- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Economics

Hamlet condemned “the law’s delay.” He might have had second thoughts had he lived today in the Village of Port Chester, northeast of New York City. There the sharp-elbowed world of real estate development shows why moving too fast can be just as dangerous as moving too slowly.

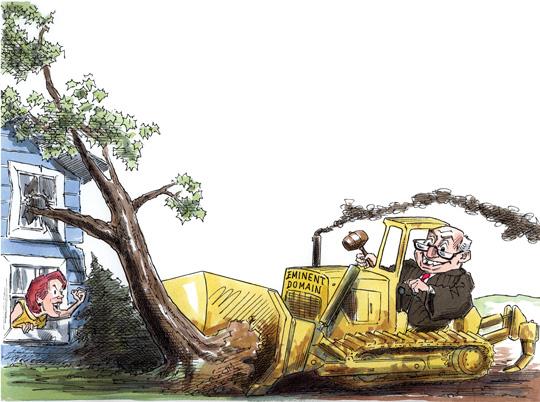

In 1999, Port Chester established a redevelopment area in which new projects could be built only after getting approval from a village-designated private individual, Gregory Wasser, to whom the municipality inexplicably delegated its regulatory authority. In 2003, two owners of a plot within the redevelopment zone, Bart Didden and Domenick Bologna, asked Wasser for permission to build a CVS pharmacy. According to Didden and Bologna, Wasser responded, “Either pay me $800,000 to build or give me a piece of the action, or I’ll have the village take the property.” The day after Didden and Bologna spurned the offer, Port Chester did indeed start the takings process. Wasser then arranged for Walgreen to develop the site.

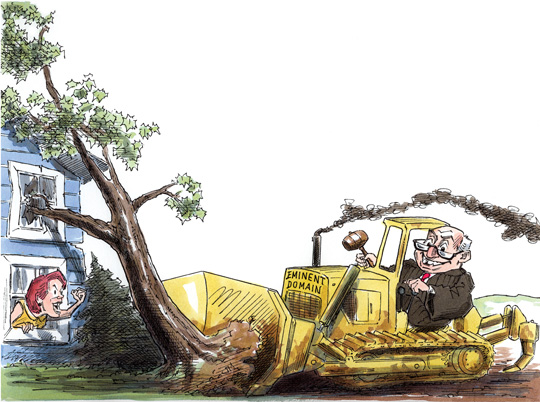

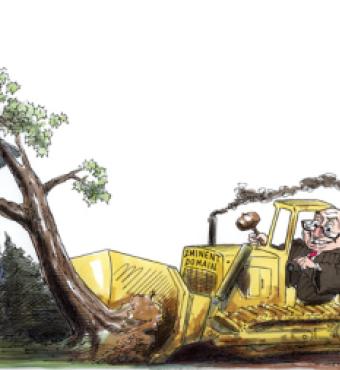

This little episode represents a sorry example of what political actors can legally do with unchecked condemnation power. Why, one might ask, wasn ’t Wasser’s land grab an unconstitutional taking for private purposes? (Didden sees it as extortion; Wasser defends his actions as promoting urban renewal.) This constitutional question of when takings are “for public use” has been front and center since the Supreme Court’s 2005 decision in Kelo v. City of New London, which allowed the city to take private homes for private development.

Didden and Bologna lost a federal case to block the taking. The Supreme Court, duly burned by the public backlash against its decision in Kelo, refused to hear the case. Of course, Didden and Bologna are entitled under the U.S. Constitution to just compensation for the property taken and are litigating in state court over the amount. How much will they get? Here lies another open wound in the modern takings system.

In theory, just compensation should make the property owner as well off as he was before his property was taken. But that never happens in practice. Didden and Bologna won ’t get any compensation for the work they did to put together the CVS deal. Nor will they recover their legal, expert, or appraisal fees. The village, for its part, has paid undisclosed legal fees to fight Didden. It has also, so far, paid Didden and Bologna $975,000 for their parcel. Didden terms that a “down payment” on the final sum, which could equal or exceed the property’s assessed valuation of $1.6 million.

It takes no financial wizardry to see that the expenses on both sides of this high-priced battle are a social waste if all they do is replace a CVS pharmacy with a Walgreens. The Port Chester saga reveals the institutional flaw of modern takings law. Undue judicial deference creates large amounts of government discretion, which in turn invites self-interested actors to game the system. Current constitutional law subjects most development rights to government vetoes, which invite perpetual intrigue and personal favoritism.

Yet our Supreme Court remains on a constitutional holiday. Over and over the justices blithely assume that conscientious planners acting in good faith are entitled to ample discretion in allocating the costs and benefits of our social life. Sounds great on paper, but the sorry saga of Port Chester shows that when it comes to real estate, we have a government not of laws but of politicians. In matters that they really care about, such as race and free speech, judges are quite capable of seeing through airy abstractions to harsh realities. Why can ’t they do the same for property rights?

This plea will not sound out of place to those who recall that our Constitution historically rested on the proposition that private property was the guardian of every other right. Having lost that vision, we can count on more Port Chesters in our future —more official abuses of the state’s eminent-domain power.