by Stephan Kieninger, Hoover Library & Archives Silas Palmer Fellow 2016

Abstract1

On 2 August 2019, the United States formally withdrew from the INF Treaty. In 2017, Russia had begun deployment of the treaty-noncompliant cruise missile now known as the SSC-8. George Shultz and Mikhail Gorbachev have called American and Russian decision makers to preserve the INF Treaty as a pillar of nuclear arms control.2 More than thirty years ago, they stepped forward with President Reagan to change history’s direction. They found an unprecedented agreement to eliminate all U.S. and Russian missiles between the ranges of 500 to 5500 kilometers. The two countries destroyed a total of 2,692 ballistic and cruise missiles by the treaty’s deadline of June 1, 1991, with verification that had not been imagined as possible before.

This paper looks into George Shultz’s key role on the road to the INF Treaty emphasizing the importance of his focus on process and personal diplomacy. The article does not recite the whole history of U.S.-Soviet arms control negotiations, rather it investigates some of Shultz’s key interventions in the policy realm. First, starting in 1982, Shultz initiated the search for a broader U.S.-Soviet dialogue and the establishment of working relations on which US and Soviet decision makers could rely in times of crisis. Shultz thought that emphasis on process instead of geopolitics and linkage would make it possible to establish a sustainable framework for nuclear arms control. Second, NATO’s 1983 deployment of Pershing II and Cruise Missiles signaled strength and NATO’s willingness to match the Soviet Union’s buildup in Intermediate Nuclear Forces. Shultz saw that the path to the INF Treaty had to begin with an arms buildup as the Soviet Union was not prepared to reduce its SS-20 INF deployments. Shultz emphasized that NATO had stick to its familiar two-track diplomacy: The Alliance needed both a firm defence and the willingness to see a constructive relationship with the Soviet Union emerge. Strength and diplomacy went together.

Third, starting in 1985, George Shultz played a pivotal role in Ronald Reagan’s and Mikhail Gorbachev’s nuclear summitry. Shultz practiced arms control diplomacy as a continuous confidence-building exercise. He helped Reagan and Gorbachev to establish an upward spiral of trust by creating positive experiences with each other. Both reconceptualised the notion of “security:” Reagan believed that Soviet communism was not the main enemy, he argued, nuclear weapons were. Reagan and Gorbachev sought to move from mutually assured destruction to mutually assured survival. Fourth, the paper looks into George Shultz’s successful management of NATO’s internal arms control discussions. The U.S.-Soviet INF negotiations had enormous impact on European security: The INF Treaty lowered the threat of nuclear war in Europe substantially and paved the way for negotiations on tactical nuclear and chemical weapons, as well as negotiations on conventional forces in Europe.

Getting the Process Started. George Shultz and the Move from Linkage to Engagement

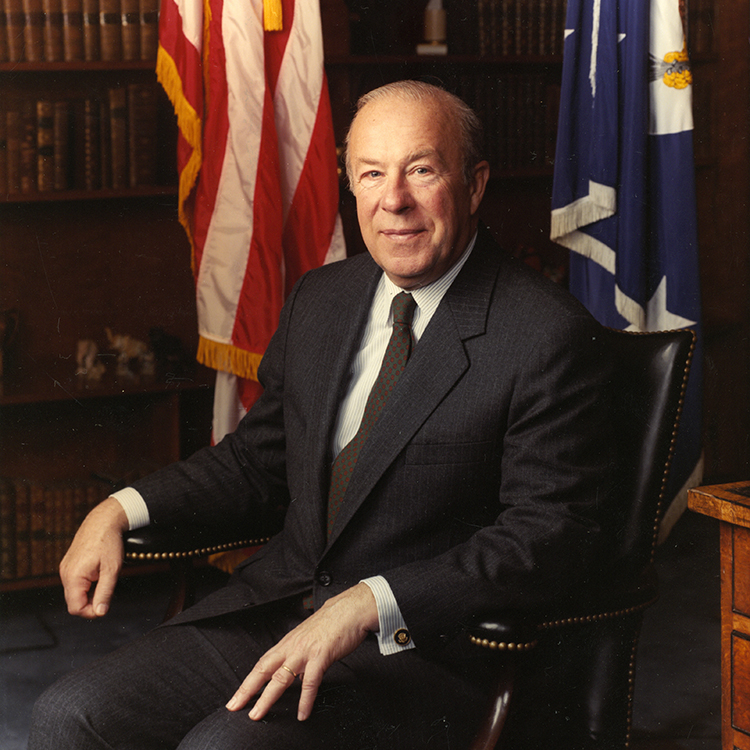

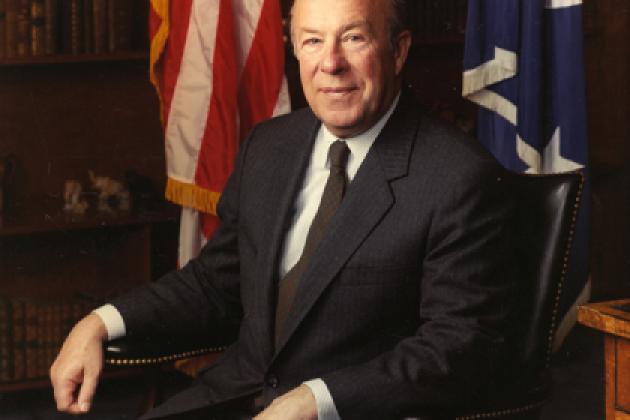

George Shultz is an extraordinary public servant with a unique career in academia, business and politics. He used to be a Professor of Economics at Chicago University, he served as CEO of Bechtel Group and had four cabinet-level government positions in the Nixon and Reagan Administrations. His tenure at Secretary of State literally brough the Cold War to a close, and he played a major role in it. His nuclear arms control policy facilitated the conclusion of the landmark INF Treaty in 1987. Which human characteristics drove his policy? Why was George Shultz able to play such a crucial role in nuclear diplomacy? Which personal characteristics shaped his policy choices? Which personal traits distinguish George Shultz from other policy makers?

It is important that George Shultz is not a geopolitics-oriented figure like his Republican predecessors Henry Kissinger and Alexander Haig. Shultz thought more in terms of people and their interests than in abstract terms like nation and states and how they seek to maximize power in the international system. In his memoirs, Shultz stressed the relevance of his economics training providing a system for analyzing problems. “My training in economics has had a major influence on the way I think about public policy tasks, even when they have no particular relationships to economics,” Shultz wrote. “Economic policies are partially anticipated and continue to affect the economy long after they have been put into place. The key to a successful policy is often to get the right process going.”3 This insight drove his arms control policy and his broader approach toward the Soviet Union focusing on process and trying to engage the Soviet Union in as many ways as possible and to move forward in steps. The theory was that the experience of solving small problems would make it easier eventually to solve big ones. Back in the 1960s, this philosophy had guided Kennedy’s strategy of peace and Lyndon Johnson’s peaceful engagement approach toward the Soviet Union. The objective had been to search for a more attainable peace in the shadow of the Vietnam War.4 The conclusion of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1968 had proved the feasibility of Johnson’s engagement policy: Vietnam did not stand in the way of arms control.5 George Shultz was creative and determined to re-engage the Soviet Union in times of crisis. He believed that the global Cold War and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan must not stand in the way of the INF Treaty. Shultz initiated the search for a new structure of peace sensing the need for a broader strategic dialogue and the establishment of working relations on which US and Soviet decision makers could rely in times of crisis – “realistic reengagement” was his theme.6 Shultz practiced arms control diplomacy as a continuous confidence-building exercise. “Trust is the coin of the realm,” he used to say.7

The combination of dialogue and deterrence was the key feature of Shultz’s arms control diplomacy. Time and again, Shultz emphasized that NATO had stick to its familiar two-track diplomacy: The Alliance needed both a firm defence and the willingness to see a constructive relationship with the Soviet Union emerge. Strength and diplomacy went together: “If you go to a negotiation and you do not have any strength, you are going to get your head handed to you. On the other hand, the willingness to negotiate builds strength because you are using it for a constructive purpose. If it is strength with no objective to be gained, it loses its meaning. […] These are not alternative ways of going about things,” Shultz thought.8

NATO’s dual-track decision of December 1979 reflected the parallelism between strength and diplomacy. NATO offered the Warsaw Pact a mutual limitation of medium-range ballistic missiles and intermediate-range ballistic missiles combined with the threat that in the event of disagreement NATO would deploy additional weapons in Western Europe. The decision was based on the premise that the path to sustainable arms control had to begin with an arms buildup. Deployment and negotiations were intertwined.9 NATO would not get one without the other. Ronald Reagan championed the so-called zero option, that is the complete removal of Intermediate Nuclear Forces on both sides. He saw it as the ideal outcome as it would remove all the Euromissiles rather than simply controlling their growth in balanced ways. The U.S. proposal foresaw that the Soviets would take out all their deployed SS-20 missiles and NATO would not deploy any Intermediate Range Forces.10

The challenge for the Reagan Administration was to stick to NATO’s zero-zero approach at a time when the Soviet Union proposed various sort of agreements in order to keep its SS-20 missiles. In January 1982, for instance, Soviet Foreign Minister Gromyko suggested an agreement to establish an eventual ceiling of 300 intermediate-range missiles and nuclear-capable aircraft Europe for each side.11 Both sides were exploring opportunities for a proposal in between zero-zero. In July 1982, the American and Soviet arms control negotiators Paul Nitze and Yuli Kvitsinsky developed an informal package of elements to be included in a possible INF agreement. Their so-called “Walk in the Woods” proposal called for: equal levels (75) of INF missile launchers in Europe adding up to 300 warheads for the United States and 225 for the Soviet Union (because U.S ground-launched cruise missiles had four warheads and the Soviet SS-20 had three); no deployment of U.S. Pershing IIs; a limit of 90 on Soviet SS-20 deployments in the Asian part of the Soviet Union.12 Eventually, the Soviets rejected the “Walk in the Woods” package in September 1982.

The challenge for the Reagan Administration was to install Pershing II and Cruise Missiles in 1983 against the backdrop of the nuclear freeze protests in the United States and Western Europe. NATO was determined to show resolve: If the Soviets did not remove their missiles, NATO’s deployment would go forward. West Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl was a crucial partner in this endeavor.13 After his election in October 1982, Kohl went to Washington assuring President Reagan that the Federal Republic would put up the missiles if there was no success in the negotiations. “We’ll do it,” he said, “even if I have to do it all by myself.”14 Kohl’s predecessor Helmut Schmidt had been a key proponent of NATO’s dual-track decision but was no longer able to implement it on account of protests within the Socialdemocratic Party. This led to his voting out of office. In contrast, Kohl’s Christian Democratic Party (CDU) endorsed NATO’s policy.

When Shultz came into office as Secretary of State in the summer of 1982, the economist in him asked: “Where are we trying to go, and what kind of strategy should we employ to get there?”15 At the start of his tenure, he saw the need for a new approach to U.S.-Soviet relations.16 Shultz abandoned the traditional linkage approach that had been the dominating element in US–Soviet relations since the days of Henry Kissinger. Kissinger’s assumption was that the United States could best influence and restrain Soviet policy by regarding the entire range of conflicts and contentious issues with the USSR not on their own merits but in their effects on U.S.-Soviet relations.17 Linkage in US–Soviet relations meant that bad things in one area would cause disruptions in all other areas. The linkage approach carried the danger that crisis and incidents might stay in the way of progress in areas of vital U.S.-Soviet interest: Linkage made it difficult to find progress. The global Cold War always threatened to undermine U.S.-Soviet cooperation.18 Jimmy Carter’s reaction to the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan was the most outstanding signal for the failure of linkage. Carter cut off almost all ties with the with the Soviet Union.19 U.S.-Soviet relations were almost non-existent, and Carter’s linkage approach strained NATO. The European allies were concerned about the lack of U.S.-Soviet leadership communication. Nuclear fear led to the emergence of nuclear protest movements.20

Shultz saw urgent need for revitalized U.S.-Soviet dialogue after Soviet General Secretary Brezhnev’s death and the frozen situation between Washington and Moscow.21 He fully shared German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt’s assessment that “the superpowers are not in touch with each other’s reality. The Soviets can’t read you. The situation is dangerous. There is no human contact.”22 Shultz began to work on the problem holding weekly meetings with the long-time Soviet Ambassador in Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin.23 Shultz called his approach “gardening:” He emphasized that “the idea was to get out little irritants so that they would not grow into unnecessarily major problems. My idea was: If you see a little weed, get it out before it turns into a real problem.”24

Shultz emphasized human relations at high levels of politics. He had a capacity to personalize diplomacy. He shared Helmut Schmidt’s concern that “partnership in security involves trust and predictability. For that reason, personal and direct contact between political leaders in indispensable.”25 Dialogue often tended to wane in crisis moments. George Shultz thought that it should be the other way around. Increased tensions necessitated more dialogue. Time and again, Shultz discussed U.S.-Soviet relations in Saturday strategy sessions with the Reagan Administration key foreign policy makers. In one of these meetings, Vice President Bush noted that “there is a public perception that we are not communication with the Soviets, and this makes the public uneasy. There is a need to convince the public that we are in fact communicating.” Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Lawrence Eagleburger emphasized that “our dialogue is like ships passing in the night. We must get into more discussion of fundamental questions.”26 Shultz’s own style of management was an important asset in this endeavor. Shultz’s leadership style was inclusive. He relied on the State Department’s talent and experience. In his memoirs, Shultz wrote that “I always have found that if I could create an environment around me in which everybody felt they were learning, I would have a hot group. I have always tried to include people in what I was doing, to encourage them to say what they think, to let them see the problems that were confronting us all, and to create an atmosphere in which everyone could feel at the end of the day, or the end of a week or a month, that he or she had learned something.”27

In January 1983, Shultz approached Reagan with a new strategy for intensified U.S.-Soviet dialogue. Shultz wanted to test the waters for an improvement in U.S.-Soviet relations arguing that “even if no improvement ultimately takes place, the dialogue itself would strengthen our ability to manage the relationship and keep the diplomatic initiative in our hands.” Shultz emphasized that bold initiatives were perhaps doomed to fail at this point. Rather, Shultz was eager to initiate a sustainable diplomacy and “a patient, steady, yet creative management of a long-term adversarial relationship with the Soviet Union.”28 Moreover, Shultz set out for the first time what was to become the Reagan Administration’s four-part agenda for U.S.-Soviet relations: human rights, arms control, regional issues, and bilateral relations. Shultz’s approach was down to earth: He wanted to maintain the overall framework the Reagan Administration had established believing it was important to address the full range of contentious issues including the Soviet Union’s military buildup, international expansionism, and human right violations. Shultz was determined to rebuild the U.S.-Soviet relationship based on some permanent ground rules of U.S.-Soviet behavior that had been previously established.

Shultz saw that President Reagan was much more willing to move forward in relations with the Soviet Union than his White House advisers had been anticipating so far. In February 1983, Shultz proposed to bring Dobrynin over to the White House for a private meeting. Shultz expected a brief conversation, but Reagan had thought a great deal about the encounter. The meeting lasted two hours, and Reagan engaged Dobrynin on all controversial issues arguing US positions across the board. Reagan pointed out that “he was talking about genuine content and not simply words of good feeling.”29 Afterward, Shultz and Dobrynin went back to the State Department and continued their conversation for another hour. Shultz sensed that Dobrynin “was clearly impressed with this development. He was surprised that it happened. […] He commented that it just might possibly have been a historic occasion – that whether we were talking about two years or six years, in either case it was quite possible to get things accomplished and that he would give [Soviet Secretary General] Andropov a full and detailed report on the entire conversation.”30 Reagan’s encounter with Dobrynin was a turning point in U.S.-Soviet relations.31

Shultz and Dobrynin found common ground by putting together an inventory of bilateral U.S.–Soviet agreements. Some of them had expired or had been cancelled after President Carter had terminated all contacts with the Soviet Union in the aftermath of the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan. In the spring of 1983, just a month after President Reagan had label the Soviet Union as an “evil empire” in public,32 Shultz suggested a renewal of the existing U.S.-Soviet cultural agreement and the opening of reciprocal consulates in Kiev and New York. In addition, Reagan authorized Shultz to intensify negotiations over a long-term grain agreement: Reagan’s public attacks on the Soviet Union and his evil empire speech went hand in hand with the emergence of his quiet diplomacy. Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy was contradictory. On the one hand, Reagan wanted America’s victory in the battle with the Soviet Union. At the same time, Reagan wanted to abolish nuclear weapons, and reducing nuclear weapons required patient statecraft and the relaunch of U.S.-Soviet cooperation. George Shultz managed to reconcile these potentially contradicting aims.

Strength and Dialogue go together. INF Deployment in Western Europe and Re-Engagement toward the Soviet Union

1983 was an important test case for the Reagan Administration’s statecraft. Was NATO willing to deploy Pershing II and Cruise Missiles in Europe? In January and February 1983, Vice President Bush went to Europe to discuss the status of the INF negotiations and the impending deployment of the Pershing II and Cruise Missiles. Bush emphasized the importance of NATO solidarity and the U.S. commitment to the zero-option, but also stressed that the U.S. would be flexible if the Soviets proposed verifiable reductions.33

On 30 March 1983, Ronald Reagan proposed an interim INF agreement to establish equal global levels of U.S. and Soviet warheads on INF missile launchers at the lowest possible number – between 50 and 450 warheads, with zero still the ultimate goal.34 However, the Soviet Union rejected the proposal. The Soviets were determined to prevent real progress in the INF negotiations hoping that NATO would not be willing to implement its INF deployments. In April 1983, Ronald Reagan told NATO Secretary General that “he was often frustrated at public perceptions that he was not committed to arms reductions. He emphasized the importance of Alliance support for the two track decision since the Soviets were unlikely to negotiate seriously until the Alliance was ready to make deployments.”35

In May 1983, the stalemate in the INF negotiations was a crucial issue during the World Economic Summit at Williamsburg. The summit declaration emphasized NATO’s serious willingness for negotiations and its determinedness to go forward with deployments if the Geneva talks failed. Chancellor Kohl pointed out that “the Soviet Union had been building up its armed forces and was now fuelling anti-Americanism. […] It was not enough simply to say that we are in favor of pace. It was all very well to use moderate language but it would be disastrous not to make the position of the West clear. The West should tell the Soviet Union that they were in favour of controlling armaments, but that the Soviet Union could not expect the West to stand still while they increased.”36 The G-7 firmly resisted Soviet attempts to drive a wedge between the United States and its West European allies. The Soviet Union played a wait-and-see game gambling on its ability to prevent INF deployment in Western Europe. NATO had to stick to its dual-track approach. In October 1983, George Shultz pointed out that “the NATO allies had a great deal to gain from successfully proceeding with both tracks of the 1979 decision. More than anything else, this would demonstrate the strength of the alliance and the ability of the NATO countries to implement a decision that they had taken together.”37 NATO’s unity and firmness eventually led to the deployment of Pershing II and Cruise Missiles starting in November 1983. George Shultz saw it as a turning point in the Cold War: “The Pershing moment” signaled strength – the Soviet Union was not able to break NATO’s solidarity.38

At the same time, Reagan’s nuclear diplomacy put emphasis on soft power. Time and again, George Shultz emphasized the relevance of values. He wanted to engage the Soviet Union in the battle of ideas stressing that “history is on our side. In terms of values, there is no contest between our system and theirs. We must emphasize values. The weapons are a means to an end, not an end in itself.”39 Ronald Reagan shared this view. Reagan was often considered to be a hawkish President. George Shultz realized that Reagan was not hawkish at all when it came to his views on nuclear weapons. Reagan saw nuclear arms as immoral. “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,”40 Reagan thought. Reagan’s long-term vision was a world free of nuclear-weapons. He cherished a desire to eliminate nuclear weapons entirely. Reagan’s nuclear abolitionism and his Strategic Defense Initiative grew out of his deeply rooted personal beliefs and religious views – SDI was his personal policy initiative. Reagan was discontent with the nuclear order. He was on the search for an alternative to replace the logic of deterrence and mutual assured destruction. Reagan saw two ways to rid the world of nuclear weapons: “One was by eliminating nuclear weapons; the other was to build a defense that would make them impotent and obsolete. Linking the two methods offered a way forward.”41 Reagan thought that 1984 was the right time for progress. George Shultz believed that “we should make a real effort to get something accomplished.”42

The Soviet Union’s leadership vacuum was a real problem. President Reagan quipped that the Soviets leaders kept dying on him. In February 1984, Brezhnev’s successor Yuri Andropov died from cancer. The selection of the debilitated Konstantin Chernenko as the new Soviet leaders was not the envisaged sign of a new departure. Against this backdrop, Shultz was determined to generate as much factors of balance and stability as possible: Whoever was to be appointed as Chernenko’s successor should be able to rely on reassuring rather than a threatening international background. At the same time, it was important to look beyond the old guard in Moscow. Jack Matlock of the National Security Council emphasized “the need to find ways to reach out to the younger Soviet generation more effectively, as we conduct our dialogue with the leaders.”43 For the time being, a broad expansion of U.S.-Soviet cooperation was the most promising means to achieve progress. Like Margaret Thatcher, Reagan believed that “we are more likely to make progress on the detailed arms control negotiations if we can first establish a broader basis of understanding between East and West. It will be a slow and gradual process, during which we must never lower our guard. However, I believe that the effort has to be made.”44

Reagan was still yearning for a one-on-one meeting with a Soviet leader. On 28 September 1984, he finally saw Andrei Gromyko for two hours in the Oval Office. Reagan talked all topics including human rights. Gromyko praised the benefits of Communism in near religious proportions. Both picked selective evidence to argue that the other side was seeking superiority. Reagan found Gromyko’s remarks outlandish. Yet, he believed that the common responsibility for peace counted more than the political differences. Right at the beginning of their conversation, Reagan pointed out that “our political systems are very different and […] we will be competitive in the world. But we live in one world and must handle our competition in peace.” Reagan’s aim to abolish nuclear weapons was uppermost on his agenda: “As the two superpowers”, he emphasized “we must take the lead in reducing and ultimately eliminating nuclear weapons.”45

Many in Reagan’s Administration did not share his vision. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger doubted that mutually-beneficial arms control with the Soviet Union were possible at all. He argued that “the Soviet Union has little interest in giving the President a victory. They would only give him an agreement for which he could not take credit. […] If we become too eager”, he warned, “the Soviet Union will sense weakness”. Ronald Reagan was determined to go ahead. He believed it was pivotal to convey willingness reiterating that “we can’t go on negotiating with ourselves. We can’t be supplicants crawling, we can’t look like failures.” Reagan acknowledged that it might take several months until the start of nuclear negotiations. Thus, he was determined to use U.S.-Soviet cooperation in all available issues areas as a precursor for arms reduction talks. He emphasized that “we will need to do lesser things, MBFR, chemical weapons, confidence building, notification of all ballistic missile tests, agreement not to encrypt, and EDC. But we shouldn’t let them off the hook on START and INF.”46

Reagan designated George Shultz to carry out his policy, and he wanted Shultz to be his public spokesman on arms control.47 However, the arms control skeptics within the Reagan Administration wanted to put an end to negotiations before they even started. Caspar Weinberger standard arguments was: “Now is very inappropriate for any proposal.” George Shultz wanted to start strategic arms reduction talks right away: “We have been around four years. What have we been doing?”48 Shultz believed that the United States was going to negotiate from a position of strength. Shortly after the 1984 Presidential election, word came of Moscow’s interest in resuming nuclear arms talks. On 17 November 1984, Reagan received a letter from Soviet Secretary General Chernenko calling for a new round of arms negotiations on strategic arms, space weapons and INF. Negotiations should even go further: “We are prepared to see the most radical solution which would allow movement toward a complete ban and, eventually, liquidation of nuclear arms,” Chernenko wrote.49 Neither Reagan nor his advisers believed in this part of Chernenko’s message. The Soviets had left the bargaining table fourteen months ago? Now they were proposing to get rid of all nuclear weapons? Was it possible to find a way to navigate to nuclear zero? This question greatly complicated U.S.-Soviet relations in Ronald Reagan’s second term. Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative was almost always the bone of contention. In January 1985, George Shultz told Andrei Gromyko that strategic missile defense, “if they proved feasible, could contribute to the goal of eventually eliminating all nuclear weapons.” The Soviets wanted Reagan to abandon SDI: Gromyko countered that it “would be used to blackmail the USSR.”50 In January 1985, it was not predictable at all that Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev would manage to break the impasse arresting the arms race.51 For the time being, it was important that NATO’s 1983 Pershing moment had paid off: It brought the Soviets back to the bargaining table.

Nuclear Summitry. George Shultz and the Reagan-Gorbachev Summits in Geneva and Reykjavik

George Shultz played a crucial role in this endeavor leading to the famous Reagan-Gorbachev summit diplomacy.52 Shultz was convinced that Mikhail Gorbachev was a new type of Soviet leader with a serious interest in nuclear arms control. Reagan and Shultz had long been looking for a young and promising Soviet Secretary General, one with whom they could conclude lasting arms control agreements. Brezhnev, Andropov, and Chernenko passed away in short order. Gorbachev was a promising member of the Politburo, and his December 1984 visit to London indicated he might be the next Secretary General. Back at the time, Margaret Thatcher confessed that she could sit down and “do business” with Gorbachev despite the fact that the was a committed Communist.53 In March 1985, George Shultz and Vice President George Bush attended Chernenko’s funeral and led initial talks with Gorbachev: Shultz sensed “a genuine change of generation in the Soviet leadership.”54 “Gorbachev and Shevardnadze were from a distinctly different mold. It was more than a difference in personality. Because this new generation of leaders from the provinces had dealt with real problems in the Soviet system, they might accept the fact that change was imperative,” Shultz thought.55 Reagan reached out to Gorbachev in order to build a relationship of trust: “I believe meetings at the political level are vitally important if we are to build a more constructive relationship between our two countries,”56 Reagan pointed out in one of his first letters to Gorbachev in April 1985. This attitude guided Shultz’s first personal encounter with Mikhail Gorbachev in November 1985 when Shultz travelled to Moscow for preparations of the first Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Geneva the same month. Arms control ranked high on the agenda. The key U.S.-Soviet argument arose over SDI. The Soviets wanted the Reagan Administration to abandon SDI holding progress on the INF and START negotiations hostage. But instead of discussing arms control right away, George Shultz decided to put aside ideology and global conflicts. Instead, Shultz decided to engage Gorbachev on the subject of the information age addressing the question of political and economic freedom as a key of growth and success. “Just look around,” he told Gorbachev, “the successful societies are the open societies,”57 Shultz said. Shultz’s creativity and the “classroom in the Kremlin” originated from his career in academia. Shultz’s out of the box thinking was aimed at overcoming the traditional approach of trading Soviet human rights concession against US concessions in trade. “I was groping for a way to get the Soviets to see that their own society would benefit from better treatment of individuals,”58 Shultz noted. Shultz’s fresh approach set an important precedent for his personal diplomacy with Gorbachev.

Shultz’s personal diplomacy with Soviet Foreign Minister Edvard Shevardnadze was another crucial factor for the success of his diplomacy. During their very first meeting in July 1985, Shevardnadze signaled the change in Gorbachev’s position on human rights. Whereas Gromyko had always rejected human rights as a Western policy of interference into the Soviet Union’s domestic affairs, Shevardnadze pursued an entirely new approach pointing out that “if we are to talk seriously about human rights, we need to talk about the need to live in peace; the right to life itself is the most fundamental right of all.”59 This change in attitude promised further opportunities for a lasting improvement in U.S.-Soviet relations, and Shultz was determined to use them. He envisaged his meetings with Shevardnadze as real conversations: He wanted Shevardnadze to abandon the old Soviet technique of reading long-drawn out prepared statements. Instead, Shultz was striving to have a real dialogue and a profound exchange of arguments. Thus, Shultz used their first meeting in July 1985 as way to introduce the technique of simultaneous translation instead of the traditional consecutive translation. It worked so well that Reagan and Gorbachev also came to use it. “This meant an opportunity for a real conversation, for a chance to connect the words with the eyes, the hands, and the body language of the speaker, for the possibility of interruptions and the kind of exchange that is possible when both people speak the same language,”60 Shultz noted.

Nevertheless, substantial problems remained. In November 1985, Gorbachev confronted Shultz with the Soviet arms control position: No reductions in offensive weapons unless the United States abandon SDI: “The Soviet Union will only compromise on the condition that there is no militarization of space,” Gorbachev said. “If you want superiority with your SDI, we will not help you. We will let you bankrupt yourselves. But we will not reduce our offensive missiles. We will engage in a buildup that will break your shield.”61 SDI also dominated the Geneva summit sessions between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in November 1985.62 Gorbachev’s objective was clear: He wanted a ban on space weapons as a precondition for reductions in strategic arms. Gorbachev had come to Geneva to end SDI. But Reagan did not waver. He pushed his personal vision of SDI arguing that “you cannot erase from men’s mind how to make these weapons, and even if we eliminate them, and the current power eliminate them, some madman may develop them in the future; we’ll need a defense against them if we’re going to eliminate them.”63 Reagan envisaged that the United States and the Soviet Union, and then the other nuclear powers, would negotiate reductions in – and ultimately the elimination of their nuclear arsenals. The United States would then “internationalize” the defense system by sharing it with other countries, including the USSR, and the shared defense would ensure the safety of a nuclear-free world.64

Reagan reaffirmed that “if defensive systems could be found, they would be available to all. This would end the nuclear nightmare for the U.S. people, the Soviet people, all people.” He underscored that “the U.S. would be prepared to reduce nuclear weapons to zero and ultimately to eliminate them.”65 Despite their clashes over SDI, Reagan and Gorbachev agreed on the idea of 50 per cent reduction in strategic arms, and both called for early progress on an interim INF agreement. Shultz thought that “we might succeed in breaking INF out for special treatment.”66 Moreover, the U.S.-Soviet communique entailed a crucial statement from Ronald Reagan’s 1984 State of the Union speech: “The sides […] have agreed that a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought. Recognizing that any conflict between the USSR and the U.S. could have catastrophic consequences, they emphasized the importance of preventing any war between them, whether nuclear or conventional. They will not seek to achieve military superiority.”67 The Geneva summit was a game changer. It proved that Reagan and Gorbachev could do business with each other. It offered a way forward and catalyzed further intense arms control debate.68 The momentum on arms control was there to stay.

In January 1986, Mikhail Gorbachev presented a radical plan to abolish nuclear weapons by the year 2000. His program envisioned three stages. The first stage foresaw a 50-percent reduction of strategic nuclear weapons over 5 to 8 years and an agreement to eliminate all medium-range nuclear weapons in Europe. Starting in 1990, the second stage entailed the participation of Britain, France and China. They would join the process by freezing their arsenals, and all nuclear powers would eliminate their tactical weapons and ban nuclear testing. Starting in 1995, the third stage envisaged the liquidation of the remaining nuclear weapons. On 14 January 1986, Gorbachev presented the program in a letter to Ronald Reagan before he made a public announcement the following day.69 Reagan was thunder-struck: Gorbachev attempted to seize the propaganda initiative by hijacking his vision of a nuclear-free world, but Reagan welcomed the initiative. “It has a couple of zingers in there which we’ll have to work around,” Reagan wrote in his diary. “But at the very least it is a h-1 of a propaganda move. We’d be hard put to explain how we could turn it down.”70 Reagan did not want to turn it down. “I want our children and grandchildren particularly to be free of these terrible weapons, he told one of his generals.”71 George Shultz thought the same way. He thought that “we should see this as an opportunity to transform Gorbachev’s concept so that it matches your own vision for a non-nuclear world. […] Our response should elaborate on our own concept for a process leading to the elimination of nuclear arms, concentrating on the bilateral reductions necessary in the first stage of that process.”72

NATO had to find a proactive response as well. NATO’s reaction had to balance interest in arms control and emphasis on the continued relevance of nuclear deterrence. The Reagan-Gorbachev arms control diplomacy annoyed French and British policymakers. French Foreign Minister Roland Dumas and President Mitterrand’s chief foreign policy adviser Hubert Vedrine criticized Reagan’s idea for a nuclear-free world. They argued that Reagan’s vision for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons “had boomeranged” with Gorbachev’s proposal of 15 January.73 Gorbachev made bold proposals in public whereas his INF negotiations in Geneva still showed no signs of movement. The Soviet approach still involved compensation for British and French nuclear forces. French policymakers stressed the need for arms control to include both conventional as well as nuclear weapons. In January 1986, Dumas emphasized the need to address the enormous conventional imbalance in Europe.74 German policymakers were concerned as well. Germany’s Defense Minister Manfred Woerner was skeptical. He preferred an interim solution instead of a zero-zero outcome on INF: In February 1986, he told his British colleague Andrew Younger privately that “he saw the attraction of an INF agreement which preserved some Western deployments.”75

Reagan acknowledged the need for in-depth consultations in NATO. In February 1986, he sent Ambassadors Paul Nitze and Edward Rowny to Europe and Asia for consultation with key U.S. allies. Nitze consulted with senior government leadership in London, Paris, Bonn, Rome, The Hague and Brussels. He also held consultations with the North Atlantic Council.76 Nitze brought back negative views from Europe arguing that a favorable US response to Gorbachev’s program might be too costly in terms of NATO solidarity. Nitze noted that “some opponents of zero-zero INF in Europe argued that withdrawing U.S. INF forces could decouple the U.S. from Europe, a situation which they claim the 1979 dual-track decision was aimed to redress.”77 One of the zingers in Gorbachev’s January 1986 proposal was that it advocated zero-zero on INF in Europe whereas it put no constraints for the Soviet Union’s mobile SS-20s in Asia. Ronald Reagan thought about countering this stipulating a 50 per cent cut in those SS-20s, plus a Soviet commitment to further reductions in the next stage. British policymakers were not convinced though. In February 1986, Margaret Thatcher told Paul Nitze that “a zero-zero solution [in Europe] would call into question the NATO decision to deploy Pershing II and Cruise missiles as an essential part of the Alliance’s spectrum of nuclear deterrents. In any case, our preferred solution was zero-zero on a global basis.”78 Reagan’s next step was to send out letters to key allies in order to foreshadow his proposed response to Gorbachev: “By noting apparent Soviet agreement to our objective of substantial nuclear reductions and by elaborating our own steps forward for achieving that end,” Reagan wrote the other heads of NATO countries, “we can challenge the Soviet leadership to see whether their proposal advances the process of achieving substantial mutual reductions and limits which are equitable, verifiable, and stabilizing.”79 But this process could only move forward with unrestricted U.S. research into SDI, Reagan insisted.

Gorbachev’s nuclear abolition plan caused a major policy debate in Washington DC. The Pentagon saw it as a disaster and a Soviet propaganda ploy aimed at killing SDI.80 George Shultz stepped forward arguing that Gorbachev’s initiative matched Reagan’s own thinking. On 17 January 1986, Shultz gave a speech to the State Department’s arms control group: “We need to work on what a world without nuclear weapons would mean to us and what additional steps would have to accompany such a dramatic change. The president has wanted all along to get rid of nuclear weapons. The British, French, Dutch, Belgians, and all of you in the Washington arms control community are trying to talk him out of it. The idea can potentially be a plus for us: The Soviet Union is a superpower only because it is a nuclear and ballistic missile superpower.”81

Meanwhile, Reagan and Gorbachev needed time and energy for a comprehensive review of their arms control policies. The process of adaption continued throughout spring and summer 1986. Ronald Reagan was still committed to his vision of a world without nuclear weapons. Shultz’s advice was to seek constructive moves on INF and START while meeting Gorbachev’s concerns on ABM and SDI. Shultz thought that “our proposal would not be an open-ended commitment that would delegitimize nuclear weapons. Rather, it envisions a continued role for an effective deterrent until the conditions exist where we could contemplate the elimination of nuclear weapons.”82

However, public opinion and the Reagan’s White House advisers were not ready for bold moves. Gorbachev was frustrated about Reagan’s response. In the spring of 1986, Eduard Shevardnadze was not willing to see George Shultz for further arms control discussions. Shevardnadze told U.S. Ambassador Arthur Hartman that “the Soviet Union favored dialogue but that circumstances were not yet right for a meeting between himself and Shultz.”83

George Shultz grew alarmed. Time was running away. Reagan envisaged 1986 as the year for negotiations on key arms control elements permitting the conclusion of new arms control agreements by 1987 and their ratification by 1988. When Reagan made this point in a conversation with Anatoly Dobrynin in April 1986, the latter insisted on careful preparation: “We need to know what minimum will be achieved,” Dobrynin said. “We cannot risk failure at the top level.” It was essential to have something that both sides could announce at the next Reagan-Gorbachev meeting. It seemed like an INF agreement was in reach. “We agree that we should go down to zero. We do disagree on how to apply this globally. But we could bridge that at the next summit,” Reagan argued.84 Gorbachev thought the same way: He recalibrated his negotiation position. In a September 1986 letter to Reagan, he reiterated that an INF agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union would not count British and French nuclear forces. Moreover, Gorbachev considered on-site inspections and conveyed his readiness to cut the Soviet Union’s land-based missiles. He still planned to travel to the United States in 1987, but why not meet sooner? His suggestion was to see Reagan in Europe.85

Reagan agreed to host a summit in 1986: The meeting was scheduled to begin on 11 October 1986, in Reykjavik, with little time to prepare. Prior to the summit, George Shultz did not expect major breakthroughs over the short-term. Shultz’s aim was mainly to prepare the ground for a future U.S.-Soviet summit in the United States. Shultz argued that “arms control will be key not because that is what the Soviets want, but because we have brought them to the point where they are largely talking from our script. This does not mean we will find Gorbachev easy to handle in Reykjavik, but it means we are justified in aspiring to accomplish something useful there,86 Shultz thought.

Gorbachev came to Reykjavik trying to achieve a compromise on SDI. He wanted to achieve an SDI test moratorium. Reagan rejected this proposal. Gorbachev was frustrated. How could he trust Reagan to share SDI with the Soviets when America was not even willing to share harvesting and oil-drilling technology? There was no way to break the impasse. Reagan and Gorbachev were united in their desire to achieve a world without nuclear weapons, but they failed to find a common path to move forward. “With respect to SDI,” Reagan said, “he had made a pledge to the American people that SDI would contribute to disarmament and peace, and not be an offensive weapon. He could not retreat from that pledge.”87 Gorbachev noted that the meeting “had not been in vain. But it had not produced the result that had been expected in the Soviet Union, and that Gorbachev personally expected. Probably the same could be said for the United States,” he observed.88 At the same time, Reykjavik brought progress in terms of INF: Apparently, the Soviets were ready for an INF treaty and prepared for a comprehensive verification regime. In Reykjavik, Reagan and Gorbachev reached preliminary agreement to eliminate all Intermediate Nuclear Forces in Europe: Moreover, Gorbachev agreed to reduce Soviet SS–20s in Asia to 100 total warheads in return for the elimination of all US Pershing II and Ground-Launched-Cruise Missile warheads except for 100 warheads in the United States.89

During their last session in Reykjavik, Reagan and Gorbachev came unexpectedly close to the potential elimination of all nuclear weapons within a ten-year period. Reagan asked “whether Gorbachev was saying that beginning in the first five-year period we would be reducing all nuclear weapons – cruise missiles, battlefield weapons, sub-launched and the like. It would be fine with him if we eliminated all nuclear weapons,” Reagan argued. “We can do that. We can eliminate them,” Gorbachev responded. “Let’s do it,”90 said Shultz. However, SDI stood in the way. “He would not destroy the possibility of proceeding with SDI,” Reagan emphasized. The meeting adjourned with no agreement. But it was important for future summits that both leaders discovered the extent of the concessions the other side was willing to make.

The NATO allies had mixed feelings about Reykjavik. On the one hand, they endorsed Reagan’s proactive diplomacy and his engagement with Gorbachev. On the other hand, they were concerned about Reykjavik’s implications for NATO’s defense policy: Margaret Thatcher was upset: “The elimination of all nuclear weapons would strike at the heart of our deterrence strategy. The Soviets clearly have conventional superiority. Doing away with nuclear weapons would leave the Soviets with the upper hand,” she told Ronald Reagan in a telephone conversation on 13 October 1986.91 Thatcher believed Reagan’s nuclear diplomacy could potentially undermine NATO’s security leaving Europe without adequate defenses.92 German policymakers feared that Reagan’s and Gorbachev’s global 100-INF ceiling could destroy support for NATO’s zero-zero approach. German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher insisted that NATO had to stick to its zero-zero objective. At NATO’s Foreign Ministers meeting in December 1986, he pointed out that “the Alliance must not speak with two tongues on the zero-zero solution for LRTNF in Europe. It had been in the logic of the two-track decision from the outset. The importance of adhering to this position went beyond the question of defence capability: It affected the motivation of the uniformed soldier and the support of the public for our defence effort.”93

Reykjavik had bold implications. The prospective conclusion of an INF agreement and deep reductions of strategic nuclear weapons would bring conventional arms control and the imbalances in short-range nuclear forces to the front burner of NATO’s arms control agenda. Both issues necessitated in-depth allied consultations. NATO needed time to adapt and to reel in Gorbachev’s arms control proposal in its own agenda. In October 1986, Helmut Kohl’s foreign policy adviser Horst Teltschik thought that “perhaps it was just as well that the meeting in Reykjavik had broken up when it did. […] A far-reaching agreement in Reykjavik would have been very welcome just now in Bonn, but from the professional point of view a pause for reflection was no bad thing.”94 Despite its failure, George Shultz saw the Reykjavik summit as a conceptual success. In November 1986, he turned to President Reagan writing that “in a series of steps culminating in Reykjavik, the Soviets have accepted our conceptual framework for arms control: substantial, verifiable reductions in offensive forces to low, equal levels. […] The results of Reykjavik will be difficult to translate into concrete agreements, but […] the results are irreversible in political terms.”95 Shultz saw it as an encouraging sign that the Soviets were not withdrawing from the nuclear bargaining table like in 1983. “This time they are playing smarter,” Shultz noted. “This could mean that the Soviets will reengage very quickly, enabling us to resume serious discussions without much loss of momentum.”96

George Shultz’s forecast was correct. In 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev stepped forward with even more comprehensive INF arms control proposals: In February, he suggested the inclusion of missiles of shorter ranges between 500 and 1,000 km including the West German Pershing IA and the Soviet SS-23 and SS-12. Moreover, Gorbachev announced his decision that he would no longer link an INF Treaty to other arms negotiations on offensive strategic weapons and the SDI/ABM systems.97 Thus, he untied the Reykjavik package. In addition, Gorbachev conveyed his willingness to reduce and eliminate shorter-range missiles as part of his vision of a non-nuclear world. In practice, this would mean a non-nuclear Europe except British and French deterrents, with the balance of conventional forces heavily in the Soviet Union’s favor. What was the best way for NATO to respond? Should NATO take Gorbachev at his word, as Hans-Dietrich Genscher suggested in an important address in February 1987?98 Or should NATO respond in a cautious way along the lines that Margaret Thatcher proposed when she told Mikhail Gorbachev that “you take grave actions irresponsibly […] We could not imagine that you’d send troops to Czechoslovakia, but you did. The same again with Afghanistan. We are afraid of you.”99

Ronald Reagan was determined to accelerate the INF negotiating process: On 4 March 1987, the U.S. arms control negotiators in Geneva introduced a draft INF agreement. Ronald Reagan hailed Gorbachev’s decisions of February 1987 at a press conference on 3 March 1987: “This removes a serious obstacle to progress toward INF reductions […] I want to congratulate our allies for their firmness on this issue. Obviously, our strength of purpose has led to progress,” Reagan said.100 In turn, Gorbachev invited Shultz for negotiations in Moscow in order to facilitate the completion of an INF treaty before the end of 1987. Reagan sent out Shultz despite seventy US Senators and Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger expressed the view that he should stay home.101 The skeptics used the notion of linkage in U.S.-Soviet relations as an argument against Shultz’s visit. They saw Soviet penetrations of the US embassy in Moscow as an argument to close it down. Caspar Weinberger and the Head of the National Security Agency William Odom argued it was impossible for Shultz to have secure communications during his visit to the Soviet Union.102 Shultz crushed his critics aside: If “we still had had the same notion of linkage as in the past,” he later recalled, “everything really would have just shut down.”103

Shultz arrived in Moscow on 13 April 1987 and met with Gorbachev the following day. Gorbachev emphasized his readiness to include the shorter-range SS-23 missile in an INF agreement: He addressed NATO’s concern that shorter-range INF missiles with a range between 500 and 1,000 kilometers could be used to circumvent the effects of an INF agreement. Negotiators and administrative officials referred to this tandem of short-range and long-range INF as the “global double zero” proposal. Gorbachev anticipated that Shultz did not have a mandate from NATO for negotiations over the global double zero. “There was no problem from the Soviet side,” he said. “In fact,” he continued, “all the problems were on the other side. You in NATO were like a cat walking around a bowl of hot porridge (kasha).”104

Indeed, Shultz reserved the right to take another look and to consult in NATO. He insisted on the principle of equality: The United States needed the right to match, whether the U.S. exercised it or not. Gorbachev understood Shultz’s concern. Moreover, both were in agreement about the need of a comprehensive verification regime that was envisaged as a role model for further arms control treaties on strategies weapons. Shultz’s meeting with Gorbachev brought the breakthrough that both sides had been seeking. Finally, Gorbachev used the meeting in order to reiterate that “we should discard the old stereotypes, the old approaches, and try to interact.” Shultz agreed: “There were very powerful forces at work that had nothing to do with capitalism or socialism, but affected both. They were changing the world, and this deserved discussion.”105 The European allies generally welcomed the double-zero idea. But the proposal triggered concerns that the global double-zero could bring NATO in a situation in which it would rely more heavily on its conventional forces as part of its deterrent.

Another concern arose over the impact on short-range nuclear forces (SNF): The prospect emerged that the only weapons left in Europe might be stationed in and targeted at East and West Germany. “The shorter the missile, the deader the German,” quipped Volker Ruehe, the CDU’s deputy floor leader in the Bundestag and its defense spokesman.106 The easiest solution would have been a third zero on SNF. That was not in sight though. NATO had to highlight the distinction between the removal of INFs and the need to maintain its nuclear capability. The time was not right to abolish nuclear weapons: NATO needed them for deterrence in order to balance the Soviet Union’s conventional military strength. The global double-zero brought the Kohl government into a paradoxical situation. The Schmidt and Kohl administrations had long championed NATO’s arms control track, but the global zero solution threatened to bring the Federal Republic into the kind of singularized position that German policymakers were determined to avoid.

Helmut Kohl supported the zero-zero solution on long-range INF weapons. The outstanding question was whether his government would approve the second zero on short range INF with a range between 500 and 1000 kilometers. In April 1987, it seemed that Kohl was inclined to accept it on the understanding that the German Pershing 1a missile was not affected.107 The Pershing Ia was a field artillery missile with a range of about 750 kilometers that was deployed with three U.S. battalions in Europe and two German Air Force wings, the control of the nuclear warheads remained in the hands of the U.S. Army. NATO had already decided to phase out the 72 Pershing Ia deployed in Germany by 1991. Back in the early 1980s, the Schmidt government had decided to modernize the Pershing missiles: Pershing Ia would be turned into Pershing Ib with a range of a little below 1000km. The Pershing Ib would cause major verification problems: It had the potential to undermine an INF agreement as it could be turned into a 1800km Pershing II missile within 48 hours.

In April 1987, Eduard Shevardnadze and Mikhail Gorbachev raised the Pershing issue in their discussions with George Shultz: “The Soviet side could not agree that the weapons of one side would be eliminated while the other would just make rearrangements of its military presence on the European continent. […] That path had no end; there would be no agreement, no reductions.”108 The Kohl coalition government debated the issue intensely. The Free Democrats and Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher were ready to accept global double-zero whereas the majority within the conservative parties were determined to seek the exclusion of Pershing Ib from an INF agreement. On 27 April 1987, the Kohl government declared that it would postpone a final decision: Kohl’s coalition was divided, and there was no easy way out.109 Moreover, Gorbachev’s global double zero proposal triggered intense discussion in NATO. The alliance was in the search for consensus on the appropriate response: The NATO High-Level Group (HLG) debated the issue during its meeting in Albuquerque from 22–24 April, yet it did not reach final conclusions. It was pointed out that “there appears to be a strong politico/military case for preserving the option to deploy P1B. But to reject the Soviet offer on these grounds would only make sense if there were some realistic prospect of NATO at some point actually taking up that option. How realistic was this? And on what conditions might they be deployed?”110

NATO’s debate over the global double zero was on. What could be the solution? At this juncture, NATO sought an analysis of what it needed for its security in the aftermath of the INF Treaty, and it then had to relate its arms control priorities to that. From a German vantage point, the key point was not to become a special nuclear zone. The bottom line for the Kohl government was NATO’s acknowledgement that the number of short-range nuclear forces with a range of up to 500km could not stay unconstrained indefinitely. A potential solution for NATO was to link acceptance to the global double zero solution with the announcement of a new NATO study of modernization requirements and negotiation options for SNF and of their relationship between such systems and the conventional and chemical imbalance. In May 1987, Helmut Kohl told Margaret Thatcher that “if there was a zero above 500km, Germany would be uniquely exposed and vulnerable to these short-range systems. […] There was a connection between the solution found above 500km and provisions made for systems in the range 0-500km. The latter could not be excluded from negotiations altogether. There must be some indication of readiness to deal with them, in connection with what happened in negotiations on chemical and conventional weapons.” Thatcher’s response was blunt: “Europe was dependent on these short-range systems as part of its response to Soviet superiority in chemical and conventional forces. They were a vital part of the strategy of flexible response. This was why the United Kingdom insisted upon setting a floor on further negotiations at 500km, until Soviet chemical weapons were eliminated and the imbalance in conventional forces was removed.”111 Eventually, NATO postponed the decision over SNF modernization.112 NATO’s internal debate did not stand in the way of the INF Treaty.

On 15 June 1987, Ronald Reagan delivered a TV address from the Oval Office and announced that the United States would formally propose the global double zero solution to the Soviet Union.113. Finally, Gorbachev’s adoption of the global double zero and NATO’s arms control consensus paved the way for the conclusion of the INF Treaty. George Shultz was right when he pointed out that “there are more than two players in the East-West game. NATO governments face tough political choices on next steps in nuclear and conventional arms control and modernization. Where they come out will bear great influence on our dialogue with the Soviets, and could define the direction of the Alliance for the remainder of the century.”114

In the summer of 1987, the rapid conclusion of an INF agreement and another U.S.-Soviet summit were in the making. At the same time, there were still obstacles to the conclusion of an INT Treaty. There was still no satisfactory resolution of the German Pershing 1A problem. The question of verification was still another outstanding issue. Finally, on 26 August 1987, Helmut Kohl announced that he was ready to renounce modernization of Pershing 1A and indeed do way with the missiles.115 In September 1987, the Reagan administration tabled new proposals for verification: They envisaged a short transitional period for the elimination of the missiles – one year for short-range INFs and three years for long-range INFs; and a ban on modernization, production and flight testing of all the systems involved. Verification during the transitional period would be ensured by provisions for initial detailed exchanges of data and baseline inspections to verify this data; on-site inspection of the destruction and dismantlement of the missiles and a quota of on-site inspections of declared sites. In addition, there would be a provision for short notice inspections of certain categories of “suspect” sites – that is ICBM-related facilities.116

George Shultz and Eduard Shevardnadze discussed these issues during their talks in Washington in September 1987. Shultz pointed out that “if we succeeded in reaching an INF agreement, it would have the strongest verification in the history of arms control by a long shot.”117 NATO discussed the implications of the incipient INF treaty on the occasion of a Nuclear Planning Group Meeting in Monterey, California, on 3 and 4 November 1987. Secretary General Peter Carrington said that “the INF agreement represented an enormous achievement for the alliance and would make an important contribution towards the maintenance of public support for nuclear deterrence. At the same time there were cross currents which would require careful handling: Euphoria at the agreement and calls for further nuclear reductions on the one hand, pressure for ‘compensating’ new weapons deployments on the other.”118

Finally, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed the INF Treaty on 8 December 1987 on the occasion of their Washington summit meeting. It was a historical occasion. Reagan took the microphone when he entered the stage: “It was over 6 years ago, November 18, 1981, that I first proposed what would come to be called the zero option. It was a simple proposal one might say, disarmingly simple. Unlike treaties in the past, it didn’t simply codify the status quo or a new arms buildup; it didn’t simply talk of controlling an arms race. For the first time in history, the language of ‘arms control’ was replaced by ‘arms reductions’ – in this case, the complete elimination of an entire class of U.S. and Soviet nuclear missiles.” Reagan continued quoting the old Russian maxim “Doveryai, no proveryai – trust, but verify.” Gorbachev interjected with a smile: “You repeat that at every meeting.”119 The summit meeting reflected the friendly relationship between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. The INF Treaty was a landmark agreement: It banned all of the two nations’ land-based ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and missile launchers with ranges of 500–5,500 km. By May 1991, the United States and the Soviet Union had eliminated 2,692 missiles, followed by 10 years of on-site verification inspections.120

The Washington Summit was a cutting-edge event: The INF Treaty marked the end of the Euromissile problem. In addition, it was a catalyst for the START negotiations, the talks on short-range nuclear weapons and the East-West negotiations on conventional weapons armaments. The INF Treaty facilitated the peaceful end of the Cold War – it was the cornerstone of Euro-Atlantic security in a time awash of bold changes and promised to bring a more peaceful and more cooperative world. At NATO’s December 1987 Foreign Ministers’ Meeting, George Shultz stressed the need for NATO to seize the opportunities of Gorbachev’s glasnost and perestroika: “It was important, without neglecting the lessons of the past, to look to the future,” Shultz said: “The world would be very different in 5 to 10 years. Openness to ideas, information and contacts were key. […] Something different is going on, the change in the relationship with the Soviet Union was profound. This did not mean that the Russians were going to roll over and be nice to us. Allied strength and cohesion would remain vital. But the prospects for a major breakthrough were there.”121