- History

Editor’s note: This essay is an excerpt of the new Hoover Press book, Learning from Experience.

Sometimes small events have a major impact on your thinking. I remember boot camp and the day my Marine Corps drill sergeant handed me my rifle. “This is your best friend,” he said. “Take good care of it and remember: never point this rifle at anybody unless you’re willing to pull the trigger.”

The lesson—no empty threats—was one I have never forgotten. Its relevance to the conduct of diplomacy is obvious, yet often ignored. If you say something is unacceptable but you are unwilling to impose consequences when it happens, your words will lose their meaning and you will lose credibility. But the lesson is also broader, as in any deal-making. If you are known as someone who delivers on promises, then you are trusted and can be dealt with. As my friend Bryce Harlow often said, “Trust is the coin of the realm.”

At the same time, we should never lose sight of the consequences of our threats or decisions. One memory of combat sticks with me. During World War II there was a sergeant named Palat in my outfit who was an absolutely wonderful human being. I had tremendous respect and admiration for him. During an action I ran over to where I thought Palat would be and yelled so that I could be heard above the din, “Where the hell is Palat?” After a brief pause came the answer: “Palat’s dead, sir.” The reality of war hit me hard. Wonderful people get injured and killed.

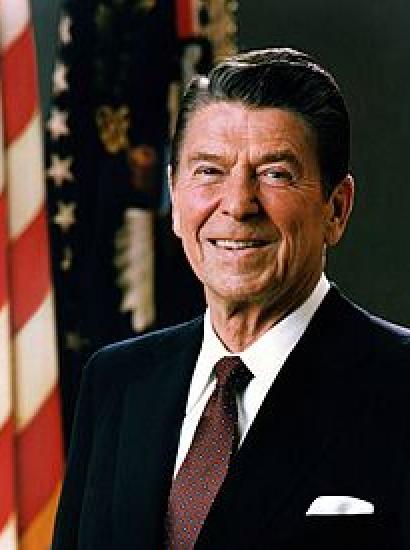

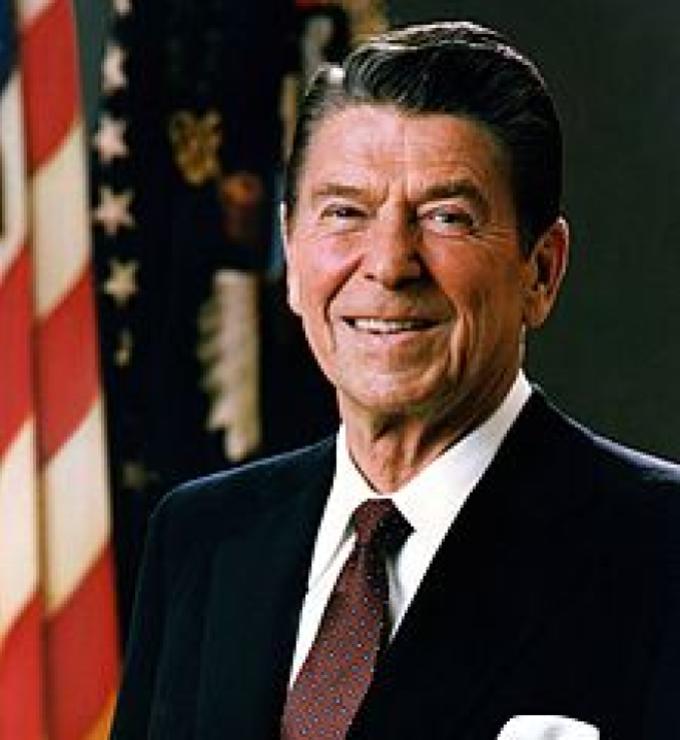

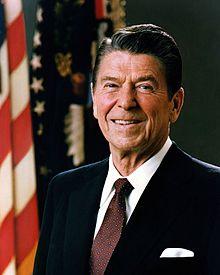

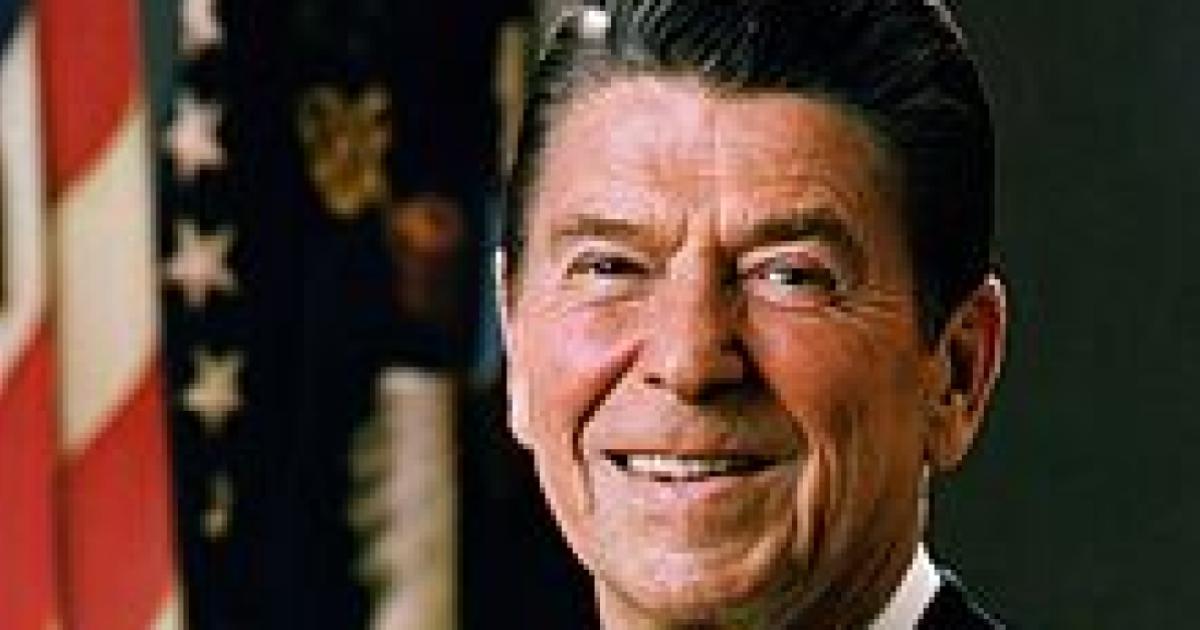

I often thought about Palat when I was in a position to advise President Reagan on the use of force. Be careful. Be sure the mission is a good one. Be sure your forces are equipped and staffed to win.

The worst day of my life was October 23, 1983, when, as Secretary of State, I was awakened to be told that 243 Marines had been killed in a suicide bomb attack on their barracks in Beirut. They were there on a peacekeeping mission. Surely they should have done a better job of laying out a perimeter defense in such a volatile area, but what, I asked myself over and over, should we have done differently? How could we have made their mission a better one?

In the Reagan era, we believed in peace through strength, but we used that strength very sparingly. We used force only three times during the eight years of Ronald Reagan’s presidency, and each time its use was sharp but limited. (Reagan, who always realized the importance of executing policy and not just announcing it, started to attract world notice when he fired the striking air-traffic controllers, who had broken their oath of office. He kept the planes flying. It was an early sign that, as many people said, “This guy plays for keeps.”)

The first use of force was in Grenada, where some three hundred Americans were virtually held hostage by a murderous Cuban-supported regime that had taken over from the previously democratically elected government. The island democracies in the Caribbean wanted American help in ousting Grenada’s regime but our requests to bring out the Americans by ship or plane were denied.

Our use of force was quick and decisive. The Americans were brought home; the first one to land knelt down and kissed the ground. We restored the previous democratically elected government, got Grenada back on its feet, and left. This was in fact the first use of force by the United States since the Vietnam War and it established that, if necessary, we would use our military capability.

The second use of force was retaliation against Libyan leader Muammar Gadhafi for ordering an attack on our soldiers in Berlin in 1986. We knew the building from which the attack orders originated. With a beautifully coordinated operation, the Navy and Air Force took out the building, and the operation was over.

Then, when Iran was interfering with Kuwaiti shipping in the Persian Gulf in 1987–88, we reflagged the tankers as American vessels and put them under the protection of the US Navy. While Iran’s president, Ali Khamenei, was making a speech to the United Nations saying the last thing Iran would do was to put mines in the Persian Gulf, we had Navy eyewitnesses taking pictures of Iranian forces doing just that. In one notable operation in September 1987, our sailors boarded an Iranian vessel, seized mines as evidence, removed the crew, and sank the ship. There was no loss of life, but we sent a clear message. We exposed the Iranians’ lie, let them know that we knew what they were doing, and showed them the consequences.

But strength and use of force are not the same. President Reagan’s buildup of our military power, the vibrant economy he brought about, and his contagious optimism are examples of strength without the use of force. Perhaps our most significant demonstration of strength came in 1983, after the failure of arms control negotiations with the Soviets. In that year, the NATO alliance countries, demonstrating great steadfastness amid an atmosphere of Soviet-generated threats of war, moved ahead in deploying intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) missiles.

Terrorism, and the new responses it would demand, was already on our radar in those days. In October 1984, I spoke about terrorism, labeling it a form of political violence and calling for a coherent strategy to deal with it. My speech was not welcomed by some but, fortunately for me, Ronald Reagan was in total agreement. We needed a realization in our country about the need to defend ourselves, I said. We had to have “broad public consensus on the moral and strategic necessity of action. . . . We cannot allow ourselves to become the Hamlet of nations, worrying endlessly over whether and how to respond.” Clearly, we needed to beef up our intelligence capabilities, I argued, provocatively at the time, and “our responses should go beyond passive defense to consider means of active prevention, pre-emption, and retaliation.” But I also warned:

[Terrorists] succeed when governments change their policies out of intimidation. But the terrorist can even be satisfied if a government responds to terror by clamping down on individual rights and freedoms. Governments that overreact, even in self-defense, may only undermine their own legitimacy, as they unwittingly serve the terrorists’ goals. The terrorist succeeds if a government responds to violence with repressive, polarizing behavior that alienates the government from the people. . . .

Terrorism is a contagious disease that will inevitably spread if it goes untreated. We need a strategy to cope with terrorism in all of its varied manifestations. We need to summon the necessary resources and determination to fight it and, with international cooperation, eventually stamp it out.

The speech caused considerable controversy, especially my call for preventive action. I considered that to be practically a no-brainer. But then I was closer, as Secretary of State, than were many others to acts of terror focused on our embassies and more aware, I thought, of the threat of terrorist acts closer to home. We did beef up our intelligence and a number of acts of terror were prevented because we intervened in time to stop them.

Sometimes the arts of strength are subtle and require not charging ahead but holding back. I recall a time in World War II after my Marine unit had taken a little island in the Pacific. We knew that natives on a nearby island made grass skirts, log canoes, and other souvenirs that we liked to send home. Occasionally, Marines were allowed to go to the island to trade, but for only two hours, so they wanted to make deals quickly. I noticed that the natives enjoyed bargaining. And why wouldn’t they? The negotiator who knows you are desperate for a deal will have the advantage. The one who wants a deal too much will almost always have his head handed to him. In this case, we insisted that the locals set a price and stick to it, and then the Marines could decide whether or not to buy.

I kept this realization in mind when President Reagan and I were negotiating with the Soviets. When I was asked at congressional hearings about the importance of making a deal, I would always say we were interested only in good deals. Add patience to your strength, and a good deal may come along.

All of these experiences were reinforced by my study of economics. I learned how to organize information to extract meaning, whether or not the information was about the economy. Economics also is about the importance of the lag between an action and its results. So it teaches a truly important lesson: think strategically. Don’t be dominated by the tactical issues of the day.