- International Affairs

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

When the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1973 authorizing military action in Libya, the first casualty took place neither in beleaguered Benghazi nor in Ghadafi's Tripoli but in the very heart of the trans-Atlantic alliance. The German decision to abstain from the vote and, in effect, to side with Russia and China, alongside Brazil and India, represented a break with the foreign policy tradition that had prevailed for decades—since the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949.

As an episode in contemporary political history, the German abstention on Libya is rich in implications. It sheds light on fault lines in the western alliance. It teaches a lesson about the importance of American leadership (and the consequences of its absence). And it offers important insights into aspects of Germany’s political culture, which will remain influential long after the Libyan war.

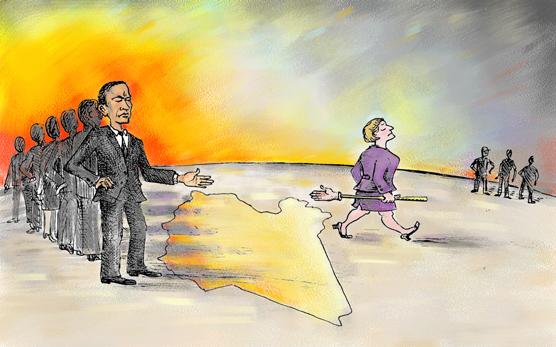

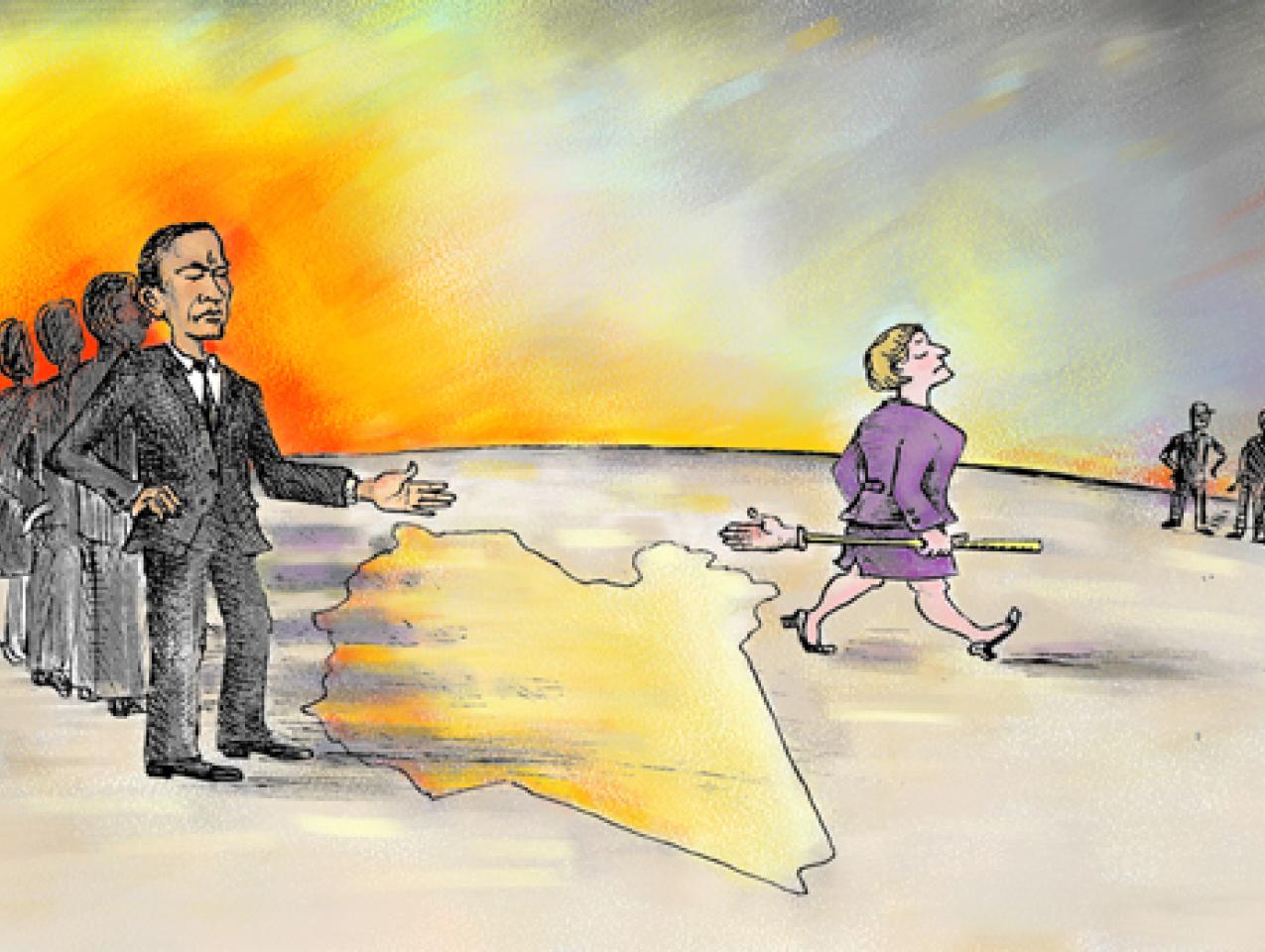

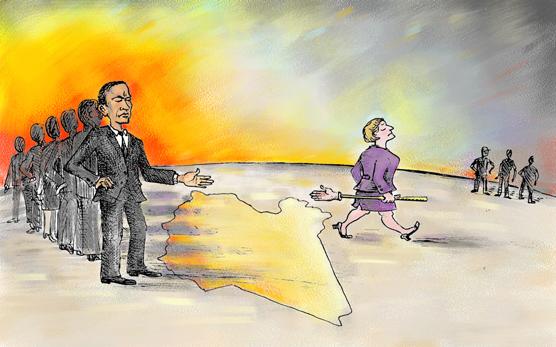

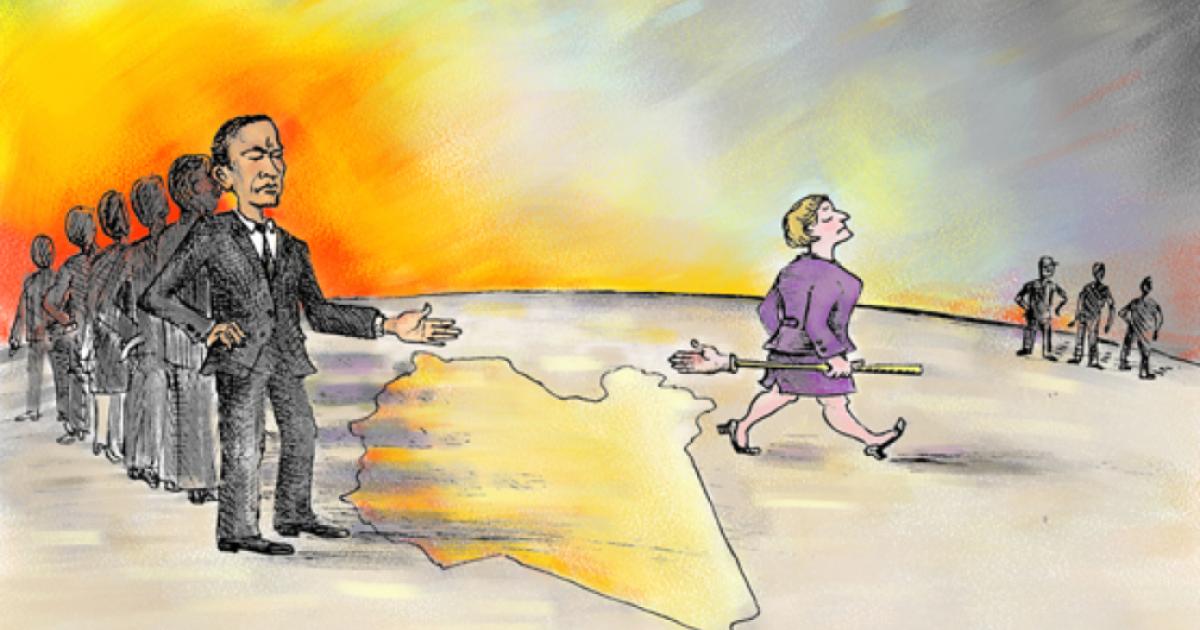

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

The abstention provoked vociferous criticism in Germany, from conservatives dedicated to Westpolitik and from leftists committed to human rights. Yet public opinion polls have been mixed on the vote, and there is certainly no evidence of any appetite for direct German engagement in Libya. The abstention was therefore a significant political statement, a refusal to side with the U.S. And that is worth scrutinizing.

Germany has disagreed with the U.S. previously, most notably in its opposition to the Iraq War. Yet when then-German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder criticized the Iraq policy of the Bush administration, he did so at the side of French President Jacques Chirac, the leaders of what Donald Rumsfeld famously dubbed "old Europe." In contrast, in the Libyan vote, Germany not only broke with the U.S.; it also broke with the major European powers, France and the United Kingdom. Viewed from the perspective of post-World War II German policies, this was an extraordinary step. The vote left Germany isolated in the West, and in some very curious international company.

The German abstention raises concerns regarding the coherence of the western alliance. Can the U.S. count on Germany? How committed is Germany to the protection of human rights and the spread of democracy? Twenty years ago, watching the explosion of public opposition to the Gulf War, German cultural critic Karl Heinz Bohrer declared that in a moment of crisis, Germany would likely not be a reliable partner for the West. His prediction seems to have been accurate. Commenting on the German abstention in the Libya vote, the British commentator on European politics, Timothy Garton Ash, accused the Germans of a Dolchstoss, a "stab in the back," a historically loaded term, signifying treachery and betrayal from the era of the Weimar Republic.

Can the U.S. count on Germany? How committed is Germany to the protection of human rights and the spread of democracy?

Yet post-war Germany, a successful liberal democracy, has aspired to nothing more than reliability and stability in the western order. How could this best of the "good European" countries turn its back on France and England, let alone the U.S., and choose to side instead with the likes of Russia and China?

Part of the answer reflects the specific character of the international scene at the moment of the Libyan crisis. While the Franco-German alliance has been the centerpiece of Western European politics for decades, the Germans harbored some legitimate doubts regarding the motives behind Nicolas Sarkozy's impassioned advocacy for military action in Libya. As much as the French president has appealed to public sympathy for the rebels and their opposition to Ghadafi's dictatorship, he has also been striving to profile himself as a bold international leader, as he heads into a crucial electoral season. Germans can reasonably be reluctant to be dragged into the Libyan affair in order to protect Sarkozy's reelection prospects.

But the more important aspect of the international context that contributed to the stunning German willingness to break with the traditions of Westpolitik and to abstain on Libya was no doubt the mixed messages from Washington. President Barack Obama did, eventually, come around to the notion of protecting the Libyan rebels, but he was extraordinarily slow in arriving at that decision, and along the way, he signaled disinterest and lack of commitment. Moreover, after the adoption of the UN resolution, he underscored how quickly the U.S. would try to disengage: this is not a fight he wants to stick with.

In short, the U.S.’s stance on Libya was not compelling. While Washington wanted to avoid being accused of countenancing the massacre that Ghadafi had promised for Benghazi, it also wanted to keep its involvement as limited as possible. For Germany, the signal from Washington could only mean that Libya was not a genuine American priority: then why should it be one for Germany? The German abstention and the rupture it has left in the western alliance are a direct result of the Obama administration's choice to avoid leadership. Washington gave Berlin plenty of room to duck and cover.

For Germany, the mixed-signals from Washington could only mean that Libya was not a genuine American priority: then why should it be one for Germany?

The German abstention was equally, if not more, a decision driven by domestic predispositions and concerns, rather than international politics. In light of Germany’s role in the two world wars of the twentieth century, there is a well-known pacifist tilt in German political culture. When all is said and done, German pacifism is preferable to German militarism. In the Libyan vote, however, the issue was not whether Germany would participate in military action to protect the rebels but simply whether Germany would vote to authorize such a campaign. There is a point at which pacifism flips into apathy and disregard, a desire to avoid conflicts altogether. Germany can reach this point very quickly.

This pacifism is an enduring element in post-World War II German politics, and it was especially important in this case, since the UN vote took place immediately before important regional elections. On some level, all politics are local, but in this case Germany made a significant foreign policy decision on narrow domestic grounds. The German coalition government, led by Conservative Chancellor Angela Merkel and Free Democratic (Liberal) Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle, presumably calculated that supporting the Libyan resolution would hurt them at the ballot box. They suffered significant defeats anyhow.

The point however is not the election results themselves, but that basing such an important foreign policy decision on regional elections epitomizes what cultural critic Bohrer has labeled a German "provincialism." This political inwardness always gives priority to local matters, no matter how urgent the international question is—for example, the imminent slaughter in Benghazi.

There were however some significant, if subtle, international implications of the abstention: that Germany chose to side with Russia, rather than with the West, is a remarkable turn of events given the hardly distant history of German unification. Why should Germany suddenly feel so cozy in the shadow of the Kremlin? Part of the answer is Germany’s profound dependence on Russian natural gas, especially since Vladimir Putin has proven himself quite willing to play the energy card very strategically in recent years.

The abstention was a significant political statement—a refusal to side with the U.S., leaving a rupture in the western alliance.

Other formerly Communist states in central and eastern Europe, especially Poland, have been anxious about the evidence of emerging lines of collaboration between Berlin and Moscow. A Germany sliding toward a more neutralist position between the Atlantic alliance and Russia elicits memories of the "finlandization" problem of the Cold War era.

Russia is also a significant market for the export-driven German economy, and so are China, Brazil and India, who made up the abstentionist block. In other words, the German abstention not only represented a break with its tradition of cooperating with the foreign policies of the western liberal democracies; it also signified a vote for a new cooperation with key partners in the globalized economy. The political values of some (though not all) of the BRIC nations may be unsavory to many Germans, but the economic opportunities are as indisputable as they are evidently irresistible. There are therefore very plausible reasons for Germany not to have felt too uncomfortable in such company during the Libya vote.

Finally, instead of treating the abstention as indicative of German politics in general, we should also view it as the particular responsibility of Foreign Minister Westerwelle (whose political star as leader of the liberal Free Democrats has suddenly fallen as a result of the major losses in the regional elections). The liberalism of Westerwelle's party has always combined disparate strands: individual civil liberties, free-market (and low tax) economics, and a German national orientation toward the global economy. The latter has sometimes included an explicitly pro-Arab inclination. It is not surprising then that a German Free Democrat politician would resist endorsing military action against an Arab country, even at the cost of breaking with the West.

What is surprising however is that if one surveys German foreign policy since unification, one finds that it was the left-leaning Socialist-Green coalition under Gerhard Schröder that joined with the U.S. in the Kosovo War in 1999, but it was the right-leaning Conservative-Liberal coalition under Angela Merkel that chose to abstain in Libya. The cases of Kosovo and Libya are by no means identical, but the contrast highlights how ambiguous Germany's role in the western alliance is likely to remain in the future.