- US

- Contemporary

- World

- History

During the first year after the fall of communism in Russia, there was intense interest in the whereabouts of the “party gold”—the assets of the ousted and outlawed Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Search efforts by President Yeltsin’s investigators and journalists found almost nothing, and today the issue is practically forgotten. At the same time, a different kind of search has brought to light a wealth not of gold but of documents—millions of records from the formerly secret party archives, the value of which continues to increase as new research is carried out at the Hoover Institution and elsewhere.

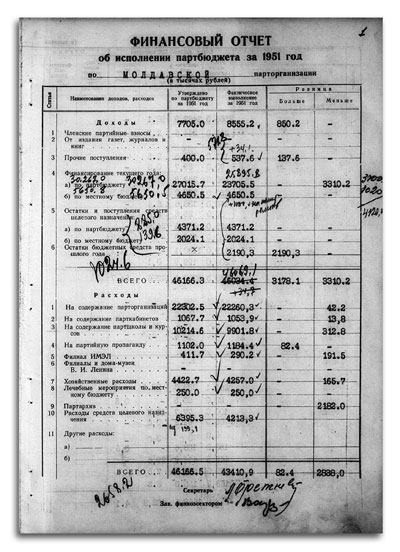

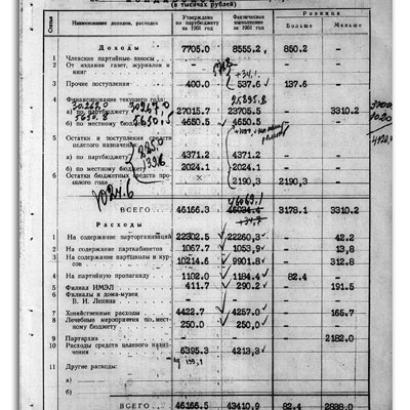

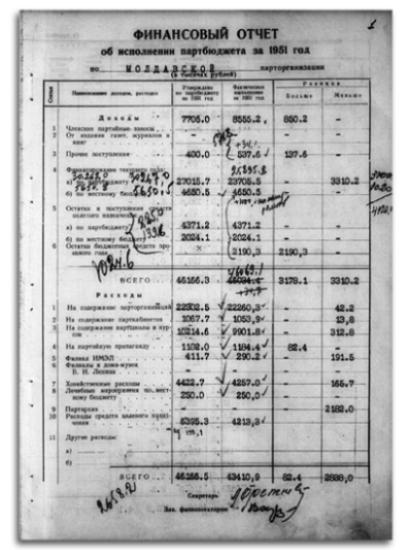

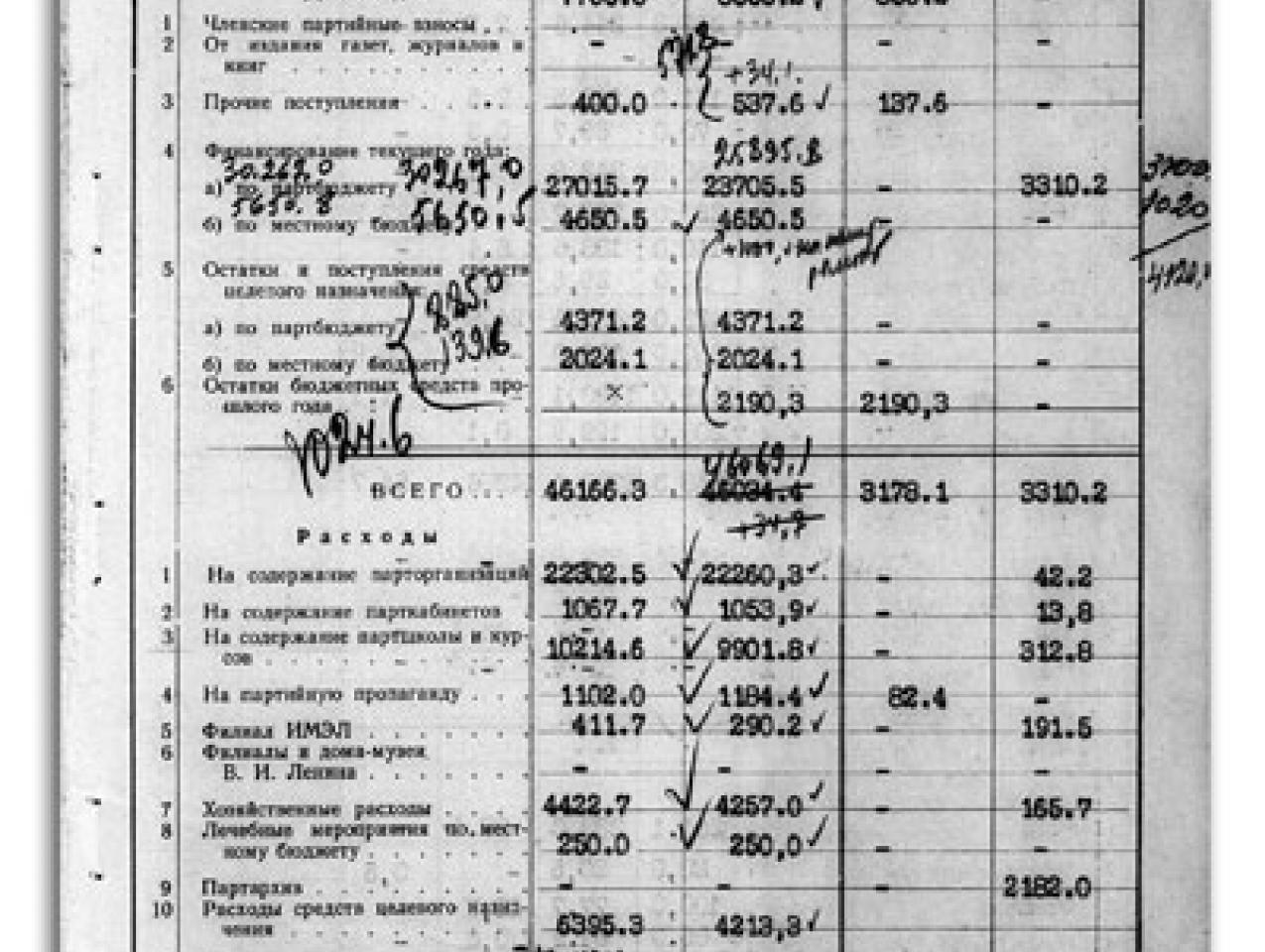

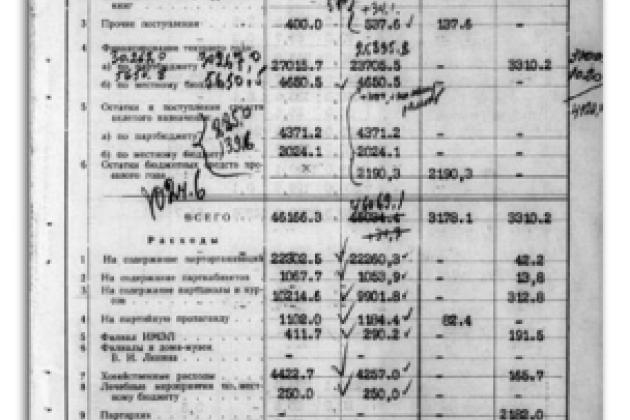

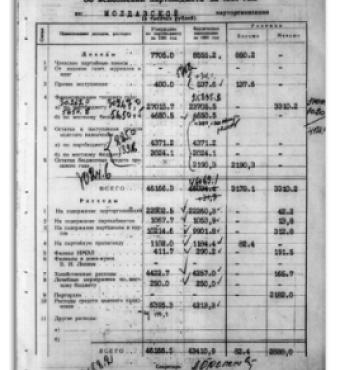

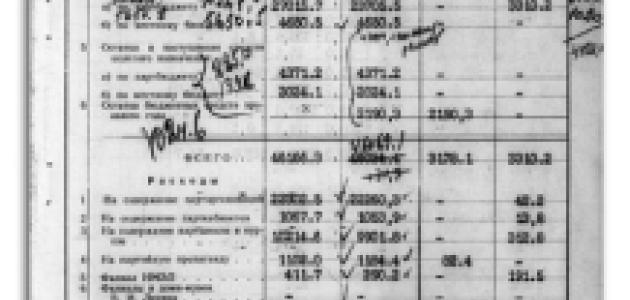

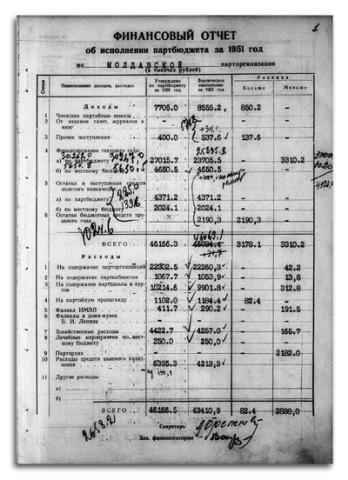

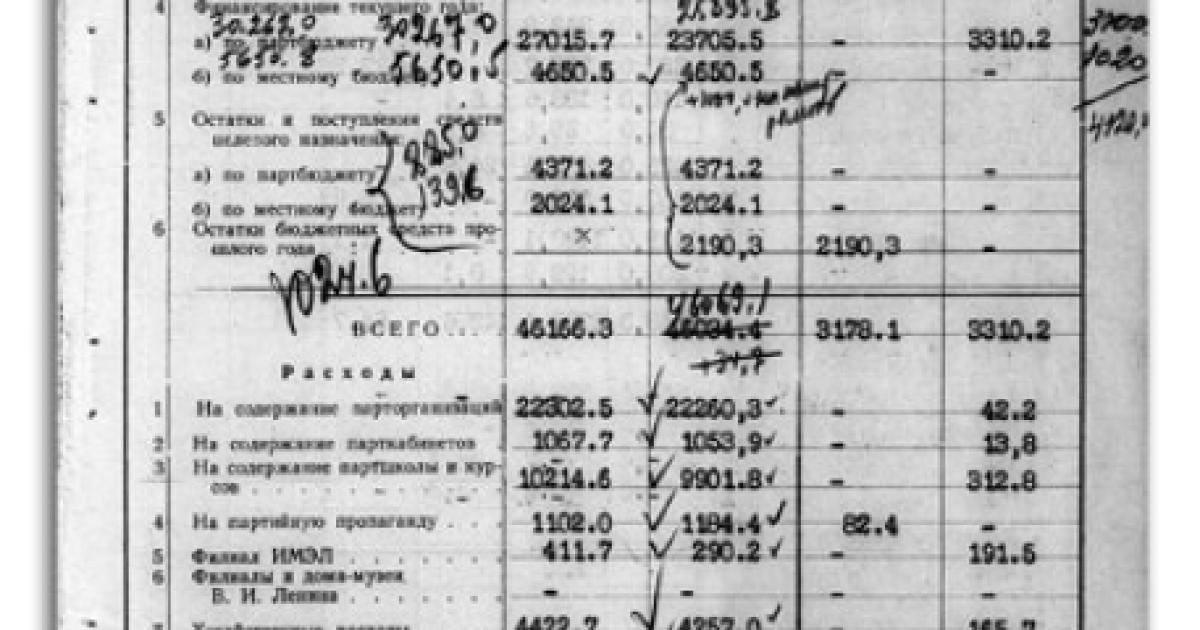

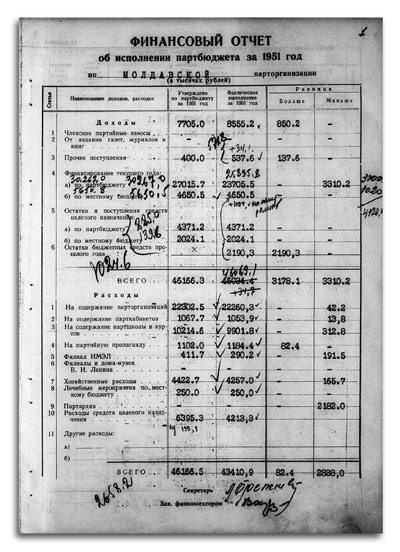

The CPSU financial records, as well as reports by party auditors and the party’s internal police, the Party Control Commission, portray the Soviet ruling party from a new perspective and shed new light on the complex and changing relationship between the party and the Soviet state. As far back as the Stalin era, for example, state subsidies to the party were limited and became more so, forcing the party to pay its own way. Lacking full state support, its finances thus became heavily dependent on membership dues—especially from the army—and on proceeds from party publishing operations. From the ledgers we learn the surprising fact that the Communist Party was run as a serious business, with attention to both revenues and expenditures.

MONEY MATTERED

The stereotype holds that the Soviet economy was largely moneyless, with economic plans seemingly focused on tons of steel and square meters of public housing rather than personal incomes or budget revenues. Prices were set by administrative fiat, causing pervasive shortages—meaning that it was the time spent in lines, not rubles earned, that determined who got what. In a world of triumphant materialism, why would anyone, especially a privileged party boss, care about money? Why was the ruling Soviet party on a budget at all? Why did it not simply take what it wanted?

Money apparently did have value in the Soviet reality. If it had been unimportant, party officials would hardly have risked their careers to get extra cash, as they clearly did. The files of the Party Control Commission testify to party officials’ appetites for extra income and the ingenuity with which they found ways to obtain it, both by misappropriating party funds and by extorting money from local governments and enterprises. Such extortion was often disguised as awards; for example, a local branch of the state bank would reward party officials for “facilitating the fulfillment of the financial plan” of the region.

Within the boundaries set by the official rules, party officers fought for transfers to large cities and tried to avoid assignments to low-ranking areas in the rural hinterlands. Prestige was not the only reason. The elaborate system of bureaucratic ranks was paralleled by a system of wage differentials. Any relocation within the system meant a change in the salaries, fringe benefits, and chances for further promotion.

Money was important even during the years of World War II, when rationing was pervasive and the Central Committee directly supplied regional party committees with many consumer goods. In fact, money mattered more to the wealthy party bosses, who could afford to buy produce in the markets or the nonrationed luxury goods in the state-owned retail stores. The meager workers’ wages were often exchanged for a ration card at the factory payroll window, whereas those with extra cash had some freedom of choice in spending. After the war, as the central control relaxed and the official stance against conspicuous consumption dwindled, both individual party officials and the party as an organization valued money even more, building private country homes, or dachas, and building up the party’s “emergency fund.”

SELLING IDEOLOGY FOR PROFIT

Repression and loyalty are the two pillars of dictatorial power. The security apparatus—the chain of successive dreaded acronyms, Cheka, OGPU, NKVD, and KGB—and the army served the first role. The party’s ultimate role was to supply loyal supporters for the regime by means of ideologically “guiding” the Soviet people (that is, ensuring compliance to the will of the dictatorial government) and by selecting loyal cadres for all branches of economy and public administration (the nomenklatura system of appointments). The repressive apparatus was fully funded by the state. By the same token, the party functioned as a subsidiary of the government.

Party budgetary data from the pre–World War II period show that party money indeed came from state sources and was spent largely on propaganda. Financial records from the postwar years, however, suggest that the state-party unity did not last. Soon after the end of the war, there is evidence of a divorce of party and state—or at least a firm separation—which is reflected in party finance. In April 1948, Dmitri Krupin, the Central Committee’s treasurer, summoned regional party officials to deliver the bad news: the easy life is over; the Central Committee will no longer foot the bills of regional party committees or supply them with materiel; and party committees will have to provide for themselves out of membership dues and proceeds from the party publishing houses.

In a theoretically moneyless society, we find that the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was run as a serious business, with attention to both revenues and spending.

What caused the new stance? One plausible explanation is the financial strain under which the Soviet government found itself in 1947–48 because of inflationary policies during World War II, a poor harvest in 1946–47, and the challenge of postwar reconstruction to be performed under the stress of the just-begun Cold War. The fiscal crisis manifested itself in the so-called monetary reform enacted in December 1947, which was tantamount to confiscating a large portion of the savings held by the population and accompanied a default on state obligations and the invention of new taxes. Meantime, there was also a trend toward a monetization of the economy, marked by the abolition of rationing in consumer markets (in 1947) and the state budget’s growing reliance on income and profit taxes (as opposed to the excise taxes favored in the 1930s). Finally, the state-party split might have been a sign of the new global ambitions of victorious Stalinism, which may have deemed party organizations inside the country to be of secondary importance.

The elaborate system of bureaucratic ranks was paralleled by a system of wage differentials. Any relocation meant a change in salary, fringe benefits, and chances for promotion.

One way or another, after this fateful step, the party began to emerge as an organization with its own interests, distinct from those of the central government. Until the late 1940s, party membership fluctuated; after that, it grew steadily. Given that the party organs could not control wages—even of their own employees—but were free to accept new members, the quest for revenue seems a likely cause of this steady growth in party membership. Membership doubled between the late 1940s and the late 1960s—from 6 million to 13 million—and eventually, by 1989, reached nearly 19 million.

Membership dues came from both civilian and military party organizations. The size of military contributions to the party budget is remarkable, reaching some 60 percent of the total membership dues in 1943, at the height of World War II. Even after the postwar demobilization, military dues never fell below 20 percent of total party revenue, twice as much as one would expect, given the representation of the military in the party membership. Similarly, Moscow and Leningrad, which had the largest party organizations, were the major dues contributors to the party budget; the rest of the country received subsidies from the Central Committee. The army and the two cities were similar in that they both were home to highincome professionals. Yet, whereas civil professionals could accept dues as insurance for a smooth-running career, the “party tax” on the army officers does not square with the customary view that the army under a dictatorship should be well treated, as befits a shield against internal and external enemies. In fact, party leaders never trusted the military leaders. Not surprising, the army denied its support to the party in the critical days of August 1991, when a rearguard attempt to reimpose central control collapsed.

Despite the growth in party membership, dues contributed a diminishing share of party revenue. Meanwhile, the profits from the party’s publishing business contributed a steadily increasing share. Between the 1940s and the 1960s, Pravda, the party’s major newspaper, increased its contribution from 2 percent of the party’s total revenue to 17 percent. Much of that revenue was in essence a tax on party members because subscribing to party periodicals was mandatory for them, but part of it was evidence of a sort of entrepreneurship. Like true business enterprises, party publishing houses enriched their catalogs with all sorts of literature, including fiction, as well as postcards, calendars, and the like. Whenever a spending increase was expected, the newspapers managed not only to increase the circulation but also to raise revenue by other means, including paid advertisements.

Soon after the end of World War II, there is evidence of a divorce of party and state—or at least a firm separation—which is reflected in party finance.

The publishing expansion was part of Comrade Krupin’s solution to the party-state split that he described in 1948. Seeking ways to raise money for the party committees, Krupin proposed collecting the profits from the regional party newspapers. Attendees at the meeting noted a problem with that idea: the regional publishing houses belonged to the Council of Ministers— the official government, headed by Stalin, not the party—and party committees could not control their finances. Krupin responded with a hostile takeover, apparatchik style. Because the accountants in the publishing houses were most likely party members, the party bosses were to establish “direct relationships” with them over the heads of their managers to ensure that the publishing houses turned over their revenues to the party, not the Council of Ministers. In this, Krupin’s plan resembles the takeover schemes that were widely practiced in the late 1980s with the approval of the party’s Central Committee. This part of the plan was successfully carried out. In the 1950s, government agencies published their bulletins in party-controlled publishing houses—not the other way around, as before—and the loyal accountants did their best to ensure that those clients paid full price.

The minutes of Krupin’s 1948 meeting confirm the power of the iconic Soviet bureaucrat. (Krupin’s only other recorded role in history is as the author of a denunciatory letter about the dissident poet Anna Akhmatova.) Yet it was this faceless apparatchik, not a Central Committee secretary, who coached the regional bosses about how to make the party pay for itself. No party leaders were present at the meeting or even mentioned in his speech; there was not even a ritual reference to the “wisdom of the great leader.” (At that time, an explicit or implicit blessing from the country leadership —a reference to an order or a random quotation from Stalin—was a must for any speaker in public or in a closed party meeting.)

Like true business enterprises, party publishing houses enriched their catalogs with all sorts of literature, including fiction, as well as postcards, calendars, and the like, and they worked hard to sell advertisements.

The state capped its subsidies of the party at 25 percent in 1948, and over time the party’s dependence on state subsidies diminished further. By the mid-1960s, after the party had moved to financial self-sufficiency, its pattern of spending had changed as well. Its function as a producer of ideology was less important; spending on domestic propaganda fell from 36 percent of the party’s total expenditures in 1938 to 20 percent in 1948 to 10 percent by the mid-1960s. In fact, the Central Committee had to continually remind regional party committees to spend the money allocated for propaganda on propaganda.

WHERE DID THE MONEY GO?

Like a cautious head of a household, the Central Committee put away some savings, accumulating what later became part of the sought-after “party gold.” The idea can be traced back to 1948: creating cash reserves to cover the initial deficits was the final part of the “Krupin plan.” In the mid-1960s, many party organizations ended their financial years in the black, generating more revenue than the Central Committee allowed them to spend. That surplus was routed to the off-budget “emergency fund” of the Central Committee, which outpaced the growth rate of official state budget revenues by a factor of four. That fund, as well as assets from official and unofficial sources, laid the foundations for the wealth of many “new Russian” families with party connections in their past, through paths that have yet to be brought to light.

Party budgets do not say how many millions of rubles the party bosses had accumulated by 1991 or where that money went. The CPSU financial statements do, however, provide numbers in several hundred thousand pages, thus requiring patient sifting and careful statistical analyses to mine the facts. These documents shed light on a side of the Communist Party that has never been fully understood and thus have the potential to add immensely to our knowledge of the Soviet regime and, by proxy, other one-party regimes.

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union, after spending its early decades merged with the state, eventually had more incentive to enhance its own well-being than to stabilize the regime. One symptom of this new disparity is how, using its control over appointments, it lured new members to the party merely for revenue purposes. This could explain the steady growth of the party ranks that began in 1950: by 1989, the party included 10 percent of the adult population of the Soviet Union (the same membership proportion as the Chinese Communist Party today). Young people joined the ranks in search of a better future—some for the nation, many for personal gain—only to discover that the party card entitled them to the right to pay for the salaries and benefits of an inept and exclusive party bureaucracy. Eventually, the party line of credit was exhausted.

Special to the Hoover Digest.