- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

In Shiism there is a strange concept called mohallel. If a man divorces his wife in earnest—“thrice divorced” in the parlance of Shiite sharia—he can’t remarry her unless she has married and divorced another man. Rich men who divorce their wives in a fit of anger and then feel remorse and want them back often have to pay a reliable man a sum to be their mohallel—to “marry” the thrice-divorced wife with due discretion and then divorce her. There is a usually a retinue of reliable mohallels in each pious community.

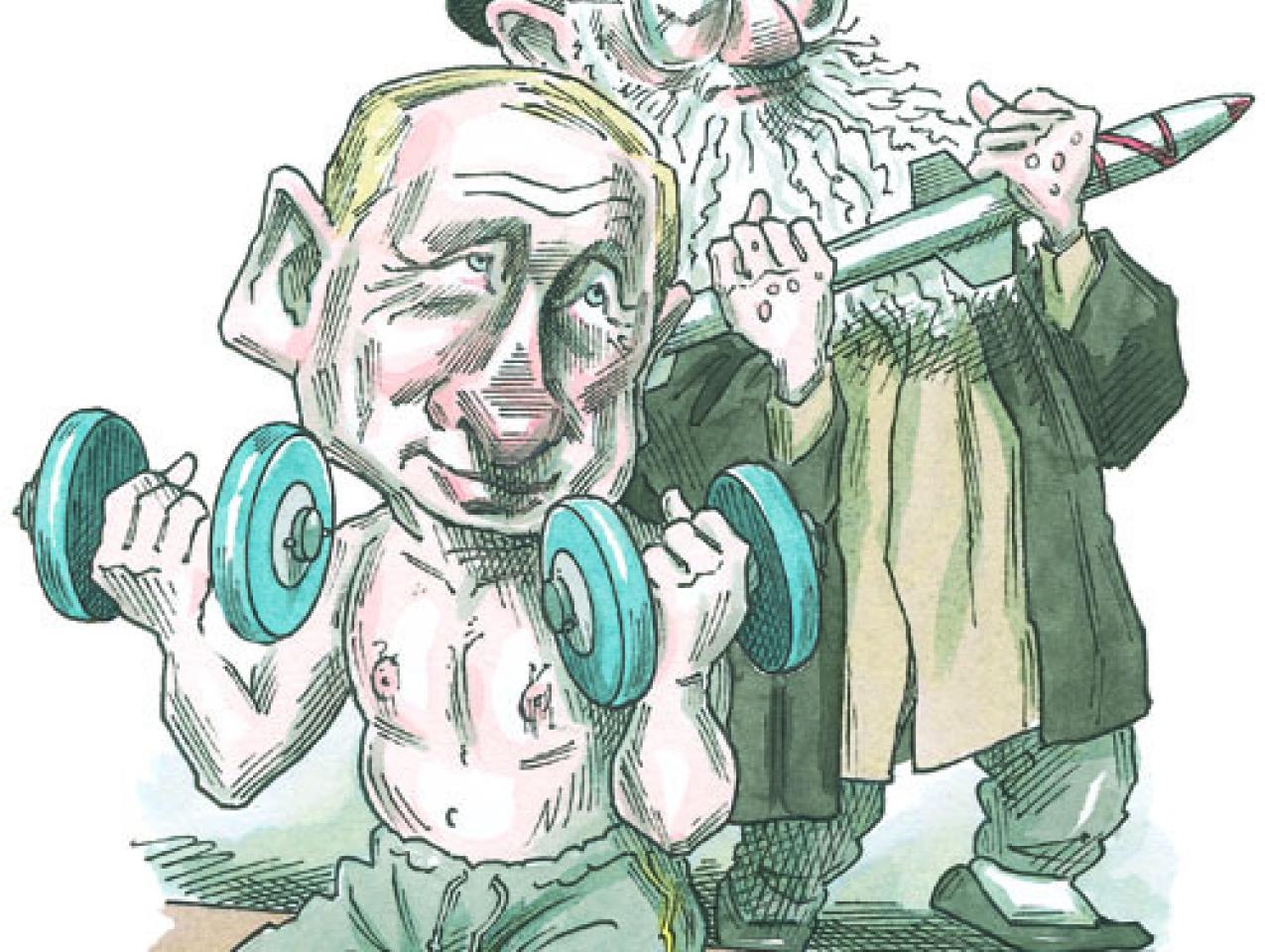

Russia and Iran are both ruled by men seeking absolute power—Vladimir Putin in Moscow and the Ayatollah Khamenei in Iran—and both are now shedding any vestige of a democratic appearance. Putin’s mohallel, Dmitry Medvedev, will be back in his old job of prime minister and his boss, Putin, will again take the reins of power. In Tehran, Khamenei is making his own power play, which is likely to help the clerics achieve their dubious nuclear aims.

In the past four years, if there has been an obvious area of difference between Putin and Medvedev, it has concerned Iran’s clerical regime. Medvedev has been more willing to work with the United States and the European Union on pressuring Iran to give up troubling aspects of its nuclear program. He even decided not to sell the clerical regime the S-300 missiles that would have substantially increased Iran’s ability to protect its nuclear sites from air attacks.

In Iran, more than six years ago, Khamenei handpicked Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to be his political mohallel—Ahmadinejad was meant to play the role of the pliant president and permit Khamenei to consolidate his power grab while hiding Khamenei’s insatiable appetite for more power. (The clerical quest for control over society is so notorious and brazen that it has even reached the realm of literature. A few years ago, Khamenei ordered the death of a writer named Saidi Sirjani who had dared to write a brilliant satire about a venerable man of devotion exchanging his pious soul for profane power.)

But as sometimes happens in the topsy-turvy world of professional mohallels, Ahmadinejad ended up having a passionate desire for power himself. He increasingly proved unwilling to play his expected role. He continued to challenge Khamenei. A few months ago the Iranian parliament—again, of course, handpicked by Khamenei—was even ready to impeach the impudent mohallel. But the instability that might come with such a move, and the possibility that impeachment procedures would empower the opposition, persauded Khamenei and his allies in the military to temporarily pull their punches.

Then a conservative member of parliament who is generally thought to speak for Khamenei revealed the remarkable fact that a group of lawmakers had been thinking about doing away with the office of presidency . . . for a while. With a leader like Khamenei, he said, why do we need a president? The lawmakers wanted to replace the job of presidency, elected by direct vote, with that of a prime minister, chosen by a pliant parliament that would appoint, and dismiss, whoever suited the ayatollah.

Direct election of the president by the people was one of the few concessions the clerics made when they seized power in 1979; it was a necessary bow to the democratic nature and aspirations of the revolution that brought them to power. But they, of course, placed a disproportionate share of power in the hands of the clerical leader—not elected by the people and not impeachable. Ever since, clerics have conducted an incessant effort to further curtail people’s rights. The first step was to require every candidate to pass “the beneficent supervision” (nezarate estesvabi) of a twelve-man body controlled by the leader. But the adage about absolute power and corruption again held true. Since the most recent fiasco with Ahmadinejad—when the mohallel proved unwilling to “divorce” power when Khamenei asked him to—the leader has apparently decided to throw caution to the wind and do away with the office of president altogether.

Moreover, this serious curtailment of democracy will be taking place just as the Muslim world is witnessing what could be its most important tectonic shift toward democracy.

The stories of these two mohallels—the pliant one in Russia and the reluctant one in Iran—are connected not just because they both make a mockery of democracy and the people’s right to vote. In Iran, Khamenei has been the most intransigent force in shaping Iran’s policy toward the United States and on the country’s nuclear program. In Russia, Putin has been more willing than Medvedev to challenge and embarrass the United States and align Russia with Iran and China in a new brotherhood of despotism. Putin’s latest display of power will only reinforce the power grab of Khamenei and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—and its affronts to democracy and diplomatic decorum in the Middle East and around the world.