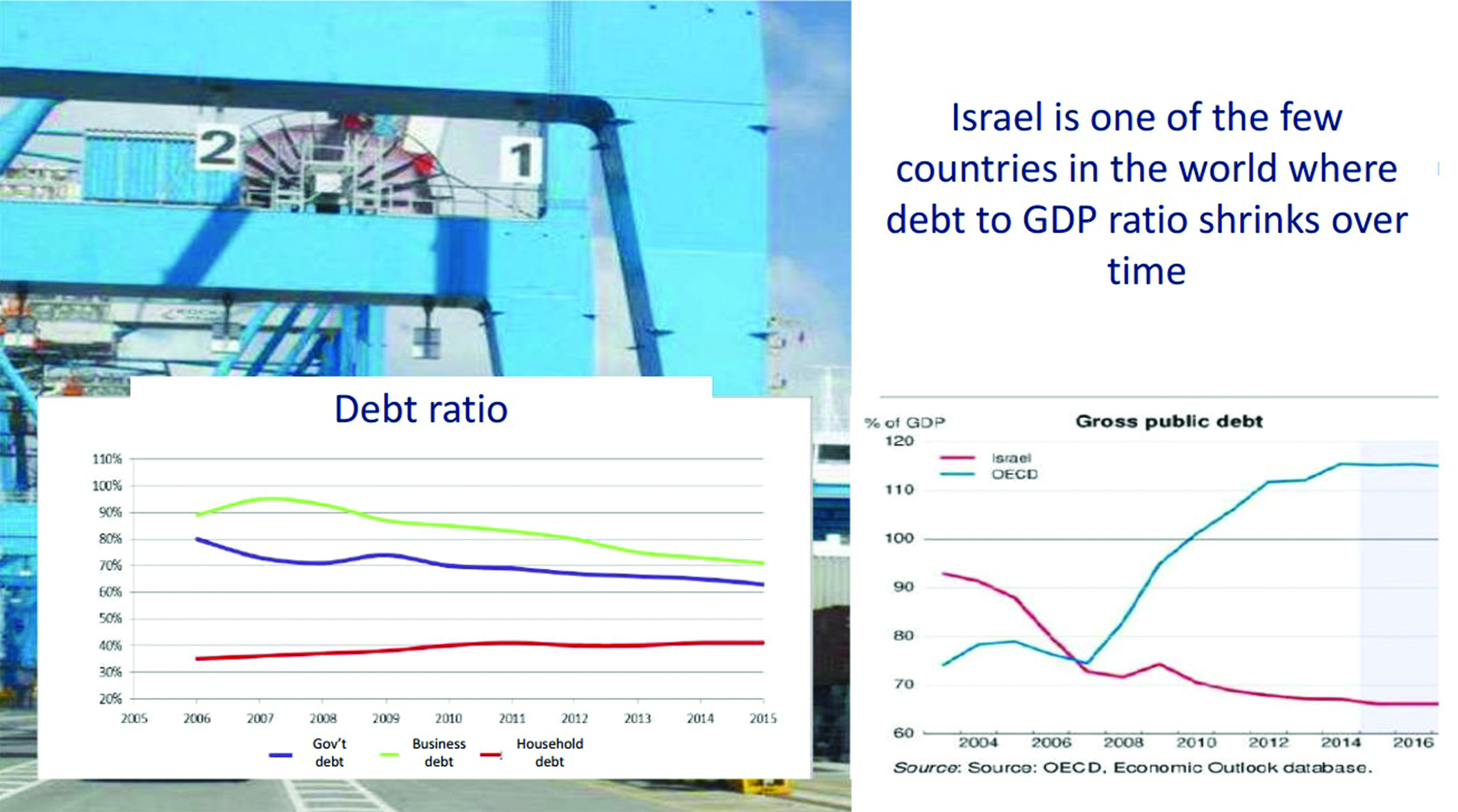

The stability of the Israeli economy is also evident when measuring the debt to GDP ratio (Figure 7). The turning point occurred in 1985 with the implementation of the Economic Stabilization Plan, promoted by then-Secretary of State George Shultz. Since 1985, Israel has maintained a sound economic program characterized by responsible fiscal conduct.

We’ll now take a close look at the high-tech industry in Israel but must first emphasize that there is actually a dual economy in Israel. The high-tech industry accounts for about 10 percent of the labor force and 35 percent of Israel’s exports. On the other hand, Israel’s “other” economy, which constitutes 90 percent of the workforce, is plagued by low productivity. The governor of the Bank of Israel, Karnit Flug, noted last year that “work productivity in Israel is lower than in most OECD states and we are finding it difficult to close the gap.” According to Flug, this situation is attributable to the business environment and excessive regulation. “Starting a business in Israel is very difficult and even complicated,” she said.

Workers in the high-tech sector are usually at a higher level on the socio-economic scale, while the “other” economy is primarily comprised of residents from the geographic and cultural-ethnic periphery (ultra-Orthodox Jews and Arabs). Flug also noted another significant weakness of the labor force in Israel: the population’s level of skills compared to other OECD countries. In tests of basic skills, Israel almost always lags behind other developed countries. However, as Flug also noted, “the percentage of people with post-secondary education in Israel is particularly high, largely thanks to the immigration from Russia, which boosted the high-tech sector in particular.” The governor spoke favorably about the well-developed venture capital industry. “The number of Israeli companies registered on Nasdaq is second only to the U.S. and Canada. Over 300 companies operate R&D centers in Israel, and there are more than 5,000 startups, including about 300 in the cyber field.”

Flug also noted the decline in unemployment in Israel, which now stands at 4 percent among Israelis of working age; in comparison, unemployment is 10 percent in Europe. “This low unemployment rate is despite a high pace of [additional workers] joining the job market,” she emphasized. According to Flug, the rapid increase in real wages—in both the business and public sectors—is another indication of the strength of the labor market. “Wages rose by 3.5 percent in the business sector last year, which leads to a rise in the standard of living. In some sectors, we are even starting to see a shortage of workers, which limits the ability to continue to grow.”

‘Exit Nation’

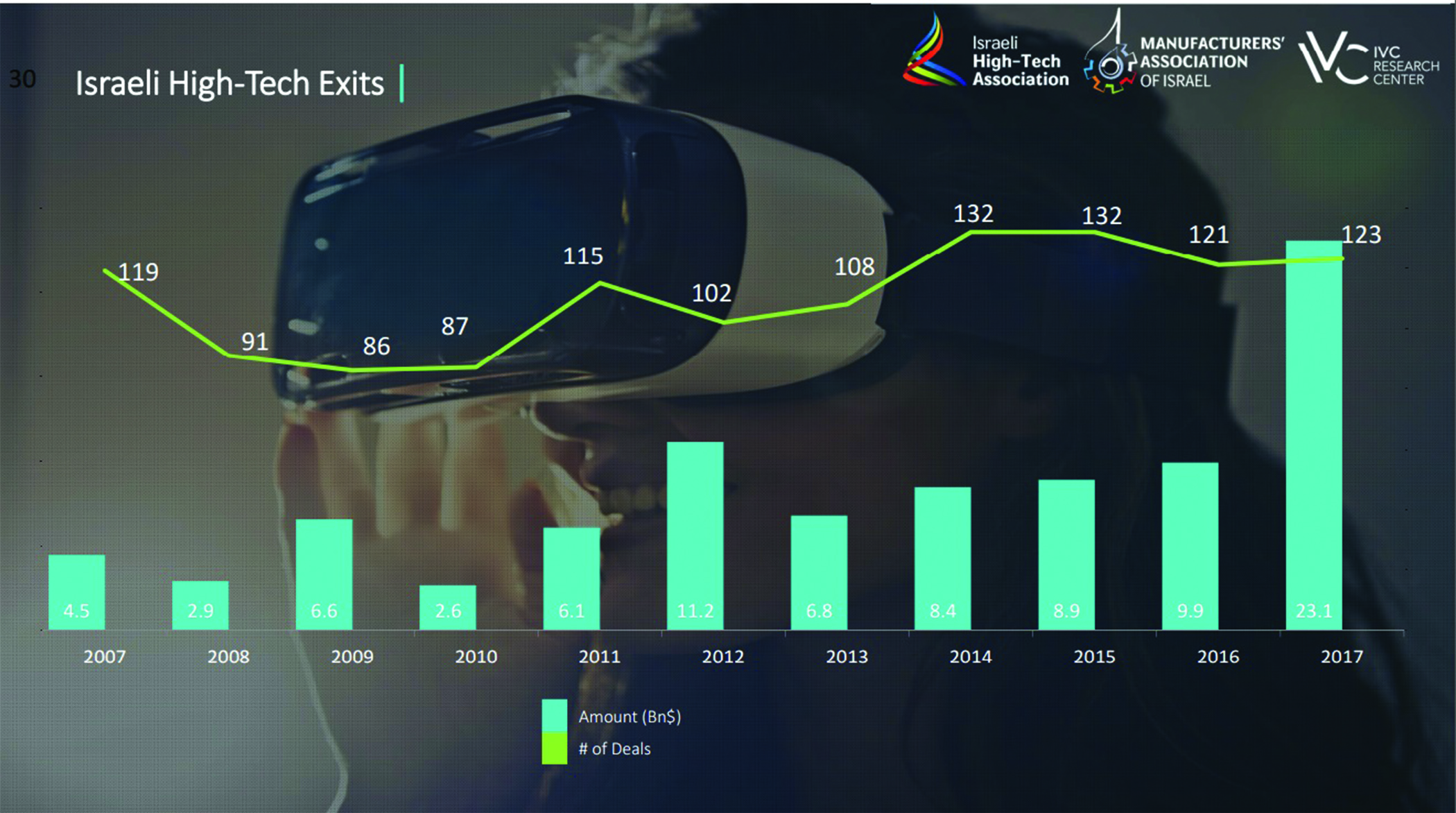

Israeli high-tech is one of the unique characteristics of the Israeli economy in recent decades. Though driven by a small percentage of the workforce, some call it the “locomotive” of the economy. The feature that has made Israeli high-tech what it is today, a global trailblazer in the technology revolution, is a unique brand of Israeli innovation. Those who have studied the developments in the Israeli high-tech sector largely attribute Israeli innovation to “exceptional innovative capabilities per capita.” These are expressed in a tangible and practical way in the culture of exits that has developed in Israel. Figure 8 shows the sum of exits from 2005-2015, which earned a total of $54.11 billion.

The next three figures (9, 10, and 11) provide three perspectives on Israel’s strength in these areas: First, there are 101 Israeli companies listed on Nasdaq today. Only the United States, China, and Canada have a larger Nasdaq presence. Secondly, about 365 global giants have established R&D centers in Israel—including Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and others. Thirdly, Israel ranks second in investment confidence in venture capital.

The reality described above—of extraordinary achievement that turned Israel into a global power in the high-tech sector—is not the product of strategic planning. Policymakers never sketched the vision of Exit Nation. This reality, in a state nearly identical in size and population to New Jersey, evolved amidst a cluster of constraints—including the needs of physical security. The need for a functional response to tangible threats to physical existence explains, in retrospect, the focus on research and the flourishing development of innovations that find their way to global markets. An additional constraint was already mentioned—the small size of the state and its population. The result is a disproportionate presence in global markets. Indeed, every smartphone in the world contains a number of components developed by Israelis.

As noted, this reality was not a product of strategic planning. It resulted from a combination of high-quality personnel and security needs and emerged in response to the failure of Israel’s intelligence agencies to foresee the outbreak of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, in which Israel suffered heavy casualties and faced a real existential threat. This colossal intelligence “blunder” was not the first such debacle. For example, Egypt began to move large forces across the Suez Canal on February 18, 1960, acting upon false information from Russia claiming that Israel was about to attack Syria. Within six days, the Egyptian army managed to deploy over 500 tanks on Israel’s southern border without eliciting an alert by Israeli intelligence.

Nonetheless, the failure of Israel’s military intelligence to provide a high-quality strategic warning about an imminent war in 1973 was extraordinary even in the long annals of intelligence failures in the 20th Century. This failure stands out in particular in light of the wide gap between the large quantity of warning data the army had and the low-quality warning it ultimately provided. One of the strategic lessons from the intelligence failure was that Israel needed to rapidly engage in technological intelligence R&D in order to address existing and future threats, and not to rely on the “abilities and favors of others.”

The IDF’s signal intelligence (SIGINT) and code decryption unit is known today as Unit 8200. Before the Yom Kippur War, knowledge of Arabic was the sole criterion for recruiting soldiers for the unit. After the war, a decision was made to expand the ranks of the unit and to give it priority over other units in recruiting soldiers; emphasis was placed on excellence in mathematics and innovation. Suitable recruits would be available to other units only after 8200 filled its personnel quota. At the same time, the unit’s budget increased disproportionately to its size and relative to other IDF units. The unit was also allowed considerable autonomy in defining and addressing needs. Finally, an R&D division was established within Unit 8200. Israel is unique in conducting both regular intelligence work and technological development within a single military intelligence unit.

The conceptual challenge of addressing urgent needs in a wide range of state-of-the art and future technologies gives the unit’s graduates a huge advantage vis-à-vis R&D organizations in the world. The experience of working as a team to find timely solutions, despite limited resources of personnel and money, closely simulates the world of startups. Like 8200, a startup entrepreneur must offer a solution to a complex problem for which no solution exists, and the basic assumption is that the solution will be attractive to everyone facing this problem. Consequently, many solutions that 8200 develops for its intelligence needs can later be applied in the civilian world. A prominent example is Check Point, the flagship Israeli company that for years has played a leading role in the world in developing cyber solutions. Many of these solutions, like Check Point’s founders and most of its personnel, come from Unit 8200.

Cyber Industries in Israel

The information revolution and the exponential growth in digitization and innovation have spawned cyber threats that are seen by the intelligence community in Israel as even more dangerous than unconventional weaponry. The cyber industry today accounts for a significant part of the software industry in Israel. It includes a wide range of companies engaged in developing and marketing software designed to defend against cyber warfare and cybercrimes. Some have operated as independent companies for many years, while others are startups that were sold to foreign companies and continue to operate in Israel as R&D centers for the corporations that acquired them. Work is also being done in Israel, secretly and openly, on developing offensive tools for cyber warfare.

Since the start of the 21st Century, all of the leading security companies in Israel began to work extensively in this area, including Israel Aerospace Industries, Rafael Advanced Defense Systems, Elbit, and Israel Military Industries.

As of 2017, about 400 Israeli companies worked in this field, along with about 25 multinational corporations with Israeli branches. Israel’s exports of cyber-related systems and services totals about $3 billion, including about $2.5 billion to the United States.

In 2015, the National Cyber Security Authority was established to defend the civilian cyber space, promote Israel’s capabilities in this field, and enhance methods for contending with current and future challenges in the worlds of cyber. It is also responsible for promoting Israel as a leading center for developing cyber knowledge and technologies.

Israel National Cyber Readiness Team, CERT-IL, is Israel’s focal point for cyber security incident management and is part of the National Cyber Security Authority. Its tasks include:

- National cyber security incident management

- Sharing cyber security actionable intelligence with trusted partners in Israel and around the world

- Developing cyber security methodologies and techniques

- Promoting cyber security awareness

- Providing a single point of contact in Israel regarding cyber security threats and incidents for international corporations, cyber security companies and other CERTs

Israel is considered a cyber power today. Seven Israeli cyber companies are ranked among the 100 best cyber companies in the world. About 400 high-tech companies are active in this field. It is already hard to imagine that only a few years ago cyber was an obscure concept.

Artificial intelligence (AI)

According to a position paper by the Science Ministry’s National Council for R&D, a process similar to what occurred in the cyber field is now unfolding in the field of artificial intelligence. A combination of recent scientific and engineering achievements has significantly boosted the capabilities of AI and data scientists in Israel and the world. In Israel, (as of 2018) 898 companies are defined as working on AI-related projects, including developments in medicine, autonomous vehicles, machine learning, and analysis of big data, as well as AI applications for social media, ecommerce, digital health, security and more. An analysis conducted by the Samuel Neaman Institute for National Policy Research at the Technion, at the request of the National Council for R&D, identified the number of Israeli companies working in specific areas of AI:

- 145—Social media and advertising

- 145—Software applications

- 142—Financial technology and ecommerce

- 114—Digital health and medical technologies

- 108—Software solutions for organizations

Numerous innovations have emerged in these fields in recent years, including: computerized medical advisors that give medical recommendations identical to those of human physicians in 99 percent of the cases; computerized judges capable of predicting the outcome of trials conducted by human judges; and algorithms that recommend buying specific stocks and often execute the stock purchase—a million times faster than an average person could. Even in the physical world, we’re seeing algorithms that guide autonomous vehicles on roads and that control the operation of smart homes.

During the next decade, algorithms are expected to play an increasing role in supporting our daily needs. AI-based digital experts will advise us on all possible subjects, wherever we seek their help. Articles in this field raise the following questions: How do we move toward a future like this? How do we transition from thinking that only human beings are capable of complex cognitive tasks to a daily routine of AI-generated advice, ideas, analysis, and discussion? How do we acclimate users to the new situation without causing mental turmoil? The title of one of the articles addressing these questions in the field of medicine is: “How AI is Transforming Healthcare: Diagnostics, R&D and Therapeutics”

The scope and quality of high-tech industries in Israel, which are disproportionate to its size and population, are the product of need; they combine a response to the pressures of security and the unique creative attributes of Israelis. When asked about the source of this creativity, most respondents emphasize two traits: First, the fear of failure is not a relevant consideration among the Israelis who are developing such a wide range of products. Secondly, improvisation; the expression “by the book” does not exist for them. The lack of a fear of failure and the ability to improvise are two critical traits for an army—an organization that must provide answers “in no time” to threats on various fronts in different dimensions.

The Water Industry

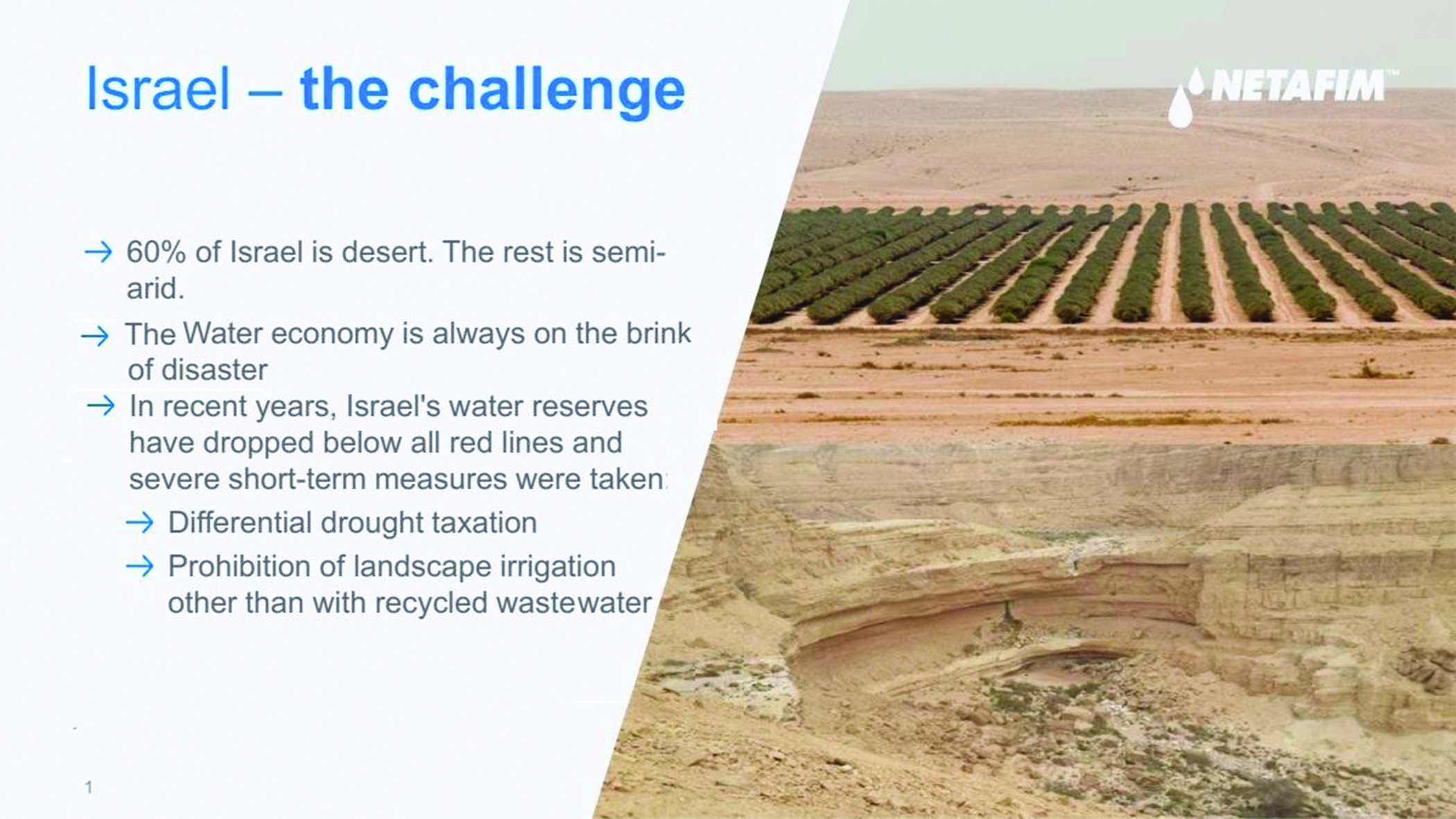

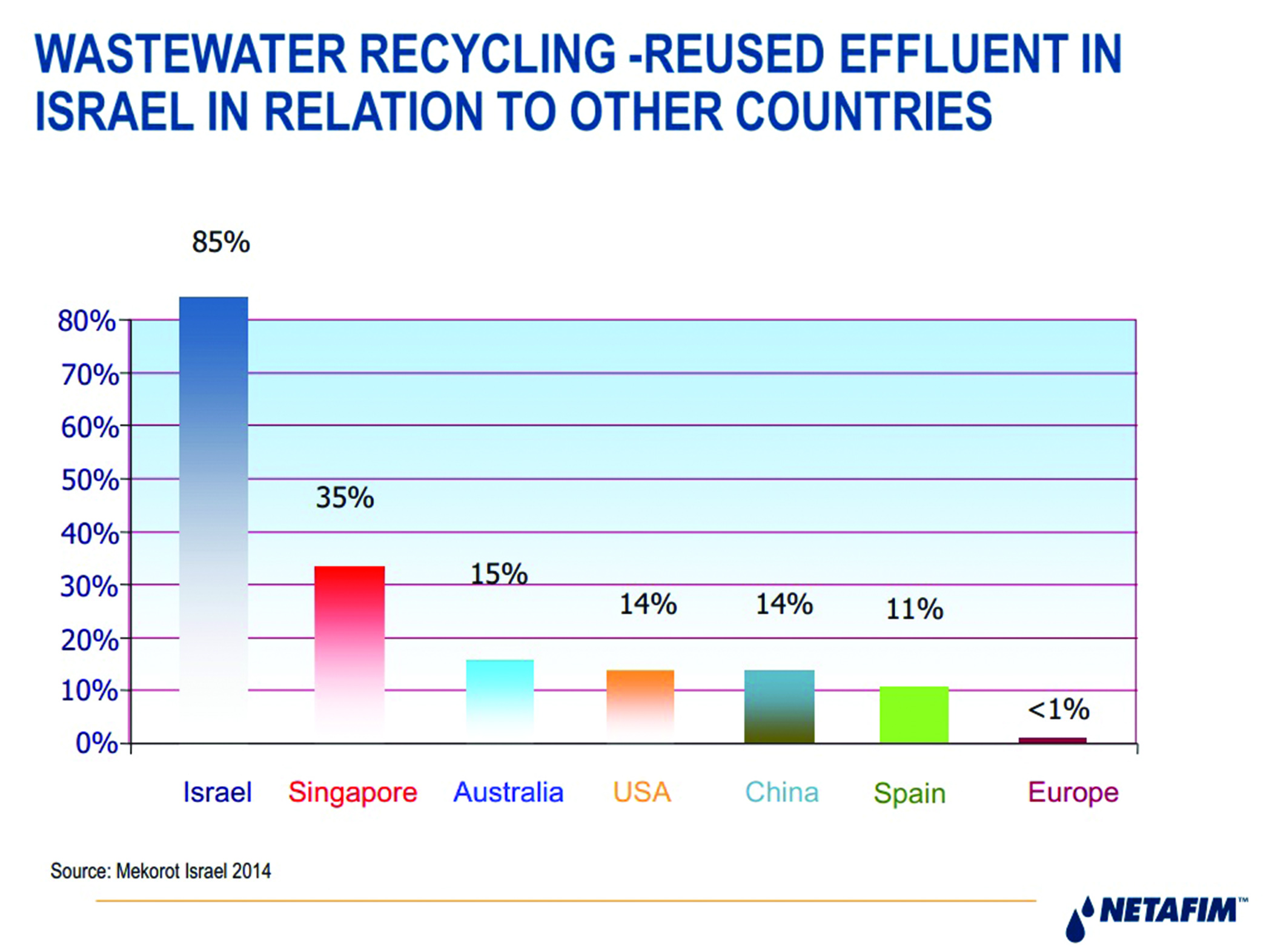

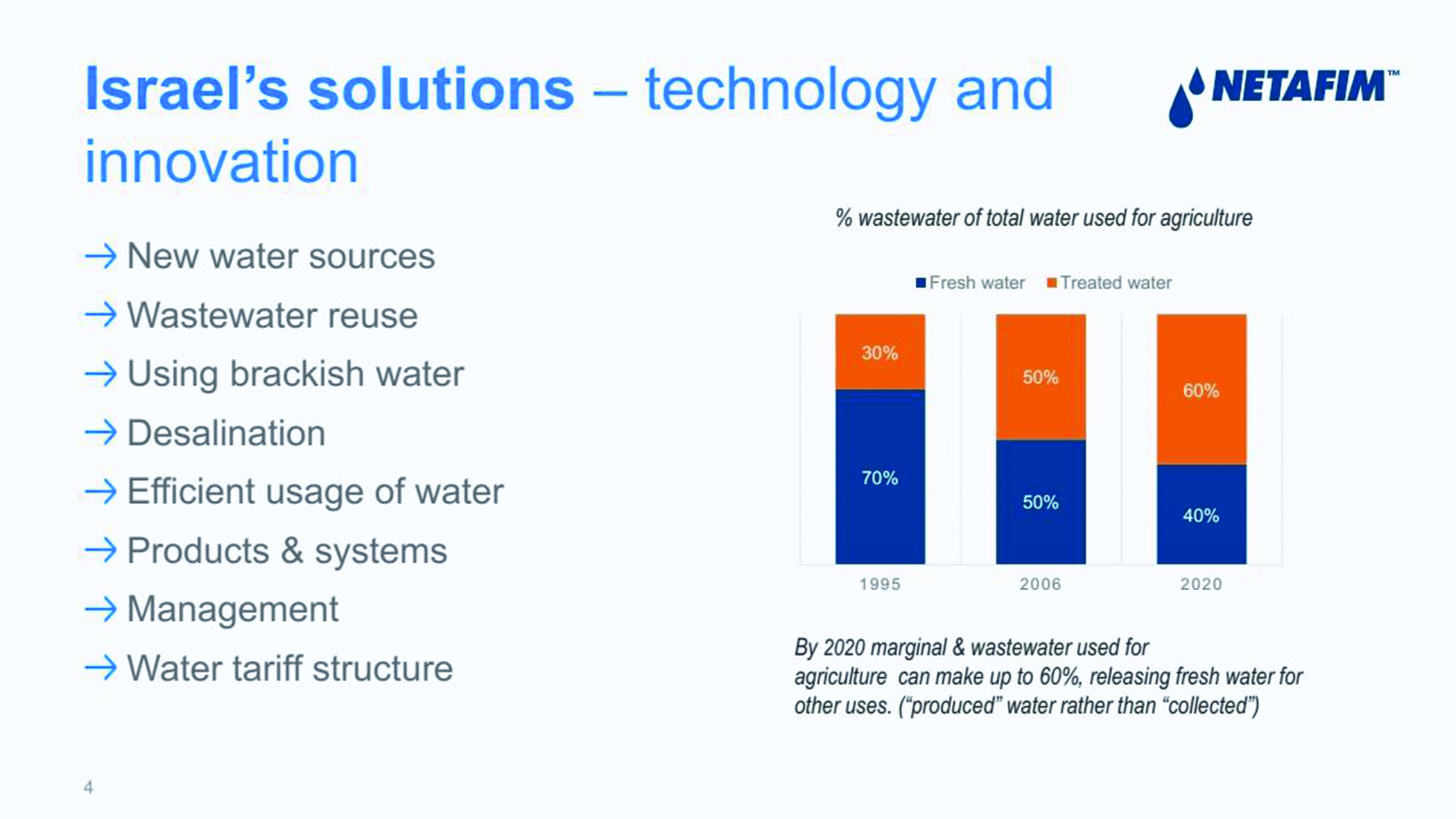

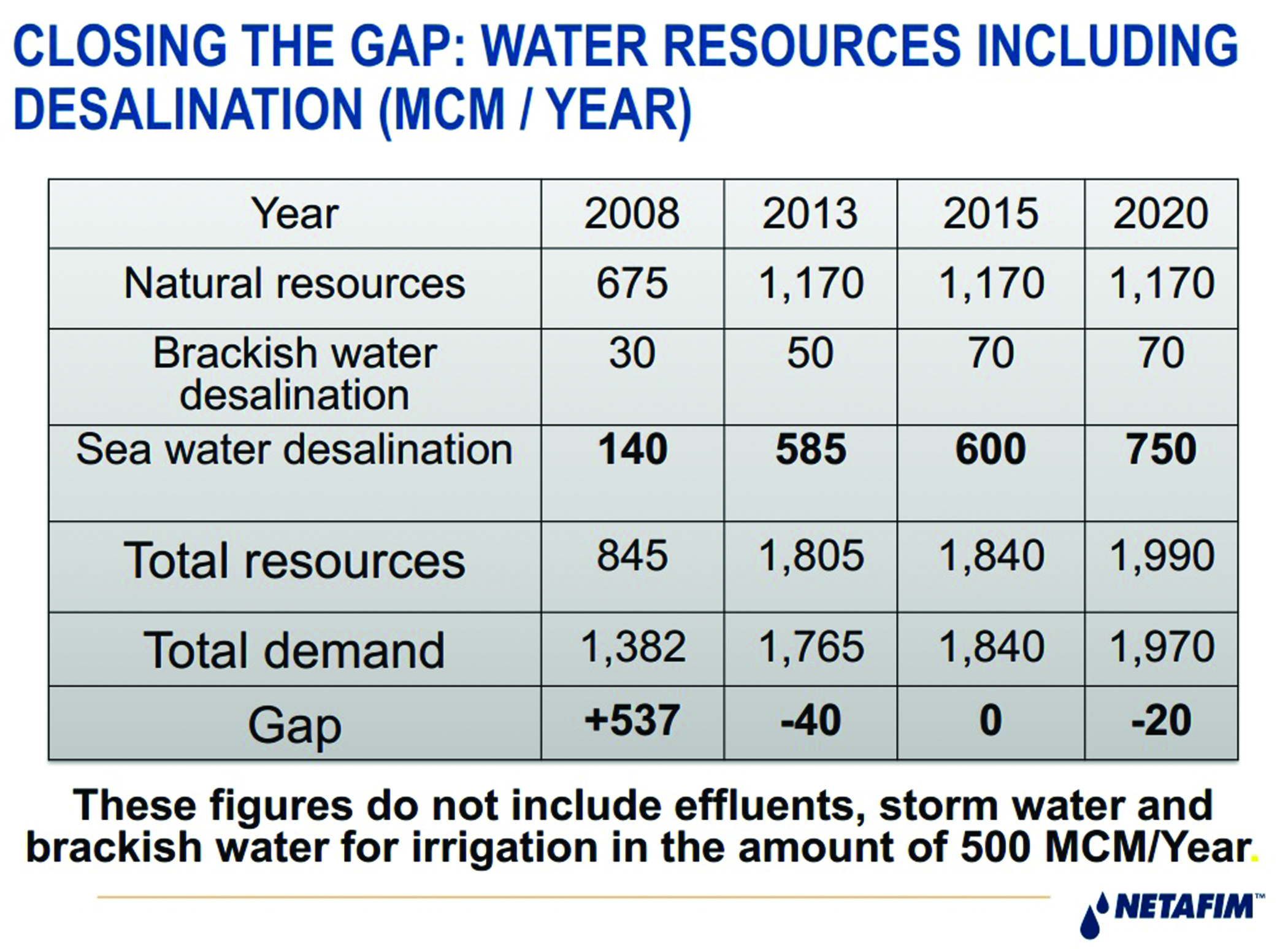

Water is another field where Israel stands at the global forefront of development. Here too, Israeli innovations were driven by need. About 60 percent of Israel’s territory is desert, and the rest of the country is semi-arid with limited natural sources of water. Nonetheless, Israel has basically solved its water problem. As shown in Figure 14, Israel’s water reserves have fallen below all of the red lines in recent years. In the Sea of Galilee, for example, the water level today is 4.3 meters below the upper line. The State of Israel has solved the water challenges through two components: recycling of waste water and desalination. Figure 16 shows the measures Israel has taken to overcome its chronic water deficit. Figures 16 and 17 describe the changes in the ratio of natural water sources to desalinated water, and Figure 15 shows the percentage of desalinated water in Israel in comparison to other countries.

In addition to developing desalination equipment and systems, Israeli creativity in the face of water needs and challenges was expressed in the development of smart irrigation—drip irrigation. This original Israeli method releases a slow drip of water to the roots of plants, whether above ground or directly to the root area under the soil (underground irrigation). Today, drip irrigation systems are produced by various companies in the world. Israel played a central role in the development and production of these systems. This invention launched a global revolution in the irrigation and fertilization of crops, conserved water, and boosted agricultural yields. Israeli companies today have a global market share of about 50 percent in the field of irrigation.

Social Media

Internet usage in Israel, including social media, is generally similar to that of other developed countries. The data I present here (in random order, not by order of importance) indicate the centrality of internet applications in Israeli culture and their impact on the views and behavior of Israelis. The data are from a 2017 report by Bezeq.21

In 2017, there were 6.6 million internet users in Israel—more than 75 percent of the population, including 91.5 percent of Jews, 84.5 percent of Arabs, and 44.5 percent of ultra-Orthodox Jews.

The average broadband for landline internet continues to increase with the rise in internet use; the average internet package today offers a download speed of about 6.7 megabytes per second. Some 36 percent of Israelis use streaming services and software, and 15 percent reside in smart homes. More and more Israelis are using cloud services: 67 percent use cloud technology to back up pictures, videos, and information (up from 60 percent in 2016). The popular applications for video conversations include WhatsApp (62 percent), Skype (20 percent), and others (17 percent).

Generation Z: 28 percent of parents allowed screen time for their children under the age of one, 27 percent for children under the age of two, and 45 percent for children two to six years old. Average screen time for children six to nine years old was 2.7 hours a day.

97 percent of Israelis search for information on products on the internet before making purchases.

Social media networks – 45 percent of Israelis are active on online networks and communities. Of teenagers—93 percent use WhatsApp, 72 percent use Instagram, 63 percent use Facebook; 47 percent experienced shaming in 2017. Of adults—87 percent use WhatsApp, 38 percent use Instagram, 80 percent use Facebook.

News sources – 62 percent of Israelis are consumers of news via the internet (up from 50 percent in 2015); 48 percent get their news from social media networks (47 percent in 2015); and 40 percent from television (down from 56 percent in 2015). When asked “What is the most reliable source of news?” 88 percent responded radio, 84 percent television, 75 percent internet news, 74 percent newspaper reports, 38 percent online posts, and 24 percent blogs. My colleague Dr. Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler, head of the Israel Democracy Institute’s Media Reform project, wrote that the latest data provides cause for “Cautious Optimism for the Established Media:”

The 2018 Israeli Democracy Index… reveals that since 2016, when public trust in the media fell to an all-time low of 24 percent, it hit rock bottom. The growth in public trust which we saw in 2017 signifies a trend evidenced in the fact that today 31 percent of the general population, and 33 percent of the Jewish population, report that they trust the media…

Data from other countries show that the drop in Israeli public trust in the media, followed by a rise over the last two years, mirrors similar trends in the United States, and the United Kingdom. It would seem … that social media … have begun to lose their sparkle. The last two years have increased public awareness of the biases built in to the social media platforms themselves; of “fake news” and how it is spread virally; of the involvement of foreign countries and political campaign managers in the cynical manipulation of public opinion via social media; and of the resulting social and political polarization. The public has come to realize that social media platforms are not the new foundations for an egalitarian public discourse, but rather—advertising brokers seeking to maximize their own profits.

And so, the public is yearning for a “responsible adult” who can provide the needed context and interpretation of the reality, and who is committed to pursuit of the truth.

It is possible that what we are witnessing is a reaction from groups in the Israeli public who oppose Netanyahu to claims that “the media are guilty,” leveled by the prime minister and his close supporters in recent years. Quite possibly, these groups believe that these all-out attacks on the media, while they may contain some kernel of truth, are also politically motivated. This realization has resulted in a significant boost in trust in the media among those on the left and in the center, who in any case are no fans of Netanyahu. Incidentally, the modest rise in trust among those on the right indicates that here too—some are also not easily buying into the prime minister’s claims.22

Here is a revealing anecdote: In late 2012, Nahum, an observant Jewish friend and former member of the Knesset representing the National Religious Party (religious Zionists), shared with me his wife’s story about a woman on the bus. Nehama, Nahum’s wife, takes a bus to work in Jerusalem that passes through Bnei Brak, an ultra-Orthodox town. At the bus stop, an ultra-Orthodox woman sat down next to her. Staring at Nehama texting on her iPhone, she asked if Nehama would be willing to teach her to text on her own iPhone and Nehama said yes. As the ultra-Orthodox woman was reaching for her iPhone, another cell phone rang. Quite surprised, Nehama asked about that phone and the response was: “This is my ‘kosher’ phone.” [‘Kosher’ phones are not connected to the internet.] At about that time, tens of thousands of ultra-Orthodox men, clad in black, filled Citi Field, home of the New York Mets, to rally against the “pollution” and “menace” of the internet—while, at the same venue, they learned at a “Kosher Tech Expo” about filtering technology that can enable web use.

A random woman on the bus, probably representing tens of thousands, symbolizes the deepening of the cracks in the walls of the ghettos surrounding ultra-Orthodox communities.

The digital revolution is one of the significant variables that could, potentially, affect integration in Israel’s divided society. In particular, it could affect the integration of the ultra-Orthodox minority (45 percent of men and 44 percent of women were internet users in 2017) and of the Arab minority (73 percent used online social media and 43 percent connected to Facebook several times a day). It is important to note: surfing the internet is expressly forbidden by rabbinical leaders of the ultra-Orthodox community. We can assume that the users access a variety of uncensored content that significantly influences their integration into the Israeli mainstream.

Such constraints do not exist in the Arab society. While exposure to the digital world is mainly spontaneous in the ultra-Orthodox sector, the picture is different in the Arab sector. Several studies have shown that investing in internet access and the functional use of the internet can provide a powerful and rapid socio-economic boost to both the Arab and ultra-Orthodox sectors in Israel and help narrow disparities in all fields. The Israeli Internet Association recommends combining three essential components:

A. Upgrading internet and cellular infrastructure in Arab communities, bringing them up to par with the infrastructure in Jewish communities.

B. Providing Arabic versions of public internet sites for the Arab society, especially the digital services and sites of government ministries and municipalities.

C. Enhancing digital education.

Summary

There is no doubt that the outstanding “hardware” achievements in the State of Israel are impressive. In addition to the achievements described above, we can also note Israel’s military excellence, health infrastructure, scientific breakthroughs, and more. All of these together built the material dimension, “the hardware,” which is one of the two clusters of variables that may guarantee the state’s stability and resilience over time. The other dimension is “the software.”

Software: Israeli Society—Diversity, Integration, and Divisiveness: An Analytical Perspective

At the end of the 20th Century, Israel celebrated the end of the first Jubilee to its existence; the first fifty years of Jewish statehood in Israel came to a close. The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995 marked an ominous start to the second half-century of Israel’s modern existence.

Today, more than 23 years after Rabin’s assassination, the precipitants of that traumatic event still exist and have become even more acute. Powerful forces are challenging the variables that promote integration in Israel’s diverse society; these forces are placing the kaleidoscopic character of Israeli society on the slippery slope of growing divisiveness.

Therefore, I wish to reiterate my main thesis: The State of Israel in the second decade of the 21st Century is still engaged in composing the first chapters of political sovereignty for the Jewish people after seventy generations without responsibility for political involvement. The discussion of Israel’s characteristics today is grounded in and drawn from this historical context. This part of the discussion examines governance over diversity in an age of transparency, in a reality of nascent infrastructure. The fact that Israel lacks a constitution is the substantial deficit intertwined in the two dimensions presented below: the structural and normative dimensions.

As noted, Israel has a set of “Basic Laws” designed to serve as a provisional constitutional framework. Nine of these laws define the formal procedures of Israel’s democracy, including Basic Law: The Government, Basic Law: The Military, and so on. Most of these laws do not have constitutional protections that would prevent them from being altered by a simple majority. The two latest additions to this set of laws—Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and Basic Law: Freedom of Employment—were supposed to mark the beginning of the formulation of a bill of rights, but since the two bills were passed in 1992 the constitutional process has been halted.

The lack of a constitution has existential and far-reaching repercussions. Unlike more substantive and developed democracies, Israel lacks the consensual underpinnings that stabilize governance and enable the inclusion of diverse views, outlooks, and beliefs. The members of civil society in Israel have never experienced the impact of a written constitution in democratic life; a written constitution has never guided their way of life as a sovereign-national collective.

The Structural Dimension of a Democracy Without a Constitution

Israel is a parliamentary democracy. Members of the parliament—the Knesset—are chosen in nationwide elections. There are no electoral districts like in the United States; the entire country is a single district. The only other democracies with one single nationwide electoral district are Fiji, The Netherlands, Moldova, Mozambique, Slovakia, South Africa, and Serbia. On Election Day, Israelis cast votes for a party list by placing a single slip of paper in an envelope in the ballot box. When the votes are tallied, the number of seats each party is awarded in the 120-seat legislature is determined based on each party’s percentage of the overall vote. Israel is one of the few democracies with a unicameral legislature. This parliament is among the smallest and youngest in the world, and the hectic, dynamic political agenda it is tasked with managing is unprecedented.

For over two decades, governance in Israel has been in a chronic crisis with clear and salient characteristics: ongoing political instability, uncertainty regarding government policy on critical-existential matters, signs of the possible collapse of parliamentarianism and, above all, a rise in anti-political sentiment. This sentiment is expressed in the public’s widespread revulsion from politics and a steady decline in public trust in the institutions of democracy. The fiasco of the “direct elections”23 that began in 1996 and culminated in the repeal of the law led to the collapse of the major parties, disrupted the workings of the three branches of government and muddied the discourse between them, and increased the personalization of politics.

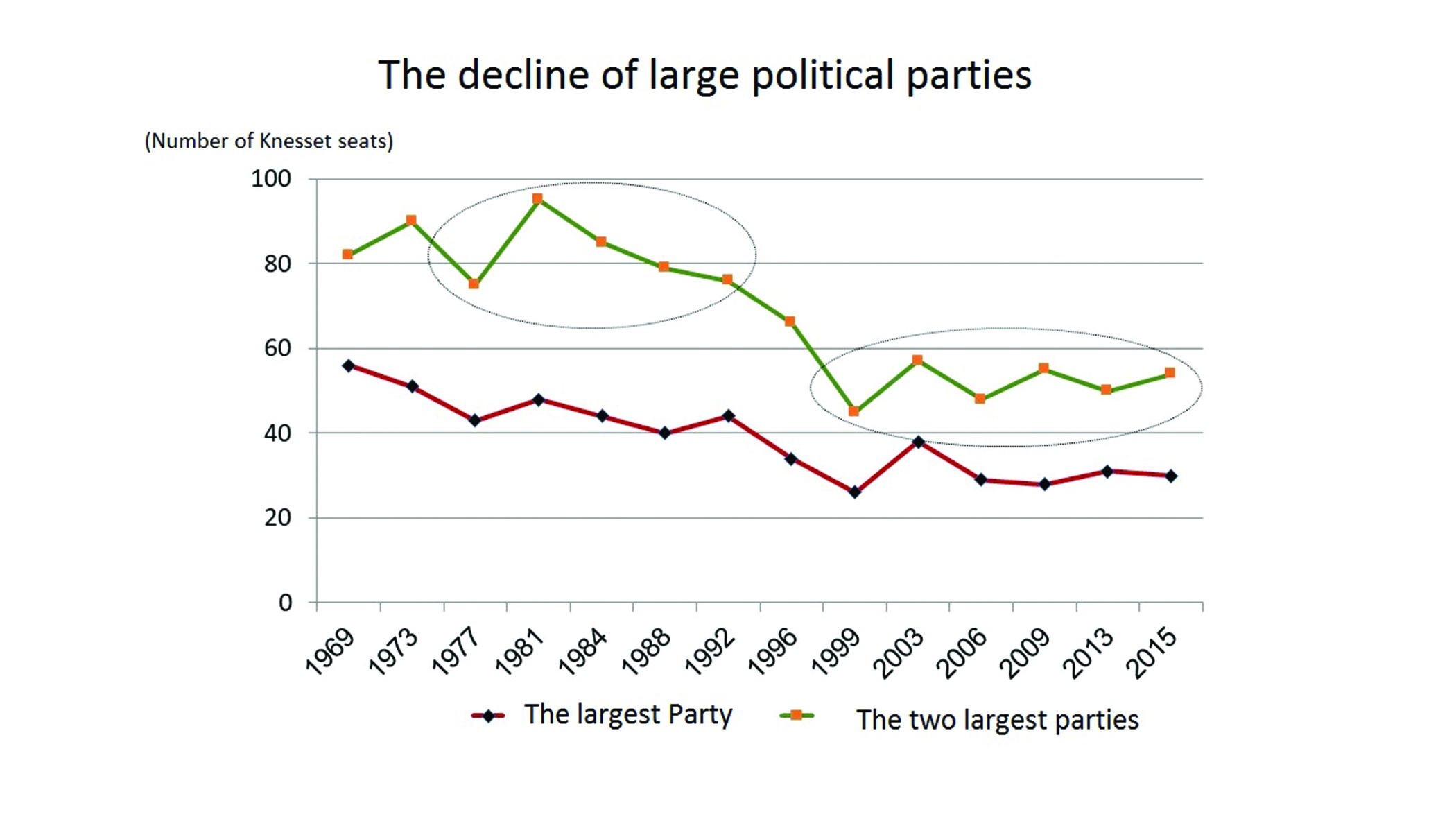

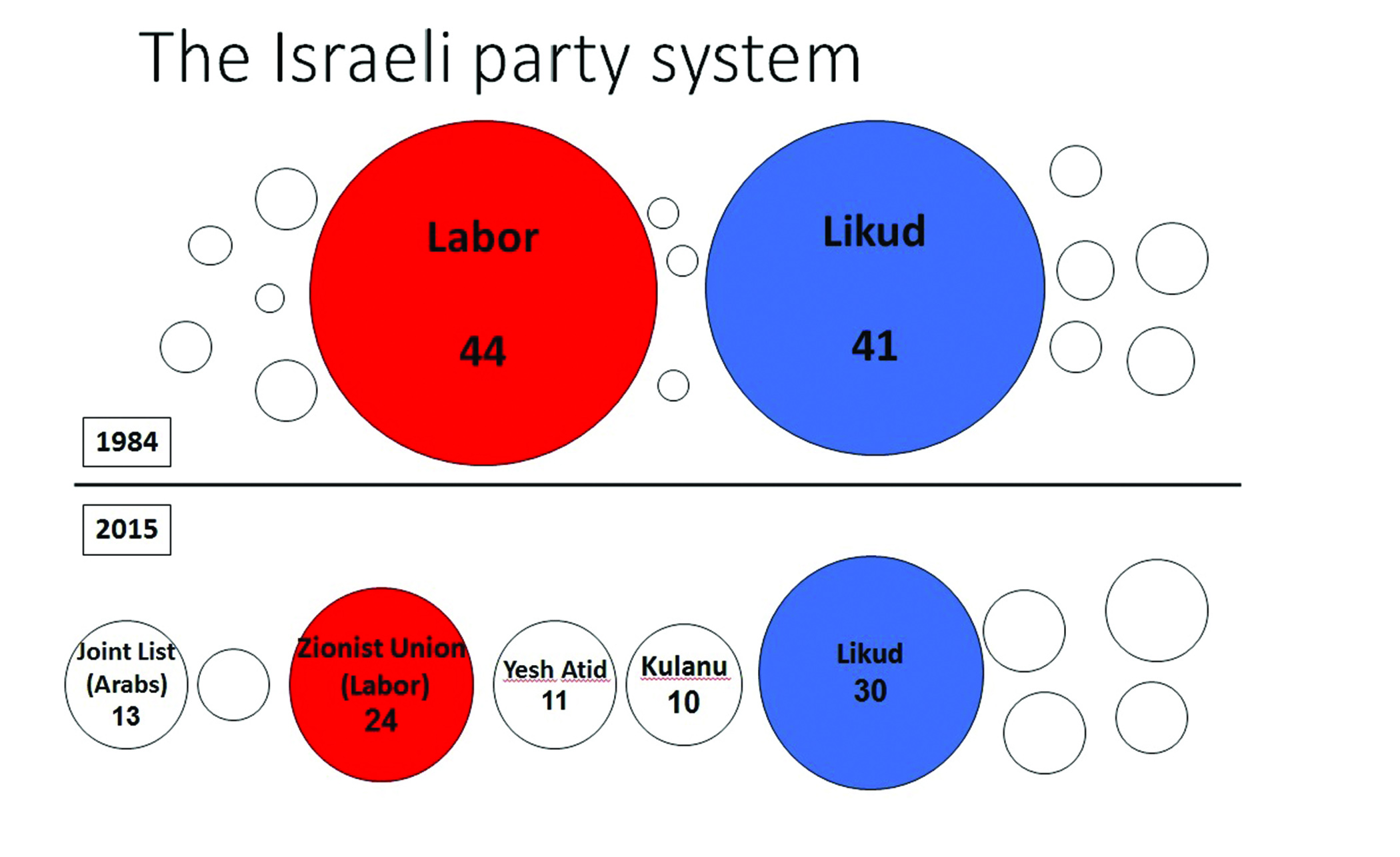

Figure 18 shows the sharp decline in the size of the major parties in the wake of the direct elections for prime minister in the 1990s. It should be noted that a single, hegemonic party ruled in Israel from 1949–1977 (the Labor Party in its various permutations). From 1977–1996, the two large parties (Labor and Likud) comprised over two thirds of the Knesset. The era of large parties in Israel effectively ended in 1996.

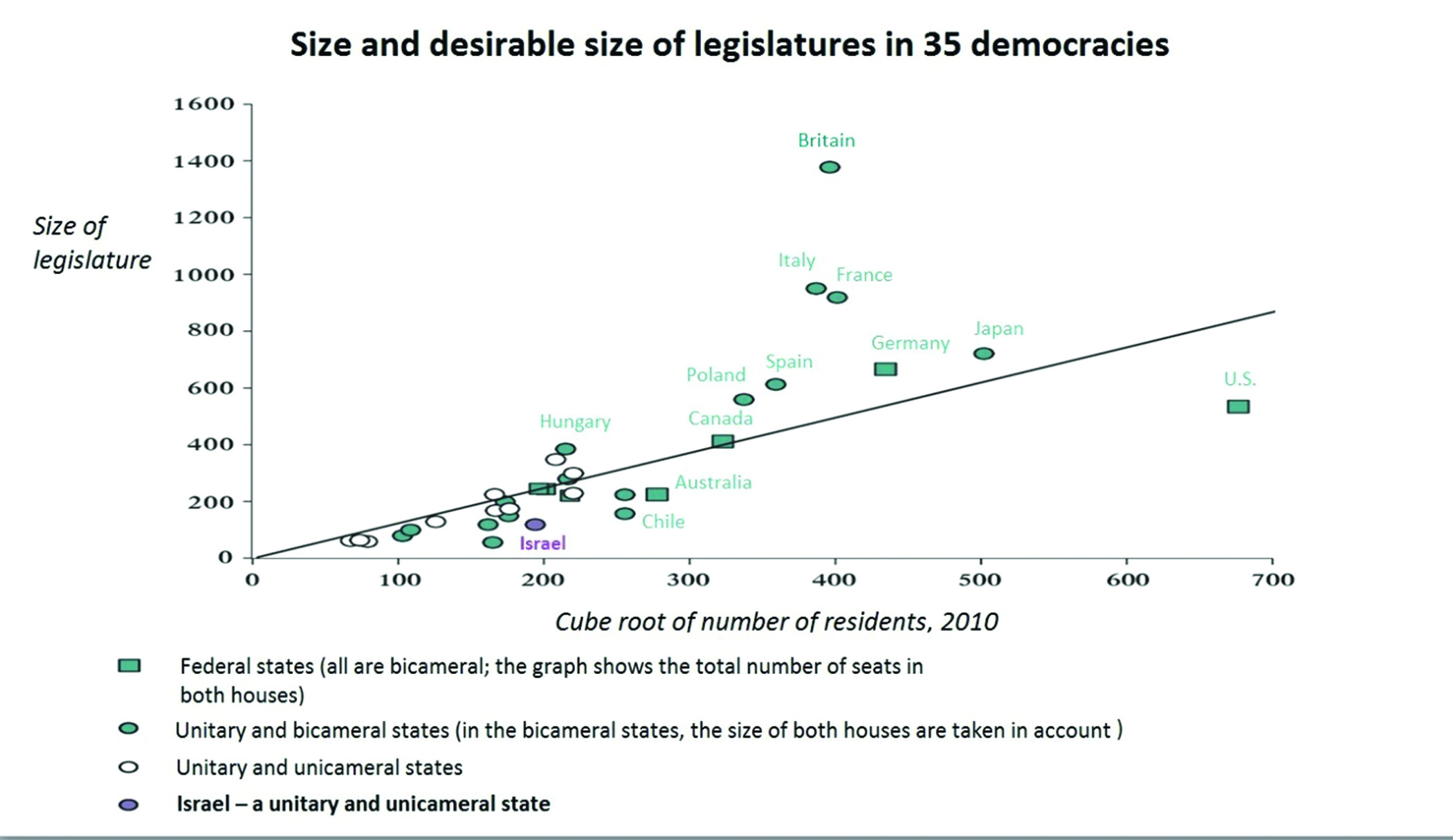

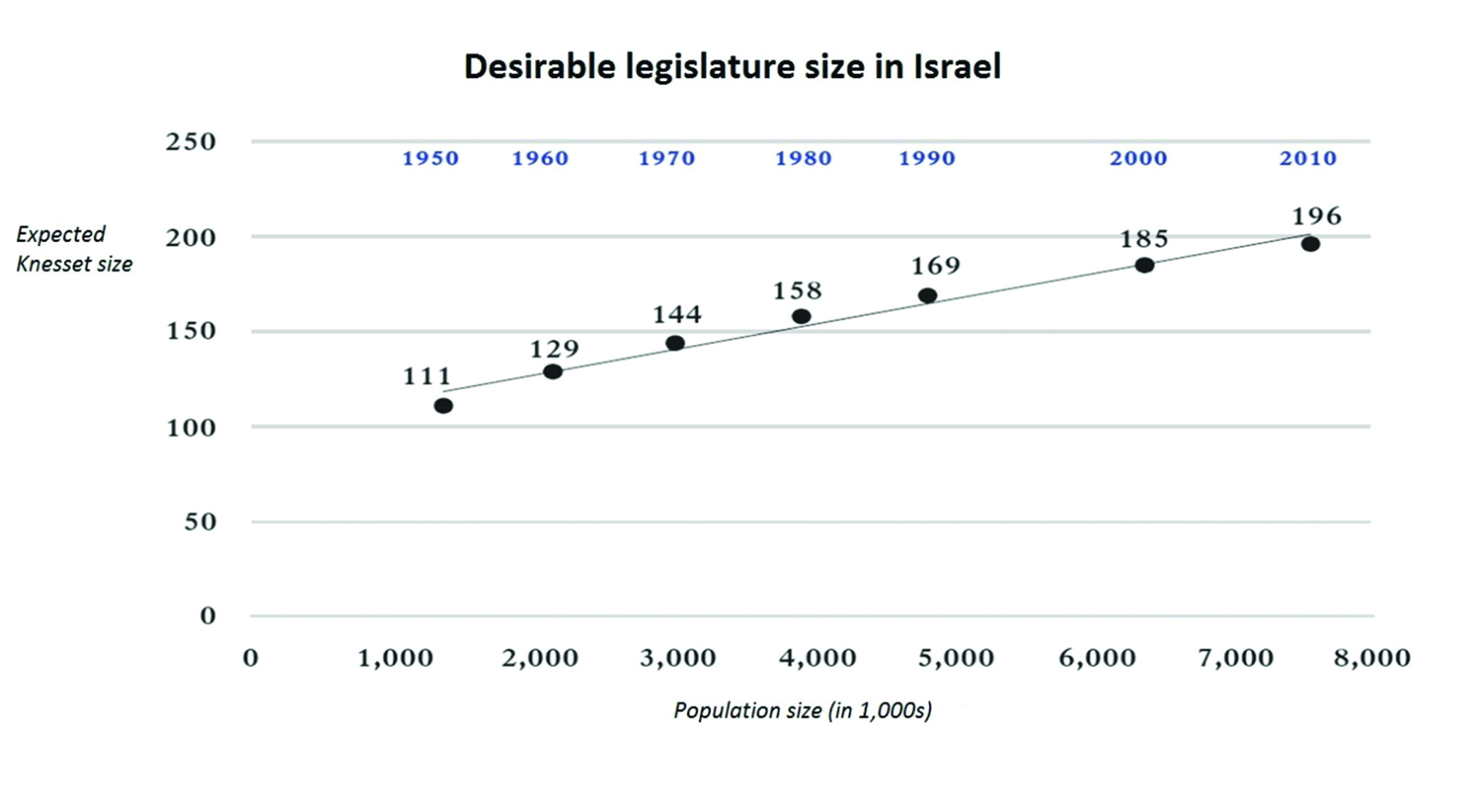

One of the sources of the weakness in governance is the size of the Israeli parliament. Figure 19 shows that Israel is both unitary (that is, has one unit of governance, as opposed to federal structures) and unicameral (a lower house only). Israel has one of the smallest legislatures in the democratic world. Figure 20 indicates the optimal size of the Knesset relative to the size of its population in different years.

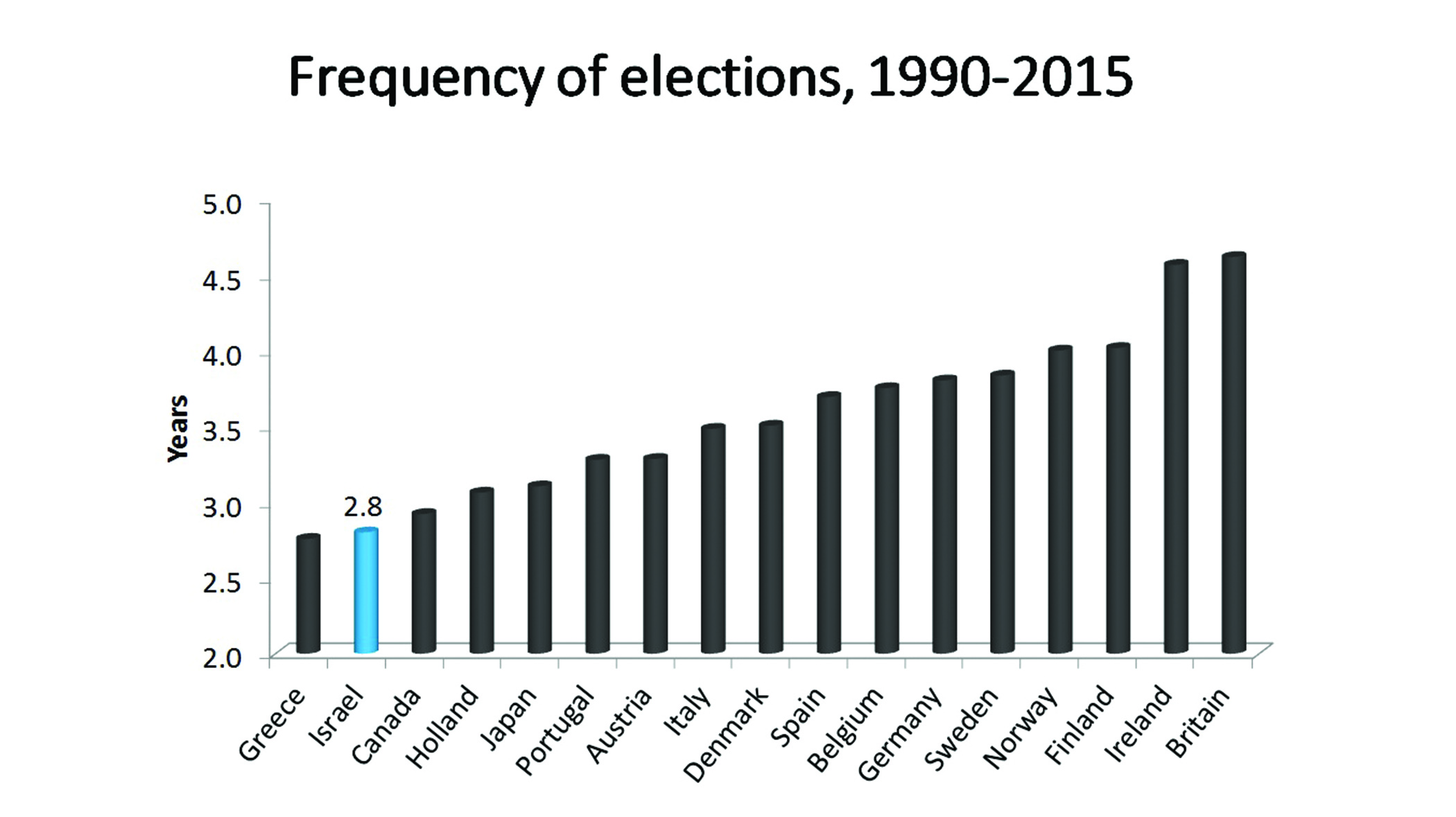

The emergence of a political map characterized by the collapse of the large parties posed a number of challenges for the Israeli democracy. The difficult situation in which the parliamentary democracy is immersed is partly attributable to the widening gap between the profile of an Israeli society whose size and needs are changing and the democratic institutions that are supposed to accommodate the changes and provide for the new needs—but remain immutable. Enlightened and developed democracies adapt their structure and functions to the changing needs of their societies. The Israeli democracy has failed to do this, as shown in Figure 20. Moreover, one of the signs of the chronic crisis is the frequency of elections, as illustrated in Figure 21.

The legislative branch has two primary responsibilities: to enact sound legislation and to conduct oversight of the executive branch. Figure 22 illustrates the substantial difference between the constellations of political parties in 1984 and 2015. Until 1996 (when the direct election system was implemented), the Knesset could handle both of its responsibilities despite its relatively small size. About 25 percent of the Knesset members from the ruling party (the prime minister’s party) served in the cabinet, leaving 75 percent available for parliamentary work in the Knesset committees.

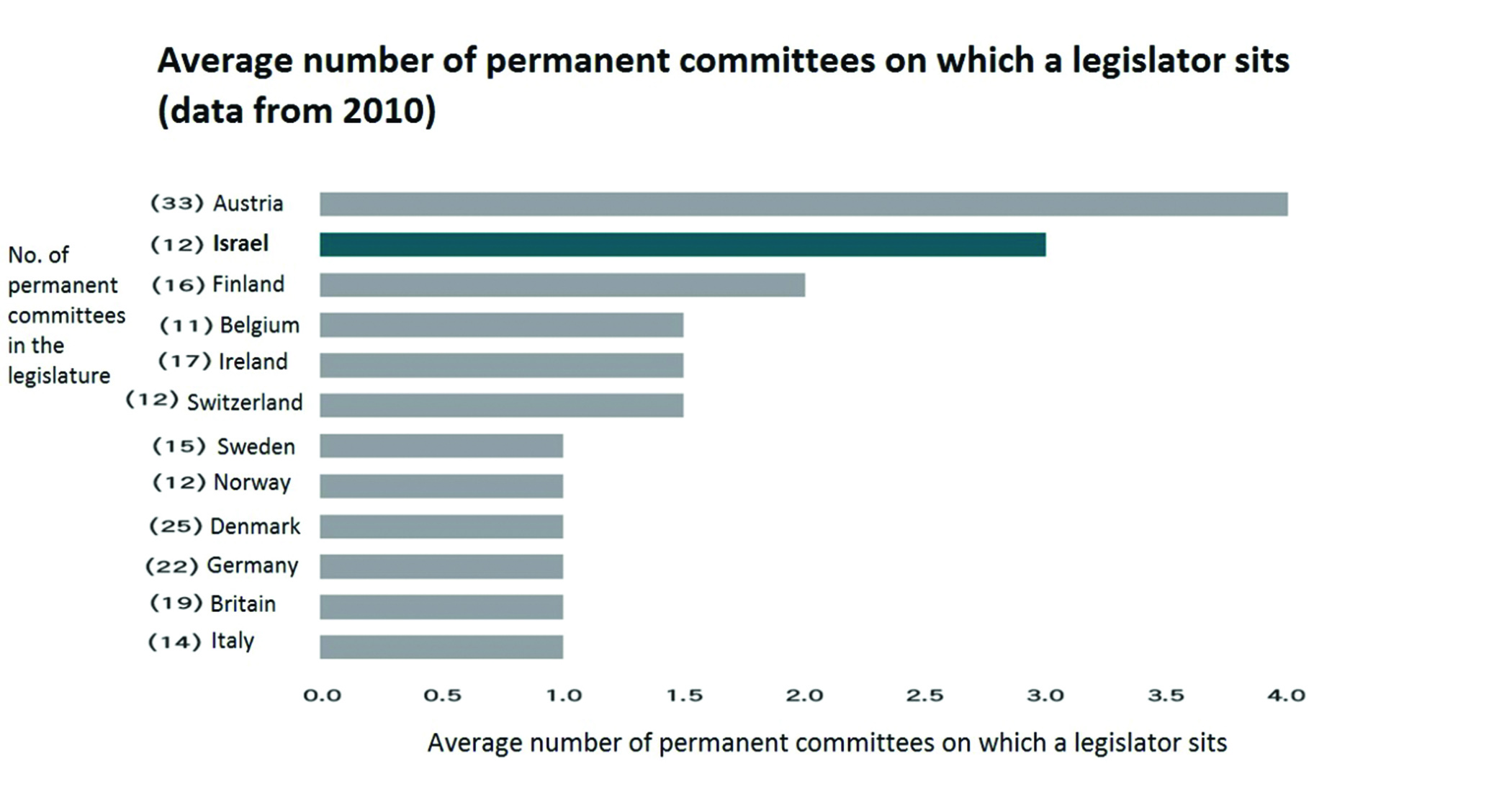

The reality changed. Figure 23 shows the comparatively high number of committees on which members of Knesset (MKs) serve: an average of 3.2 in Israel versus the OECD average of under 1.5 (according to data from 2010). It should be noted that the Israeli average includes opposition MKs, who are more available for committee work. In the outgoing Knesset, about 20 of the 30 MKs from the ruling party, the Likud, served as ministers or deputy ministers. Consequently, the burden of committee work fell upon the remaining Likud MKs, who served on an average of over four Knesset committees.

The chronic crisis described above has repercussions on the capacity to govern. The heart of the political system is mired in an amazing paradox: On the one hand, the political agenda in Israel is more jam-packed than that of any other democracy on earth. The national agenda includes matters that have fateful implications for the state’s character and future, such as contending with physical threats, managing diplomatic processes, and defining the state’s borders. In addition, Israel is struggling with a crisis of identity stemming from disputes over the interpretation of a “Jewish and democratic” state.

Israel is still engaged in a fight for its physical survival in the face of external threats. Thus, the structural shoulders of Israeli democracy are fragile and vulnerable considering the heavy loads it must carry. In fact, there is arguably no other nation in the world with such a complex load of issues on its public agenda. Each of these issues cries out for a stable and solid foundation.

On the other hand, for a quarter of a century, Israeli prime ministers have been held hostage to the demands of small parties they need to preserve their coalition. This situation hampers governance and weakens the power of the prime minister.

The growing trend of personalization is another component of the chronic crisis of politics in Israel. The short episode of direct elections for prime minister undoubtedly contributed to this. However, the decline in the status of political parties was also, and perhaps primarily, driven by the surge of visual media. Indeed, this challenge was aptly expressed in the title of our series of roundtable discussions: “Governance over diversity in an age of transparency.”

In the competition for the citizens’ votes, the parties no longer present platforms and plans of action, but rather emphasize individual “brands.” These “brands” are presented and thus perceived as exclusively fit to govern. This development, which has become almost universal, poses a threat to the essence of a democracy based on the rule of law and institutions.

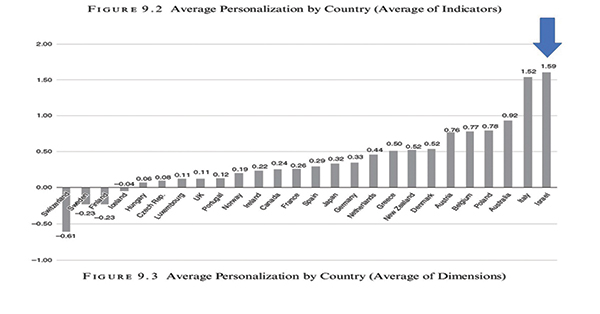

Figure 24 illustrates the extreme extent of personalization in Israel relative to other democracies. The data is from a comprehensive IDI study led by Prof. Gideon Rahat.

These rankings of personalization represent an average of eleven indicators; the value of each indicator ranges from two (2) to minus two (-2):

2 = a high level of personalization

1 = moderate personalization

0 = no clear trend of personalization

-1 = moderate depersonalization

-2 = a high level of depersonalization

The authors note that this is a rough scale in light of the nature and quality of the data. The eleven indicators, grouped in three categories, include:

Institutional personalization:

1. Changes in the elections system toward a more personal system (for example, from a closed list to an open list).

2. Changes in the election of the leaders of the executive branch at all levels (national, regional, local) to a direct election system.

3. Changes in the powers of the prime minister and presidentialization.

4. Changes in the election of a party’s leader (from election by a party committee, for example, to a decision by a single leader or through primaries).

5. Changes in the election of a party’s list of candidates (from election by a party committee, for example, to a decision by a single leader or through primaries).

Media personalization:

6. Changes in media coverage—focusing more on politicians and less on parties.

7. Changes in inclusion (or exclusion) of the names of leaders in the names of their election lists.

8. The number of Facebook posts (per month) by parties compared to the number of Facebook posts by politicians.

Behavioral personalization (politicians and voters):

9. Changes in party voting versus personal voting (for a party or a leader, and/or a change in the use of personal motifs).

10. Changes in the ratio of governmental bills to private member bills.

11. Ratio of “Likes” on Facebook—politicians versus parties.

The Normative Dimension of a Democracy Without a Constitution

The lack of a constitution leaves Israel without the “operating software” for its democracy. This is particularly salient in the various dimensions that form the normative foundation of Israeli democracy—that is, the consensual underpinnings that stabilize governance and enable the inclusion of diverse views, outlooks, and beliefs. Furthermore, the primary impact of this shortcoming is that it hampers and undermines the final stages of formulating a national identity and a coherent national consciousness.

National Identity

The two fundamental clusters of factors that are supposed to define the identity of Israel as a single collective are the particular and the universal, the Jewish and the democratic. Israel formally declares its identity as “Jewish and democratic,” based on its Declaration of Independence (May 15, 1948) and the preamble to the two basic laws enacted in 1992: The Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty and The Basic Law: Freedom of Occupation. However, substantively, the two components of this declaration are in deep dispute.

The particularistic characteristics of a nation are defined by the collective identity of the individuals and groups that comprise it. As Samuel Huntington notes, a nation is “a remembered community, a community with an imagined history, and it is defined by its historical memory of itself.”31 A nation cannot exist without a common national identity ingrained in the minds of its members as a shared memory of struggles and victories and defeats, heroes and villains, enemies and wars. According to these criteria, Huntington continues, the United States at the beginning of the 19th Century cannot be defined as a nation because it lacked a national history and had no national consciousness. The Civil War was the high price the United States paid to become a nation. The war gave birth to the American nation, whose characteristics were shaped in its wake. In the post-war years, American nationalism and patriotism were forged, as Americans came to identify unconditionally with their country. Prior to the Civil War, Americans spoke of their country in the plural, as “these United States.” After the war, they used the singular: “the United States.” As President Woodrow Wilson noted in his Memorial Day address in 1915, the Civil War engendered something new: “a national consciousness.”32

The Jewish people simply lack the natural propensity for political sovereignty, being that they spent 2,000 years as a stateless, wandering people adrift in exile. This has repercussions on how Jews experience their newfound political sovereignty. Israeli democracy is still under construction, with a national identity crisis supplying constant friction.

The Hebrew language is a noteworthy exception. The Hebrew language, spoken today by all Israelis, serves as a firm basis for establishing the required characteristics of a shared national identity. The revival of Hebrew was one of the first achievements of the Zionist movement. Zionism inherited an abundance of Hebrew prose and poetry, Hebrew translations of world classics, and, of course, Hebrew magazines and newspapers. This remarkable success notwithstanding, it never created a strong enough foundation for a new and autonomous Jewish identity that could provide the secular basis for democratic life in Israel. To be sure, the renewal of the Hebrew language was a seminal achievement. It contributed to establishing the cornerstone for a shared national consciousness, and, as such, it provided the foundation of solidarity in the early days of political nationhood, an anchor for contending with the challenges of the particularistic elements in the collective identity. Still, it is not clear to what extent national consciousness has developed in Israel or whether it can be said that Israelis share a common historical memory. The stumbling block is the lack of consensus, in fact the deep dispute, regarding the particularistic (“Jewish”) and universal (“democratic”) components of Israeli identity.

The Gordian Knot: Nationhood and Religion

From a historical perspective, religion is what defined the Jewish nation. In fact, the Jewish nation is the only one defined by religion. On the other hand, the liberation movement of the Jewish people, Zionism, which rebelled against the centrality of religion and against the political passivity that characterized Jewish life for seventy generations, was a secular movement in all respects. Thus, today there is no consensus on the characteristics that define Israel’s identity as “Jewish and democratic.” On the contrary, these characteristics are the source of deep discord within the very binds that are supposed to help unify the fractured country and facilitate co-existence. The definition of the “Jewish” characteristics has been under the control of an Orthodox Jewish monopoly, and the “democratic” values of this Jewish country are threatened by the ever-growing voices of ethnocentric nationalism. The principal challenge in the particularistic dimension of Israeli identity is to define the role of religion in the national consciousness of Israelis. The institutionalized Orthodox monopoly over the traits of the Jewish collective identity and certainly over religious matters in Israel leaves little space for other religious definitions, including Conservative and Reform Judaism. This disagreement lies at the heart of the crisis of identities in Israel.

In recent years, the IDI’s Democracy Index has addressed the question of the balance between “Jewish” and “democratic,” and how Israelis view this question. The answers reflect the weight of particularistic values versus universal values in the identity of Israelis. In addition, in light of the Orthodox monopoly over the Jewish particularistic dimension, these answers provide an indication of how Israelis will act when religious values clash with democratic values. In 2017, only 12 percent of religious respondents, compared to 61 percent of secular respondents, said that the Jewish dimension is too strong. The data was similar in 2018: 8 percent of religious respondents, compared to 61 percent of secular respondents. On the other hand, in 2017, only 8 percent of secular respondents said that the democratic dimension is too strong, and 9 percent answered similarly in 2018, compared to 44 percent of religious respondents in 2017 and 46 percent in 2018. (Among Arab citizens of the State of Israel, in 2018, only 8 percent of the respondents said that the democratic dimension is too strong, compared to 80 percent who contended that the Jewish dimension is too strong.)

Disharmonious Cultural Differences

Francis Fukuyama: “If we do not agree on a minimal common culture, we cannot cooperate on shared tasks and will not regard the same institutions as legitimate…when a stable, shared moral horizon disappears and is replaced by a cacophony of competing value systems, the vast majority of people do not rejoice at their newfound freedom of choice. Rather they feel an intense insecurity and alienation because they do not know who their true self is.”33 In Israel today, there is a wide range of disharmonious cultural differences that exacerbate an identity conflict.

The roots of this disharmonious cultural differences go back to the founding days of Israel. In the Land of Israel, the Zionist founders sought to forge a new society and a “new Jew,” who was defined by secularism. Thus, cut off from their shared cultural past, the Jews of Israel had no foundation of cultural continuity on which to build their new state. Other than the establishment of Jewish self-determination, the way of life and fundamental values of today’s Israel have not been consistent with the vision and worldview charted by the country’s founders. The secular revolution of the Jews did not last long enough to build a secular foundation that could offer alternative sources of interpretation and meaning for Judaism. No cultural transformation took place and the “new Jew” sketched out by the secular Zionist founders was short-lived.

To be sure, the Zionist horizon of “a new Jewish society” and “a new Jew” was too narrow. It was based on the worldview of pioneers from Eastern Europe and on breaking away from the cultural heritage of two millennia. This made it more difficult to lay the foundations for a shared culture. This is the source of the contemporary reality, of the disagreement and divisiveness, and the ascendance of the element of “otherness” rather than diversity. In retrospect, the ethos of manifest destiny among the Zionist pioneers was a powerful engine that drove the miraculous revolution in Jewish life. This ethos catalyzed the development of the material infrastructure for establishing political sovereignty for the Jewish people in the Land of Israel. Certainly, the upside of the Zionist revolution is very impressive. However, from the same retrospective view, we must also assess the downside and its implications. As noted, the prototype and focus of the pioneering ethos, the manifest destiny of Zionism, was “the new Jew,” whose personal traits were an antithesis to the exilic Jew. The identity components of “the new” were compressed into “Hebrewism,” which became the salient cultural symbol and watchword of the rebellion against the religiousness of “the old” exilic world. The pioneering ethos and its identity components, however, were not sustainable over time. Within a few decades of the state’s birth, the pioneering ethos eroded, along with the identity traits of Hebrewism. In practice, during Israel’s initial decades, the Orthodox religious monopoly over the definition of Jewish identity gradually took root, replacing Hebrewism.

This monopoly emerged in the context of a disharmonious mosaic, as Israeli society absorbed Jews of wide diversity from all corners of the world. The Zionist vision was challenged by different configurations of identity, including some whose components were based on religion, nationalism, and ethnicity, unlike the identity components of the Zionist “Mayflower” elites—the Ashkenazi pioneers from Eastern Europe, who regarded themselves as superior. Members of various groups that comprise the mosaic called “civil society”—ultra-Orthodox Jews, immigrants from the former Soviet Union, Arabs, national-religious Jews, Mizrahi Jews—feel that their identity is not accorded suitable respect by the outside world or by other members of the shared collective. As Fukuyama observes: “Identity grows, in the first place, out of a distinction between one’s true inner self and an outer world of social rules and norms that does not adequately recognize that inner self’s worth or dignity.”34

Melting Pot

The mass immigration of the 1950s tested the strength and sustainability of the concept of the “new Jew.” The leaders of the national liberation movement developed secular rituals, heroes, memorial ceremonies, poetry, literature, and the foundations of culture. For a certain period, there was indeed a sense of a new beginning. But the newness appeared artificial, not fully formed—and vulnerable.

The attempt to assimilate this wide range of cultures into the secular Zionist model failed. The country’s leaders sought to rapidly assimilate the immigrants within the existing culture in Israel and treated their unique cultural traditions as secondary and even irrelevant. As noted, the vision of the ingathering of the exiles and its central ethos—the “melting pot”—were the focus of Zionist activity in the State of Israel’s early decades. This ethos aimed to mold the ingathered exiles in the image of the state’s founding fathers. But the elites that headed the nascent state were ill-equipped to shape the identity of the new immigrants. Most of the immigrants from Islamic countries and some of those from Europe (primarily Holocaust survivors) were religious. The new immigrants were not driven by Zionist ideology. About half of them arrived in rescue operations from Islamic countries that were at war with Israel; the other half were Holocaust survivors who had already begun arriving on Israel’s shores in clandestine immigration missions prior to the establishment of the state.

Against this background, two elements should be emphasized: First, the principle of “negation of the exile” had no chance of striking roots in the consciousness of those whose identity was steeped in the Jewish tradition. In fact, the most dramatic effect of this immigration was that it brought “home” the tradition, despite the effort to negate the exile. Secondly, in the process of absorbing the mass immigration—fulfilling the vision of the ingathering of the exiles—a geographic periphery was created that became, almost from the first day, a cultural periphery. The geographic-cultural periphery was perceived in the collective consciousness and in its own consciousness as secondary, if not to say inferior.

Without a constitution and bill of rights, the Israeli democracy—certainly in its early days, but later too—did not guarantee a minimal degree of equal respect as part of individual rights and the rule of law. Furthermore, the reality of a territorial-cultural center trying to impose its values on the periphery via the “melting pot” made it impossible to accord an equal degree of respect. The deficit of respect developed in the geographic and cultural periphery and created feelings of exclusion and discrimination that persist today in various levels of intensity. The unanswered demand for recognition of ethnic identity in the periphery led the immigrants to enlist in the religious counter-revolution. Today, decades later, the “politics of identity” is strengthening, reinforced by the deficit of respect, and looms as a persistent conflict. To quote Fukuyama again: “Current understandings of identity…threaten free speech, and more broadly, the kind of rational discourse needed to sustain a democracy. Liberal democracies are committed to protecting the right to say anything you want in the market place of ideas, particularly in the political sphere. But the preoccupation with identity has clashed with the need for deliberative discourse. The focus on lived experience by identity groups valorizes inner selves experienced emotionally rather than examined rationally.”35

In the Israeli context, I believe that the basis of agreement—the condition for achieving harmony—must come from a deeper clarification of the meaning of the words “Jewish” and “democratic,” and especially a clarification of the balance between them. It is a challenge to construct a language that can bridge different cultures and identities and allow for co-existence.

In this reality, what type of potential is there for tolerance, when there are so many conflicting identities? The Israeli cultural mosaic is made up of such a vast array of tiles that are foreign to one another that societal discord is inevitable. This reality poses a challenge for those who seek to foster harmony through dialogue and some sort of broad social consensus.

The Territorialization of Identity

Another key factor fueling the divisiveness in Israeli society and significantly hindering the crystallization of a collective identity is the dispute over the territories Israel captured in 1967. Indeed, Israel’s territorial identity is a subject of fierce disagreement between those who seek to resolve the conflict with the Palestinian neighbors predicated on a return to the 1967 borders and those who stake a claim to all of the territory between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

For over fifty years, the democratic State of Israel has maintained a military regime to occupy and control the territories it captured in war and the lives of its non-Israeli residents. Israel has not annexed these territories; their residents are not citizens and lack political rights, and there is an alternate set of Israeli laws applied in the occupied territories. Thus, these territories, which are not part of sovereign Israel, have led to what I call an artificial and anomalous “territorialization,” which is the opposite of an organic territorialization. The latter defines the political borders of the collective that lives in the territory and establishes the various features of the collective’s political sovereignty within these defined borders, unlike the Israeli system, where the eastern border remains undefined.

The focus on the question of borders has strengthened the territorialization of national-cultural values. It has become a dominant factor in the forging of political-economic-social policy in Israel, largely through the diversion of resources to the territories. The state has invested enormous resources to pave roads, develop infrastructure, and wage legal battles with the Arab residents of the territories, all while deploying soldiers and police within an occupied territory that lies outside the state’s recognized borders. These policies have created an artificial physical separation between Jews and non-Jews. It is the height of irony that this territorialization is taking place in a diasporic nation that has no history as a territorial nation and has yet to achieve full sovereignty. Territorialization has brought a return to the ghetto ways that Zionism rebelled against. However, unlike the ghetto in the Diaspora, the ghetto in the occupied/liberated territory enjoys the physical protection of the state. This artificial territorialization has strengthened the feeling of transience and the lack of a complete sense of “being at home” for at least half of the Jewish population in Israel.

Conclusion

The creation of a constitution when a nation is born is analogous to the ceremonial circumcision of a newborn Jewish male: it is a cornerstone in establishing national identity. This is what happened in the United States. Israeli democracy, however, is a ship of state that left the shipyard prematurely: not all the bolts are fastened, not all the seals are tight. The psychological gulf between the two democracies is as wide as the distance from 18th-century Philadelphia to 21st-century Jerusalem. The intellectual genius and political will of the founding revolutionaries, Anglo-Saxon gentlemen, educated humanists of the upper social classes, gave rise to a constitution that, with periodic amendments, has determined America’s democratic character. This did not happen in Israel and perhaps could not have happened.

The goal of creating a normal reality in Israel was of paramount importance to the founders of the state. At the helm of Jewish nationalism was a pragmatic leader who faced a nearly impossible reality and lacked the ability to educate the people of his nascent state about the principles they would need to adopt. He was an illustrious statesman but not an educator, and there was no political ally at his side to take this role. A contrast with the three founding fathers of the United States immediately comes to mind: In Israel there was no equivalent to James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay. These three men authored The Federalist Papers—an in-depth guide for the American democracy, a sort of “pedagogical” manifesto that took a long-term view of the matters at hand. It is self-evident that this collection of 85 articles provided a blueprint for the normative foundation of the U.S. democracy. Ben-Gurion, however, was a priest without a prophet. He envisioned the creation of the state but had no long-term plan for its political content and no Federalist Papers. No equivalent document was written in Israel because the founders of the state lacked a sound foundation of political-state theory and views. This is in marked contrast to the founding fathers of American democracy, whose political beliefs were grounded in the implications and conclusions of such theories and views. There was no Alexis de Tocqueville to guide the actions of Israel’s founding fathers. This absence is not only an attribute of the Zionist deficit but also reflects the fact that the Jewish people had no tradition of political sovereignty.

A Personal Note

Throughout my entire adult life, I have been driven by a feeling of partnership in a historic “Genesis”—in the creation phase of Jewish political sovereignty. Recently, I’ve asked myself whether second- and third-generation Israelis share this sense of Genesis. The Zionist revolution created a watershed (or fault line, depending on who you ask) event on May 15, 1948: on one side is two thousand years of Jewish history, and on the other side is the existence created by Jewish political sovereignty. On one side is a multi-faceted cultural kaleidoscope of languages and identities and traditions that were formed across the world over dozens of generations. On the other side is the sputtering national effort to build a single, unified people.

This fault line between the Jewish past and the Zionist present is part of the personal biography of every member of my generation born in Israel around the time of the founding of the state. It is part of our memories and our way of life. The fault line reminds us of the historical primacy—an era of Genesis—that is part of our biographies. This feeling has faded, and I don’t believe my children or my grandchildren can relate to it. The existential distance that separates my children and grandchildren from this watershed fault line is not far. They and members of their generations are still children of the rebirth of Israel. This is a historical fact, and it is part of their responsibility for the future of the state. It is a responsibility that their contemporaries in territorial countries do not share. The distance in consciousness from the same line, however, has grown quite significantly. This raises the question of how we can internalize the conception of Genesis in the minds of these generations and instill the sense of historical primacy of their Jewish heritage. Also, how can we foster this connection in Diaspora Jews? I don’t have an answer, but of one thing I am convinced: A brave embracement of this connection may be a source for hope.

Author’s Note

Parts of this paper, as well as its title, were taken from the author’s book, slated to be published in the Fall of 2019 by the Hoover Press.

Arye Carmon is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution. He is the founding president the Israel Democracy Institute, which he helped form in 1991 to strengthen the structural and normative foundations of Israeli democracy.

Supporting Data

Figure 1. Trends in fertility rates among Jewish and Muslim women in Israel2

Figure 2. Fertility rates for 20143

Table 1. Fertility rates in Israel by population groups4

Table 1. Comparative perspective of fertility rate5

Figure 3. Israel—Employment rate up 10 percent from 2002 to 20166

Figure 4. Comparative perspective on employment increase, men vs. women, ages 25-647

Figure 5. Employment and ethnicity in Israel, men and women, 25-648

Figure 6. The ratio between GDP per capita in Israel and OECD benchmark countries9

Figure 7.Debtratio in Israel10

Figure 8. “Israel’s Culture of Exits”—10-year trends, total number of exits by Israeli high-tech companies11

Figure 9. Foreign R&D centers in Israel12

Figure 10. Israeli scientific prowess in global comparison13

Figure 11. Israeli R&D expenditures14

Figure 12. Global innovation index15

Figure 13. Innovation at Israeli universities16

Figure 14. The water challenge17

Figure 15. Comparison of wastewater recycling18

Figure 16. Israeli wastewater innovation19

Figure 17. Changes in Israel’s water sources20

Figure 18. The decline of large political parties in Israel24

Figure 19. Size of legislatures around the world25

Figure 20. Israel’s desirable legislature size26

Figure 21. Frequency of elections in comparative perspective27

Figure 22. Israel’s political parties28

Figure 23. Average number of permanent committees on which a legislator sits (2010)29

Figure 24. Average personalization by country30