- World

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- History

What would Ronald Reagan say? Democracy movements rising to power in Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan; elections in Afghanistan and Iraq; a new Palestinian leader who appears genuinely committed to establishing a democratic state; pro-democracy demonstrations in Beirut. What would the man Margaret Thatcher called the Great Liberator make of it all?

Pondering this the other day, I decided that if William Safire could commune from time to time with his old boss, Richard Nixon, in the New York Times, then I ought to be able to commune with my old boss in this publication.

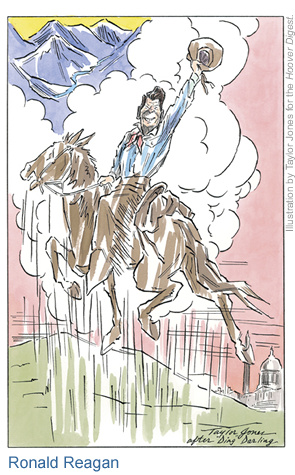

Picturing the Gipper’s famous grin, I shut my eyes. A moment later, I detected the scent of live oak and the tang of horse sweat. I heard a whinny, then the squeak of leather as a big, square-shouldered man dismounted. “Remember the inscription I used to write on those photographs that showed me up at the ranch, riding my Arabian stallion?” Ronald Reagan asked. “‘This isn’t the South Lawn, it’s heaven?’ Well, by golly, I was right about that. Whoa, boy. Settle down. You’d like to ask a few questions?”

PR: If I may, Mr. President. You called on Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall, but these days all sorts of walls seem to be falling. Are there any particular lessons we ought to learn from what has been taking place?

RR: [With a self-deprecating shake of the head] Well, I’m no historian. But while the professors are writing their big books, maybe I can offer a couple of simple observations. The first ought to make everybody happy. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were right—Adams sits a mount pretty well for a stocky little fella, by the way—but they were right. We really are endowed by our Creator with certain inalienable rights, and no matter what his culture, his religion, or his language, everybody would rather have a say in electing a government than have some tyrant tell him how to live.

Remember that 1982 speech to Parliament that I delivered over in London?

PR: I have it right here on my desk. I was looking it over before I got in touch with you.

RR: There’s a passage in the middle of that speech that I inserted in my own handwriting—you speechwriters did a good job most of the time, but every so often I did a little writing myself. It’s about the 1982 election in El Salvador. Would you read that passage aloud?

PR: My pleasure, sir. “On election day the people of El Salvador braved ambush and gunfire, trudging miles to vote for freedom. A grandmother who had been told by the guerrillas she would be killed when she returned from the polls told the guerrillas, ‘You can kill me, kill

my family, and kill my neighbors, but you can’t kill us all.’ The real freedom fighters of El Salvador turned out to be the people of that country.”

RR: Now, does that 1982 election in El Salvador remind you of anything?

PR: The 2005 election in Iraq.

RR: See what I mean? People are people. They’ll take freedom whenever they can get it.

PR: Your second observation, sir?

RR: A lot of folks won’t like this one. Powerful as the aspiration for freedom can be, sometimes it isn’t enough by itself. Sometimes the United States needs to step in.

Look at Eastern Europe: East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968—Soviet tanks rolled in every time. Then came Poland in 1981.

In March, the month I got shot, the Soviets began moving forces in and around Poland, and it looked for all the world as if they were going to do to Walesa in Gdansk what they’d done to that Dubcek fella in Prague. What stopped them? American resolve. One of the first things I did when I got well enough to sit up in my hospital bed was to write Brezhnev a letter with the bark off.

Our 600-ship navy, the invasion of Grenada, support for freedom fighters in Afghanistan and Latin America, the Strategic Defense Initiative—the revolution of 1989 was soft as velvet because the United States had spent eight years being hard as steel. Young George Bush understands all that. He knows there’s nothing quite as important to the cause of human liberty as the armed forces of the United States.

PR: People often compare President Bush with you. What do you make of that comparison, sir?

RR: Well, I certainly like his style. He makes a few important decisions every day but delegates the rest to his staff, exercises, gets plenty of rest, and leaves Washington for his ranch just as often as he can. Wonderful wife, too. A lot like Nancy. Elegant and feminine, but strong. On substance, though, the chief executive George W. Bush reminds me of most is Harry Truman.

PR: President Truman, sir? Not yourself?

RR: Well, before becoming president I’d spent half my adult life reading and writing and giving speeches about the Soviets. All I had to do once I took office was act on what I’d already decided. But Harry Truman? When he took office he had no idea what he was getting into—heck, for a while he thought Stalin was a good ally. But in just a few years Truman recognized what Stalin was really up to, rallied the country for the struggle against Soviet aggression, and developed the basic strategy of containment that would remain in place until I came along four decades later.

George W. Bush? When he took office young George was expecting an easy time of it, not the first attack on our territory since Pearl Harbor. Yet here we are, just four years later, and George W. Bush has rallied the country for the struggle against terrorists, won a war in Afghanistan, won a war in Iraq, and developed a strategy for promoting democracy that has already transformed the Middle East and fostered democratic advances as far away as Kyrgyzstan.

PR: Then you’re optimistic about President Bush’s democracy agenda, sir?

RR: Well, we shouldn’t expect too much from the new democracies. Just look at all the trouble France, Germany, and a few of the other old democracies have been causing. But have you got a copy of the speech I delivered at Moscow State University in 1988?

PR: Yes, sir. I have that speech right here, too. “Freedom is the recognition that no single person, no single authority of government has a monopoly on the truth, but that every individual life is infinitely precious, that every one of us put on this world has been put here for a reason and has something to offer.”

RR: A speech about freedom, to the children of the Soviet apparat, right there in the very capital of an evil empire that had enslaved tens of millions. And if that could happen—well, you bet I’m optimistic.

The former president glanced over his shoulder toward the West. “Now, if you’ll excuse me,” he said, “the sun is getting low. Come on, boy. Time to get you back to the stable.”

Ronald Reagan mounted up and began to ride away. Suddenly he reined in his horse, shifted his weight in the saddle, and turned back to me. “I still love riding into the sunset,” he said. Then he grinned, gave me a wink, and rode on.