- Contemporary

- Military

- World

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Campaigns & Elections

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

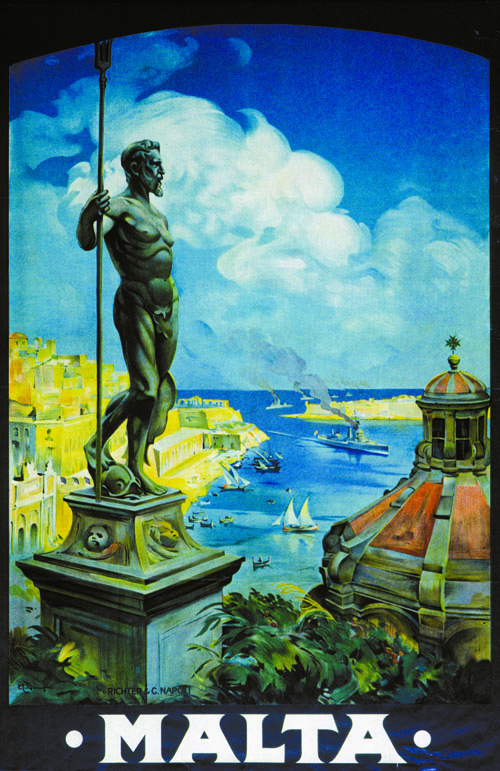

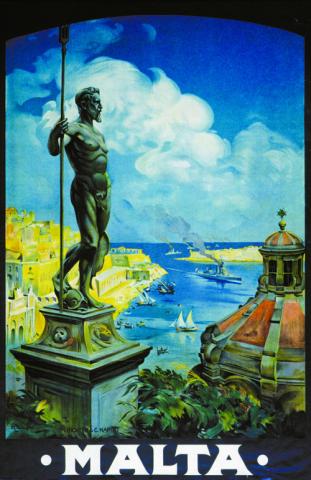

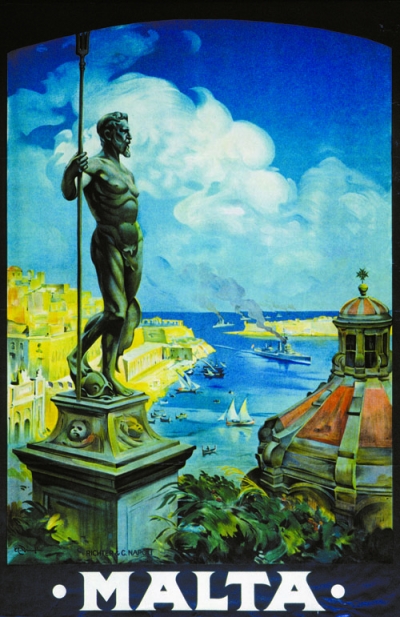

Neptune, god of the seas, watches over the Grand Harbor of Valletta in a Maltese travel poster from the Hoover Archives. He wields a trident—both a weapon to shake the waters in his wrath and a scepter to build islands and calm the waves.

The statue—a creation of Flemish-born artist Giambologna (1529–1608), who also executed a monumental Fountain of Neptune in Bologna—has watched many angry storms and placid tides come and go. Malta has been ruled by Muslims and Normans, Vandals and Visigoths. It knew Rome, Byzantium, and Napoleon. It has repulsed sultans and corsairs and been bombarded from the sky by Nazi Germany.

The knights of the Order of Saint John, whose predecessors guarded pilgrims in the Holy Land, came to the island in the sixteenth century. After forcing Ottoman besiegers back into the sea, they made Valletta their stronghold, naming it after their victorious grandmaster. They fortified the deep natural harbor and built hospitals, palaces, and churches, including Our Lady of Liesse (at right, with its eight-pointed Maltese Cross), which commemorates a medieval miracle. Many years later, the Neptune statue was moved from the fish market near Our Lady of Liesse to the Grandmaster’s Palace where, surrounded by ferns and hibiscuses in Neptune’s Courtyard, it can be visited today.

This poster of statue, church, and billowing clouds—and a line of arriving warships—represents an interlude of peace, foreshadowed by war. The image began as a painting by Edward Caruana Dingli (1876–1950), one of Malta’s most celebrated artists. It probably dates from the interwar 1920s. It then served as the cover of a collection of his watercolors published by the Maltese tourism commission. Years later, as the poster seen here, it was printed by the well-known Neapolitan bookbinders, engravers, and lithographers Richter & Company, whose posters and luggage labels enticed several generations of travelers to see the world.

But Caruana Dingli’s appealing, sun-splashed works express only a limited truth. “Caruana Dingli created a very specific and tailor-made view of Malta, one in which there is no suffering, displacement, or hardship, not even during one of the worst periods of the island’s history,” a modern Maltese artist, Madeleine Gera, wrote in Flair magazine. “Even as bombs fell on Grand Harbor, his paintings retained the serenity of the Mediterranean on a mild summer day.”

To Gera, Caruana Dingli “hints at a mythical idyll, in which fishermen left the harbor in their sturdy boats for a solemn day of fishing in the same waters where the [1565] Great Siege was fought, and nobody drowned.” Even the Neptune statue has a fig leaf.

But though an artist may refuse to acknowledge war, history obliges. One of Malta’s darkest chapters was World War II, when Italian and German bombers savaged the British-held island because of its strategic position. The Grandmaster’s Palace was damaged, though Neptune remained intact. Our Lady of Liesse also was damaged, but was rebuilt soon after the war.

In Caruana Dingli’s paintings, the Maltese rejoice in tradition and simple tasks. Perhaps there was some truth to his artistic Arcadia and its self-assured inhabitants. For their bravery during the war’s darkest hour, King George VI awarded the Maltese the George Cross—the first time the medal had ever been awarded collectively. Today the flag of independent Malta proudly displays this honor. The calm waters in this poster seem to suggest an abiding resilience, a tribute to the waves and to Malta’s past.

—Research by Yael Roberts