- Contemporary

- Law & Policy

- International Affairs

- History

Before I left for Afghanistan to help develop a new constitution in 2002, I gathered three books. The first was The Constitutions of Afghanistan. There have been seven constitutions since the first one in 1923, each representing an abrupt political shift. You don’t have to be a constitutional scholar to know that changing the constitution every decade is not a recipe for stability. These constitutions held lessons about past successes and failures, about important compromises and uncompromising extremism. None of these constitutions had been fully implemented, and I knew confidence in a new constitution would be hard-won.

The second book was The Federalist Papers, that brilliant compendium of essays about the nature and structure of government written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and other Founding Fathers. These essays—essentially op-ed pieces, written to promote popular support for the draft constitution of the United States—discuss the inherent factionalism of politics and how effective democratic institutions harness rather than succumb to the power of competition. They describe an interdependent web of institutions that balances competing interests. Afghanistan is nothing if not factious. Having witnessed four years of Afghanistan’s devastating civil war in the 1990s, I knew that eliminating competing interests was not possible—that’s what the last three decades of war and upheaval had been about. Instead, these interests would have to find a voice in the new political system and learn to coexist with other interests.

The third book was Joseph Ellis’s Founding Brothers, which describes the great debates that went on during the deliberations that led to the U.S. Constitution. The message of the book is one of great success, and great failure. The book describes a tense period during which the failure to create the Union seemed all too possible. There was tremendous animosity between some of these “brothers,” and issues such as slavery proved too divisive to tackle. In the end, compromise was achieved by addressing those issues that could be resolved, and setting aside those issues that could not. The great success, of course, was the creation of a federal system with a potent, but circumscribed, center and a series of checks and balances that would keep that center stable. The great failure was slavery, a grave evil that, left unresolved, nearly destroyed the Union.

Afghanistan in 2002 faced three weighty issues, each with the potential to undermine the creation of a stable, democratic state: regional versus national interests, power sharing at the national level, and the role of religion in the state. It was clear that without compromise on each of these issues, the prospects for consolidating the state remained dim.

For nearly two years I discussed, debated, and agonized over these issues with Afghans of all stripes. In December 2003, more than 500 Afghans gathered in Kabul to debate and ratify a new constitution. This constitutional convention, or Loya Jirga, approved the new constitution on January 4, 2004. The following are some of the debates that I saw emerge along the way.

Whose Taxes, Whose Budget?

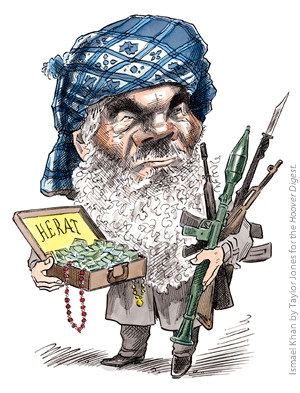

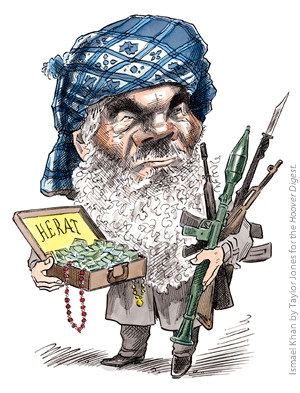

In 2002 I flew to Herat, the regional capital of western Afghanistan, which at the time was controlled by Ismael Khan, the “Warlord of the West.” Khan had led the mujahideen resistance against the Soviets in western Afghanistan in the 1980s, and from 1992 to 1995 he ruled a fiefdom in Herat during the civil war, until he was ousted by the Taliban. Khan quickly returned to power in Herat with U.S. assistance in 2001 after the fall of the Taliban.

In 2002 Herat was orderly and booming by Afghan standards. Trade from Iran and Turkmenistan was filling the coffers of Khan and the city’s merchants. Public works projects were bringing electricity and irrigation and creating roads and even parks. Motorists actually obeyed the neatly uniformed traffic police, and truckloads of armed Afghan militia careening through town—a fixture of other Afghan cities—were seldom seen.

I met with Khan in his hillside palace. Here was a man who collected an estimated $5–$10 million a month in customs revenue, which he refused to turn over to the central government, and maintained his own army, which was far larger than the new Afghan National Army being created in Kabul.

I expected Khan to argue strongly for regional power sharing, but he didn’t. Instead he argued for burden sharing. Khan railed against a corrupt central government that keeps—and which historically kept—everything for itself. He argued that he was spending the money he collected on Herat, where it belonged. Although other political and social figures in Herat may have lamented Khan’s authoritarian control, they supported his thesis that the central government took more than it gave to Herat.

The central government meanwhile argued that Herat was taking far more than its share and that although the revenues generated at the international border were collected in Herat, they belonged equally to all Afghans. Kabul didn’t have much money to send to Herat because the government simply doesn’t have many sources of revenue outside international assistance—over which it has very little control. Furthermore, Afghan law required Khan to turn over the revenues, and thus he was flouting the law.

Federalism?

Karim Khalili is a vice president (one of four) in the interim government and a leader of the Hazara minority group that occupies central Afghanistan. The Hazaras, Afghanistan’s third-largest ethnic group, are by far the poorest and most discriminated against of Afghanistan’s major groups. They are a double minority in Sunni Afghanistan, being adherents of Shia Islam with distinctive Mongolian features. Subjugated into the Afghan kingdom by force in the nineteenth century, the Hazaras have had a fairly rough ride since.

In the civil war of the 1990s, Afghanistan fragmented, and for the first time in a century the Hazaras had a degree of political autonomy, guaranteed by the force of arms. During this period, several Hazara figures began to argue for a federal arrangement in Afghanistan under which they would be guaranteed their basic rights, including freedom of religion. In the late 1990s, however, the Hazaras faced extreme persecution under the Taliban. I visited Vice President Khalili to see where he stood on the question of federalism, now that a constitutional process was at hand.

Khalili wanted to discuss minority rights, not federalism. Largely because of the divisiveness of the civil war period, Afghans are very wary of using the word federalism, fearing that it means ceding Afghanistan’s various regions to warlord control. Although no local leaders spoke openly about a desire for out-and-out independence, fragmentation had effectively created mini-states during the war, with different regions requiring separate visas and even printing their own currency. Thus most Afghans fear that a federal state means division and dysfunction and that power must first be concentrated in the center, draining the illegitimate power from the warlords, before legitimate power can devolve.

Khalili, like other regional leaders, was sensitive to these charges. His constituents were reluctant to cede political control to an unknown future central government, in that their historical experience with the centralized state had been largely negative. But the Hazaras have even less to gain from a divided Afghanistan. Their region is poor and isolated, and years of Taliban subjugation have left them feeling undefended. Thus Khalili reasoned that his region would benefit from a close relationship with the central government and that he would guarantee rights and resources for the region by fighting for high-level representation in Kabul. If that weren’t possible, he seemed to take some small comfort from the fact that the central government was weak and would likely remain so for years to come—unable to subjugate the regions to its authority.

Equity versus Effectiveness

Arriving at a gathering of Afghan human rights activists, I ducked into the low mud-brick building to find them already deep in debate. This group, which had come from various provinces for training in Kabul, had reserved the afternoon for a discussion of the constitution. Working on human rights in Afghanistan was neither particularly easy nor rewarding. These men and women—often working at great risk to themselves—are missionaries for human rights and democracy in hostile territory. They were both idealistic and pragmatic. They wanted to discuss the possible, but were fully capable of appreciating the probable.

The topic they spent the most time on that day was how power should be shared at the national level. Should Afghanistan have a parliamentary system, where the legislature would elect a prime minister accountable to the parliament? Or should they choose a presidential system, with a directly elected president and an executive branch independent of the legislature. A parliamentary system would more likely produce a coalition, ensuring that the executive would be controlled by a majority and that there would be broad ethnic representation. Coalitions, however, are often unstable, and a compromise leader may be chosen because of weakness instead of strength. A presidential system, by contrast, would produce a more unified executive, who should be able to act more effectively. But such a system could produce a president who represented only a fraction of the population. Afghanistan has had virtually no history with an independent legislature or judiciary, and previous Afghan presidents were autocrats.

The memories of the civil war were foremost in the minds of the activists. Political parties, required for a strong parliamentary system, are anathema to most Afghans. Political parties had never been legal in Afghan history, and most people associate them with the warring factions of the civil war. Most of the activists recognized that a parliamentary system, if it functioned well, would provide broader representation to Afghanistan’s many ethnic groups. However, the possibility of serious division in the parliament and warlord interference in the elections weighed heavily on their minds. Even though the country had suffered through unrepresentative and despotic presidents, the civil war made a weak center seem more threatening than a strong one. Ultimately, however, most of the activists concluded that the best way to guarantee rights in Afghanistan’s immediate future would be to have a strong center. With Hamid Karzai at the helm and the international community involved, they felt that a central government had a better chance of protecting citizens and promoting democracy than the warlord-controlled regions. In the long term, a more broadly representative system would probably be better for a polyethnic country like Afghanistan. But, under the current circumstances, one effective leader who could bring the country together was a better gamble.

The Role of Islam

The word for constitution in Dari (Afghan Persian) is kanoon-asasi (fundamental law). For many Muslims not familiar with the purposes of a constitution, this meaning sounds like an affront to Islam. At delegate elections for the Loya Jirga, one representative stood up and decried the whole undertaking: “What is this about another fundamental law? The Koran is the fundamental law. Let those who have things to say against the Koran come forward.”

The role of Islam in the state and laws of Afghanistan has a complex history. In the 1880s, when the state first began to consolidate, Islamic law was the law of Afghanistan. Judges were essentially clerics who ruled using their interpretation of religious law rather than any official source. Then, as the state grew, two legal systems and two court systems were created: one for religious law and one for state law. Gradual reforms from the 1930s to the 1960s led to a sea change in the 1964 constitution in which the legal systems of the country were united. Laws were now to be passed exclusively by a legislative process. Islam would serve as a basis for laws and laws could not be contrary to the principles of Islam, but Afghan law was no longer “Islamic law” but state law with Islamic origins. This delicate balance was in line with gradualist democratic transformations in other Islamic societies.

But this experiment with democratic modernization in Afghanistan collapsed in the 1970s after a series of coups set off a war between elite urban Communists (eventually backed by the Soviet military) and Islamists who drew support from a traditional and highly conservative rural population (and foreign anti-communist, anti-Soviet funding). The earlier political and legal compromise was decimated by extremist elements on both sides. The Taliban, in consolidating its ultra-fundamentalist regime from the chaos of post-Soviet Afghanistan, ratcheted the Islamic bar so high that, by 2002, even the chief justice of the Supreme Court was arguing that the Koran was the constitution of Afghanistan.

Thus the debate about the role of Islam and government in 2003 was more conservative than it had been in 1964. One day, while working to draft a law that would determine the structure and function of the judiciary, I got into an argument with an Afghan colleague of mine who insisted that all judges in Afghanistan must be Muslim because the president would be Muslim and that the power of judges flows from the head of state according to Islamic jurisprudence. Although disturbed that non-Muslims couldn’t be judges (99 percent of Afghans are Muslim, making the issue unlikely to surface), I was more concerned that judicial independence from the executive couldn’t exist under his view of Islam.

Judicial independence is a bedrock principle of the separation of powers critical to democratic consolidation, one that I hoped would be strengthened, rather than weakened, under the constitution.

But judicial independence without judicial responsibility or accountability can be equally dangerous. In the lead-up to the constitutional convention, the fundamentalist cleric at the head of the Supreme Court and his backers were pushing changes that would make the judiciary very powerful. They wanted the Supreme Court to have the power of judicial review—the ability to declare laws or government acts unconstitutional. This power is a regular feature of modern democracies, but with the prominent role of Islam in the constitution, it comes with a twist. Because the constitution would likely say that no law could be contrary to Islam, the court would have the power to declare laws unconstitutional on the basis that they were un-Islamic. The Supreme Court would thus become a clerical body imbued with religious authority.

Epilogue

My small library served me well in interpreting the constitutional convention and its outcome. The enduring message of each book is that context and compromise matter far more than empirical notions of right and wrong. A constitution itself says nothing unless it is truly a distillation of shared values and elite political compromise.

The delegates to the constitutional convention were deeply engaged in these timeless debates. A friend of mine, a liberal lawyer and publisher from western Afghanistan, sat arguing through the night about law and Islam with his turbaned bunk mate, a religious conservative from eastern Afghanistan. But these crucial debates did not receive their due on the convention floor. The short-term interests of key players prevented a serious examination of the historical implications of their decisions. Backroom dealing short-circuited the process of meaningful compromise as the interim government and its international backers tried to ram through a sloppy, last-minute draft constitution. On the convention floor the mujahideen and religious conservatives hijacked the debate through intimidation. The chairman of the convention took to calling opponents infidels, and a bloc of more than 200 frustrated ethnic minorities briefly boycotted the convention.

So how did each of our stories play out?

Ismael Khan, the Warlord of the West, was the biggest loser in both structural and practical terms. Provincial authorities were given no local control over budgetary or political matters. On paper, the central government holds all the cards, appointing provincial governors, controlling the budgets, and maintaining the national army and national police force. This wishful thinking ignores the reality on the ground; power is disbursed throughout the country, protected by interests, grievances, and the force of arms. There is only the most general language about distributing national wealth among the regions. In the end, regional leaders were given very little to allay their fears about future domination by an unrepresentative central government. Khan, the most potent symbol of resistance to central government authority, fared even worse. In September 2004, one month before the first presidential elections, he was removed from power by the Afghan government (with U.S. military backing) during a crisis with a regional rival.

Vice President Khalili, the Hazara leader who took a middling path, got middling results. Power sharing within the national government was concentrated in a U.S.-style presidential system—handcrafted for President Karzai. Although there are protections for minorities in the constitution, such as recognition of language and ethnic diversity, and the Hazaras received a new province, gerrymandered for their benefit, the central government has neither the capacity to enforce rights nor the balance of powers to restrain the discriminatory abuse of power. The personal outcome for Khalili was also mixed. He was one of Hamid Karzai’s running mates in the first presidential elections in 2004 and is now vice president of Afghanistan. However, another Hazara leader, Mohammad Mohaqeq, ran against Karzai and won most of the Hazara vote, pointing to the desire of Afghanistan’s ethnic minorities to be both included and autonomous.

The religious fundamentalists may have come out the strongest, winning three critical battles. First, the language in the constitution that requires Afghan law to be in accord with Islam was strengthened. In the 1964 constitution, laws could not contradict the “basic principles” of Islam. In the new constitution, Article 3 states that laws cannot contradict the “tenets and provisions” of Islam, a formulation suggesting a much stricter adherence to Islam. Their second victory is the broad authority given to the Supreme Court to review laws and treaties for their compliance with the constitution. When this power is combined with Article 3, the Supreme Court has the power to reject laws and treaties on the basis that they are un-Islamic.

With the wrong court, these powers could become a dangerous weapon in the hands of extremists intent on using Islam as a bludgeon to control Afghanistan’s political development. Sadly, that court is already in place. The chief justice is the former head of a madrassa (religious school) in Pakistan—the type of institution from whence the Taliban sprang. He has set up a fatwa (religious edict) council at the High Court, which the deputy chief justice told me was illegal. And the head of the Supreme Court office for public information is a former Taliban official.

Just 10 days after the passage of the new constitution, contrary to that constitution and without any case before it, the Court declared that the broadcast of female singers on TV was un-Islamic and therefore illegal. The chief justice has taken similar stances against coeducation and cable TV; in 2004 he tried to have a presidential candidate disqualified and prosecuted for discussing women’s rights in the context of divorce and polygamy. Rather than promoting the rule of law and constraining undemocratic interests, the Supreme Court is unaccountable and flouts the law and the new constitution.

Ultimately, a constitutional process is an opportunity to hammer out compromises that channel conflicts away from violence and into political competition. It can serve as the foundation for coalescing a nation and building a sound state. But it can equally be a means for competing interests to stake out territory, create roadblocks, or consolidate power without resolving underlying conflicts. In post-Taliban Afghanistan, where hostile factions are forced into political dialogue by external forces with their own agendas and time lines, we can only expect less than optimal outcomes.