- Budget & Spending

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- Terrorism

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- The Presidency

- Economics

As the presidential campaign enters its final stages, debate will increase over budget priorities and how to pay for them. Many commentators and political leaders, including the Democratic candidates Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, believe that tax increases are needed to restore near-term budget balance and finance longer-term entitlement growth.

These claims fail budget arithmetic and economics. Worse, they raise serious questions about the nation ’s broad fiscal policies and its commitment to economic growth.

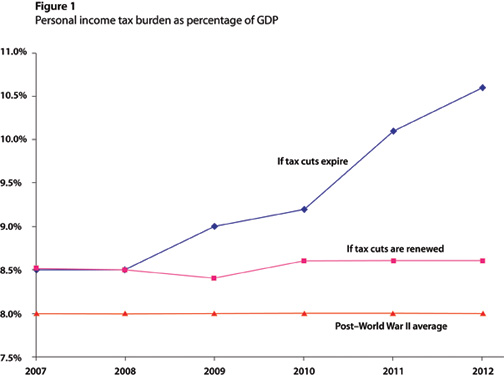

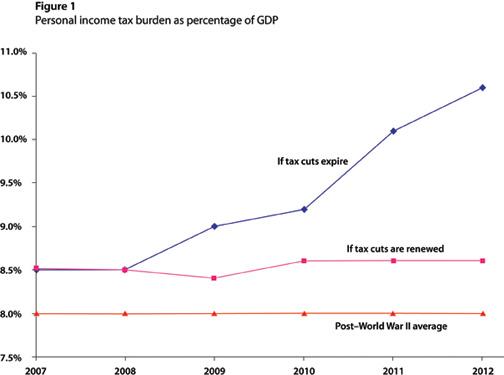

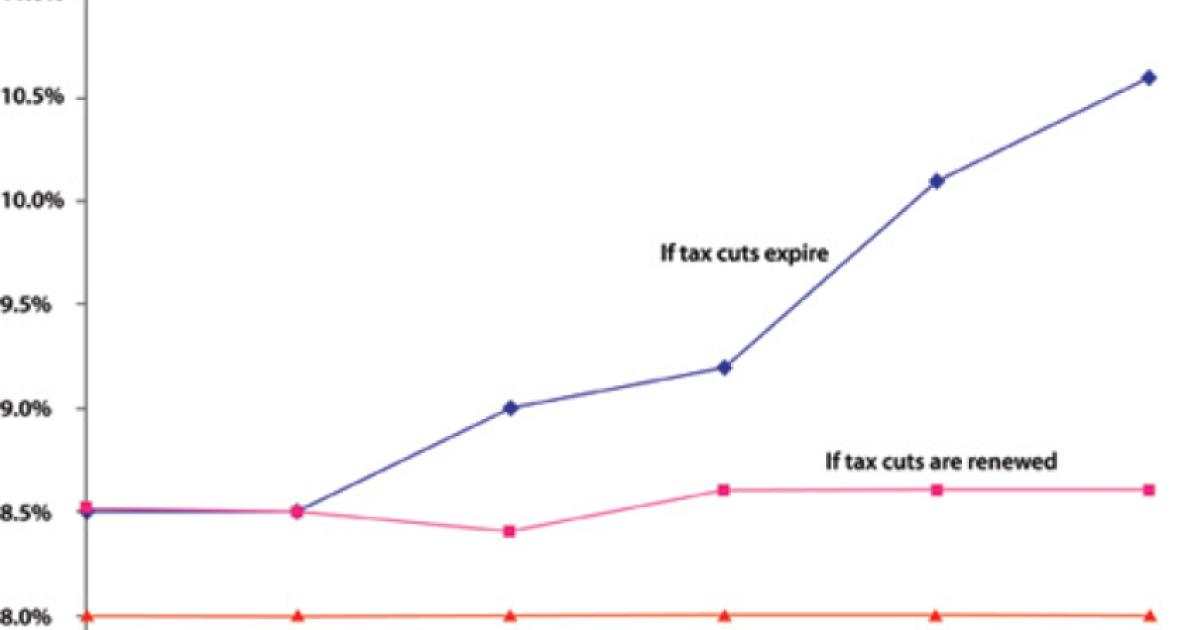

By historical standards, federal revenues relative to gross domestic product, at 18.8 percent last year, are high. In the past 25 years, this level was exceeded only during the 1996 –2000 period. Still, we stand on the verge of a very large tax increase, which will take effect unless the next Congress and president agree to rescind it. Letting the Bush tax cuts expire would drive the personal income tax burden up by 25 percent —its highest point, relative to GDP, in history.

This would be the largest increase in personal income taxes since World War II. It would be more than twice as large as President Lyndon Johnson ’s surcharge to finance the Vietnam War and the War on Poverty. It would be more than twice the combined personal income tax increases under Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton. The increase would push total federal government revenues relative to GDP to 20 percent.

What drives this large tax increase? The tax code changes enacted in 2001 and 2003 are scheduled to expire at the end of 2010. If they do, statutory marginal tax rates will rise across the board, ranging from a 13 percent increase for the highest-income households to a 50 percent increase for lower-income households. The marriage penalty will be reimposed and the child credit cut by $500 per child. The long-term capital-gains tax rate will rise by one-third (to 20 percent from 15 percent), and the top tax rate on dividends will nearly triple (to 39.6 percent from 15 percent). The estate tax will roar back from extinction at the same time, with a top rate of 55 percent and an exempt amount of only $1 million. Finally, the alternative minimum tax will reach far deeper into the middle class, ensnaring 25 million tax filers in its web.

Proponents of bigger government invariably argue that allowing all or some of President Bush ’s tax cuts to expire is necessary in the near term to balance the federal budget and necessary in the long term to finance the retirement and health care promises made to the baby boom generation. But a tax increase is neither wise nor necessary.

As in the past, the economic damage caused by the tax increases and tax-avoidance behavior would prevent the promised revenues from being realized. At the same time, the promise of higher revenues would encourage Congress to continue its profligate spending. As a result, a tax increase would not lower the budget deficit.

Moreover, current tax rates can be maintained and even reduced and still allow for increasing national security appropriations and balancing the federal budget. Although a budget balance may not be achieved overnight, a firm commitment by the next president to spending control would bring about balance by the end of his or her first term.

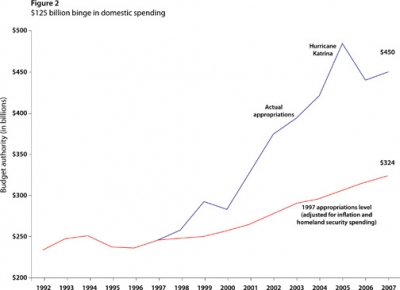

Balancing the federal budget without increasing taxes would require strong fiscal restraint. To achieve balance by the end of the next president ’s term, federal nondefense spending growth needs to be restrained to 2 percent per year instead of the currently projected 4.5 percent. This would be tough, but the federal government has been on a bipartisan spending binge for a decade. How large is this binge? Nondefense appropriations in 2007 were $125 billion higher than in 1997, adjusted for inflation and new homeland security spending. Cumulatively, this points to a nearly $900 billion excess for the decade. If the next two congresses were gradually to remove this excess and shave 1 percent per year from projected entitlement growth, the budget could be balanced.

But what about national security? Certainly, balancing the budget without raising taxes requires that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan be brought to a successful conclusion during the next five years. It does not require, however, that the U.S. troop presence in either country be eliminated. Nor does balancing the budget preclude overdue and necessary increases in the defense budget.

The costs of needed improvements in our national security, though seemingly large, are small when measured in the context of the federal budget. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), adding 100,000 active-duty soldiers and 60,000 reserve and National Guard personnel costs about $25 billion per year. Increasing the size of the Defense Department ’s procurement budget by 25 percent costs a similar amount. Each of these would add just 0.1 percent to annual federal spending —a small difference in the federal budget but a powerful addition to our nation’s security.

The current economic slowdown will increase the federal budget deficit this year and, in all likelihood, next year as well. But as the economy enters its recovery phase, rising taxes would choke off the recovery. The right policy, for both the economy and the budget, would be to make current tax rates permanent well before the scheduled increase. Giving investors greater certainty that current tax rates will be maintained will spur investment and aid the economic recovery, as it did in 2003. Federal budget balance will be achieved once the economy is again operating normally.

This near-term budget debate foreshadows the more significant long-term budget debate that the next president must lead. The CBO tells us that after a generation, Social Security and Medicare spending, left unchecked, will rise by 10 percentage points of GDP. Continuing the current hands-off entitlement policy would have severe consequences. The strategy of ratifying spending with higher taxes would require that all federal taxes rise by nearly 60 percent, bringing them to a European-level tax burden.

We still have time to prepare for the looming entitlement problem. Although the first baby boomers are beginning to retire, their real impact on the federal budget will not be felt for a decade. According to official budget forecasts, Social Security costs will claim 4.5 percent of GDP in 2013, no higher than their claim on GDP during the first half of the 1990s.

A near-term tax increase is the wrong way to prepare for the problem. Higher revenues will encourage Congress to raise spending, compounding the long-term budget problem. And the long-term tax increase required to fund unchecked long-term spending would probably reduce annual GDP growth by a full percentage point.

There are three ways to meet the entitlement challenge properly: change entitlements to slow their cost growth; eliminate all nonessential spending in the remainder of the budget; and, most important but often overlooked, adopt policies that promote economic growth. The greater the economic growth, the larger the economic pie, and the greater the public and private resources available to pay for entitlement obligations and other national priorities.

Last year’s federal budget illustrates the importance of economic growth to the budget’s overall health. The budget deficit was recorded as 1.2 percent of GDP, half its average level during the past four decades. This deficit was modest even though Congress has been on a decadelong spending binge; even though not a single entitlement program has been significantly reduced since the late 1990s and two entitlements, Medicare and farm support payments, have been significantly increased; and even though we are in the midst of costly but necessary wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The next president can fund our defense priorities, maintain tax cuts, and balance the budget. A tax increase consensus blurs the basic debates over our budget priorities in 2008 —and severely limits our choices in 2028.