- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Middle East

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- US Foreign Policy

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

The Biden administration is taking steps to restore the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or the JCPOA, and lift sanctions imposed by the Trump administration that are inconsistent with the accord. The new administration also assumes that a resurrected JCPOA will be the basis for future agreements to address other areas of concern, including Iran’s ballistic missile program and actions through its proxies that destabilize the Middle East. This initiative raises several important questions: First, what does Iran want? Second, does the United States have the credibility to broker a deal? And third, will a deal help or hurt Middle East stability?

What does Iran want?

Iran wants to have substantial influence in the region to which it belongs. Such a goal is natural and is not necessarily part any specific ideology or strategy. Iran is one of the most important states in the Middle East. This goal is independent of the political character of the current regime or any future regime. Furthermore, the same goal and thinking would apply regardless of who runs Iran. Iran competes with other states in the region for influence and as in other regions, competition involves interests that sometimes conflict, and sometimes converge with those of its neighbors. Like all states, Iran reacts to what it sees as threats and tries to counter those threats. In this respect, its posture is rather ordinary because such behavior is consistent with that of other nation-states.

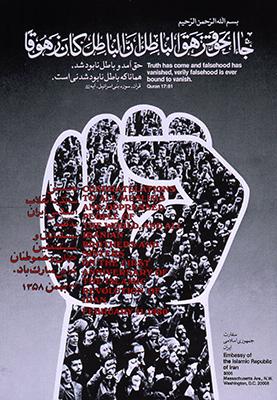

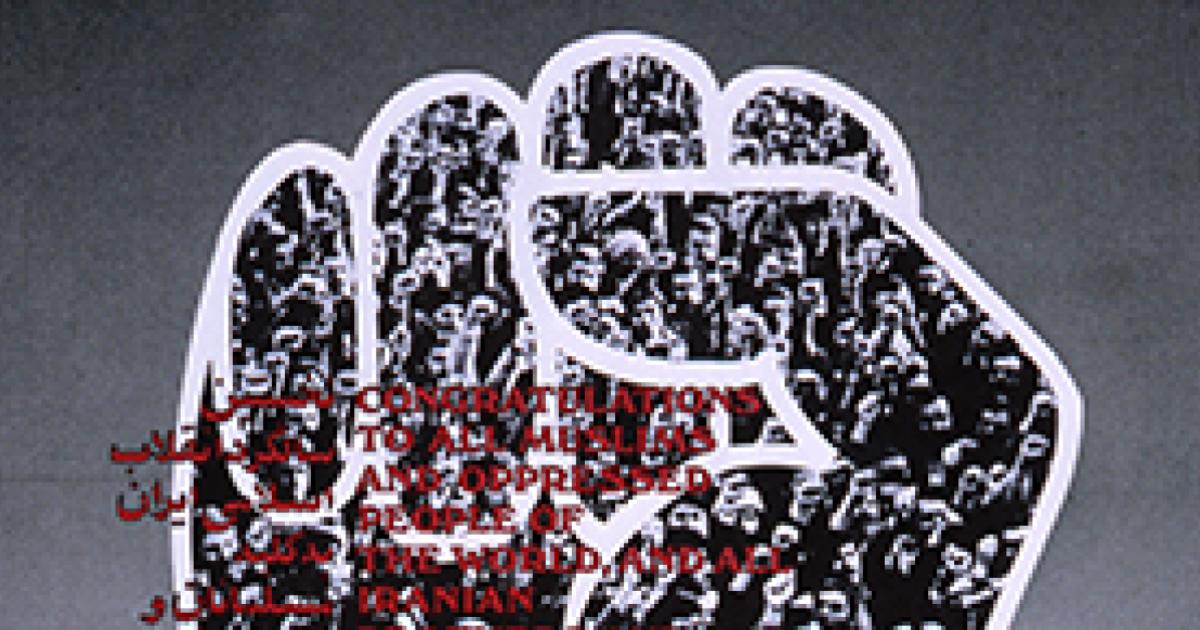

In its quest for influence, Iran faces the disadvantage of being a minority in its own region. It is predominantly a Persian state in a neighborhood that is mostly Arab. It is also mostly Shia in a region in which most people are Sunni Muslims. Some influential religious Sunnis consider Shia barely tolerable. These circumstances contribute to Iran’s sense of being threatened within their own neighborhood. No experience has contributed more to Iranian leaders’ sense of being surrounded than the Iran–Iraq War in the 1980s. The long conflict was enormously costly with hundreds of thousands of casualties. Although Iraq started the war, most Arab states, including those facing Iran across the Persian Gulf, sided with Iraq. Iranians also remember that the United States took Saddam’s side. This experience shaped how Iranian leaders think today and perhaps explains their desire to develop nuclear weapons and undermine U.S. presence in the region. As a result, Iran’s strategic position and sensitivity towards security is arguably, quite rational.

One can easily argue that Iranian policies have been reactions to someone else’s unfriendly actions. For example, Iran’s support of Hezbollah was in response to Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982. When the United States convened a conference in 1991 to address Middle Eastern issues, forty-three states attended, but Iran was excluded from the invitation list. Tehran’s response was to organize a counter-conference to adopt a more militant position toward Israel. Including Iran in the original conference would have likely precluded this response. Additionally, Iran did not start the wars in Iraq, Syria, or Yemen. It did not start the earlier war in Lebanon. It had nothing to do with the war that led to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory. It had nothing to do with the reaction to the Arab Spring in Egypt that established a new repressive regime with destabilizing effects in the form of increased extremist violence. Claims that Iranian actions are the primary cause of instability in the Middle East or that Iran has a goal to dominate the region is inconsistent with the facts. This history is part of a larger picture, as Iranians see it, of hostile powers exploiting local circumstances to threaten Iran. The Trump administration’s U.S.-Israeli-Saudi axis was the latest chapter in that history.

Does the United States have the credibility to broker a deal?

President Biden asserted throughout the 2020 campaign that under his leadership the United States would be “back at the head of the table.” This notion reveals how detached from reality Washington has become. Washington’s track record over the past two decades reveals incompetence rather than the indispensable nation of the past. A series of disasters starting with the 2003 invasion of Iraq and the subsequent destabilization of the Middle East, the ineffectual war in Afghanistan, incoherent policy in Syria, and even domestic failure surrounding the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic show a stunning lack of American leadership. Former President Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, a deal that had been carefully put together by Iran, the United States, five other major nations, and the European Union, further eroded America’s reputation. Trump’s “America First” nationalism damaged U.S. credibility overseas and damaged long-standing alliances.

More importantly, America’s self-immolation domestically projects chaos, polarization, and dysfunction. American culture, shaped by the principles enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, was a cornerstone of American power. By the beginning of the 21st century, race and ethnicity were mostly in the background as defining characteristics of what it meant to be an American. Freedom and equality under the law, though imperfect, was a reality. Two centuries of progress towards creating a more perfect union began to fray during the Obama administration when race was again brought to the forefront. It was divisive and continued under Trump and has accelerated under the Biden administration. The narrative that the United States is a racist nation, and its institutions are purveyors of systemic racism is dishonest. The message being sent is that the bright glow from the shining city on the hill has dimmed. In such an environment everything Washington hopes to achieve on the foreign stage will be more difficult.

As a thought experiment, let us assume that the United States has the credibility to broker a deal. What would the deal, or the series of deals, entail? Since returning to the provisions of the JCPOA is currently being considered, what exactly does that mean? All constraints effecting Iran’s nuclear programs phase out in 10-15 years under the 2015 agreement. We are well into this timeline. Plus, Iran has been enriching uranium to high concentrations since the United States withdrew from the agreement. Facility inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency have ceased leaving the United States blind as to how far Iran has advanced towards having a nuclear weapon. Most importantly, any deal would require the lifting of the most significant economic sanctions—on the Central Bank of Iran and on oil sales. Once lifted, how would the Administration induce Iran to negotiate a stronger agreement, much less negotiate follow-on agreements to cover other areas of concern? Finally, any deal would be vigorously opposed by Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Military hardware, as a form of inducement to go along, would likely be used against Iran and its proxies undermining any benefit of a renewed JCPOA. The problems associated with going back to the JCPOA are obvious.

Will a deal help or hurt Middle East stability?

It is unlikely that a return to the JCPOA will benefit regional stability in the long term. The return would compound the error of the Obama administration of having a JCPOA policy instead of an Iran policy. Washington must reconsider how its interests are affected by Iranian actions in the Middle East and move beyond emotions that are a legacy of the 1979 hostage crisis. Much of today’s U.S. policy toward an entire region is built narrowly around containing Iran.

In the past, ensuring the flow of oil for U.S. consumers, supporting Israel, fighting terrorists, and preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction were goals Americans supported. These goals are less critical today and sacrificing American lives to obtain these goals is not likely. The United States is energy independent; Israel’s strategic position has never been stronger; terrorism no longer holds the importance it once did largely due to U.S. and allied actions against terrorists over the last two decades. Lastly, actions to curtail Iran’s quest for nuclear weapons have been unsuccessful. A different approach will be needed.

If the biggest U.S. interest in the region is to keep Iran from becoming a hegemon over the Middle East, she need not worry. Iran lacks the hard power to come anywhere close to hegemony. Its military spending is dwarfed by that of Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Israel. These countries possess modern equipment and have demonstrated the capacity to effectively use their weapons systems. Iran relies on obsolete military hardware. Besides the military balance, the region’s ethnic and religious geography also works to Iran’s disadvantage. There is no need to worry about Iranian hegemonic desires.

What about the link between U.S. interests and Iranian activity in Syria and Iraq? Iran has had close relations with Syria for decades. What difference does it make to U.S. interests that Iran has been supporting the Assad regime against ISIS and other threats, given that the U.S. lived with the Assads for nearly five decades? Nothing in the Iranian-Syrian relationship has increased the threat to the U.S. In Iraq, Iran is using its influence to help eliminate ISIS, as well as bolstering the Iraqi regime and, in the longer term, avoiding another Iran–Iraq War.

Iran still has the capacity to challenge its enemies and shows a willingness to do so. The Iranians have not backed down in the face of U.S. pressure. Iran wants the U.S. to leave the Middle East. This has been a stated goal for decades. Accordingly, Iran will continue to attack, indirectly, U.S. personnel and bases in a measured way. The “War of the Flea” against the U.S. will accelerate because of the successful drone strike that killed General Soleimani. The United States will not be able to completely deter Iranian action. Washington lacks coercive credibility and political dysfunction in Washington will undermine effective deterrence. Given this reality, Washington should consider a different tact.

Continuing to treat Iran as an incurable foe risks creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. The United States needs to better understand Iranian actions to determine what incentives might influence future Iranian decisions. Rather than focus on how to use force to deter, Washington needs to signal how Tehran could benefit from cooperation. Certainly, some type of nuclear deal for sanctions relief is necessary as a starting point. A resolution of the nuclear issue could help ease tensions between Iran and Israel, as well as with U.S. Sunni Arab allies such as Saudi Arabia who fear the possibility of Shiite Iran obtaining nuclear weapons.

While Washington needs to pursue direct, bilateral negotiations with Iran, any negotiations with Tehran must ultimately involve diplomatic engagement with all states of the Middle East in pursuit of greater stability and prosperity. The diplomacy should recognize that all states have some interests that conflict, and others that converge with those of the United States. Any formula needs to meet reasonable and legitimate requirements of all players, including Israel. In fact, the least important player may be the United States. The concerns and interests of the regional states must take precedence, whether America likes it or not.

To conclude, the United States will not fight a war in Iran. Sanctions impose a cost on Tehran but have a poor track record in shaping Iranian behavior on its nuclear program and its regional policies. Furthermore, America’s coercive capability and credibility are insufficient to dissuade Iran’s own coercive actions. The absence of formal diplomatic ties must end otherwise Iran will continue to strengthen its ties with Russia and China to counter American actions. The United States must stop looking back and recognize Iran’s legitimate interests in the region to which it belongs. Working with our enemies can be just as important as working with our friends, especially when reducing the spread of nuclear weapons is involved.