- Health Care

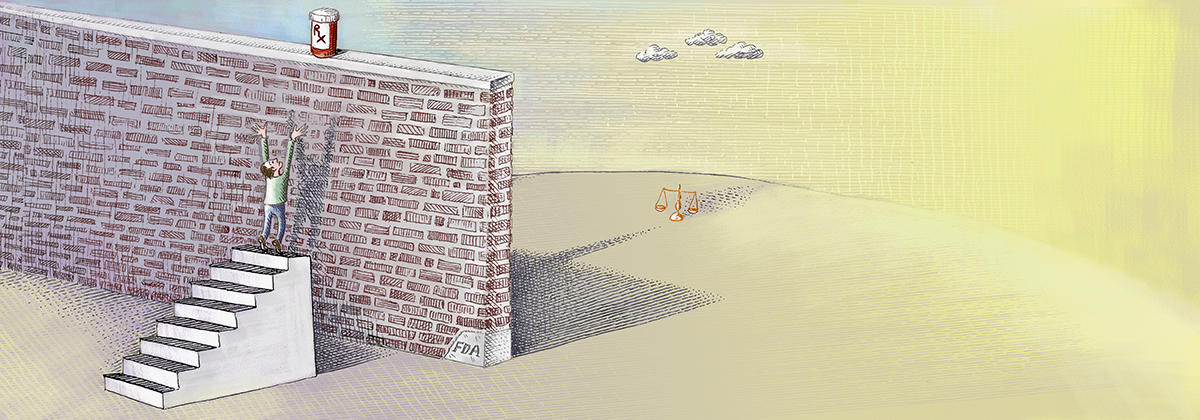

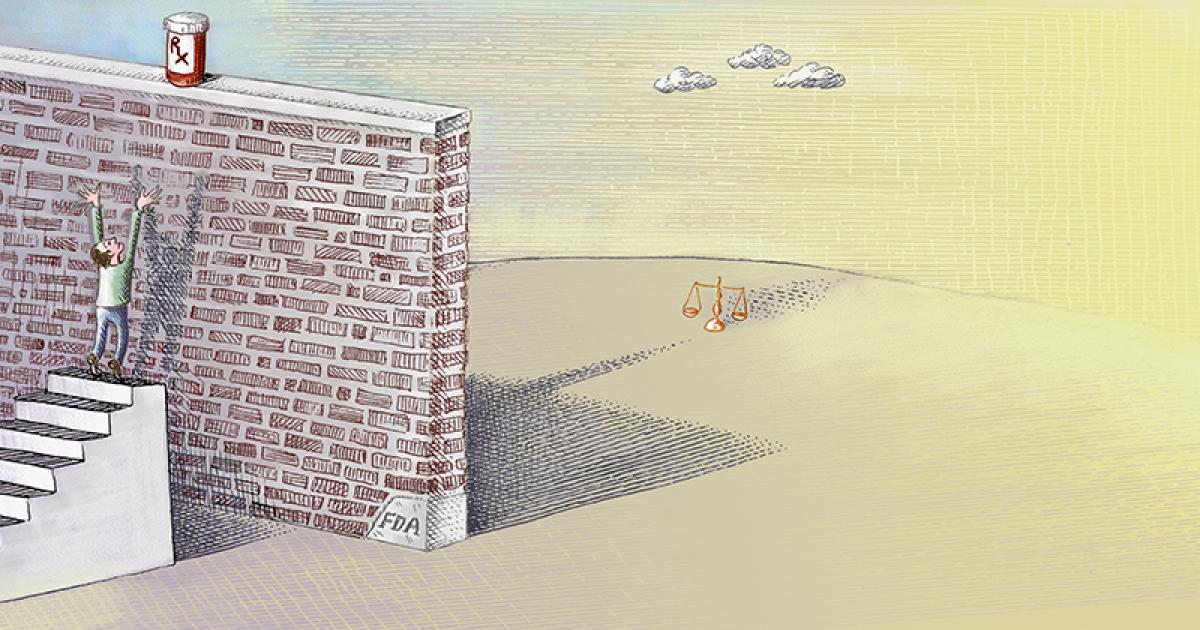

A measure beginning to sweep through the states is offering new hope to patients with terminal diseases and their loved ones. Called “Right to Try,” the statutes establish the right of terminally ill patients to access certain experimental drugs prior to final approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). For many people, Right to Try can make the difference between life and death.

Nearly everyone has a loved one who has suffered a terminal illness. Their instinct is to fight, to find a cure or at least a way to extend life. The amazing leaps and bounds of medical technology often fuel that hope. But too often, our government places obstacles in the path of making the hope a reality.

A few years ago, Paulina and Jason Morris were at their 10-year-old son Diego’s soccer practice when he fell and complained about leg pains. They took him to a hospital, which performed scans and other tests. The news was as devastating as it was unexpected: Diego was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a rare form of bone cancer. His life was in danger.

Though the doctors were able to pinpoint the problem, there was nothing they could do to cure it. Paulina and Jason began contacting doctors around the world to find help for their son. They learned that a treatment called mifamurtide was approved in Europe since 2009, but the FDA refused to make it available in the United States. Because Jason had family in England, they moved there and were able to secure access. Part of Diego’s leg was removed and replaced with a prosthetic as part of the treatment.

Today, Diego has been cancer-free for a year, but the medication he needs to prevent a relapse still is not approved by the FDA. Meanwhile, other children with similar diseases face a dismal fate unless their families have the resources to look for cures abroad.

The United States has the greatest medical technology in the world. Promising drugs and treatments are developed constantly. Something is seriously wrong when Americans have to leave the country to access potentially life-saving drugs and technologies—many of which are being developed in this country—or even worse, to not be able to have access to them at all.

The problem is the costly, cumbersome, and time-consuming FDA drug-approval process, which has greatly expanded both in scope and burdens since the agency’s creation over a century ago. In 1962, the average FDA approval time for new drugs was seven months. Today it can take more than a decade and cost as much as a billion dollars or more.

FDA drug approval encompasses three phases. The first is safety. The second and third involve clinical trials of effectiveness. Clinical trials are limited in number and available only to individuals who meet strict criteria—for instance, they may have to be at a certain stage of illness. Nearly half of all cancer patients attempt to enroll in clinical trials, yet fewer than 3 percent of patients with terminally ill cancer patients are eligible. Even among the handful of eligible participants, many are given placebos rather than the actual treatments in order to promote testing efficacy.

The FDA has a “compassionate use” process that allows individual patients access to certain experimental drugs. However, the process requires doctors to complete over 100 hours of paperwork—for a single patient—and the approval process is cumbersome. Few patients have the time or money to go through it. Last year, fewer than 1,000 Americans obtained experimental medication through the compassionate use process.

It is impossible to quantify precisely how many people die during the FDA approval process of drugs that could have saved their lives, but any number is too many. Recently, the FDA approved the drug Gazyva, which substantially reduces deaths from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, the most common type of leukemia diagnosed in adults. Because the drug was so promising, the FDA “fast-tracked” approval—which still took seven years. During that time, 30,000 people died from that single disease.

The widely acclaimed Hollywood film Dallas Buyers’ Club focused national attention on regulatory barriers the FDA has erected between promising drugs and the patients who desperately need them. But efforts at the federal level to reform and streamline the FDA’s drug approval process repeatedly have failed.

Right to Try shifts the reform focus to the states and reverses the presumption that potentially life-saving drugs should be available only after federal bureaucratic dictates have been satisfied. Developed by the Goldwater Institute, Right to Try gives terminally ill patients the right to access drugs prescribed by their doctors that have satisfied phase I—the safety phase—of the FDA approval process, so long as the manufacturer is conducting clinical trials.

The idea transcends partisan and ideological lines. The Goldwater Institute this year brought the idea to three states—Colorado, Missouri, and Louisiana—and it was approved by the legislatures in all three unanimously. Meanwhile, the Arizona Legislature voted to refer Right to Try to the November 2014 ballot, and Right to Try measures also have been introduced in Delaware, Michigan, and New Jersey.

Critics insist that states have no power to protect their citizens’ right to try by circumventing FDA processes. Generally speaking, laws that are encompassed within the federal government’s constitutional authority pre-empt conflicting state laws. The FDA has established broad hegemony over medications. Can’t the FDA simply wipe Right to Try off the books?

Not necessarily. One of the most exciting features in American constitutional law is that under our system of federalism, enshrined in the Tenth Amendment, the states retain broad authority to protect the rights of their citizens. In recent years, the U.S. Supreme Court has often narrowly construed federal statutes to avoid conflicts with state laws in areas that traditionally have been entrusted to state and local control, such as health care and education.

In the most analogous case, the Court in 2006 upheld Oregon’s “Right to Die” initiative against a federal pre-emption challenge. Attorney General John Ashcroft argued that the state law was pre-empted by the Federal Controlled Substances Act. In a 6-3 decision, the Court narrowly construed the federal law, acknowledging that regulation of medicine is traditionally entrusted to the states.

Indeed, states are free to go beyond the federal Constitution in guaranteeing rights to their citizens. Right to Try is the most recent in a series of efforts designed to create a “federalism shield” against abuses by the federal government. Two other Goldwater Institute proposals have been widely adopted. The Health Care Freedom Act protects the right of individuals to choose their own doctors and to not be forced to participate in a health insurance system. It was used by states to give them standing to assert their citizen’s rights in challenges to Obamacare. Several states also have adopted Save Our Secret Ballot, which protects the right of workers to decide by secret ballot whether to organize unions. A pre-emption challenge by the National Labor Relations Board against Arizona’s secret-ballot protection was rejected in federal district court.

The overwhelming bipartisan support for Right to Try is also likely to generate a political tsunami that it will be difficult for the FDA to ignore. The Obama Administration recently dropped its efforts to challenge state laws authorizing marijuana use. Support for Right to Try is even greater. If Arizona voters approve Right to Try this November, and other states follow suit next year, it may be politically difficult for the administration to take them on—and it also could inspire long-overdue congressional action to reform the system.

But an important question remains: will physicians and drug companies make potential cures available and thereby possibly invite the FDA’s wrath?

One pharmaceutical company that plans to do so is Neuralstem. It has developed a highly promising treatment for amyotrophic lateral scleroris (ALS), the devastating malady known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. The complex treatment, which involves injection of stem cells into the gray matter of the patient’s brain, has passed FDA phase I approval. Only 15 patients will participate in the second phase, which will take 18 months.

One of Neuralstem’s phase 1 participants was Ted Harada, a former Fed Ex worker who first experienced ALS symptoms in 2009 when he was playing in a swimming pool with his kids. After Harada received injections, the disease dramatically reversed course. He is now able to walk without a cane and completed a 2.5-mile walk to raise money to fight ALS. Harada still has the disease and could benefit from additional treatments. But ironically, he is ineligible to participate in phase 2 clinical trials because he does not fit within the applicable time parameters relating to when he contracted the disease.

Not surprisingly, Harada has become an activist for reform of the FDA’s process. “I’d suggest your paternalistic approach puts patients in more harm’s way than it does to protect them,” he testified at a recent FDA hearing. “Patients diagnosed with fatal diseases should be given the opportunity to take elevated risks with informed and educated consent in regards to their treatment options.”

Neuralstem’s CEO, I. Richard Garr, wants to make the treatment available now to the thousands of people who suffer from ALS. He hears constantly from terminally ill patients who would like to receive treatment. But average life expectancy is between two to five years after diagnosis, so Garr knows most of them will die before final FDA approval.

Right to Try will give them a chance to save their lives. At the same time, those experiences will yield real-world information about the treatment’s life-saving prospects, separate and apart from the rarified atmosphere of clinical trials.

Sadly, an agency that was tasked with approving drugs that can save lives now stands as an obstacle to that very mission. The federal government’s predictable failure to reform itself shifts the focus to the states. The genius of federalism is that power is devolved to governments closest to the people, who are capable of action even when the national government is not. In the case of Right to Try, federalism may turn out literally to be a lifesaver.