- Health Care

- World

- Military

- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

In less than eight years the nations of Europe and North America will mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. For the people of the United States this occasion will evoke images of terrible battles, valiant soldiers, and Flanders fields where poppies grow. It will also remind some Americans of August 1914, the grim, chaotic month when the independent kingdom of Belgium courageously resisted an invading army, only to fall victim to a four-year ordeal of conquest.

One American who will be forever linked in history with Belgium’s travail in that awful war is Herbert Hoover. After the Battle of the Marne, giant European armies bogged down in the trenches and famine threatened beleaguered Belgium, a highly industrialized nation of seven million people dependent on imports for three-quarters of its food. On one side, the German army of occupation refused to take responsibility for feeding the civilian population. Let Belgium import food as it had done before the war, said the Germans. On the other side stood the tightening British naval blockade of Belgian ports. Let the Germans, as occupiers of Belgium, feed its people, said the British. Besides, they argued, how could one be sure that the Germans would not seize imported food for themselves?

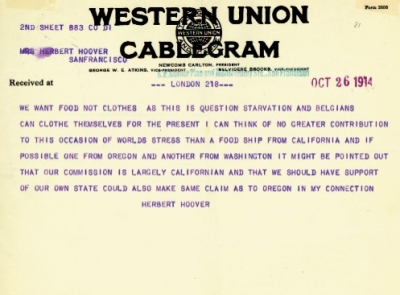

As the tense days passed in the early autumn of 1914, food supplies inside Belgium dwindled ominously. To the outside world went emissaries pleading for the Allies to permit food to filter through the naval noose. Finally, on October 22, after weeks of negotiation, Hoover established a neutral organization under diplomatic protection to procure and distribute food to the Belgian people. Great Britain agreed to let the food pass unmolested through its naval blockade. Germany, in turn, promised not to requisition this food destined for helpless noncombatants.

Why Hoover? In the summer of 1914 he was a prosperous, 40-year-old, international mining engineer living in London—and dreaming of a career of public service in the United States. This orphaned son of an Iowa blacksmith had come far indeed from his humble beginnings in the Midwest. Rising rapidly in his chosen profession, by 1914 he directed or in part controlled a worldwide array of mining enterprises that employed a hundred thousand men. “If a man has not made a fortune by 40 he is not worth much,” Hoover had said, while still in his 30s. By August 1914 he had achieved his goal yet was not content. “Just making money isn’t enough,” he confessed to a friend. Instead he wanted, as he put it, to “get into the big game somewhere.”

| After the Battle of the Marne, giant European armies bogged down in the trenches, and famine threatened beleaguered Belgium, a highly industrialized nation of seven million people dependent on imports for three-quarters of its food. |

His opportunity came in a form he could not have

predicted. In the first tumultuous weeks of the war, tens of thousands of American travelers in Europe fled the Continent for the comparative safety of London—and, they hoped, passage home. Arriving in the British capital, many Yankee tourists found themselves unable to cash their instruments of credit or obtain temporary accommodation, let alone tickets for ships no longer crossing the Atlantic. Responding to the travelers’ panic and lack of necessities, Hoover and other American residents of London organized an emergency relief effort that provided food, temporary shelter, and financial assistance to their stranded fellow countrymen. Eventually the passenger ships resumed their sailings, and more than 100,000 weary travelers headed back to the United States. Hoover’s efficient leadership during the crisis earned him the gratitude of the American ambassador to Great Britain, Walter Hines Page. And when a few weeks later the plight of Belgium became perilous, Ambassador Page and others agreed on Hoover, a man of demonstrated competence, to administer this new mission of mercy.

And so began an undertaking unprecedented in world history: an organized rescue of an entire nation from starvation. Initially no one expected this humanitarian task to last more than a few months. Few foresaw the gruesome stalemate that would develop on the Western Front. As Hoover himself later wrote, “The knowledge that we would have to go on for four years, to find a billion dollars, to transport five million tons of concentrated food, to administer rationing, price controls, agricultural production, to contend with combatant governments and with world shortages of food and ships, was mercifully hidden from us.”

| Eager for a fortune though he was, “Just making money isn’t enough,” Hoover confided to a friend. He wanted to “get into the big game somewhere.” |

Within a few months Hoover and a team of mostly American volunteers built up what one British government official called “a piratical state organized for benevolence.” Indeed, the novel relief organization, which went by the name of the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), possessed some of the attributes of a government. It had its own flag, it negotiated “treaties” with the warring European powers, and its leaders parleyed regularly with diplomats and cabinet ministers in several countries. It even had a “pirate” leader in Hoover, who enjoyed informal diplomatic immunity and traveled freely through enemy lines. He was probably the only American citizen permitted to do so during the entire war.

As a historian and biographer of Mr. Hoover, I am particularly impressed by four aspects of his wartime service to the people of Belgium.

THE IMMENSE TASK

First, today we take for granted the prompt intervention of humanitarian agencies in areas of distress. In 1914, however, no institution for the succor of Belgium existed. It became Hoover’s awesome responsibility to create one.

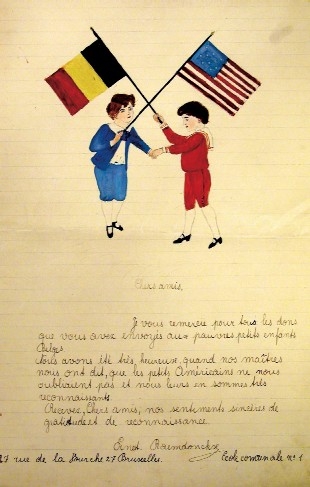

Consider the array of tasks that the Commission for Relief in Belgium was obliged to perform. First, it had to raise money throughout the world—partly through charitable appeals but primarily, as the war went on, through subsidies from the Allied governments. With this money it had to purchase wheat and other foodstuffs from North America, South America, and Australia. Then it had to arrange for shipping these foodstuffs to Belgium; eventually the CRB had a fleet of several dozen ships continuously at its disposal. When these ships entered the European war zone, they were required to navigate carefully lest they be seized or subjected to submarine attack. And when the food-laden vessels reached the neutral Dutch port of Rotterdam, their cargo had to be unloaded for conveyance by canal into Belgium.

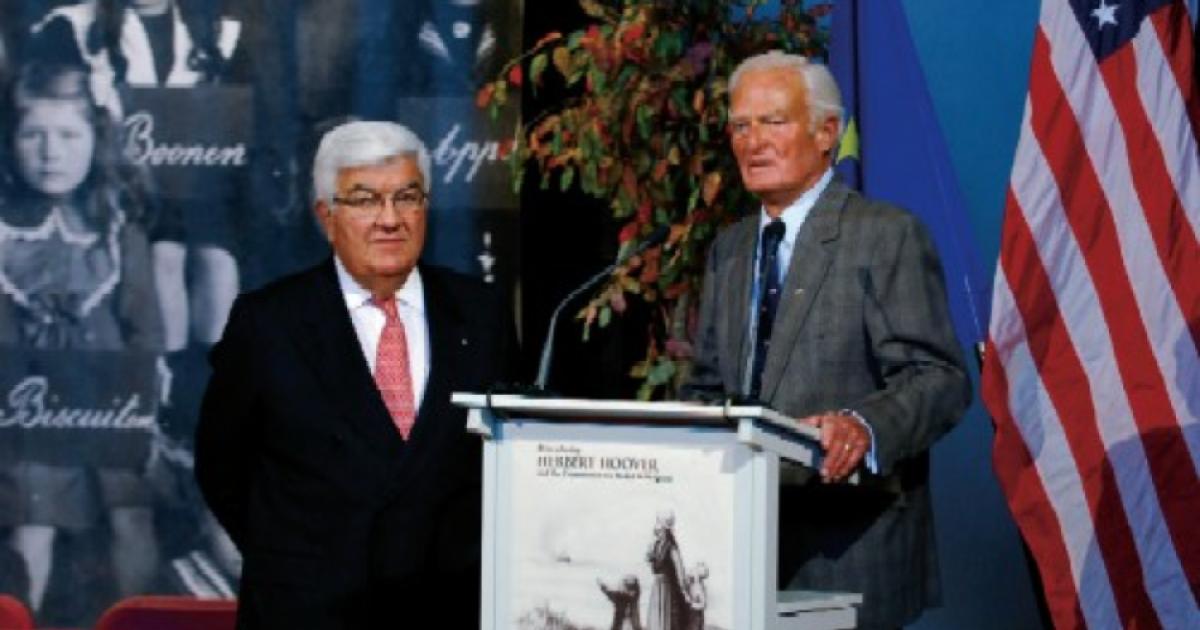

Once inside the occupied country the supplies had to be prepared for consumption in mills, dairies, and bakeries. Then the food had to be distributed equitably to an anxious population scattered over more than 2,500 villages, cities, and towns. As part of its undertaking, the CRB needed to verify that the daily rations did indeed reach their intended recipients and not the German army of occupation. Working with Hoover and his staff was a vast network of 40,000 Belgian volunteers who handled the distribution of food throughout their land. This parallel Belgian organization, known as the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation, was headed by some of the country’s most eminent business leaders. In early 1915, Hoover’s team was allowed to extend its life-sustaining operations to two million desperate French civilians caught behind the German battle lines on the Western Front. Thus the CRB’s work came to encompass a total area of nearly 20,000 square miles.

PRESSED FROM EVERY SIDE

No enterprise so massive, so multifaceted, so exposed to the passions of war, could hope to function undisturbed. Pressures and troubles beset Hoover at every turn. From the day of its inception, the CRB had to cope with critics in the various belligerent governments who were convinced that its work was enhancing the military strength of one side or the other. Scarcely a month went by that did not witness some challenge to the precarious existence of the commission. Time and again Hoover became embroiled in exhausting negotiations in an endless race against famine and malnutrition. At times, too, he had furious disagreements with his Belgian counterpart, Emile Francqui, a man, like himself, of great ability and formidable force of personality.

Sometimes, weary from incessant conflicts with one or another belligerent power, Hoover considered resigning. “Were it not for the haunting picture in one’s mind of all the long line of people standing outside the relief stations in Belgium,” he wrote early in the war, “I would have thrown over the position long since.” But Hoover did not quit. Ultimately it was his critics who yielded, recognizing his indispensability, his growing stature, and the risk of angering American public opinion that he had so skillfully mobilized.

“THE CHIEF” OF THE VOLUNTEERS

Third, I continue to be impressed—as were so many observers at the time—by the energy, resourcefulness, and public-relations acumen of the man at the apex of the CRB. Although the relief commission had many volunteers—all, like Hoover, working without pay—and although Hoover himself emphasized the value of organization, his loyal subordinates knew that one man dominated their endeavors: the man they called “the Chief.”

What kind of a person was he? Here is a description of him by an acquaintance in this period, Edward Eyre Hunt:

In appearance he is astonishingly youthful, smooth-shaven, dark haired, with cool, watchful eyes, clear brow, straight nose, and firm, even mouth. His chin is round and hard.

One might not mark him in a crowd. There is nothing theatrical or picturesque in his looks or bearing. . . . At work he seems passive and receptive. He stands still or sits still when he talks, perhaps jingling coins in his pocket or playing with a pencil. His repertory of gestures is small. He can be so silent that it hurts.

Being an American he sometimes acts first and explains afterwards. But his explanations, like his actions, are direct and self-sufficient.

He was indeed a man of determination and force. Emile Francqui called him une mâchoire (jaw).

When the United States entered the European conflict in 1917, Hoover returned home to head a new wartime agency, the United States Food Administration. But the relief commission that brought him fame continued to function, although in a reorganized form necessitated by the end of U.S. neutrality. Throughout the war the CRB and the Comité National indefatigably fed more than nine million people a day in Belgium and northern France. And when the commission finally closed its accounts, it found that it had spent nearly a billion dollars sustaining the health and morale of the Belgian people. It had made Herbert Hoover an international symbol of practical idealism and had launched him on what he later called “the slippery road of public life.” In Belgium King Albert conferred upon him a specially created, unprecedented title: “Ami de la nation belge,” friend of the Belgian nation.

FIRST STEP TOWARD GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY

Finally, the creation of the Commission for Relief in Belgium turned out to be more than a passing episode in a great war—and more than a springboard to one man’s political career. Hoover’s endeavor was in fact a pioneering effort in global philanthropy—a forerunner of the great network of transnational, nongovernmental organizations with which we are familiar today. As Hoover himself proudly declared in a speech in Brussels in 1958, his unprecedented Belgian relief organization had brought “lasting benefits” to the world. It had “pioneered the methods of relief of great famines,” and it had developed a “system” for “maintenance and rehabilitation” of children during war and other social upheavals.

| “The knowledge that we would have to go on for four years, to find a billion dollars, to transport five million tons of concentrated food, to administer rationing, price controls, agricultural production, to contend with combatant governments and with world shortages of food and ships, was mercifully hidden from us.” |

The CRB was also pioneering in another respect: It was the first great institutional embodiment of a new force in twentieth-century politics: American altruism in the form of humanitarian relief missions and foreign-aid programs. Hoover himself later described the CRB and his other relief enterprises as an “American epic,” and he was not alone in thus assessing their significance. In 1916 Lord Eustace Perry of the British Foreign Office described Hoover as “the advance guard and symbol of the sense of responsibility of the American people towards Europe.”

In more recent times the world has grown accustomed to American action to save lives and restore the fractured economies of far-off lands. Indeed, today such involvement is almost universally taken for granted. One reason for this expectation, one reason for its acceptance, is the institution created nearly one hundred years ago by Herbert Hoover.

For Hoover, the Belgian experience was but a prologue. In the years 1917 to 1921, he as well as his country moved even more prominently onto the international stage. No longer just the almoner of Belgium, in 1918 and 1919 he became (in the words of General John J. Pershing) “the food regulator for the world.” He was acclaimed as a “Master of Efficiency.” An admiring American called him a “Napoleon of Mercy.” There was truth in this label. Between 1914 and 1923, more than 80 million people in more than 20 nations received food allotments for which Hoover and his associates were at least partly responsible. To put it another way, between 1914 and 1923, Hoover was responsible for saving more lives than any other person in history.

Why did he do it? An autobiographical statement that he composed sometime during World War I provides an important clue:

There is little importance to men’s lives except the accomplishments they leave to posterity. What a man accomplishes is of many categories and of many points of view; moral influence, example, leadership in thought and inspiration are difficult to measure . . . and the proportion of success to be attributed to their effort is always indeterminate. In the origination or administration of tangible institutions or constructive works men’s parts can be more certainly defined. When all is said and done accomplishment is all that counts.

During his lifetime Hoover created and administered many “tangible institutions,” the most remarkable of which was the Commission for Relief in Belgium. He wanted this institution to be remembered, and so it continues to be. But institutions, we know, are not impersonal beings; they are animated by the spirit of their founders. Today we celebrate not only an institution and its legacy but also the dedicated individuals—both Belgian and American—who sustained its constructive work and mitigated the horror of war. Men like Albert, king of the Belgians. Emile Francqui and the volunteers of the Comité National. The volunteers of the Commission for Relief in Belgium. And, in the vortex of this magnificent effort, that indispensable American benefactor, Herbert Hoover: ami de la nation belge.