- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

- Campaigns & Elections

- State & Local

- California

For reasons either justifiable (my job necessitates keeping track of what politicians are up to) or masochistic (the urge to be a glutton for punishment), I make it a habit to sign up for officeholders’ and candidates’ email solicitations.

Well, that and intellectual curiosity: as a recovering speechwriter, I naturally gravitate to political messaging—even when it’s politicos spamming me with pleas for money.

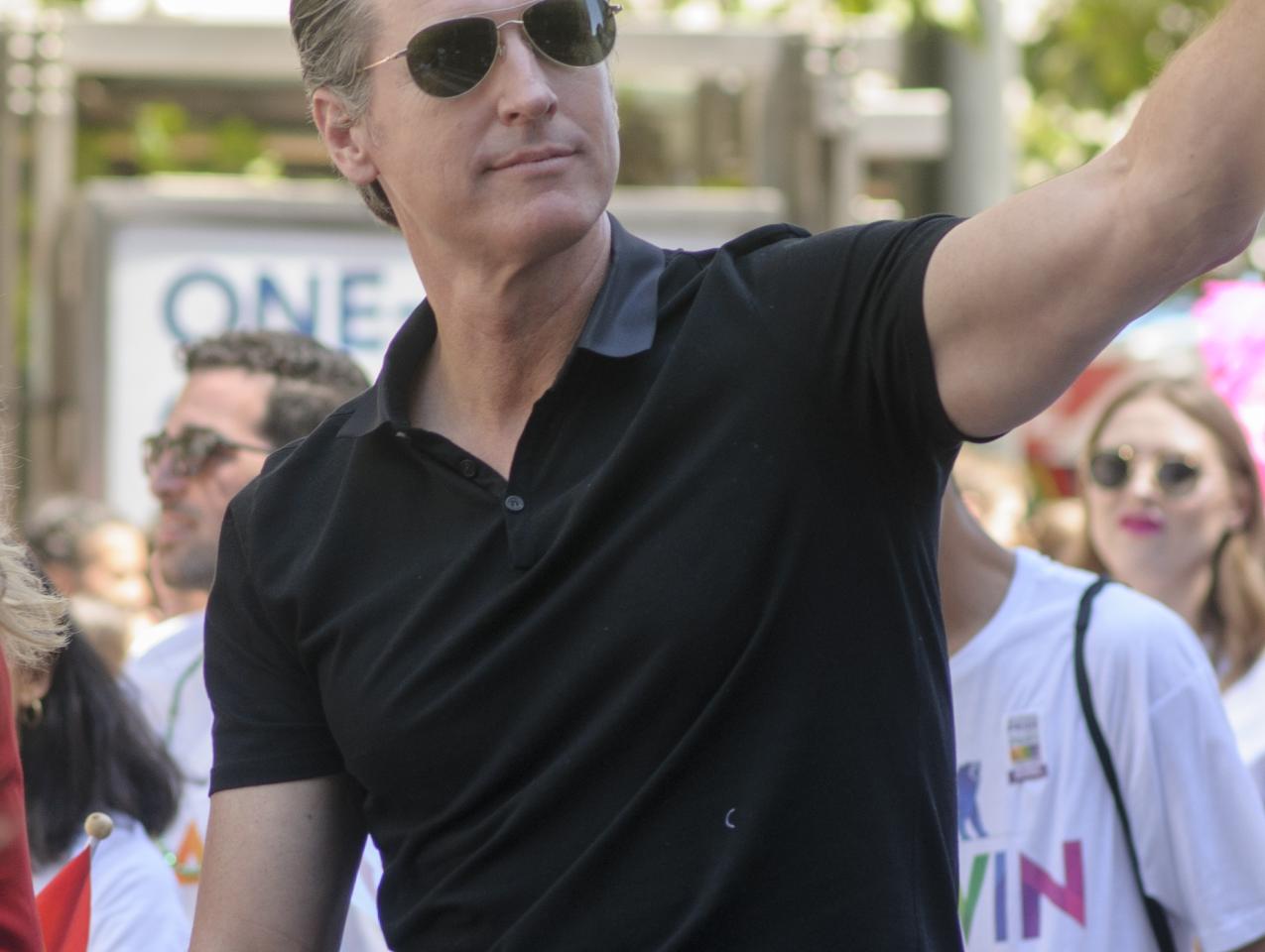

Lately, it’s California governor Gavin Newsom’s campaign email traffic (he’s the subject of a recall election presumably later this year) that has my attention—both for its frequency (as California’s second-quarter deadline for reporting campaign cash arrived this week, Newsom’s campaign was in high gear, sending multiple emails daily) and for the “ask” (a request for a measly $3, which suggests the governor’s anti-recall campaign has more interest in collecting the email addresses of would-be voters than actual dollars).

Credit Newsom’s campaign with consistency, as all emails have the same two words: “Republican recall.”

That said, sometimes the drama is little over the top—for example, last weekend’s plea: “What if Caitlyn Jenner or some far-right Republican takes office as we’re coming back and COVID and the effects of climate change are ravaging California?”

Other times, the emails should come with a laugh track—a case in point being this late June email: “$75,000. That’s what Mike Huckabee JUST contributed to the campaign to recall Gavin Newsom.” Seriously, folks, what is the number of Californians who could spot Huckabee, a former Arkansas governor and GOP presidential candidate, in a police lineup much less be frightened by the mention of his name?

Oddly enough, money should be the least of Newsom’s concerns in the upcoming recall vote. That’s because California’s campaign laws favor the incumbent in such special elections. Whereas Newsom’s recall rivals have to comply with the state’s donation limits, Newsom doesn’t. The result: eye-popping checks sent the governor’s way from some prominent Californians: $3 million from Netflix CEO Reed Hastings; $200,000 from Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Apple legend Steve Jobs (OK, maybe her donation’s isn’t so “eye-popping” as she’s worth an estimated $21 billion).

If you’re concerned about California’s future, I suggest you pay less attention to the likes of Mrs. Jobs and more to what the Newsom campaign is collecting from special interests, as it raises the question of what donors might want in return.

That begins with the aforementioned Mr. Hastings.

In 2018, he donated $7 million to the gubernatorial effort of former Los Angeles mayor Antonio Villaraigosa (a loophole in California’s campaign finance rules allows unlimited sums to go “independent expenditures” [IEs] that support a candidate without coordinating with the candidate’s campaign).

Hastings’s motivation in the summer of 2018? He and a band of fellow deep-pocketed charter-school advocates wanted a governor not under the thumb of teachers’ unions (Villaraigosa, who started his political career as a union organizer, once blasted his city’s teachers union as “the largest obstacle to creating quality schools”).

Hastings’s motivation in the spring and summer of 2021? The guess here: it still has to do with teachers’ unions, Hastings perhaps wagering that a $3 million tithe to Newsom improves his standing with a governor also backed by the all-powerful California Teachers Union (always thinking strategically, CTA endorsed Newsom in early June—not coincidentally, as the governor and the state legislature began the debate over how to spend California’s budget windfall).

It shouldn’t be long before we have an actual date for the recall vote—if it’s to be in mid-September, that means Lt. Gov. Eleni Kounalakis will make the call in early to mid-July (Democrats want the election to happen sooner rather than later, even if it means tinkering with state law; Kounalakis can set a date as early as 60 days from the time of her announcement).

And as the summer progresses, look for two financial trends—the first being six- and seven-figure special-interest donations finding their way either to the governor’s war chest or to IEs.

In fact, the pattern’s already under way. A quick look at this donor tracker shows Newsom in possession of $1.5 million courtesy of the California Association of Realtors; $500,000 apiece from the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria and the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians; $400,000 from the United Nurses Association of California/Union of Health Care Professionals political action committee; $300,000 apiece from a pair of California labor unions; $295,000 from the Professional Engineers in California Government PAC; $250,000 apiece from two more labor unions (in this case, electrical workers); $200,000 from yet two more unions; plus an extra $200,000 kicked in by the Pechanga Band of Luiseno Indians.

Translation: assuming he survives the recall and then prepares for a re-election run in 2022, Newsom should anticipate a few queries from recall donors with regard to state contracts and gaming compacts (California’s gaming tribes might ask Newsom to put his muscle behind a 2022 ballot initiative allowing sports wagering at tribal casinos).

Money, by the way, makes for odd bedfellows in California politics. A deeper five into Newsom’s campaign finances shows a $32,000 donation by DoorDash—the same app-based delivery service that poured millions of dollars into 2020’s Proposition 22 and the gig economy’s pushback against a controversial labor law signed by Newsom.

The other financial consideration with regard to the recall: just how one-sided the money race may become.

Add up the special-interest donations listed a few paragraphs earlier and the sum amounts to just shy of $4.9 million (the number is only that modest because I limited the math to Newsom donations at $200,000 and up). By contrast, you won’t find an “organizational” donation of greater than $57,000 to the recall election candidacy of former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer, or one beyond $32,000 to John Cox, Newsom’s opponent in the 2018 general election.

One last financial takeaway from the recall: what a different campaign it might be if Caitlyn Jenner were on better terms with her famous clan.

When Jenner, the former Olympic athlete and Kardashian family patriarch, first jumped into the recall fray, the question was what impact her celebrity standing might have.

The answer so far: a disproportionate relationship between the media attention she receives—frequent appearances on national airwaves—and some woeful poll numbers.

But consider the ramifications if the Kardashians put a sliver of their considerable fortune behind Jenner’s campaign.

Last September, Forbes estimated the six women in the Kardashians’ reality orbit—“momager” Kris Jenner and her daughters Khloé, Kim, and Kourtney; and Caitlyn Jenner’s biological daughters, Kendall and Kylie—to be worth a collective $2 billion. And there’s the question of how much cash on hand the Kardashians might have. But imagine a world in which the Kardashians ponied up, say, $50 million in an “independent expenditure” benefiting Caitlyn Jenner.

But apparently that’s not meant to be. In late May, in yet another national television appearance (this time, CBS This Morning), Caitlyn Jenner offered the following: "You know, my family has certainly been out in the media and they've taken their shots, and they don't need to take any more. I said, ‘I am not going to ask you for one tweet. I'm not going to ask you for one thing. You guys go live your life. This is my deal. This is my decision to do this.’ I'm going to tell the media, ‘Stay away. Don’t ask them,’ and I told them just, ‘No comment.’”

So “no comment”—and let’s assume, no contributions.

Just one more reason why keeping up with Gavin Newsom, dollar for dollar, is a harsh reality for the governor’s recall opponents.