- California

A problem with anticipating American presidential elections: much like sports tournaments, they don’t always go according to plan; you don’t get the confrontation you desire.

It’s true in the case of men’s tennis—last weekend’s highly anticipated Wimbledon finals matchup between Rafael Nadal (22 Grand Slam singles titles) and Novak Djokovic (21 such titles) not panning out after Nadal withdrew from the tournament, prior to the semifinals, due to an injury.

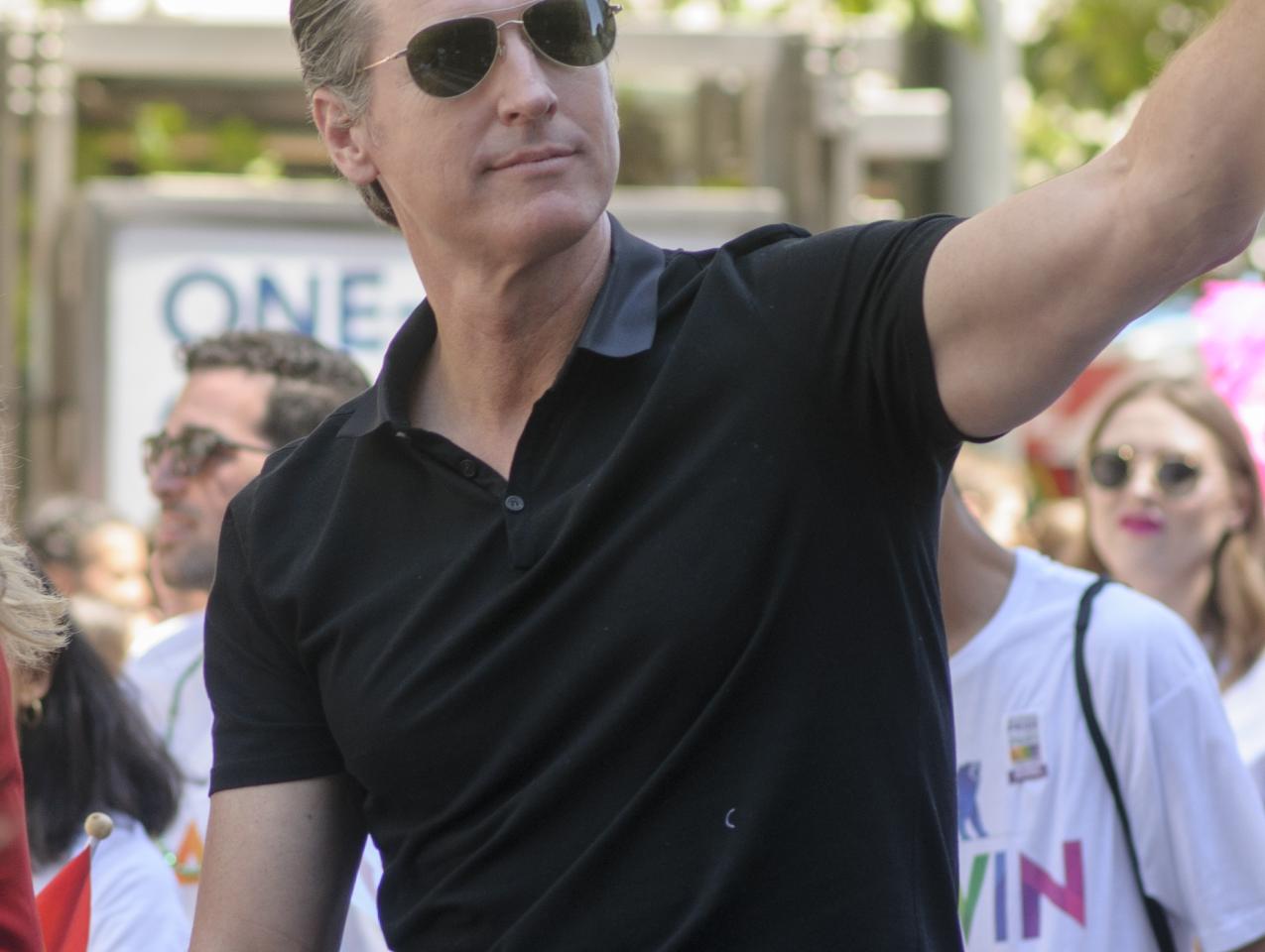

The 2024 race for the White House could turn out the same, if the media continue to salivate for an encounter between California governor Gavin Newsom and Florida governor Ron DeSantis—that yearning reaching a new level of Pavlovian slaver after Newsom ran this campaign-paid ad in Florida (you read that right) over the Fourth of July holiday taking DeSantis and his red-state sensibilities to task, with Florida’s governor responding in kind at a press conference a few days later (“California is driving people away with their terrible governance,” DeSantis told reporters. “They are hemorrhaging population. It’s almost hard to drive people out of a place like California given their natural advantages, yet they’re finding a way to do it.”)

How could we not end up with a Newsom–DeSantis showdown? Either governor could decide the timing’s not right for a presidential bid (time would seem to be on DeSantis’s side, given that he turns 44 in September). Both would have to figure how to circumnavigate intraparty roadblocks. DeSantis might have to contend with fellow Floridian Donald Trump, the Republican nominee in 2016 and 2020. Newsom might face multiple impediments, beginning with an incumbent Democratic president who or may not seek a second term, plus how California’s governor would finesse his away around the Democratic vice president, who by the way just happens to be a fellow Californian.

But what if we do end up with a Newsom–DeSantis matchup two summers from now? Welcome to a comparison between the Golden State and the Sunshine State.

That begins with a look at respective economic clout. California’s GDP in 2021 was $3.35 trillion, representing roughly one-seventh of the overall US economy. If California were a nation, it would boast the world’s fifth-largest economy, trailing America, China, Japan, and Germany.

Not that Florida, with a $1.2 trillion gross state product, is an economic slouch. If it were an independent country, Florida would be the home to the world’s 15th-largest economy (in the past year, the Sunshine State surpassed Indonesia’s and Mexico’s economies).

And if the two states’ economic conditions remain unchanged over the next two years, both governors could brag about revenue galore in their respective state coffers. Florida posted a record $21.8 billion surplus in the fiscal year that ended June 30. And California? The Golden State’s record operating surplus was a record $97.5 billion (yet apparently there isn’t cash available to fully repay the federal government for money borrowed during the pandemic to fund unemployment benefits).

Otherwise, sizing up Newsom and DeSantis—and, for that matter, California and Florida—isn’t the same as comparing oranges and oranges, even for two citrus-centric states.

DeSantis acknowledged as much in bringing up demographics. California lost a little over 117,500 residents in 2021, putting its population at a shade under 39.2 million. Florida’s population grew by 211,000 between July 2020 and July 2021. Per US Census data, four of the nation’s top-ten metro areas with the highest population growth were in Florida—more than in any other state.

Another key point of departure between California and Florida: public education.

Report Card on American Education gives Florida’s schools an overall grade of a B+ (second only to Arizona). California received a C, placing it 25th among all states. The differences: Florida got an A for school choice, to California’s F; California received Ds for digital learning and teacher quality, to Florida’s A- and B+ ratings. Remember those latter two grades the next time Newsom and DeSantis spar over COVID policy and school closures.

And there’s one difference the media may choose to exploit: style and presentation.

If so, that does not work to Newsom’s long-term political benefit, as we saw in last week’s dust-up between Newsom staffers and the State Capitol press corps over the governor’s family vacation in Montana.

At first, the focus was on hypocrisy: Newsom, always the red-state critic, engaging in a little R&R in one of America’s more conservative bastions (Democrats have won only two of Montana’s last 16 statewide contests). Complicating matters: Montana is on California’s list of places state employees are banned from visiting (for official business) due to its LGBTQ policies (Montana made the list last year for enacting a state law banning transgender females from participating in girls’ school sports).

Newsom staffers pushed back against the bad press by insisting that the travel ban didn’t apply to Newsom—a family vacation not the same as official state travel (the governor’s office also mocked the reporter who broke the news, which is never a good look for a political communications operation).

But that didn’t change one other problem: Newsom’s office seemingly tried to hide the governor’s whereabouts—perhaps knowing the travel ban would come into play—by putting out a statement on July 1 merely stating: “Governor Newsom has left the state.”

That wasn’t the case with past gubernatorial travel: the governor’s office detailed earlier this year, with specific dates, the Newsom family’s journey to Central and South America; and, last Thanksgiving, announced that the First Family would be in Mexico over the holiday.

I mention this because the Montana flap, minor thought if may be on the scale of political transgressions, speaks to two Newsom defects: his actions not agreeing with his rhetoric; and an aversion to being fully candid when first confronted with an apparently hypocritical deed.

Such was the case with Newsom’s handling of the infamous French Laundry dinner back in November 2020—a trifecta of hypocrisy in that Newsom (a) was caught red-handed attending a dinner at a swank restaurant while at the same telling Californians to avoid social gatherings; (b) he dined indoors, despite a spokesman saying it was an outdoor gathering; and (c) the governor was caught on camera dining without a mask, also stepping on his cautionary messaging.

That was followed a few months later by Newsom’s telling CNN he’s “been living through Zoom school and all the challenges related to it” and, during his State of the State address, inferring that he was helping his children to cope with distance learning. The problem with such pathos: the governor’s progeny were attending a Sacramento private school that offered in-class learning.

If presidential politics has taught us anything in the modern era, it’s that candidates can survive—even thriv—despite such blatant character flaws. Just ask Bill Clinton and Donald Trump.

But for Newsom, it’s potentially a major liability as piety, not progress, is his Golden State brand (the final words in his Florida ad: “Join us in California, where we still believe in freedom”). Or, as Newsom recently told CNN in contrasting himself to DeSantis: “He's running for president. I care about people. I don't like people being treated as less of them. I don't like people being told they're not worthy. I don't like people being used as political pawns. This is not just about him, but he is the poster child of it.”

“We're as different,” Newsom added, “as daylight and darkness.”

If only that “daylight” also applied to how California’s governor approaches his job —and his candor in dealing with the media.