- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- US

- World

- Economic

- Contemporary

- Campaigns & Elections

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- The Presidency

- History

Electoral analysts are rolling out their models of voter behavior to predict the outcome of the imminent general election. These “scientific” efforts at prophecy, increasingly elaborate and arcane, boil down in the end to gauging voters’ evaluations of three simple questions for each candidate: What have you done? What will you do? and Who are you?

The first question—famously posed to voters by Ronald Reagan in 1980 as “are you better off than you were four years ago?”—is the main question applied to the candidate of the incumbent party, and especially, as in this presidential contest, to an incumbent himself. Academic modelers refer to this dimension as retrospective voting, or a referendum on the past.

What will you do? is the question asked first of the challenger. A challenger’s record—say, as governor—may be informative, but the challenger, unlike the president, has not directly affected the lives of most people. Voters therefore want to know what the challenger would do, so that they may compare him with the incumbent and judge whether the challenger’s intended course of action warrants, in Alexander Hamilton’s felicitous term, the incumbent’s “dismission.” Voters for the most part are future-oriented creatures. A challenger who runs as a potted plant, counting on people voting solely to reject the incumbent, had better pray for something as awful as a depression. Otherwise he will stand little chance. In truth there is very little pure retrospective voting. The incumbent’s record serves mostly as an indicator—an experimental estimate—of his future course and of whether “to continue him in the station, in order to prolong the utility of his talents and virtues,” as Hamilton wrote.

Finally, the question Who are you? reminds us that people vote not just on the basis of a record or a future program, but, given the peculiar challenges of the presidency, for a person with certain qualities. Voters wonder about a candidate’s readiness to handle those unforeseeable crises that inevitably emerge (what Hillary Clinton unforgettably referred to as the three a.m. phone call). They think about a candidate’s qualities or virtues and how these correlate with good performance in office. They consider what values a candidate symbolizes or embodies, such as being “a man of the people.”

The complex judgments relating to this personal dimension may weigh less heavily in the voters’ decision than their evaluation of the first two factors. But what takes place during presidential campaigns—the occasional revelation of new information about the candidates’ past and the scrutiny given to how candidates hold up under pressure—testifies to the importance of the judgments of character and virtue. A notable attribute or a marked deficiency can determine the outcome.

HOW TO HANDLE A CRISIS—OR CONGRESS

This year, many aspects of personal qualities seem to be off the table. One is consideration of the candidates’ military records, which has been an issue in every contest dating back to at least 1988, whether it was a matter of the candidates’ heroism or valor (George H. W. Bush, Bob Dole, John Kerry, and John McCain) or whether questions were raised about service itself or special treatment (Bill Clinton, George W. Bush). Neither Mitt Romney nor President Obama served in the military. Also off the table are matters relating to the candidates’ personal turmoil, substance abuse, or infidelity. Search the nation, nay the universe, and you will not find two more scrupulous and exemplary family men than Mitt Romney and Barack Obama. If there is any issue to be raised on this account, it will likely focus on their treatment of the family dog. As for substances—Obama’s youthful experimentation aside—Mitt Romney does not drink even beer, and President Obama during his famous beer summit looked as if he didn’t know how to.

Finally, there is very little chance that the issue of being able to handle an emergency, another matter that figured prominently in many recent campaigns, will be raised. We will hear criticisms, to be sure, of some of Obama’s foreign policy decisions, but that is not the same thing as doubt about the capacity and readiness to act. After all, Obama took the proverbial three a.m. phone call in authorizing the Osama bin Laden raid, and we have the official photos to prove it. On the other side, even though Mitt Romney has never directly had to handle a case of this kind, his evident maturity, steadiness, and long record of decision-making render it highly unlikely anyone would charge him with being unprepared.

In light of the absence of these matters, which made recent campaigns so bitter on a personal level—going right to questions of integrity and manliness—the 2012 race is likely to be remembered as much cleaner than usual. Which isn’t to say that other elements related to personal attributes will not call for voters’ attention.

It is difficult to identify the full list of special “talents and virtues” that have been proclaimed by, or on behalf of, candidates running for the presidency. One item that has certainly been important is military expertise and valor. Think of the number of candidates who have been lauded and promoted because of their military accomplishments (Washington, Jackson, William H. Harrison, Taylor, Grant, and Eisenhower, to name only some) and others who have been celebrated for their demonstrations of valor (including Teddy Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, George H. W. Bush, and John McCain). Another quality is that of being a statesman, a claim so elevated that it has been seriously made only on behalf of early presidents, such as Adams, Madison, and Monroe, who enjoyed the prestige of being Founding Fathers. Most candidates proclaiming mastery of the political art are compelled to offer themselves on the more modest ground of being commendable politicians. This ambivalent talent describes the bulk of candidates who have run for the office, from Martin Van Buren to Richard Nixon to Bill Clinton to George W. Bush. These men were said to have practiced a worthy, if not obviously noble, calling, and to have pursued it well.

Another talent or virtue is found in leaders of conviction, men admired for articulating a program or public philosophy. Included here are Abraham Lincoln (in 1860), William Jennings Bryan, George McGovern, Ronald Reagan (in 1980), and Barry Goldwater. Although the last three had extensive government service, their presidential campaigns made clear that being good politicians was not the primary talent touted on their behalf. These were men celebrated, at least by their partisans, for promoting a cause or set of ideas.

Two other qualities or virtues have been put forward, only much less frequently: the skill of the businessman and the virtue of the man of intellect. In the category of businessman might be placed Herbert Hoover and Wendell Willkie, both of whom were prominent in the world of commerce and had held no previous elective office. Yet neither made conducting business his premier talent in quite the way that Mitt Romney has. Yes, Romney admits having been governor of an important state, but in speech after speech, he emphasizes the skill set honed in running a business. In one typical formulation, Romney said, “I spent twenty-five years balancing budgets, eliminating waste, and keeping as far away from government as was humanly possible.” His proficiency as a businessman is much broader than making money. It represents a capacity to build and to fix things when trouble arises, like the failing project for the Winter Olympics. Knowledge of how the economy works, Romney insists, is all the more critical during an anemic recovery, and the challenge of reducing the federal budget will demand the skill of the most tested of managers.

Other presidential aspirants have put the competencies of the businessman at or near the top of their qualifications, including Mitt’s father, George Romney, Ross Perot, Donald Trump, and Herman Cain, but none became the nominee of a major party. We are about to find out if this quality can sell.

What of President Obama? The dimension of the candidate’s special talent or virtue, as an independent factor, is less important in a re-election campaign. What counts most, after all, are a president’s demonstrated skills in office. Even so, it is hard to think of any president who presents so different a defining virtue between his two races as Obama. In 2008, Obama was put forward as possessing a quality unique to him on the list of presidential candidates. He never cited his skill as a politician—he had only a scant record of service—and while he became known as a formidable orator, his rhetoric was not put primarily in the service of articulating a program or public philosophy. Barack Obama was celebrated as an inspirational leader, a charismatic in Max Weber’s sense of someone who gives birth to a politico-spiritual creed. Obama was a demigod, not only to many Americans but to millions across the world.

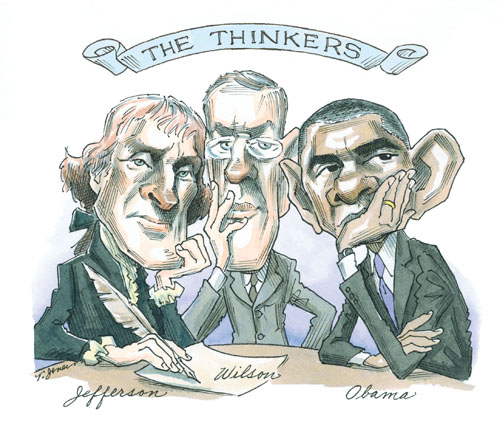

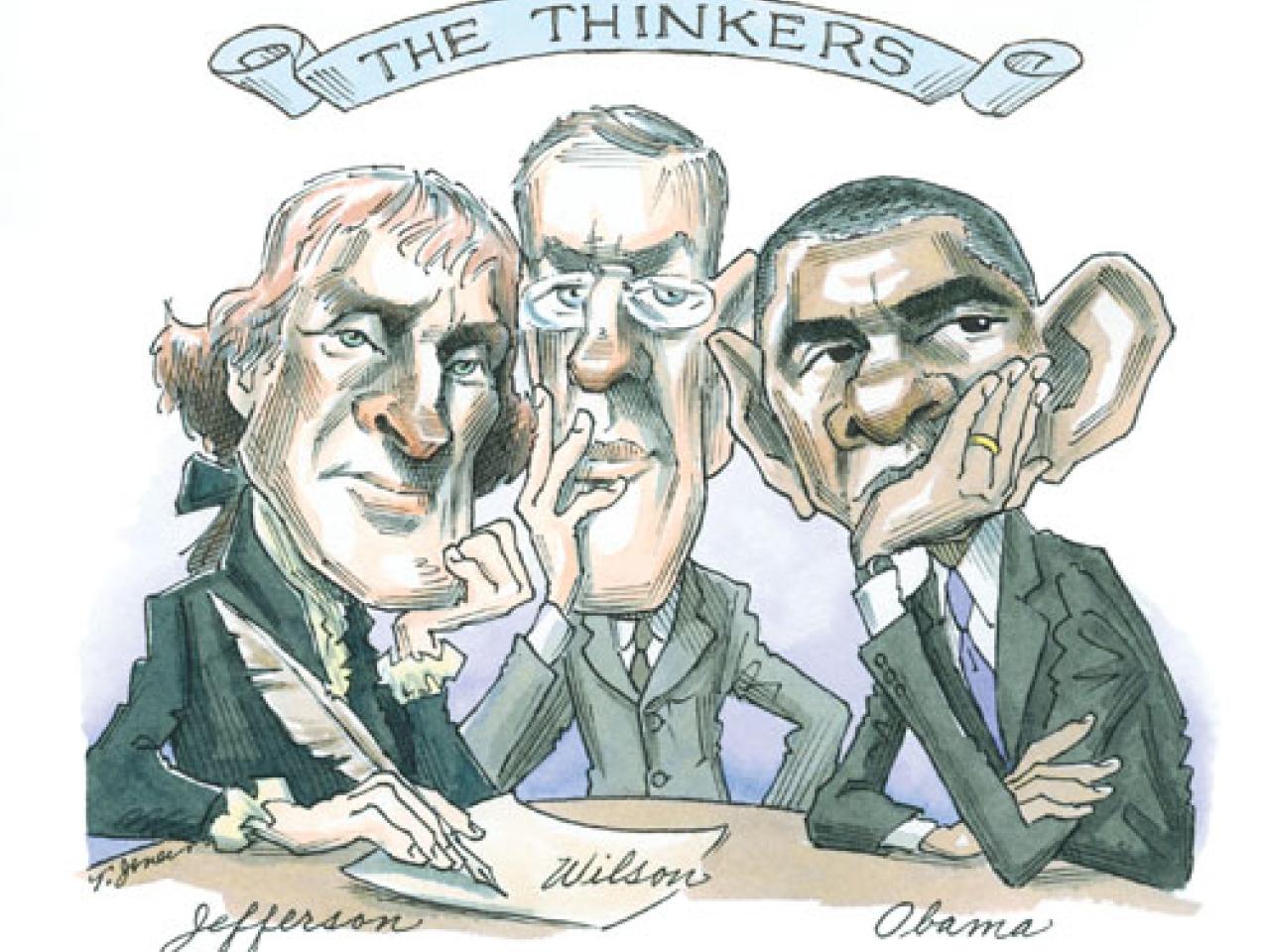

There is little chance of his offering this talent now. In a stunning metamorphosis, the president appears to have awoken one morning in November 2010 and looked down to discover that he had reverted fully to mortal form. And when he appeared in public, even in Europe, others could not fail to notice the very same transformation. The special virtue that his campaign will claim on his behalf this time is under intense debate. Some propose to cast him as an articulator of a public philosophy, though he has none that he wants to advance. Others prefer to cite his quality as an intellect or thinker, a talent that places him in a tiny group, composed of Thomas Jefferson and Woodrow Wilson, celebrated during their campaigns for their power of mind. After all, Barack Obama, like Woodrow Wilson, was a professor.

SOMETIMES SYMBOLISM IS OVERRATED

The 2012 campaign has shaped up as a contest between the businessman and the intellectual. Obama’s references to the “1 percent” and to Wall Street are targeted at Mitt Romney, and Romney has replied in kind, “We have a president who I think is a nice guy, but he spent too much time at Harvard.” Romney also went to Harvard, though he spent most of his time on what the intellectuals consider to be the wrong side of the Charles, where the business school is. Both men can claim an academic record of achievement, but where Romney immediately gravitated to the world of business, Obama spent much of his time in the academy, teaching law, and produced a literary memoir. There is no indication that Romney, who was deeply formed by his father, is either interested in or would be capable of such intense introspection, unless it would be to prepare a fifty-nine-point account of the development of his paternal and managerial skills. By the same token, it is difficult to imagine Barack Obama as the shareholders’ choice to run Bain Capital.

Beyond the special talents or virtues, voters look at candidates as symbols of the things they want to see validated and praised. In Obama’s case, many Americans were attracted to his candidacy for representing the idea of inclusion and justice and for providing a sign of the near, yet not complete, triumph over the national shame of slavery and discrimination. Obama’s nomination was counted a huge “first,” a breakthrough of far greater significance than the previous firsts of a female and a Jewish vice presidential candidate. And to Hillary Clinton’s dismay, her anticipated first as a female presidential nominee had to cede primacy to Obama’s stronger claim as an African-American. Obama was quick to acknowledge this achievement, joining with others in taking pride in the display of a more tolerant America.

And what of Romney? His nomination also marks an objective first, though Romney rarely calls attention to the fact that he is a Mormon. Besides revealing something of his personal style, this reticence reflects the recognition that this first is not being widely celebrated. Why? Most likely it has much to do with the disposition of those who distribute the awards for tolerance. These judges, deriving mostly from the intelligentsia, appear reluctant to celebrate Romney’s first for fear of diminishing the more prized achievement of Obama, as if the nation were incapable of celebrating more than one feat of tolerance at a time; or, seeing the success of so many Mormons, they may consider that this group does not suffer sufficiently from duress to warrant the acknowledgment of a first, although group success did not deter the widespread celebration of the vice presidential nomination of Joseph Lieberman, who is Jewish, in 2000. It might also be that many do not see Mormons as a genuine minority. Take away Mitt Romney’s religion and he looks, walks, and talks like the perfect WASP just as much as that other non-Protestant nominee, the Roman Catholic John Kerry.

The most likely explanation, however, is that the tolerance-anointers are not very excited about Mormons; they may even have friends who utter less-than-sensitive comments about them in private. This last possibility has been artfully deflected by the creation of the impression that only conservative evangelical Protestants oppose the election of a Mormon president. In fact, polls show that by far the greater opposition comes from Democrats.

IF I WERE A RICH MAN . . .

The symbolic dimension of the candidates also functions negatively, with many voting against the personal qualities they dislike or consider dishonorable. It has become commonplace to claim that many Americans despise the rich, especially when they think that their wealth comes from privilege rather than the striving of a self-made man. Romney is often portrayed in this light, though he fits the model imperfectly. He was born into affluence, but—unlike JFK or John Kerry—he acquired the greater part of his considerable fortune, thought to be in the neighborhood of $250 million, by his own efforts. This dislike of the rich, however, has been exaggerated; most Americans tolerate them reasonably well. Even on the left, and even in the case of persons born to privilege, like FDR or JFK, the rich can still easily pass if they make common cause with the party that professes suspicion of wealth. Their political stance is considered sufficient penance to absolve them of their crime, a tendency known in social science as Buffett’s rule.

The truly daunting challenge in America is for a rich person coming from affluence to make the case for wealth, which may be one reason why so few wealthy candidates for president have been willing to do so. Romney is facing a test that a Republican of much lesser means would not encounter. He has no choice but to double down, defending private property not only in the abstract but also in his own life. Obama faces a similar problem, though it is less acute. Like Romney, he would no doubt find it easier to defend intellect if he were not so conspicuously an intellectual himself.

These two abilities—making money and displaying intellect—ought to be qualities worthy of universal praise, as ways in which Americans distinguish themselves and show their excellence. Of course, both qualities can be pursued in an unjustifiable way, as in the case of the moneymaker who proceeds dishonestly or by destructive means (although economic advance frequently involves creative destruction), or the thinker who parrots trendy ideas and mocks orthodoxies (although good ideas often challenge traditional beliefs).

The regrettable fact today is that neither the intellectual nor the businessman much respects the other, and each seems to prefer discrediting his rival to joining in common recognition of the virtues of both. More important, there are votes to be had today in stirring up animosities. If it comes down to this, we can only hope the American people will have the good sense to be more repelled by the class-warfare rhetoric of the intellectuals than the enviable remuneration of the businessmen.