- China

- Confronting and Competing with China

The Trump administration has identified global technological leadership as a core element of its “America First” strategy. Within days of assuming office in January 2025, President Trump issued an executive order calling for US artificial intelligence (AI) global dominance. Measures to realize the president’s call to action soon followed: a reduction in regulatory restrictions around AI development and diffusion, support for more fossil fuel and nuclear power generation, the launch of the “Stargate” AI infrastructure initiative, and a commitment to export the US AI tech stack. The White House has also issued additional executive orders to support digital assets and financial technology, as well as drone technology. More technology priorities are in the pipeline.

To compete effectively with China, however, Trump will require a more comprehensive and strategic approach. Chinese President Xi Jinping understands technology as “the cornerstone of a strong nation” and has created a soup-to-nuts innovation and technology playbook designed to realize his vision of China as the world’s “primary center for science and high ground for innovation.” His playbook is built on five core elements: investment, indigenization, insulation, integration, and internationalization. In each of these components, China is either following close on the heels of or leading the United States.

After decades in which China trailed well behind the United States in both government and private sector funding of research and development, it is now expected to surpass the United States in 2026. Xi’s 2025 budget called for an 8.3 percent increase in government spending on science and technology, including a growing percentage dedicated to basic science. As Xi noted in a 2018 speech: “Basic research is the fountainhead of the whole scientific system.” UCSD researcher Jimmy Goodrich argued in a recent China Considered podcast, “China is really almost at a breakout stage of investment in basic science. . . . They’re building twenty new national labs and scientific facilities across the country. . . . It’s like Xi Jinping has a fascination with Journey to the Center of the Earth and every other sci-fi book.”

In contrast, the Trump administration slashed its 2025 proposed research funding for the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, NASA, and the Department of Energy by as much as 56 percent and seeks to cut funding for basic science from $45 billion to $30 billion.

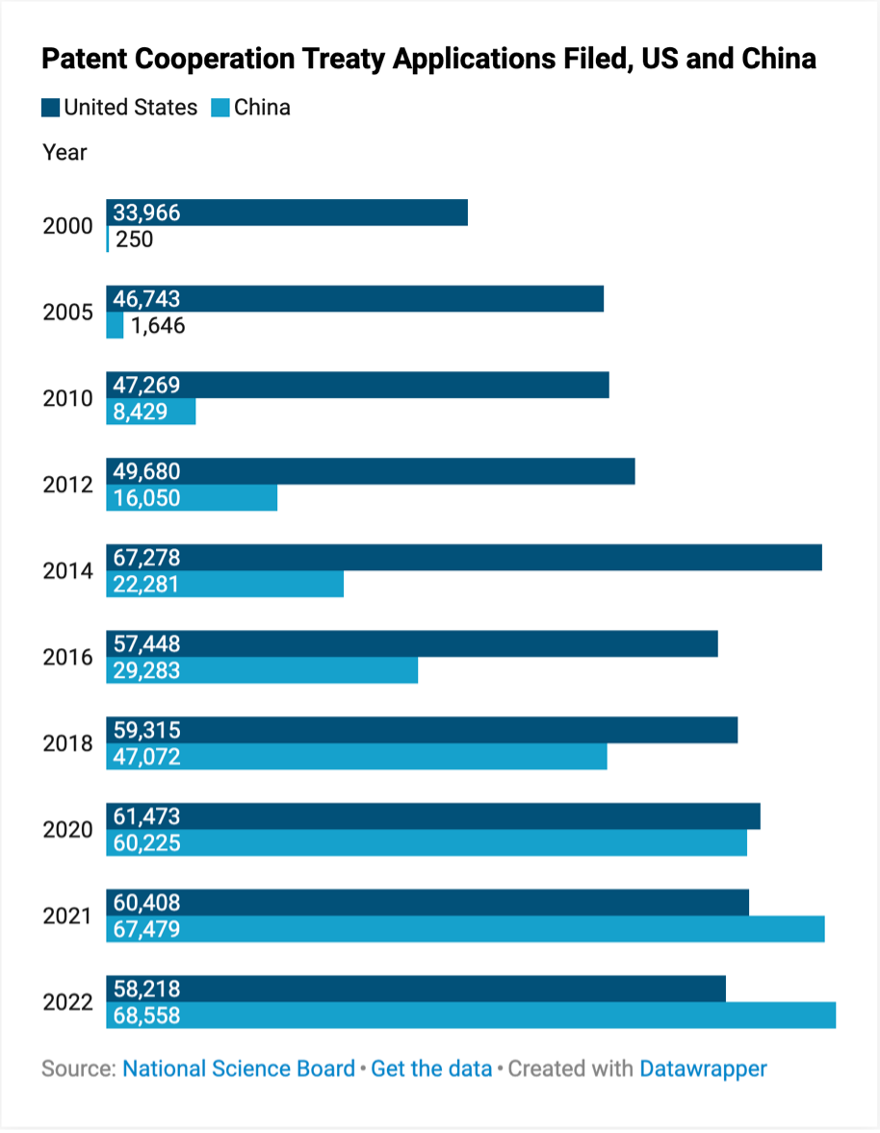

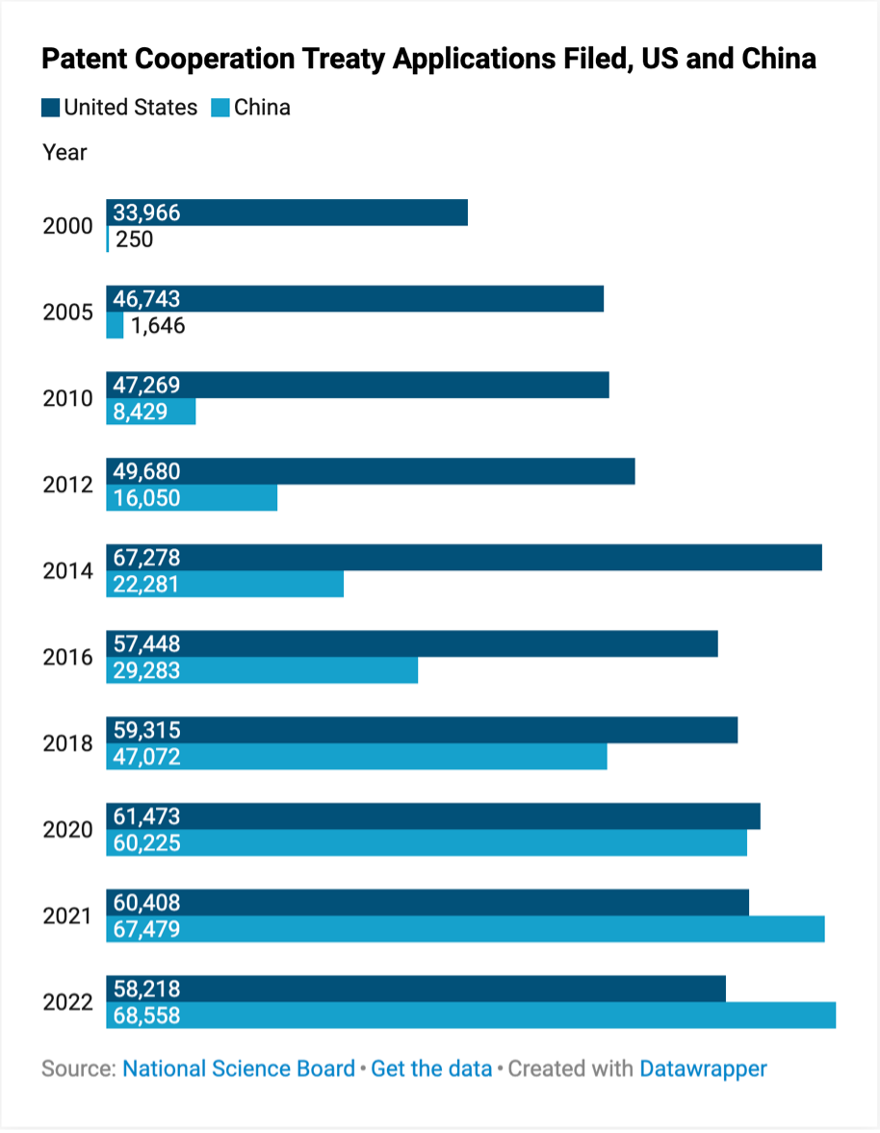

By other metrics, China is already ahead of the United States: It provides 33 percent more contributions to papers in high-quality health sciences and natural-science journals, employs more researchers than the United States and European Union combined, is on track to award twice as many STEM PhDs as the United States, and surpassed the United States in the number of international patents filed in 2019—and the top filer globally was Huawei (see chart). And it continues to invest in its talent base through scores of programs to recruit top scientists from abroad, while the United States is hemorrhaging talent.

In March 2025, the journal Nature reported that of 1,600 scientists polled, 75 percent were considering leaving the United States. The Trump administration’s proposed $100,000 fee on US companies for each H-1B foreign-expert visa may well lead US companies to outsource R&D. A National Academy of Sciences paper further reported that during 2010–21, nearly 12,500 scientists of Chinese descent left the United States for China—more than half during Trump’s first term. And when those scientists leave, they assume leadership positions in the Chinese science-and-technology ecosystem: in 2023, more than 70 percent of university and national project heads in China were returnees.

Moreover, as Hoover scholar Amy Zegart has shown, China no longer has the same reliance on Western training for its top researchers. More than half of breakthrough AI company DeepSeek’s staff is entirely homegrown Chinese talent.

Bringing it home

A second priority for Xi Jinping is ensuring that innovation and the ecosystem supporting it are located inside China. As he said in a 2014 speech before members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Chinese Academy of Engineering, “We cannot always decorate our tomorrows with others’ yesterdays. . . . Moreover, we cannot always trail behind others. We have no choice but to innovate independently.”

Xi’s most significant initiative to advance this objective is Made in China 2025 (MIC2025). The initiative called for 70 percent or more self-sufficiency by 2025 in core basic components and key basic materials in ten priority sectors, such as new materials, medical devices, and semiconductors, and a dominant position in global markets by 2049.

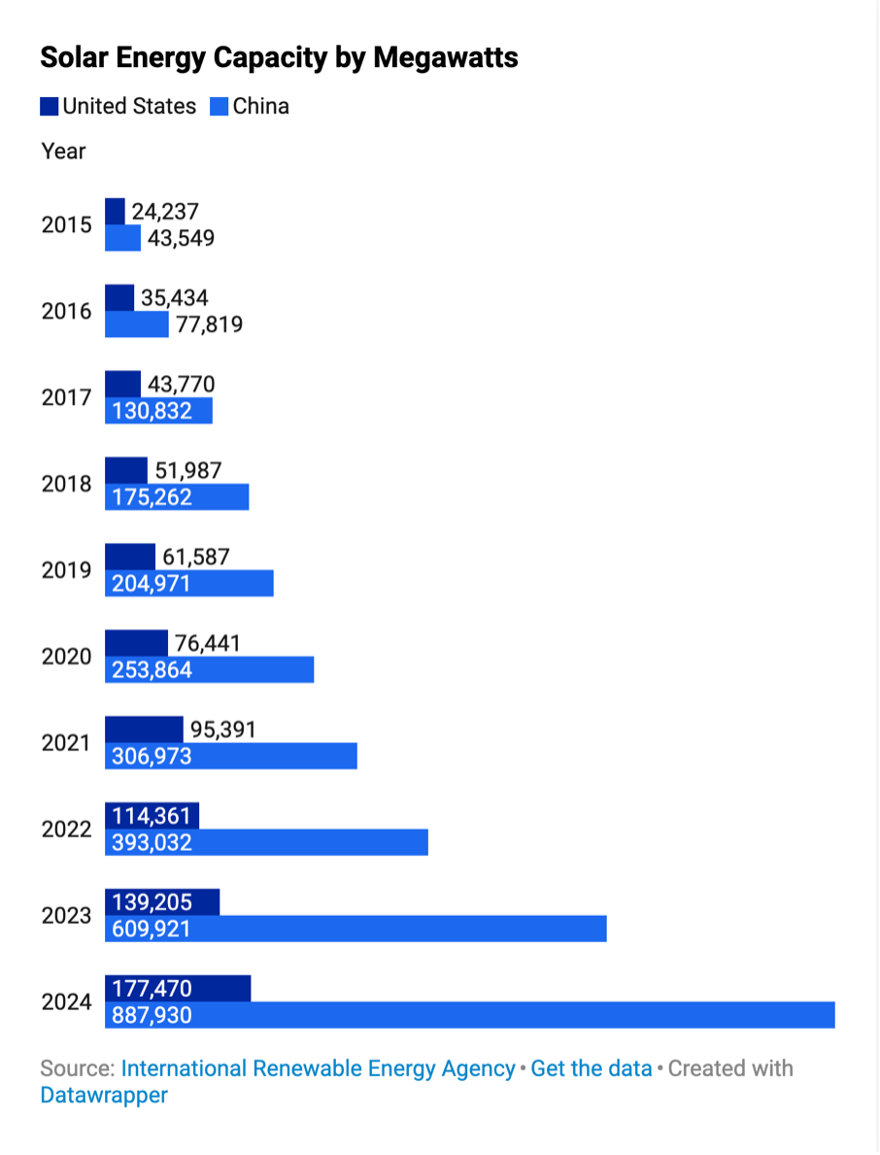

The Rhodium Group reported that Chinese firms took market share from foreign companies in every MIC2025 sector; Bloomberg further assessed that China had achieved global leadership in five technologies within MIC2025 sectors: high-speed rail, graphene, unmanned aerial vehicles, solar panels, and electric vehicles and lithium batteries, while closing the gap in seven others. And as the MIT Technology Review reveals, the gap between China and the United States in these technologies is widening annually. China’s installed solar capacity dwarfs US capacity (see chart). And the same increasingly holds true for other clean-energy technologies, including wind turbines, electric vehicles, and lithium batteries. More than half the cars sold in China are now electric, and Chinese car companies represent two-thirds of global electric car sales.

Closely linked to indigenization is a commitment to insulate Chinese technologies from foreign competition. In pursuing MIC2025, for example, Beijing used an array of market and non-market barriers to help homegrown technologies. For example, MIC2025 required top Chinese hospitals to use 50 percent more domestically produced medical devices by 2020 and 95 percent more by 2030. Methods to realize these goals varied by province: Sichuan forced hospitals to use domestically produced medical devices in fifteen categories or insurance reimbursement would be withheld, while Ningxia required hospitals to justify any foreign medical-device import with an audit. Beijing has continued to reinforce its strategy through additional financial support, procurement policies, regulatory standards, and localization requirements for foreign firms to increase the share of high-end domestically produced medical devices. The objective is a fully homegrown medical device ecosystem from “raw materials to finished goods.”

A similar pattern is emerging in artificial intelligence. Beijing is sharply limiting opportunities for foreign chip companies: it has banned its major technology companies from buying AI chips from Nvidia, instructed Chinese automakers to “avoid foreign semiconductors if at all possible,” required municipal state-owned enterprises to use Chinese-made semiconductors and computing infrastructure by 2027, and mandated that state-owned firms submit quarterly reports tracking their replacement of foreign software with Chinese alternatives.

Chinese skill

The fourth element of Xi’s playbook is the integration of civilian and military R&D via a military-civil fusion program. Although the program was established only in 2017, the practice predates its formal establishment. Huawei, for example, has collaborated with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) since the company’s founding in 1987. Major technology companies will often possess a military-civil fusion department or office whose job it is to facilitate the transfer of commercial technology to the PLA and to signal to companies the technology needs of the military. Alibaba, for example, formed a joint venture with China’s most important state-owned arms designer and manufacturer, Norinco, on a satellite positioning service; Baidu opened a joint laboratory with China Electronics Technology Group, which serves as a critical supplier of advanced electronic systems and components to the Chinese military; and iFlyTek, one of the country’s “AI champions,” has a comprehensive relationship with the PLA and the country’s domestic security apparatus. These direct linkages make for a far more seamless adoption of cutting-edge technologies by the PLA and provide a potential path for sensitive foreign technologies to be surreptitiously exploited by the PLA via a commercial partner.

While Xi is committed to China reducing its reliance on the outside world for core components and materials, he is equally committed to ensuring that the rest of the world relies on Chinese technology. Xi has publicly identified technology as the “main battlefield” in the superpower rivalry and placed a premium on exporting China’s technology stack globally.

Domestically, China leads the world in the scaling and deployment of many technologies, including digital payments, high-speed rail, renewable energy and electric vehicles, e-commerce, and 5G, among others. But it also wants China to be the world’s technology partner of choice. China is investing heavily in global tech infrastructure and in setting global technology standards. Through the Digital Silk Road and Green Silk Road, offshoots of the 2013 Belt and Road initiative, China has become the largest exporter of clean technology globally, and Chinese companies such as Huawei, Alibaba, and State Grid have reportedly invested, loaned, or contracted over $30 billion in overseas telecommunications infrastructure, cloud services, digital payment systems, and satellite navigation platforms to more than 150 Belt and Road countries. China’s BeiDou satellite navigation system now covers 200-plus countries and regions, and more than 130 countries rely primarily on BeiDou rather than GPS for positioning services.

China also seeks to gain advantage for its global technology stack through setting technical standards in international bodies. China now holds top technical leadership posts in the United Nations’ International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and Chinese firms, such as Huawei and ZTE, are among the most active participants in study groups, working parties, and patents. While many of their proposals are designed to secure global markets, some, such as Huawei’s new IP, are designed to enhance state surveillance and control.

A time for new thinking

After more than a decade of implementing Xi Jinping’s innovation playbook, China is in the midst of a technological great leap forward. As UCSD researcher Jimmy Goodrich has noted, “The story of China twenty years ago stealing and replicating technology is really the story of yesterday. We’re looking at a China that is fundamentally changed. . . . So, we have to think about China now as not just a copycat innovator but an original innovator.”

The Trump administration strategy to compete relies on limited government intervention to spur private-sector innovation. But this will not be enough. While the United States does not need to replicate China’s playbook, it needs to understand the challenge it presents to US technology and innovation leadership and respond accordingly.

While US firms remain world leaders in high-impact patents and frontier research, the United States needs to secure the next generation of scientists and engineers who will make breakthrough innovations and lead the commercialization of technology. This means expanding, not cutting or taxing, programs like the NSF graduate research fellowship and H-1B expert visas. One positive step was the intervention by Michael Kratsios, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, to restore five hundred NSF fellowships after the 2025 class had been cut in half from two thousand to one thousand. But more sustained support is needed.

Equally important is investing in basic science. Congress should reverse the Trump reductions in support for the core science agencies and increase funding for the NSF, NIH, DOE, and NASA to support high-risk, high-reward projects. It should further reinstate support for clean energy investments in the United States; otherwise, the administration will have permanently relinquished global leadership and share in a global market estimated to reach $2 trillion by 2035.

Support through public-private partnerships, such as the Biden-era CHIPS and Science Act to bolster advanced semiconductor manufacturing and the Trump administration’s recent Defense Department stake in MP Materials to enhance domestic mining and processing of rare earth elements, are positive examples of how federal support can strengthen US capacity to innovate and manufacture in core technologies. More such programs will be needed in other technologies to compete with China’s state-driven model.

On the global stage, the Trump administration will need to provide robust financial and diplomatic support for American companies seeking to export their technologies to compete with China’s Digital Silk Road. A reported proposal to quadruple the spending power of the Development Finance Corporation would be a welcome first step, but it needs to be coupled with a renewed, robust diplomatic effort. Deploying teams of technical attachés to embassies could help offset the loss of USAID and State Department officials, who traditionally advance US technology abroad.

Building on the work of the first Trump and Biden administrations to promote a “trusted technology” stack with allies and partners—including open standards, certification, training, and finance—would also bolster US companies’ competitiveness.

Without such measures and more robust long-term strategic thinking on issues such as Chinese technology investment in the United States, the role of export controls, and science education, America risks losing the political, economic, and security advantages that accrue to the world’s number one science and technology power.