Yasser Arafat’s death has generated widespread calls for Israel and the Palestinian Authority to resume negotiations aimed at a comprehensive settlement. Henry Kissinger, James Baker, and Brent Scowcroft are among those who think the time is ripe, now that the PA has elected a leader who opposes the intifada, for the United States to press the parties to return to the table. The British government is arranging a conference to push the process.

Others not only support comprehensive talks but call for abandonment of Israel’s plan to disengage from Gaza and four settlements in northern Samaria. Arieh O’Sullivan, defense correspondent for the Jerusalem Post, writes that “the moment Arafat was buried, the excuse that there is no Palestinian interlocutor fell away. Already the Labor Party is changing its position on Gaza because it is hoping a Palestinian leader might emerge who could make a lasting peace . . . if both Gaza and the West Bank were on the table.”

In fact, the Palestinians are far from ready to negotiate. The president, Mahmoud Abbas, opposes the use of violence but has made clear that he does not intend to use the PA’s forces against other Palestinians. Even if he changes his mind and tries to stop acts of terror, he may not succeed. Other Palestinians have yet to be elected to legislative and Council posts, and their positions on ending terrorism are not clear and likely to be even weaker than the new president’s. At best, unless Israel were to agree to proceed despite continuing violence, negotiations between the PA and Israel could begin around the time disengagement is scheduled to be completed (September 2005). To focus now on the resumption of comprehensive talks would therefore be premature, even if such talks in fact made sense at this stage.

Even if negotiations could be commenced sooner, their existence would deplete the parties’ capacities to implement disengagement and—most important—could undermine disengagement by introducing irresolvable issues and encouraging the parties to make unreliable commitments.

The important thing about disengagement is that, without any negotiated agreement, it would result in Israel evacuating 21 settlements and in Palestinian control of a sizable, contiguous piece of territory containing 1.4 million people, a port, an airport, and offshore natural resources. By contrast, none of the many previous plans to negotiate peace through bilateral agreements has resulted in evacuation of a single settlement or Palestinian control of an area sufficient for meaningful governance.

The Oslo Process promised movement but delivered only promises. Palestinians failed to end terrorism and persisted in spreading an ideology of hatred and death. Despite Israel’s partial withdrawals, the number of settlers and settlements increased, causing Israel to build roads and roadblocks to protect its citizens. The U.S. effort to reach a comprehensive agreement at Camp David failed, among other reasons, because the fundamental issues of refugees and Jerusalem could not be resolved. Those issues are if anything less likely to be resolved today. President Abbas, for example, still insists that Israel must accept the right of all Palestinians to return to Israel proper, a position that Israel will not accept.

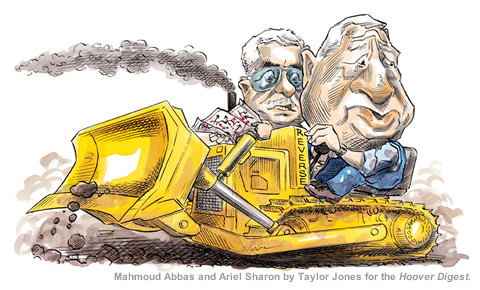

Disengagement is possible precisely because it is not based on any negotiated agreement. When Prime Minister Ariel Sharon concluded that Israel faced not simply sporadic acts of terrorism but a war fought with terrorist methods, he fashioned a strategy to win the war, rather than defending every Israeli position, however untenable. He agreed to build a barrier between Israelis and Palestinians and to “re-deploy” settlements to “reduce as much as possible the number of Israelis located in the heart of the Palestinian population.”

Realizing that Sharon’s plan would result in both a more secure Israel and enhanced prospects for creating a Palestinian state, President Bush agreed to recognize publicly that the barrier was necessary for Israel’s defense; that Israel had the right to protect itself from attacks; that the claimed “right of return” must be understood to mean return to the new Palestinian state; and that the few major settlements close to the 1967 border and containing most of Israel’s settlers would likely remain part of Israel after any final negotiation. These propositions do not preclude the Palestinians from securing different outcomes in direct negotiations, but the president’s acceptance of them gave Prime Minister Sharon’s plan the practical and political support he sought.

It is far from certain that disengagement will succeed. Although the United States and its negotiating partners support the plan, they have adopted a “show me” attitude and done little to help ensure its successful implementation. Sharon has thus far managed to move the disengagement policy forward but with great difficulty. In the latest of several political crises triggered by the disengagement plan, he has managed to form a new coalition between his Likud Party and a group from the Labor Party led by Shimon Peres. He now has a narrow but fragile majority, and he will need to hold it together despite serious differences on domestic issues as the process moves in stages to the actual removal of potentially violent settlers from Gaza.

Disengagement is vulnerable in Israel because it is indeed a response to terrorist acts and signals Israel’s willingness to abandon the expansive territorial aspirations of a small but powerful minority. A clear majority of Israelis understand, however, that disengagement is the rational, deliberate response of a strategist, aware that an indefensible position becomes no more defensible because of one’s determination to maintain it. Israel’s continued occupation of Gaza is untenable. The settlements there have about 8,000 Jews who control 20 percent of a territory containing 1.4 million Palestinians; and Israel needs 20,000 troops to defend these settlers, at an annual cost of $560 million. Israelis opposed to disengagement compare it to Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon. Yet, although that withdrawal was messy, it was long overdue. Today, the Lebanese-Israeli border is more secure than during Israel’s occupation, and no one would suggest that Israel reoccupy that area.

Instead of attempting prematurely to commence bilateral negotiations, the United States and other interested parties should help Israel and the Palestinians address the difficult issues on which a successful implementation of disengagement depends. They include

Security. Israel’s security would be threatened if Gaza is taken over by militants. The disengagement plan calls for Israeli control over the border between Egypt and Gaza and announces Israel’s intent to prevent importation of weapons. But Israel cannot end its responsibilities in Gaza without relinquishing control. Other solutions will have to be fashioned to secure the southern border and to regulate commerce.

Infrastructure. Israel is prepared to turn over the settlements and infrastructure but not homes. It is unclear to whom those assets would be given and what will be done with them. Militants, or thieves, could seize or destroy power lines, farms, and buildings. Ideally, Israel should turn over all the homes, but it is unwilling to see them occupied by terrorists. Mechanisms are needed to enable Israel to transfer and the Palestinians productively to use as many of the assets as possible; the homes could, for example, be sold by a mutually agreeable entity to responsible buyers and the income used for desperately needed public housing.

Economy. The economy of Gaza is in a disastrous state. The World Bank has proposed projects to help prevent the social catastrophe that could occur if Gaza’s economy does not improve, but it is unwilling to assume the risks of managing the projects it proposes. The United States and others interested in peace should be actively engaged in developing politically neutral entities, managed by professionals, to assume control of industrial zones, run facilities, and perform other functions needed to encourage investment.

Israel’s announcement on November 15 that it is prepared to coordinate disengagement with the Palestinians is a welcome development; a cease-fire would be a blessing; and Israel should also do all it can to facilitate Palestinian efforts to achieve stability. But outsiders should not attempt to force discussions to occur or become a vehicle for exchanging conditional commitments on the basis of potentially illusory undertakings that could disrupt disengagement itself.

Unilateral steps in the right direction are preferable to bilateral negotiations that lead nowhere. All efforts should now be directed to the many steps needed to ensure that disengagement succeeds.