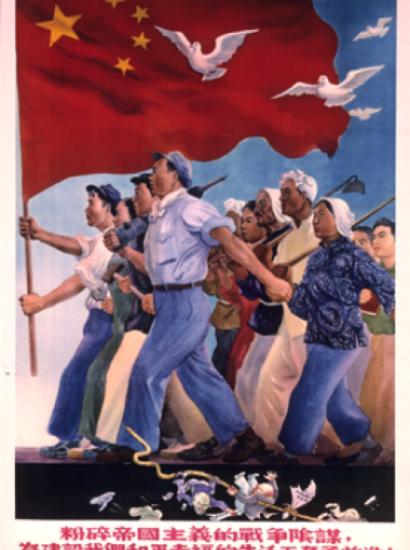

- History

- Military

Last March, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson attempted to set American policy toward China for the next 50 years. Washington in its dealings with the Chinese state, he said, would be guided by the principles of “non-conflict, non-confrontation, mutual respect, and win-win cooperation.”

Nobody wants conflict or confrontation and everyone values respect and seeks cooperation. Tillerson’s statement, however, is misguided, as just about every assumption behind those words is wrong. America, therefore, needs a completely new paradigm for relations with Beijing.

As an initial matter, the phrase Tillerson used is not Washington’s. It’s Beijing’s, and the Chinese consider it the foundation of their “new model of great-power relations.” Their “new model,” in sum, is that the U.S. does not challenge Beijing in Asia. China’s policymakers, therefore, heard America’s chief diplomat promise that the Trump administration would not oppose their attempts to dominate their periphery and the wider region.

Obviously, Tillerson did not think he was agreeing to a Chinese sphere of influence or even to defer to Beijing, but his words show how eager American policymakers are—and have been—to partner with China.

The general thrust of American policy, especially since the end of the Cold War, has been to integrate China into the international system. Washington has employed various formulations, such as Robert Zoellick’s “responsible stakeholder” concept announced in 2005, but the general idea is that Beijing would help America uphold the existing global order. U.S. policy, in many senses, was the grandest wager of our time.

And by now, the bet looks like a mistake history will remember. In short, America’s generous approach has created the one thing Washington had hoped to avoid: an aggressive state redrawing its borders by force, attacking liberal values around the world, and undermining institutions at the heart of the international system.

This decade, China’s external policies, except in the area of climate change, have moved in directions troubling to American leaders. During this time, Beijing has, for instance, permitted Chinese entities to transfer semi-processed fissile material and components to North Korea for its nuclear weapons programs. North Korean missiles are full of Chinese parts and parts sourced through Chinese middlemen. China even looks like it gave Pyongyang the plans for a solid-fuel missile.

China’s leaders have permitted North Korean hackers to permanently base themselves on Chinese soil, where they have launched cyberattacks on the U.S., such as the 2014 assault on Sony Pictures Entertainment. Beijing has itself hacked American institutions such as newspapers, foundations, and advocacy groups, and it has taken for commercial purposes somewhere between $300 billion to $500 billion in intellectual property from American corporates each year.

China violated its September 2015 pledge not to militarize artificial islands in the South China Sea; refused to accept the July 2016 arbitration award in Philippines vs. China; threatened freedom of navigation on numerous occasions with dangerous intercepts of American vessels and aircraft; seized a U.S. Navy drone in international water in the South China Sea; and declared without consultation its East China Sea air-defense identification zone. Its warning to a B-1 bomber in March was phrased in such a way as to be tantamount to a claim of sovereignty to much of the East China Sea. Official state media has issued articles that imply all waters inside the infamous “nine-dash line” in the South China Sea are China’s, “blue national soil” as Beijing now calls it.

Beijing also wants to grab land. It regularly sends its troops deep into Indian-controlled territory with the intention of dismembering that country.

China, under the nationalist Xi Jinping, is engaging in increasingly predatory trade practices with the apparent goal of closing off its market to American and other companies. Of special concern are its Made in China 2025 initiative and the new Cybersecurity Law.

These are not random acts, unrepresentative of the regime’s conduct. They form a pattern of deteriorating behavior over a course of years. And these acts flow from similar ones in preceding decades, suggesting the aggressiveness is not just related to any one Chinese leader.

Americans who seek to “engage” Beijing typically ignore its bad acts or downplay their significance. Tolerance, unfortunately, has over time created perverse incentives. As the Chinese engaged in dangerous behavior, Washington continued to try to work with them. As America continued to work with them, they saw no reason to stop belligerent conduct. Arthur Waldron of the University of Pennsylvania put it this way: “We have taught the Chinese to disregard our warnings.”

Perhaps the clearest example of this dynamic relates to Scarborough Shoal. In early 2012, both Chinese and Philippine vessels swarmed this chain of reefs and rocks, 124 nautical miles from the main Philippine island of Luzon—and 550 nautical miles from the closest Chinese landmass. Washington then brokered a deal for both sides to withdraw their craft. Only Manila complied. China has controlled Scarborough Shoal since then.

To avoid confrontation with Beijing, the Obama administration did nothing to enforce the agreement. What the White House did do, by doing nothing, was empower the most belligerent elements in the Chinese political system by showing everybody else in Beijing that aggression in fact worked.

Feeble policy has had further consequences. The Chinese leadership, emboldened by success, just ramped up attempts to seize more territory, such as Second Thomas Shoal in the South China Sea from the Philippines and the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea from Japan. China, in short, just made the problem bigger. And its ambitions are still expanding. Chinese state institutions, backed by state media, are now laying the groundwork for a sovereignty claim to Okinawa and the rest of the Ryukyu chain.

There are many reasons why Chinese behavior is not conforming to American predictions. “Rising” powers are always assertive, and the turbulence inside Beijing political circles makes it difficult for Chinese leaders to deal with others in good faith. A discussion of these and other trends is far beyond the scope of this short essay, but it is clear that the U.S. needs to change its China policy now.

So how should policy change?

First, American leaders need to see things clearly. Confucius called it “the rectification of names.” As we take the advice of the old sage, we should not call China a friend or partner. It is a threat, fast becoming an adversary of the sort America faced in the Cold War.

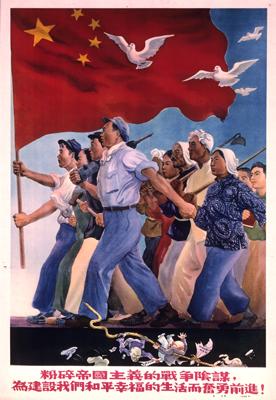

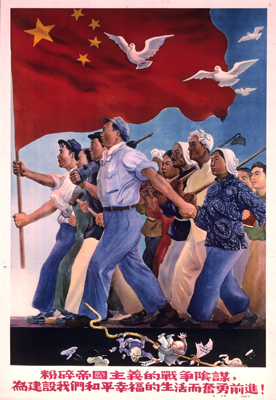

In that multi-decade contest, an authoritarian state sought to spread ideology, remake the international system, and undermine Western values. China is doing all these things, plus trying to redraw its borders by force. Washington needs to realize America is in the midst of an across-the-board struggle with China.

“If you treat China as an enemy, it will become one,” American policymakers were constantly told and then said themselves. Washington treated China as a friend, and it is now becoming an enemy anyway.

Second, Washington must begin imposing costs on China for hostile and unacceptable conduct. Why would Beijing ever stop if it is allowed to keep the benefits of its actions?

Take the example of Chinese banks helping North Korea launder money in violation of U.S. law. Last September, the Obama administration did not sanction these financial institutions when it seized money they held in 25 accounts of Chinese parties that were themselves sanctioned for laundering North Korean cash. Apparently, the administration, by not going after the banks that time, wanted to send a message to Beijing to stop storing Pyongyang’s cash.

Yet Chinese officials surely took away the opposite message. As the Wall Street Journal in an editorial correctly pointed out, Washington signaled that the unsanctioned Chinese banks were “untouchable.”

These financial institutions have long thought they are above the law. Last month, the same paper reported that Federal prosecutors are now investigating whether certain Chinese middlemen helped North Korea “orchestrate the theft” of $81 million from the central bank of Bangladesh from its account at the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

If such middlemen were involved, Chinese financial institutions were almost certainly complicit. If such institutions were complicit, the U.S. should cut them off from their dollar accounts in New York.

Such an action would rock global markets, but it would for the first time in decades tell Beijing that Washington was serious about North Korea—and it would cripple Pyongyang’s nuclear proliferation activities. In any event, the Trump administration has an obligation to enforce U.S. law and defend the integrity of its financial system.

The Chinese economy is fragile at the moment, so Washington, in all probability, would only have to do this once before Beijing got the message and withdrew its support for the North’s various criminal activities.

Imposing costs on China will undoubtedly cost us as well, but we are far beyond the point where there are risk-free, painless solutions. The costs we will bear are the price for relentlessly pursuing overly optimistic—and sometimes weak—policies over the course of at least two decades.

Third, Washington should take the advice of Taro Aso when in late 2006 he proposed an “arc of freedom and prosperity” for the region. America should bolster alliances and strengthen ties with friends old and new. Nations in the region, from India in the south to South Korea in the north, realize the dangers of Chinese assertion and are scrambling to build defense links. Those threatened are drawing together, but the one ingredient they need is stout American leadership.

Fourth, American leaders must again believe in American power as a force for good in the world and realize they do not need Chinese permission to act. President Trump took a step in that direction in his Financial Times interview published April 2 when he said that Washington will solve the North Korean problem on its own if China decides not to help.

Chinese leaders need to see that Washington has adopted a fundamentally new approach and is no longer afraid of them. Tillerson then can say things that advance American and regional interests, not undermine them.