- History

- Military

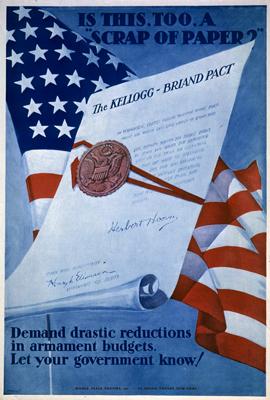

Arms control agreements have become an accepted part of the diplomat’s toolkit. They’re taught in seminars at places like Johns Hopkins’ SAIS and Harvard’s Kennedy School; they’re name-checked alongside peace treaties and trade agreements as things diplomats do; negotiating and monitoring them is even a career track. And yet in their current form, they have a very short—and even more checkered—history. The truth is, for someone looking for past examples of how arms control treaties, such as the Iran nuclear agreement, might work in the present, history provides only a handful of directly analogous examples.

Of these, not many are promising. As my colleague Adam Garfinkle, the Editor of The American Interest (and former speechwriter to Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice) has written before: “No arms control agreement can achieve within the four corners of a document what the parties are unwilling to achieve outside of them. An arms control agreement can ratify, and perhaps stabilize, strategic reality; it cannot create it.”

The history of arms control offers some useful if not reassuring examples. The Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) have been observed when they don’t matter (decades of successfully restraining Paraguay’s nuclear program!) and honored in the breach when they do (North Korea). Israel, a state which has never joined the NPT, stopped dangerous programs in Syria and Iraq by direct action—and for its pains was denounced as a lawbreaker by many NPT signatories whose inaction would have allowed these two states to develop and deploy nuclear weapons.

One of the most successful arms control treaties of the modern era was the Washington Naval Treaty (WNT), which limited dreadnought construction to fixed quotas among the major powers after World War I. Often seen as emblematic of the West’s unrealistic pacifism in the wake of the War to End Wars, the WNT was actually a U.S. policy success, allowing Washington to maintain parity with the United Kingdom, stay ahead of all other rivals and save money in the process. Moreover, at the time, anything that reduced the naval power of potentially hostile countries tended to privilege American security. Yet even this agreement had flaws. The Washington Naval Treaty did not solve our security problems between the two world wars, and by creating an illusion of safety it may have made World War II more likely.

What insight do past efforts offer for the current agreement between Iran and the P5+1 powers? There are two points worth bearing in mind. The first is that the deal is ultimately only as strong as the commitment of both parties to it. Both parties are free to walk away from the agreement, and Iran has the additional option of attempting to cheat. Iran had already signed the NPT; that an additional agreement was required illustrates the limits on treaties to block nuclear programs by determined states.

The second point is that successful arms control treaties tend to arise out of a favorable geopolitical balance. The United States entered the Washington Naval Conference from a position of great strength, and was able to achieve virtually all of its goals in the ensuing talks. Similarly, the fall of the Soviet Union ushered in a period of very successful arms control agreements. The Americans didn’t want an arms race, and the Russians couldn’t afford one.

It is here that the disjuncture between American policy and the kind of policy most likely to result in strong and durable arms control agreements becomes troubling. The Obama administration had an historic opportunity to create such a situation when a Sunni rebellion against the Assad dictatorship swept across Syria. The destruction of Iran’s client regime in Damascus would have broken the land route from Iran and Iraq into Lebanon. That, plus the loss of the protection of Assad’s Syria, would have weakened Hezbollah considerably and strengthened the hand of more moderate groups in Lebanon.

By failing to capitalize on the opportunity in Syria (instead diverting U.S. political and military power to the tragically ill-considered adventure in Libya, an adventure whose adverse consequences have created a continuing humanitarian disaster and security threat in and around that country), the Obama administration gave the impression to Iran and its neighbors that the United States was determined to exit the Middle East under virtually any conditions. This perspective shaped Iran’s approach to the negotiation, encouraging those who urged the negotiating team to resist western demands, and providing ammunition for the argument that the Obama administration was desperate for almost any deal and would accept almost any terms.

The same perception undermined the confidence of longtime American allies in the region, contributing to a much more violent and unsteady atmosphere in a part of the world that the United States would normally be trying to destabilize. The tragedy is still playing out; the costs will continue to mount.

These are not the conditions that successful arms control treaties need to endure. The United States now faces a choice. It can undertake a strong program of containing Iran in the region, an approach that would entail an aggressive approach to monitoring treaty compliance and punishing breaches, or it can continue the current policy of accommodating Iran and hoping that as Iran’s power grows, its political ideas will mellow.

If, as seems likely, the Obama administration stays on the second course of action, the growing geopolitical instability in the region is likely to undermine the nuclear agreement as well.