- World

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- State & Local

- California

- History

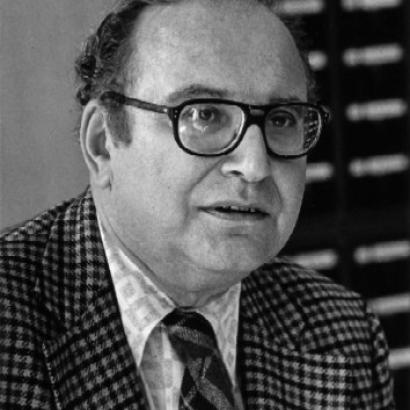

To understand a nation’s character, it seems to help to be a foreigner: Who has understood the American character better than the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville? Seymour Martin Lipset,

who died December 31, was not a foreigner or even, quite, an immigrant: He was born a year after his parents emigrated from Russia, in the few years after World War I and before restrictive immigration laws went into effect. Born in Harlem, raised in the Bronx, he attended City College of New York—a background, he once noted, that he shared with Colin Powell, except that Powell joined ROTC and Lipset joined the Trotskyite Young People’s Socialist League. His parents wanted him to become a dentist, but he was interested in other things—like why the rest of America was not as favorable to socialism as so many of his peers at CCNY.

He started off by looking at exceptions to the American—or, rather, North American—rule. His doctoral thesis and his first book, published in 1950, was Agrarian Socialism, on the Social Credit Movement in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. Through a long career, he kept an eye on Canada, as an interesting test case of a former British colony that has taken a different course; he contrasted the United States and Canada in Continental Divide in 1990. Another early subject was Union Democracy, a study of the International Typographical Union. At Columbia, Berkeley, Harvard, Stanford, George Mason, the Hoover Institution, the Woodrow Wilson Center, the Progressive Policy Institute, and the American Enterprise Institute, he straddled the disciplines of political science and sociology; he was the only person to head both the American Political Science Association and the American Sociological Association.

| “There can be little question that the hand of providence has been on a nation which finds a Washington, a Lincoln, or a Roosevelt when it needs him,” he once wrote. |

In 1960, he published the classic Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics, which became a standard text and sold more than 400,000 copies. Three years later came The First New Nation, an analysis of the uniqueness of America. Later books covered student politics, right-wing extremism, the politics of professors, public confidence (or lack of it) in institutions, and the place of Jews in American life. Altogether he wrote or coauthored 21 books, edited 25 books, and wrote hundreds of scholarly articles. His work was cited more often than that of any other contemporary political scientist or sociologist; type his name in Amazon.com and you come up with 3,105 entries.

Marty Lipset was a formidable scholar, developing new ways of quantifying behavior, but he was far from unapproachable. He was generous in training hundreds of graduate students and encouraging them to publish their work. In conversation and interviews he showed a sure command of scholarly articles on every subject even remotely relevant to his work and rattled off statistics with aplomb. He was a tall, imposing man, with a gentle demeanor and more than occasional flashes of humor.

Lipset’s life work, said historian John Patrick Diggins, was to “explain America to itself”—he was Tocqueville’s heir. And to explain our many particularities and peculiarities: why, as journalist Martin Walker put it, Americans exhibit almost Iranian levels of religiosity, and why they hate turning out to vote but enjoy joining voluntary associations. He appreciated the role of religion in shaping the national character. “The United States is the only Protestant sectarian country in the world,” he told an interviewer in 2000, “and Protestant sectarians are very moralistic and believe that one should do what’s right, not what other people want.” But he didn’t see America through rose-colored glasses. He noted that treaties with Indians were routinely broken, “not by the government but by local settlers,” and—with a glance northward—that after Custer’s defeat, “the Sioux, who had wiped out an American battalion, went across the border and surrendered to six Mounties! The reason they did so was that they knew the Queen’s treaties were kept.”

| Lipset pondered why Americans exhibit almost Iranian levels of religiosity, and why they hate turning out to vote but enjoy joining voluntary associations. |

Like many of his comrades at City College, Marty Lipset moved to the right politically over the years, though never to the Republican Party. But he was less interested in spirited persuasion than in clear-eyed perception. He recognized that America’s strengths were also its weaknesses. “I view the organizing principles and institutions of the United States as doubled-edged,” he wrote in American Exceptionalism, published in 1996 and perhaps the summa of his work, “that many negative traits that currently characterize the society, such as income inequality, high crime rates, low levels of electoral participation, a powerful tendency to moralize which at times verges on intolerance toward political and ethnic minorities, are inherently linked to the norms and behavior of an open democratic society that appear so admirable.” And he realized that the success of democratic government depended not only on institutional design but also on great leaders—“independent variables,” in political-science language—which America has been exceptionally lucky in having.

“There can be little question that the hand of providence has been on a nation which finds a Washington, a Lincoln, or a Roosevelt when it needs him,” he wrote. And then he added, “When I write the above sentence, I believe that I draw scholarly conclusions, although I will confess that I write as a proud American.” No one has done as good a job at explaining America to itself as Tocqueville did in the century before last. But few if any have come as close as Marty Lipset did in the century just ended.