- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Military

- History

The case for Barack Obama’s foreign policy is as follows: He inherited a catastrophic world of woe from his predecessor, including two foreign wars, an aggressive Al-Qaeda, a deep mistrust of the United States abroad, and a shaken economy at home. Today, the woe is waning: troops are home from Iraq and gradually but inexorably coming home from Afghanistan; Osama bin Laden and twenty of his top comrades are dead; America is more popular overseas; diplomatic initiatives have reduced nuclear weapons and tightened sanctions on Iran; and the economy is slowly struggling back. The nation has turned the corner.

The case against Obama’s foreign policy paints a different picture: He has alienated key American allies. He has achieved only modest returns from outreach to Russia, China, Iran, and the Muslim world. He has stalled the American economic recovery and embraced an image of the United States as a declining power. Meanwhile, Russia expands its influence in Georgia, Ukraine, and Central Asia. China coddles an increasingly erratic North Korea and threatens Asian sea-lanes. Iran draws closer to acquiring nuclear weapons. And the Arab spring may become a Muslim winter if Islamist governments tilt the balance against moderate Arab states and sever peace agreements with Israel. In short, war clouds may be gathering, especially in the Persian Gulf.

Which case is correct?

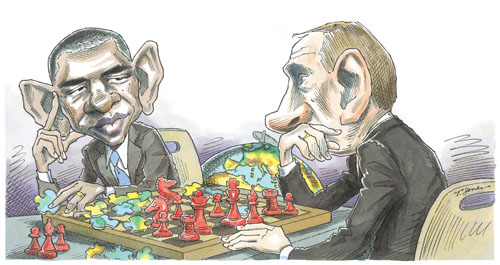

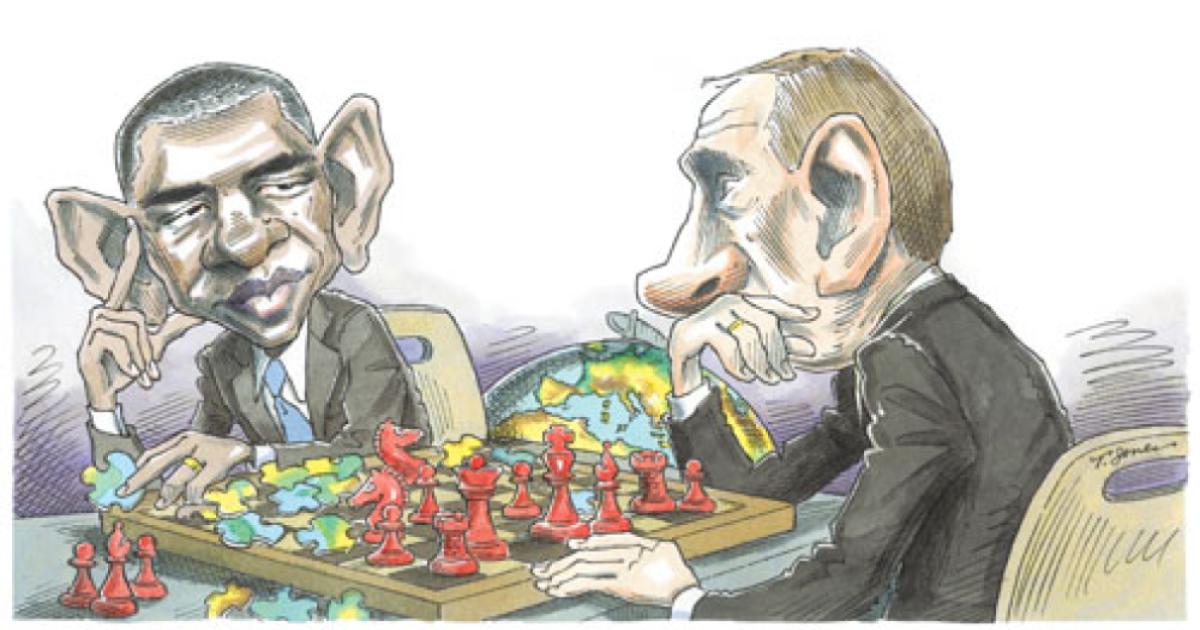

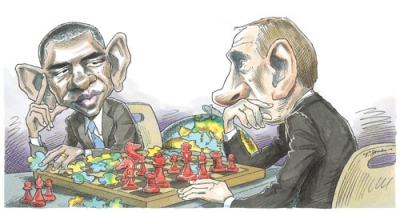

If world politics is like a big jigsaw puzzle in which many countries have to solve many problems cooperatively—not competitively—before the final picture falls into place, then Obama’s record looks quite good. He has downplayed differences of ideology and power that divide countries, defined problems of common interest, rallied multilateral institutions to the task, and put some pieces into place, such as the New START treaty with Russia and further rounds of sanctions against Iran.

On the other hand, if the world works more like a chess match than a jigsaw puzzle, Obama’s record is troubling. In a game of chess, players seek to win, not cooperate; to checkmate and defeat one another, not to address common agendas. In this world, Russia moves its pawns permanently into Georgia, checkmates the orange revolution in Ukraine, and stalks what it calls “a sphere of privileged interest” in the former Soviet space. China revs up its economy, to some extent at the expense of the world economy, and extends its “core” interests to resource-rich islands in the South and East China Seas. Iran dismisses Obama’s open hand and, with Russian help, arms clients in Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and (increasingly) Iraq. North Korea attacks its neighbors, and China supports a besieged Pakistan as the United States withdraws from Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda may be on the run, but its backers—failed, rogue, and authoritarian states—may be on the rise.

Which way does the world work? At times it works both ways. After World War II, the European countries abandoned centuries of chessboard conflict to put together the jigsaw puzzle of the European Union and, with the United States, the NATO alliance. At the same time, the United States, Europe, and Japan played chess to mobilize countervailing alliances, checkmate, and ultimately defeat the Soviet Union.

Successful presidents have integrated the two approaches. Will the next American president get the mix right?

THE JIGSAW PUZZLE

Four propositions define a jigsaw-puzzle view of the world.

First, problems in the world are created by material circumstances, by resource shortages and institutional deficiencies, not by moral or political conflicts. Countries must face and solve these problems together regardless of their cultural, religious, or ideological makeup. Material problems create practical opportunities that override political differences. Obama has identified four material problems that the world must confront and solve together: proliferation of nuclear weapons and materials threatening and inciting violence; the promotion of peace and security, primarily through multilateral institutions; the management of global resources and the preservation of our planet; and the revival of the global economy that alleviates poverty and dispels oppression.

The second feature of the jigsaw-puzzle view is that the material problems of the world are connected and must be solved simultaneously. Because the problems are interwoven, there are no priorities among them. A puzzle comes together only if the players consider all the pieces concurrently, separating them out into those that go on the edge of the puzzle, those that have the same color, and so on. If players select some pieces as priorities and those pieces don’t fit the parts they have already assembled, then they cannot complete the puzzle. So, in a jigsaw-puzzle view of the world, all problems become priorities. In his first three years in office, Obama addressed every conceivable foreign-policy crisis on the globe. He rarely told us which problems deserved particular attention. A puzzle-solver reacts to problems. He does not define them.

The third feature of a jigsaw-puzzle view of the world is that all countries share interests in the problems and therefore must be at the table to solve them. Multilateralism is the bumper sticker of Obama’s foreign policy. Shared interests trump sovereign interests. Thus the United Nations is the principal forum for dealing with Iran, the G-20 for the global economy, NATO for Libya, the Arab League for Syria, and nuclear summits for nonproliferation. One of Obama’s own staff members referred to this as “leading from behind.” The United States remains a catalyst for global action but fades to the background, encouraging other countries to take the lead.

The fourth and final feature of a jigsaw-puzzle view of the world is that the use of force is a last resort after diplomacy fails. Using force during negotiations breaks up the cooperative game and almost always results in more violence. Players rely on respect to get things done, and threat and intimidation undermine respect. Diplomacy isolates and shames recalcitrant countries to come back into the fold; coercion alienates them.

The jigsaw-puzzle view is coherent. Obama and many others believe it is best suited for a cash-strapped Washington and war-weary America. Obama is patiently isolating the Iranians, passively following the Arab spring in Egypt, calmly waiting for consensus in Syria, hoping to stock up goodwill with Russia and China, and subtly repositioning America to lead from behind. In a jigsaw-puzzle world, time is no constraint because all countries envision the same outcome when the pieces of the puzzle are finally assembled.

THE CHESSBOARD

But what if other countries have aggressive intentions? What if they see the world as a chess match more than a jigsaw puzzle?

In the chessboard view of the world, problems are primarily political, not material. Interests are sovereign, not shared; outcomes are zero-sum (if one side goes up, the other goes down), not congruent; and the use or threat of force is leverage inside and outside negotiations, not a last resort if negotiations fail.

Each nation seeks material gain, to be sure, but it also seeks to live in a world that shares more of its moral standards and solves problems in ways that advance its cultural and political influence. The United States does not feel comfortable in a world of fascist or communist countries, and Russia and China do not feel comfortable in a world of liberal democracies. Thus, while the United States seeks to spread political standards of human rights and the democratic rule of law, Russia and China prefer a world that is more sympathetic to elites and authority. They oppose interventions in sovereign nations, such as Kosovo, Libya, Syria, Iran, and North Korea, designed to advance humanitarian or democratic goals. Playing chess, Russia and China use the existence or implied threat of force to leverage their positions inside as well as outside negotiations.

While jigsaw-puzzle countries play defense, solving problems as they pop up, chess countries play offense, creating problems where their priorities dictate.

Obama is not unaware of the chessboard. He just downplays it, hoping that the jigsaw puzzle will be more seductive. He intervened in Libya for humanitarian, not strategic, reasons. What happens in Libya is far less important to the future of the Middle East than what happens in Egypt, Syria, or Iran. Yet Obama intervened in the geostrategic situation that mattered least.

So far, we know two things about when Obama might use force. He will use it after the United States has been attacked (a “war of necessity,” as he called the war in Afghanistan) but not before, in anticipation or prevention of an attack (a “war of choice,” as he called the war in Iraq). In the first case, he surged troops in Afghanistan and ordered risky raids to kill Osama bin Laden in Pakistan and rescue American hostages in Somalia. In the second case, he used force to prevent genocide in Libya.

But when will he use force before an attack in strategic situations that matter more than the one in Libya? When will he insert or maneuver force to deter rather than defend? He repeatedly says that all options are on the table, but he acts differently.

From now on, terrorist attacks will be met by “offshore” cruise missiles, pilotless drones, and swift special-operations strikes, not boots on the ground as in Iraq and Afghanistan. What if the offshore approach is inadequate over the long run?

The scramble to replace American power may be under way. This could be a dangerous time for the world, reminiscent of the scramble to replace American power after the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam. That withdrawal eventually led to a Soviet naval base in Vietnam and Moscow’s invasion of Afghanistan.

FINDING THE RIGHT MIX

Both the jigsaw puzzle and chessboard views of the world make sense under certain circumstances. Knowing how and when to combine them is the mark of great leadership.

George W. Bush pushed the chessboard view too far. He saw terrorism as a moral struggle, but he failed to complement that view with a timely jigsaw-puzzle strategy. The time for diplomacy was most favorable in the summer of 2003. The successful invasions of both Afghanistan and Iraq gave Washington substantial leverage, despite lingering unhappiness over the war, to structure a broader multilateral approach to peace in both the Middle East and South Asian regions. Bush’s father did exactly that in the Middle East after the successful Persian Gulf War of 1991. He launched the Madrid Conference, which eventually spawned the Oslo accords—a step considered a success at the time. By contrast, Bush the son delayed a peace initiative in the Middle East for four and a half years, finally launching one too late in November 2007, and he neglected nation-building to some degree in Afghanistan while the Taliban regained its footing.

President Obama and President Hu Jintao of China prepare for a working dinner in the White House last year. Beijing’s support for North Korea, its increasing projection of force in regional sea-lanes, and its discomfort with liberal democracies are among the challenges facing American leaders.

Obama’s error, however, may be precisely the opposite. He is overplaying the jigsaw-puzzle view of the world and leaving himself vulnerable if other major countries play chess, as they certainly do. Unlike presidents Truman or Reagan, he does not see that the ambitious diplomacy he favors requires a robust defense budget. He is cutting defense spending by $487 billion over ten years and by an additional $600 billion if Congress cannot reach a budget compromise by the end of this year.

Obama is potentially painting an image of the United States as a paper tiger. Without a greater willingness to integrate the use of force with diplomacy, Obama’s foreign policy is flaccid. In the short run, diplomacy buys time and raises expectations. But in the long run, unless military power cuts off alternatives outside negotiations and invites serious bargaining inside negotiations, diplomacy endangers the cause of freedom—in the streets of Iran and Egypt, the Stalinist bunkers of North Korea, and the prisons of Russia and China.

In his campaign white paper issued in September 2011, Republican nominee Mitt Romney stresses that he sees the world primarily in moral, not material terms. He starts off with American values, then discusses the need to fix the American economy and strengthen the American military. He is not comfortable with the decline of American power. He favors returning to the market-oriented policies of the Reagan era, calling for a Reagan Economic Zone of deepening trade and investment among freedom-loving countries. And he favors expanding the Navy and Air Force and putting an additional aircraft carrier task force in the Middle East.

The principal threats he identifies are the powerful and authoritarian states that stalk the world community. China is first among them, along with the “broad arc” of terrorism extending from Pakistan to Libya. While acknowledging that force is always the least desirable option, he advocates the use of force before, not after, events erupt in an attack on the United States or its allies. He emphasizes the buildup and maneuvering of force before a crisis in order to deter adversaries from attacking in the first place. He stresses allies, such as Europe, Japan, and South Korea, and friends, such as India and Indonesia. He puts less emphasis on multilateral institutions, which he characterizes as “forums for the tantrums of tyrants.”

Romney clearly has more of a chessboard view. His challenge is going to be to complement it with a jigsaw-puzzle approach that justifies the risks posed by the chess match. How does Romney integrate military pressure and diplomatic vision to offer Iran, North Korea, and their benefactors in Moscow and Beijing a way forward in peace and freedom? It’s not easy to come up with such a vision given the ill will in Tehran and Pyongyang and the lack of will in a war-weary America.

In different times, Ronald Reagan found the right mix. He challenged the Soviet Union to a military contest it could not win while offering Moscow a future of economic inclusion it could not resist. And he rallied the American people, politically paralyzed and tired of war, to distinguish between decline and defeatism and to believe in themselves again.

The Obama-Romney contest features a sharp contrast between the chessboard view of the world held by Romney and the jigsaw-puzzle view Obama holds. The challenge for the man who wins the battle will be to find the right mix between the two—because if there isn’t one, our foreign policy will continue to suffer and America’s position in the world will continue to erode.