- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- California

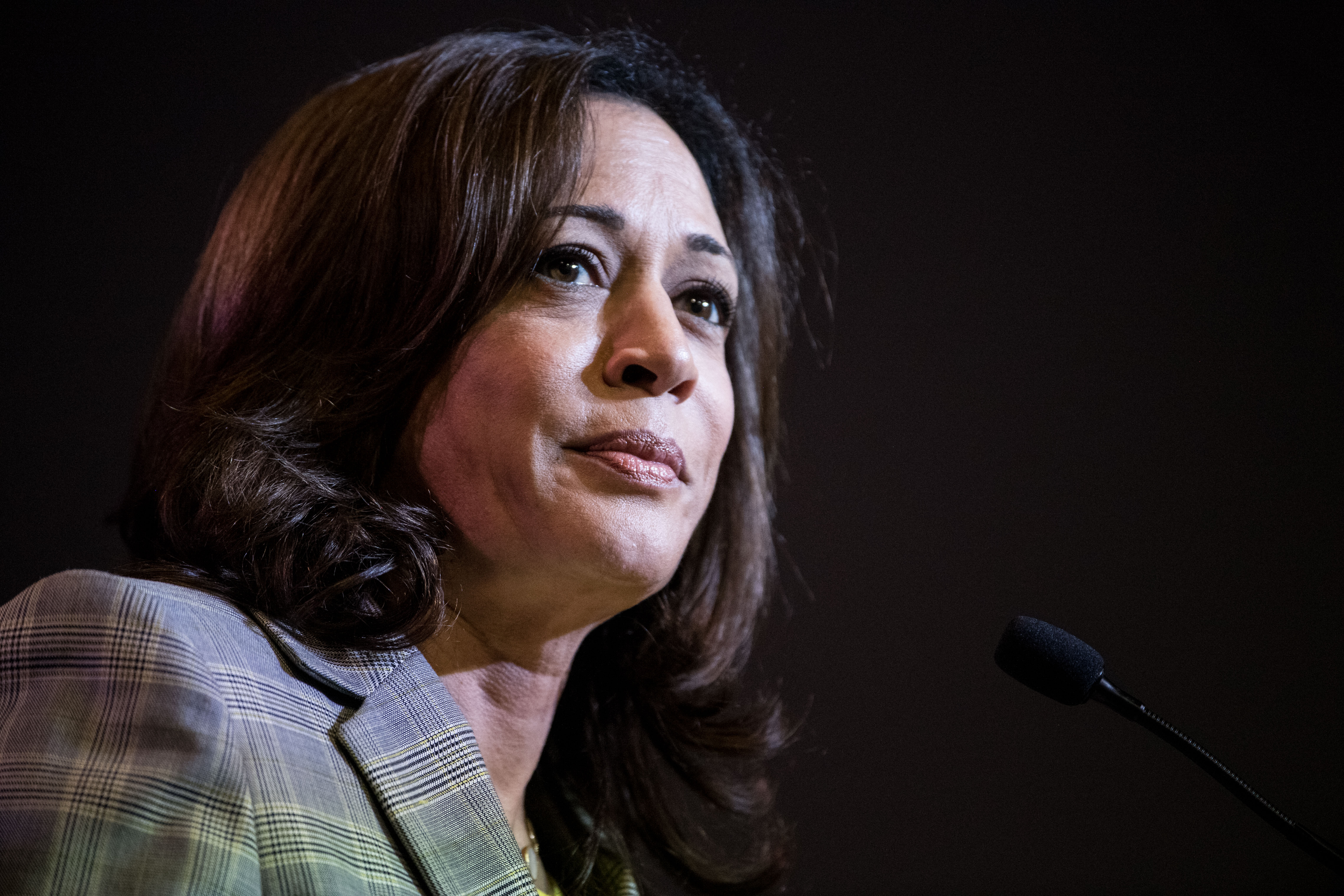

Her name is not on California’s March primary ballot, but the aftermath of that vote could affect Vice President Kamala Harris in a roundabout fashion.

We’ll get to that in a moment, but first a few thoughts on the political health of the first woman—and first person of color—to hold the second-highest elected office in the land, not to mention the first Californian to serve in that capacity since Richard Nixon did so seventy years ago.

Harris’s last public appearance in the Golden State was a late January rally in San Jose to underscore the Biden administration’s commitment to reproductive rights—not exactly a “Daniel in the lion’s den” moment. And a few days before that: stopping by Sacramento to address a California Legislative Democratic Caucus reception (“From environmental justice to workers’ rights to marriage equality,” she later tweeted, “California has led the nation in the fight for progress for generations”).

“Progress” seems to be the operative word with Harris, as in: three years into her current job, has she made tangible progress as an acceptable alternative to President Biden should he change his mind about seeking reelection?

The answer, or so the polls indicate: not really.

A year ago, this Berkeley IGS poll sampled California voters on the notion of Harris running at the top of the Democratic presidential ticket as Biden’s replacement. Only 37% of respondents expressed some level of enthusiasm, with 59% feeling the opposite. Meanwhile, 538’s polling average gives the vice president an approval rating of 36.4%, with 52.8% disapproval (in the spring of 2021, Harris’s numbers were the opposite: 48% approval; 37% disapproval).

YouGov’s polling average is more promising for Harris: in mid-February, a 45.6% approval rating. But that’s a five-point drop in support from when she first assumed the vice presidency, while her disapproval rating’s climbed almost eight points, to over 53%.

Still, there’s a ray of polling sunshine for America’s vice president: per a recent Emerson College survey, Harris fares better than California governor Gavin Newsom or Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer in a hypothetical matchup with Donald Trump (Harris trails by three points, with Newsom and Whitmer trailing by double digits).

By now, political scribes and pundits have devoted a considerable amount of print space and bandwidth to the question of what ails Harris’s vice presidency—those sympathetic to her cause offering a “dealt a losing hand” defense.

And they have a point.

Early into the Biden presidency, Harris was tasked with (and gladly accepted) leading the charge on a federal voting rights bill that never stood a chance in a divided U.S. Senate. Dubbed the administration’s “border czar” in charge of finding a remedy for the migration crisis at America’s southern border, Harris was in fact setting herself up for failure given that the Biden White House spent the better part of three years offering an Animal House-like “all is well” defense of the chaotic situation down south (this Axios piece chronicles considerable dysfunction within the Biden Administration regarding border security, with the vice president wanting to play a limited in the internal policy debate).

Then again, Harris can be her own worst enemy. For example, there’s this disastrous exchange with NBC’s Lester Holt from back in June 2021 (after which, the New York Times reported, the vice president “all but went into a bunker for about a year, avoiding many interviews out of what aides said was a fear of making mistakes”).

Holt: “The question that has come up, and you heard it here and you’ll hear it again, I’m sure, is, Why not visit the border? Why not see what Americans are seeing in this crisis?”

Harris: “We have to deal with what’s happening at the border, there’s no question about that. That’s not a debatable point. But we have to understand that there’s a reason people are arriving at our border and ask what is that reason and then identify the problem so we can fix it.”

And later in the same interview . . .

Holt: “You haven’t been to the border.”

Harris: “And I haven’t been to Europe. I don’t understand the point you’re making. I’m not discounting the importance of the border.”

Of course, there’s an easy remedy for the Biden White House should it decide Harris is too much of a political liability moving forward: drop her from the ticket (here’s a column suggesting just that).

But would it ever happen? A “dump Nixon” movement fizzled out at 1956’s Republican National Convention—the failed putsch occurring despite then president Eisenhower’s publicly discouraging the idea (“I will promise you this much, that if anyone ever has the effrontery to come in and urge me to dump somebody that I respect as I do Vice President Nixon, there will be more commotion around my offices than you have noticed yet”).

Sixteen years later, with Nixon himself seeking a second presidential term, his vice president was on the receiving end of “dump” speculation—Nixon reportedly wanting to part ways with Spiro Agnew but opting not to do so for fear of alienating conservative voters (Agnew having delighted the right by characterizing America’s liberal intelligentsia as “nattering nabobs of negativity” and “an effete corps of impudent snobs”).

Moving ahead twenty years, to 1992, then president George H. W. Bush also reportedly entertained the idea of a new running mate—or so claims this book—only if someone else were willing to break the bad news to Dan Quayle (“He hadn't objected in principle to the idea of doing Quayle in,” an unidentified source said of Bush. “He didn't want his fingerprints on the weapon. . . . He could not bring himself to be more than a passive actor in the drama, hoping against hope that Quayle would jump without having to be pushed”).

As circumstance would have it, the second President Bush also toyed with a ticket-change. In his personal memoir Decision Points, George W. Bush wrote that he considered replacing Dick Cheney with Tennessee senator Bill Frist, to “demonstrate I was in charge.”

Obviously, there’s a pattern here: presidents (and their political minions) flirting with the idea of dumping the vice president, only to back away for reasons having to do with loyalty or fear of political reprisal. And that latter fear—reprisal—might be a legitimate concern were there to be a concerted move on Kamala Harris: a party immersed in identity politics risking a backlash with Black and female voters.

So what next for Kamala Harris? Look for more news articles like this one reporting that her participation in campaign messaging and fundraising strategizing translates to “a more assertive role for a running mate than has been traditionally been the case.” But Harris’s detractors won’t be silent—billionaire Bill Ackman, for example, has been pushing a narrative of Harris as California state attorney general refusing to investigate Herbalife for pyramid-scheme behavior, perhaps to help her husband, whose law firm did business with the company.

Meanwhile, Harris would be wise to take a more active role in California politics. Which takes us back to the March primary (here’s some recent polling data on the electorate’s state of mind).

Once President Biden sweeps to victory in the Golden State, the California Democratic Party will turn to the business of selecting delegates to August’s national convention in Chicago. The Golden State delegation will consist of 496 delegates, 424 of them pledged to a candidate on the first ballot (here’s how the delegate selection process works).

Why this matters to Harris: imagine an alternate political universe in which Biden is no longer running and convention delegates are free to vote as they please beginning with the second ballot. If the vice president’s political brain-trust is on top of its game, the goal should be to line up as many Harris-friendly California delegates as possible in advance of any convention plot twists—as opposed to a slate of Biden delegates who’d switch to, say, Newsom as a “favorite son.” Indeed, shoring up California should be a priority for either Harris or Newsom, as the Golden State’s total of 494 delegates (about 22% of the delegates needed for the nomination) is nearly the equivalent of the 501 delegates in three other states (Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) ruled by Democratic governors who could offer themselves as presidential alternatives.

One last thought with regard to Harris (and it’s timely, after news reports that governor Ron DeSantis reportedly was on fellow Floridian Donald Trump’s short list of potential running mates, only to promptly remove himself from such speculation): the odds of an all-California Newsom-Harris ticket materializing as the result of this reimagined national convention.

Setting aside the question of whether Harris would bow to Newsom and acquiesce to another four more years as a White House junior partner, there’s the pesky matter of the 12th Amendment of the US Constitution. It stipulates: “The Electors shall meet in their respective states and vote by ballot for President and Vice-President, one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves.”

While that doesn’t rule out two candidates coming from the same state, it does prevent electors from choosing both. Now, imagine a scenario in which the all-California ticket prevails but with fewer than 324 electoral votes (a sum surpassed only twice in this century’s six presidential elections). Absent California’s 54 electoral votes and thus preventing a 270-vote majority, either the House of Representatives would choose the president-elect (each state’s delegation counting as one vote) or the Senate would decide the vice president–elect. (As this would be handled by a new Congress next January, it adds more intrigue to what’s already shaping up to be a unique political year should Democrats regain the House while Republicans flip the Senate.)

Dump Kamala Harris? History suggests we dump the thought of it.

But as for “open convention” speculation: maybe it’s in the vice president’s best interest to engage in a little convention planning, well before she packs her bags for Chicago.