- History

- US

- World

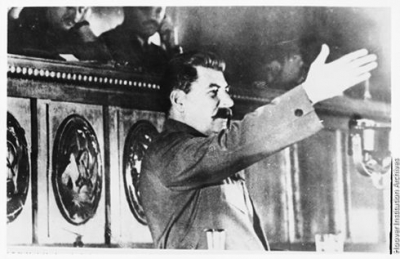

Fifty years ago, on March 5, 1953, Josef Vissarionovich Stalin died. One of the world’s great genocidists, comparable to Adolf Hitler not only as a mass killer but also as an anti-Semite, Stalin was preparing a large-scale pogrom, the outgrowth of what is today known as the “doctor’s plot.” How he died, when he died, and whether he was done in by his comrades, fearful of another purge, all remain a mystery to this day.

With all that was known about Lenin’s monstrous successor, there is another mystery that is even older than the anniversary of Stalin’s death: How could so many otherwise intelligent people, who were not Communist Party members so far as we know, have spoken admiringly of Stalin?

How could they have believed, as did U.S. ambassador Joseph Davies, a wealthy corporate lawyer, that the Moscow trials of Stalin’s fellow Bolsheviks in 1937–38 were genuine and not frame-ups? So persuaded was Mr. Davies that the Moscow trials, which he had personally attended, were genuine that he tried to persuade President Franklin D. Roosevelt to accept his opinions. His pro-Stalin reports to the White House can be found in the FDR presidential library in Hyde Park, New York.

George Bernard Shaw, the British playwright, told his audiences: “Even in the opinion of the bitterest enemies of the Soviet Union and of her government, the [purge] trials have clearly demonstrated the existence of active conspiracies against the regime. . . . I am convinced that this is the truth, and I am convinced that it will carry the ring of truth even in Western Europe, even for hostile readers.”

Think of what Davies, Shaw, and tens of thousands of Communist Party members, fellow travelers, and “useful idiots” were accepting as just verdicts. In 1938, the last year of the Moscow trials, almost all 80 members of the Council of War either died or disappeared. Marshals and generals, admirals and vice admirals were sentenced to death, as were thousands of other officers of all ranks. In that single year, there were more than 30,000 victims of the purge in the Red Army and the navy. In his 1956 “secret” speech after Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev said that “5,000 of Russia’s best officers were murdered during the blood-baths that followed the secret trial for treason of Marshal Tukhachevsky.” Assistant commissars of foreign affairs, as well as ambassadors, plenipotentiaries, and consul-generals, also perished. Virtually the entire staffs of Pravda and Izvestia disappeared, together with hundreds of authors, critics, theater directors and actors, members of the diplomatic corps, the secret police, even census takers.

Two famous leading British socialist intellectuals, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, wrote at the time: “Strong must have been the faith and resolute the will of the men who, in the interest of what seemed to them the public good, could take so momentous a decision.” The Webbs were referring to Stalin’s organized famine against the Ukraine peasantry in the winter of 1932 when between 5 million and 7 million died.

Then there was Walter Duranty, the New York Times’s Pulitzer Prize– winning Moscow correspondent, who, at the height of the famine in 1933, wrote: “There is no actual starvation or deaths from starvation but there is widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition. . . . Any report of a famine in Russia is today an exaggeration or malignant propaganda.”

World-class economist Paul Samuelson, a Nobel laureate, wrote in the tenth edition of his textbook Economics: “It is a vulgar mistake to think that most people in Eastern Europe are miserable.” This, mind you, in the aftermath of the 1953 East German uprising, the 1956 Hungarian uprising and the Poznan protests in Poland, the 1968 revolution in Czechoslovakia— all suppressed with bloodshed by Soviet tanks. In the eleventh edition, he took out the word “vulgar.” In the 1985 twelfth edition, that entire passage had disappeared. Instead, he and his coauthor, William Nordhaus, substituted a sentence asking whether Soviet political repression was “worth the economic gains.” This non-question was identified as “one of the most profound dilemmas of human society.” After 70 years of Leninism, Stalinism, and Maoism that took at least 100 million lives, this was still a dilemma?

It seemed to me utterly incredible that an otherwise great economist could parrot idiotic Marxist propaganda. At a time when the magnitude of the Soviet economic disaster was apparent even to the most willfully blind Marxists in Central Europe and the USSR, the 1985 Samuelson text offered this paragraph about the Soviet economy:

But it would be misleading to dwell on the shortcomings. Every economy has its contradictions and difficulties with incentives—witness the paradoxes raised by the separation of ownership and control in America. . . . What counts is results, and there can be no doubt that the Soviet planning system has been a powerful engine for economic growth.

But, as it turned out, there hadn’t been any economic growth for years.

Professor Seweryn Bialer of Columbia University wrote in 1983: “The Soviet Union is not now nor will it be during the next decade in the throes of systemic crisis, for it boasts enormous unused resources of political and social stability to endure the deepest difficulties.”

Even more incredible was the judgment of MIT professor Lester Thurow, who as late as 1989 wrote: “Can economic command significantly compress and accelerate the growth process? The remarkable performance of the Soviet Union suggests that it can. . . . Today [the Soviet Union] is a country whose economic achievements bear comparison with those of the United States.” Two years later there was no Soviet Union.

So here is the great mystery as we celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of Stalin’s death or murder: How could so many intelligent people have been so wrong, so damnably wrong, about communism, about Stalin, about the Russian Revolution, so oblivious of the human price being paid in the name of revolution? Nobody forced them to write such miserable lies. They couldn’t be jailed for such opinions. Why would such people (and there were thousands of them of otherwise high intellectual achievement) have willingly, even enthusiastically, written and published Soviet propaganda and offered it up as truth in books, academic journals, op-eds, monographs? Why do academics like Arch Getty and Robert W. Thurston even today still downplay Stalin’s guilt despite what the Soviet archives have revealed? All I can say is that nowhere has a statement of apology appeared from those who have lived to see their past writings about the Soviet Union exposed as infamous lies.

Without a cheering chorus of twentieth-century Western intellectuals, infected by a fusion of alienation, socialist utopianism, and anti-Americanism, communism might never have attained its ideological-military dominance in the free world that it did, especially during the Stalin era.