- International Affairs

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

KUWAIT CITY—

In the mid-1990s, the renowned political scientist Samuel Huntington provoked a worldwide debate with his thesis that foreign affairs would no longer be defined by war between nations but by the clash of civilizations. The experience of Kuwait, our small but indispensable ally in the Persian Gulf, suggests that we must stay attuned as well to the clash of civilizations within nations.

What grabs your attention as a newcomer and non-specialist are the cultural contradictions of Kuwait. You encounter them in the airport corridors, the luxury hotel lobbies, the rundown beachfront amusement parks, the corporate headquarters, and the truly extravagant shopping malls.

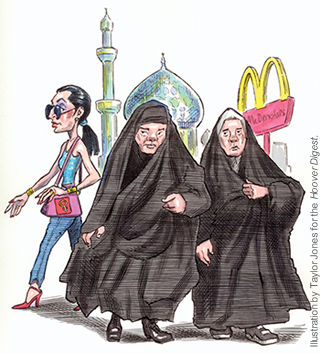

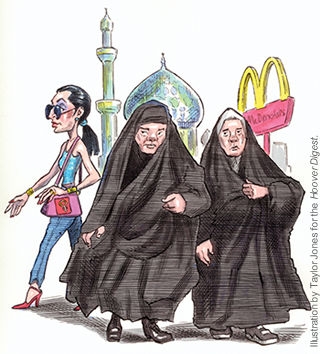

The culture of the Arabian desert and the culture of the West constantly come into contact in Kuwait and discover ways to peacefully coexist. Sultry young women sashaying in designer jeans and high, high heels pass by, without missing a beat, while women covered from head to foot in dark robes drift along the same streets like ghostly apparitions. Men in traditional garb—flowing white gowns, white headdresses, and leather sandals—confer with male colleagues who could pass for casual-Friday corporate lawyers. And perhaps most startling, since women in Kuwait lack the right to vote, men and women mingle freely on the street, at the mall, and in the workplace.

I traveled with a small delegation of journalists, think tankers, and Senate staffers as a guest of the Kuwaiti government to learn more about democratization in Kuwait, whose 850,000 citizens and 1.25 million guest workers live in a small, sun-baked land beneath which lies 10 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves. The special occasion was the July 5 parliamentary election, the tenth since the ratification of Kuwait’s constitution in 1962 and the fourth since 1991, the year that Kuwaitis typically, and with emotion, refer to as their “liberation.”

Kuwait is, in many ways, the most democratic of the Arab states in the region. This year’s campaign season was lively, with candidates for the National Assembly frequently renting space in vacant lots, pitching tents, giving speeches every evening, and providing a late buffet supper where their constituents’ conversation—that venerable and transcultural mix of politics spiced with grumbling and gossip—could continue.

Home to one of only two natural ports in the Persian Gulf, Kuwait has for hundreds of years been a commercial and cosmopolitan center. In contrast to Saudi Arabia, a large country with a closed and cleric-driven society, Kuwait is compact—from Kuwait City on the Persian Gulf it is an hour drive north to Iraq and an hour drive west or south to Saudi Arabia—and historically open to outside influences. Its constitution guarantees the equality of all citizens. Its ruling family, from whose ranks come a substantial number of the government’s ministers, tends to be Western-educated, enlightened, and generally progressive. Its 50-seat parliament is the most active in the Gulf; its press, the freest; and its women, who account for 34 percent of the labor force and two-thirds of the bachelors’ degrees in the country, the most economically active in the Arab world. Perhaps this is why the legal exclusion of women from voting and holding political office was on the mind of every politician, journalist, and activist with whom we met.

It’s not that the woman question was the only issue faced by voters. From the owner and editor in chief of Kuwait’s largest newspaper, to the chief executive officer of Kuwait Petroleum Company, to the former Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States, our interlocutors argued that the Kuwaiti economy is stagnating and that the remedy is privatization. This is a difficult proposition, however, in a country where 90 to 95 percent of the labor force is employed by the government, which generally pays more than the private sector. And designing institutions to create the right incentives will be difficult in a country whose oil wealth supports a massive welfare state with no taxes that generously funds its citizens’ health, education, and housing needs.

Yet it is suffrage that has become the focal point in the contest between Islamist and liberal forces. The liberal forces appear to have the fundamental law of the land on their side. The law prohibiting women from voting, we were told by former minister of oil and ex-Kuwaiti ambassador to the United States Sheikh Saud Nasser Al-Sabah, is “completely unconstitutional.”

In 1999, the emir of Kuwait dissolved parliament and, along with a variety of other liberalizing measures, sought to grant women the right to vote by decree. But even liberals opposed his action on the grounds that a law of that significance should arise from within the National Assembly. Shortly thereafter, when the liberals put the measure to the test, it came up two votes short. So far, court challenges to the prohibition on women voting have been dismissed on procedural technicalities, though one of the leaders of the Women’s Social and Cultural Society has a constitutional challenge pending and expects a judgment in the fall. An activist organization almost as old as the Kuwaiti constitution, the Society is composed of journalists, professors, businesswomen, medical doctors, research scientists, and lawyers. And its board, consisting of women ranging from the determinedly secular to the devoutly religious, has expressed confidence that, regardless of this court decision, women will be voting four years from now in the next National Assembly election.

On July 5 Kuwaiti citizens went to the polls. Liberals had been hopeful and Islamists worried, but the liberals fell from 9 seats to 3, and Islamists gained slightly, giving them about a third of the seats in parliament. Nevertheless, this is not the debacle for democracy that the Western press has made it out to be. Because most of the rest of the seats went to candidates loyal to the government (a generally liberal force in Kuwait), informed observers believe that this National Assembly, with the support—and perhaps at the initiative—of the government, will indeed enact legislation giving women the right to vote. If that happens, the further tempering of the clash of civilizations within Kuwait may well contribute to the tempering of the clash of civilizations beyond its borders.