- Congress

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Health Care

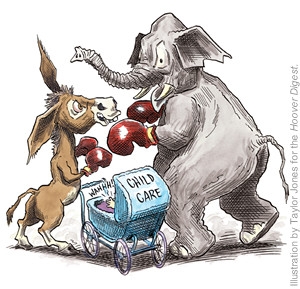

On March 30, 2004, 31 Republican senators joined 46 Democrats and one Independent in voting to increase federal child-care funding by an additional $6 billion over the next five years. The vote was seen as a direct rebuff to the White House and the Republican-controlled Congress who had called for a more modest $1 billion increase.

In some respects the vote was inconsequential. Its enactment depended on a welfare reauthorization bill passing the Senate and then going into committee with the House bill. But the welfare legislation died two days later without even being voted on, killed by one of the Senate’s many parliamentary procedures. It seems the Republicans and Democrats found plenty to disagree on and simply preferred to let welfare reauthorization expire for another year.

Among the points of contention, Republicans were arguing for stricter work requirements and an initiative to encourage healthy marriages. The Democrats generally opposed both these measures and instead were pushing for an increase in the minimum wage, protections for overtime pay, and an extension of unemployment insurance to workers whose eligibility is expiring—amendments outside the scope of welfare reform. Consequently, the most that can be expected are short-term extensions to the existing legislation like the seven that have passed since the fall of 2002.

The stalemate over reauthorization provides an opportunity to look more closely at that seemingly inconsequential Senate vote on child-care funding. Why has child care become such a major public policy concern? What is the connection between child care and welfare reform? And who are we to believe when it comes to deciding the appropriate cost for providing child care?

The Rise of Care

Before 1996, and as far back as 1935, when Congress created Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) as part of the Social Security Act, federal funding of child care was not a priority. As an entitlement program, AFDC provided cash to single-parent families with income and assets below a specified level. In its early years, the program focused on mother-only families where the primary reason for the father’s absence was death. Impoverished single mothers did not have to work in exchange for benefits.

This made perfect sense at the time, since only a small percentage of all mothers with children under the age of six worked—around 10 percent.

But over the ensuing 60 years, a lot changed. Skyrocketing divorce rates and out-of-wedlock births altered the type and number of single-parent families dramatically. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, the number of divorces per 100 marriages went from 16.4 in 1935 to 50 in 1995, an increase of more than 200 percent. Likewise, births to unwed parents were at one time very rare (less than 4 percent in 1940); by the mid 1990s they accounted for one out of every three live births. As a result of these and other factors, the number of single-parent families in the United States has increased nearly eightfold since 1950 (see table 1).

During the same period in which the traditional family in America was weakening, another radical change was taking place that would redefine the role of women in society—married women with children began working outside the home in earnest. As noted earlier, this was rarely the case in 1935 when AFDC was created.

Examining U.S. Department of Labor data for the period after World War II shows that the labor force participation of married mothers with children under the age of 6 had increased from 11 percent in 1948 to 64 percent in 1998. In the earlier years, married women with young children worked far fewer hours than single mothers; but in the 1990s the gap was erased, and today there is very little distinction in annual hours of employment and the percent working full-time, year-round. Women with school-age children (ages 6 to 17) have entered the labor force at even higher rates, and today outnumber stay-at-home moms three to one.

It’s not difficult to see how these two major societal shifts—single parents and working mothers—generated an enormous demand for child-care services. However, the federal government was late in recognizing the trend, in terms of both data collection and funding. Child-care statistics are scant prior to 1977, when the Current Population Survey reported that 4.4 million children of employed mothers received child care. By that time, single parents headed one out of every five American families and nearly half of all mothers were in the labor force. Still, child care expanded rapidly over the next 17 years, and by 1994, approximately 10.3 million preschoolers were in care arrangements. Significantly, all of the growth was absorbed by formal, organized child-care facilities. Caring for children was now big business.

The Federal Response

Major sociological shifts inevitably draw the attention of the federal government. As it relates to child care, the primary federal role has been in helping low-income families attain self-sufficiency and improve the well-being of their children. Thus the federal response to child care has been a push-and-pull effort.

The dramatic rise in single-parent families was a key factor in the growth of AFDC and subsequent dependency on welfare. Millions of families became eligible for cash assistance, pushing the AFDC rolls higher and higher each year. From just above 500,000 recipients in 1936, the program grew to serve as many as 14.2 million individuals in 1994 (see figure 1). The program, created in the Great Depression to support children who had lost their fathers, grew into a system of dependency composed largely of unwed mothers who were not working. The trend was unwarranted by national poverty rates and, because everyone who qualified was entitled to the assistance, unsustainable from a fiscal standpoint. The exploding welfare population was pushing the country toward a work-not-welfare mentality. It fell to the government to do something to stem the tide of welfare expansion.

The changing role of mothers in the workforce has an impact on national norms and welfare expectations, one that exhibited a pulling effect on the mothers receiving AFDC checks. Mothers of varying means had elected—for material, social, political, or any number of reasons—to start working outside the home, thus erasing much of the stigma previously associated with non-parental child care. Employment was seen as an appropriate, and possibly rewarding, role for the majority of mothers. This new paradigm, however, did not square with a dependent class of women caught in a system that punished them for taking a job. Additionally, the financial reality of living on welfare was a nightmare. The maximum monthly benefit in California in 1996 for a family of three was $565. Even with a couple of hundred dollars in Food Stamps, a public housing voucher, and other social resources, most families on welfare remained below the poverty level and without hope. The societal and financial incentives for mothers to leave welfare for work could no longer be denied.

The first tremors of change were felt in the late 1980s and early 1990s as the federal government and then the states began offering child-care subsidies to encourage work. Four new child-care programs were instituted with the aim of enabling and encouraging work, but a fragmented system of eligibility and varying coverage left much to be desired. Congress committed to a new vision of welfare when it enacted the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996. Its stated goal was to end welfare dependency by requiring and supporting the transition to employment. It did so in two significant ways. It ended the entitlement to welfare by replacing AFDC with Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and consolidated the four preexisting federal child-care programs into the Childcare and Development Fund (CCDF) block grant.

Most people are familiar by now with the work requirements and time limits put in place by TANF. Less attention has been paid to the support structures that were expanded to assist families transitioning into jobs. In addition to enhanced health coverage through Medicaid and strengthened child support enforcement measures, welfare reform substantially increased child-care funding. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, total child-care allocations in 1995 amounted to $3.1 billion. In 1997, the first operational year for welfare reform, child-care funding had grown 20 percent, to $3.7 billion. More significantly, the reform law gave states greater flexibility in redirecting some of their TANF funds to the CCDF and in paying for child-care services directly through TANF.

The plan laid out in 1996 to change welfare to workfare recognized and provided for the critical role child care would play in transitioning from government dependency to personal responsibility. But did it do enough?

The Cost of Care

The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry. — Robert Burns

Before the passage of welfare reform and every year since, voices of dissent have challenged its effectiveness and equity. When under consideration in 1996, opponents said the new reform law was an “outrage . . . that will hurt and impoverish millions of American children.” More recently, rumors spread that the economic recession would expose the weaknesses of reform and send thousands back on the dole. Until now welfare reform has proved all its critics wrong and more than vindicated its supporters.

Until now. The debate over child-care funding began with the same criticisms of the shortcomings of welfare reform, but this time the challenge stuck. Thirty-one Republican senators, including the majority leader, put their vote behind increased child-care funding, signaling a shift in conviction. The defenses of welfare reform were beginning to crack.

An influential bipartisan coalition insists that there is not enough child-care funding to fulfill the promises of welfare reform. Republican Senator Olympia J. Snowe vocalized their growing concern when she said, “If the aim of welfare reform is to move people off the welfare rolls and onto payrolls, if we want families to leave welfare and stay off welfare, we have to provide them with affordable child care.” The implication is that welfare reform has fallen short in its funding of child care and that the fiscal shortfall is harming the very families welfare reform was designed to save.

Let’s take a quick look at the numbers. First, the level of child-care funding has not gone down since the passage of welfare reform. In fact, funding is at a higher level now than at any other time in history. Looking at the period of time before and after the passage of welfare reform reveals a startling commitment of federal and state resources (see figure 2). The increased funding has enabled more than twice as many children to receive subsidized child-care services than were served in 1996. This was no accident. Welfare reform changed the rules in a powerful way by allowing states to transfer and directly pay for child-care expenses with TANF money. Reducing cash assistance payments by moving clients into jobs enabled states to spend more money per welfare recipient on support services such as child care. A dearth in funding just doesn’t exist.

Second, we can get a sense of whether there is an imbalance in funding for child care by examining the results of welfare reform. If many families were not securing work, were failing to keep jobs, or were re-enrolling in welfare, the system would not be supporting their transition to work. Fortunately, no such evidence of structural failure exists. In fact, the numbers keep getting better. Whether the scale is number of recipients, level of employment, or child poverty, the living conditions of families moving off welfare are significantly better than they were in 1996. Welfare rolls have been cut in half, to levels not seen since 1970. Employment rates of single mothers with children under age six (those with the greatest need for child care) are 13 percentage points higher. Nearly three million fewer children are in poverty because their mothers’ earnings continue to rise. We should and would be concerned about child-care funding if there were some evidence that welfare policy was contributing to a worsening of conditions for families. Clearly that is not the case. In fact, the flexibility of the system has allowed states to better prepare for and respond to increases in poverty during periods of economic recession.

Finally, there is a separate but related point to be made about the call for even more federal child-care funding: There will never be a limit. This time around the request was for an additional $5 billion over six years. Many of those who support increased funding, however, are desperately seeking a way to involve the federal government in the provision of child care on a universal scale. The reauthorization of welfare reform presents an opportunity for these advocates to further their agenda. Trumped-up waiting lists and emotional appeals concerning the poor quality of child care are indications of a far greater goal. And with this hidden agenda comes an even more hidden price tag. A review of several studies designed to reform the nation’s child-care system comes back with some sobering numbers: $60 billion a year for a unified federal child-care subsidy program, $54 billion a year for a child-care voucher program, $45 billion a year for a program that includes expanded parental leave, and (don’t laugh) $207 billion a year for a new comprehensive federal child-care subsidy system. Of course, you’re not likely to hear these numbers in the Senate chamber.

In the end it comes down to a question of cost. How much will it cost us to meet the need of care? One side invariably understands this question from a purely material perspective—what are the financial sums required to meet the need? The wealth of our nation is seen as a resource for solving our societal ills. It’s simply a matter of spending enough money to fix the problem. No matter how many times this formula fails to work and even exacerbates the problem, that side has no memory for failure.

Another side sees the financial requirements for care and attempts to balance these with the principles of limited government. It questions whether the federal government can and should take on every burden of society. Welfare reform is about lifting families out of poverty, but it is also about a return to the values of freedom, personal responsibility, and civic compassion. Child care has its price, but there are other costs that cannot be measured in dollars alone.