- Contemporary

- International Affairs

- History

No one likes to go to the doctor. But for a political leader, even the news of such a trip can sound the death knell for his political career. It is small wonder therefore that a leader’s health is the most important state secret in many countries.

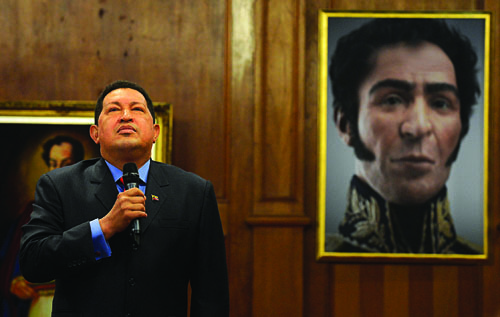

Examples of this type of secrecy abound. Not long ago, the news media were riveted by the mystery of the whereabouts of Xi Jinping, on the eve of his ascension to the post of China’s paramount leader. Xi disappeared from public view for weeks while undergoing treatment for a condition that may have been either back pain or heart troubles, depending on which reports you believe. Last fall in Venezuela, voters re-elected President Hugo Chávez, who had been less than forthcoming about his cancer diagnosis, claiming a number of dubious miraculous recoveries while periodically jetting off to Cuba for treatment. In Zimbabwe, rumors of eighty-eight-year-old President Robert Mugabe’s death turned out to be false in April, but citizens were probably not reassured by the government’s ham-handed efforts at message control.

Last year also witnessed the deaths in office of four African leaders—in Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, and Malawi—all of whom had sought treatment abroad and kept the state of their health a carefully guarded state secret before their deaths. Although the recently deceased leaders varied in age from a quite young fifty-seven to a moderately elderly seventy-eight, careful studies show that leaders, especially in undemocratic countries, outlive the life expectancy in their countries by a significant margin. Those national life expectancies, however, are already short because of the miserable way those leaders rule. Presumably, all leaders could have access to the best medical care, but getting that care can be a kiss of political death.

For heads of state, there’s also an inherent tension between maintaining good health and revealing to cronies or the public that all is not well. The difficulty, especially in autocratic systems, is that medical care can be sought only at the risk of losing one’s hold on power—a risk worth taking only in extremis. After all, “loyal” backers—even family members—remain loyal only as long as their leader can be expected to continue to deliver them power and money. Once the grim facts come to light, the inner circle begins to shop around, looking to curry favor with a likely successor. No wonder that when medical care is needed, country leaders like Mugabe or the late Meles Zenawi of Ethiopia tend to seek it in a foreign hospital, usually in a country with strict respect for patient-client confidentiality. Doctors at home are too risky—they might talk to their buddies and spread the word that their leader is gravely ill, thereby hastening the incumbent’s political, if not physical, demise. Terminal illness or even extreme old age, which is, after all, the most terminal of illnesses, are excellent indicators that the beloved leader won’t be reliable for long.

NO COUNTRY FOR DYING MEN

Politics, especially autocratic politics, requires symbiosis between leader and supporters. In return for power, perks, benefits, and privileges, a leader’s backers support him over rivals and, when necessary, suppress the people, bash in the heads of opponents real and imagined, and make life miserable for all but the elect (but not elected) few. These tasks can be unpleasant, which is why a successful leader rewards his supporters well and why corruption and graft are so prevalent in autocracies.

This symbiosis fails once either side of the relationship can no longer sustain the other. If the leader fails to take care of his loyalists, then he can expect they will plot to overthrow him. If backers won’t suppress the people on behalf of the leader, then protest and revolution threaten the entire regime. Supporters know that their leader, no matter how generous and beloved, simply cannot deliver from beyond the grave. Once their privileges and perks are in jeopardy, the inner circle looks for its next meal ticket. When the symbiosis fails, upheaval is likely and, under the right circumstances, can even have a plus side for society. After all, even many normally nasty elites may be reluctant to turn their guns on the people when the new, revolutionary leadership may be drawn from those very people.

It can therefore be wise to hedge one’s bets, just as the military did in Egypt during the 2011 uprising. Seeing that President Hosni Mubarak was very old, rumored to be seriously ill, and coming up short on his command over the amount of continued U.S. foreign aid, the Egyptian army chose to shop around to see whom among likely successors it could control. It’s far from clear whether this strategy will work out for Egypt’s generals.

Contrary to popular opinion, revolutions are more about elite choices than they are about the people. In autocratic societies, the people’s lot is usually miserable, so the desire for revolutionary change is always there. It is an opportunity to overwhelm the state that is generally lacking. As long as the leader’s coalition of critical support from the military, senior civil service, and security forces remains cohesive, dissent is met with violence, and only the courageous or foolish few protest.

Opportunity is most keenly seen when the people see that the incumbent is knocking on death’s door, and when they believe that those who keep the boss in office see this too.

People protest, and revolutions succeed, when those who can stop such popular uprisings choose not to. The shortened time horizon induced by a leader’s ill health increases the chance that regime supporters will remain passive in the face of protest. And the heightened chance of success is just what the people need to make the risk of taking to the streets worthwhile.

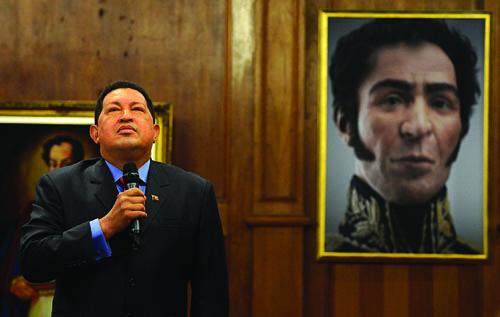

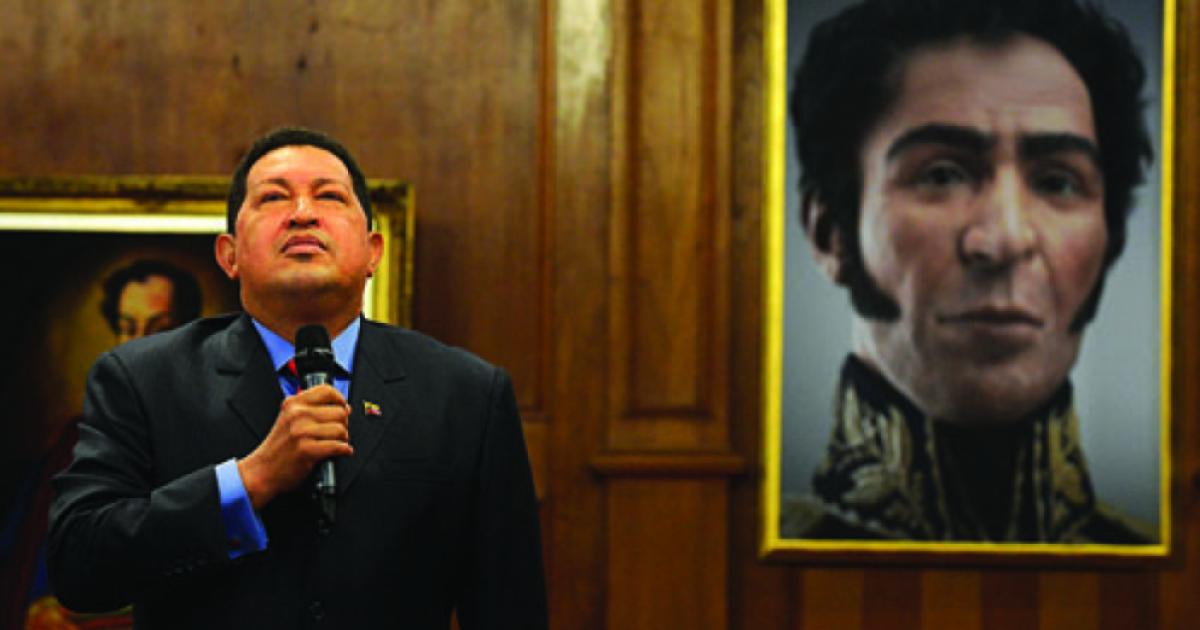

Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez, having survived both cancer and a tough re-election fight, pledges in October to be a “better president” and work with the opposition. After fourteen years in power, Chávez has had to confront simmering discontent with his socialist revolution. Among his responses has been to downplay his medical condition.

The Arab spring is a case in point. Although Mohamed Bouazizi’s death from self-immolation on January 4, 2011, served as a focal point for the disaffected people of Tunisia, in retrospect it is unlikely that revolution would have been postponed much longer. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali was already rumored to be gravely ill (and, according to some reports, went into a coma after suffering a stroke in Saudi Arabia several weeks after stepping down). The Tunisian economy was in bad shape, increasing his vulnerability. Elsewhere in the Arab world, the wounding of Yemeni President Ali Abdullah Saleh by anti-government rebels in June 2011 and his medical evacuation to Saudi Arabia were a critical turning point in his fall from office.

Libya’s Muammar Gadhafi appears to have been an exception. There are no indications that Gadhafi was ill, and many of his (extremely well-paid) supporters in fact remained loyal to the very end. NATO had to use airstrikes to prevent those loyalists from crushing the rebellion.

STRONGMEN DON’T GET SICK

The importance of a leader’s health to the success of revolution is nothing new. In 1997, Laurent Kabila’s rebel forces swept across Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, when it became evident that Mobutu Sese Seko was gravely ill. Mobutu had made the mistake of openly seeking treatment in Europe and rallying the people to celebrate his return from treatment (medical care was not up to snuff in Zaire). Ferdinand Marcos faced a similar fate in the Philippines. As his lupus progressed, his regime loyalists began to desert him, and he fell from power in 1986, dying in exile in Hawaii three years later. This too was the story of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi of Iran. As the New York Times reported on May 17, 1981, well after his fall, “There is, for instance, a hint from his cancer specialist at New York Hospital that if the shah had been treated like an ordinary patient with the same set of physicians from the onset of his illness, he might be alive today.”

But that’s not what the shah did, of course. His problem, like that of so many autocrats who must keep their loyalists content, was simple and lethal: if the extent of his cancer were known, then his supporters would almost certainly have deserted him and his overseas support could have dried up—a death sentence. Yet, without proper treatment his illness would—and eventually did—kill him. His was a sad story of a desperately sick man smuggling French doctors into Iran and sneaking into clinics under false names. But, as eventually happened, knowledge of his impending demise unraveled his rule. The Iranian people took to the streets, and the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, long in exile, returned to lead an uprising and install an Islamic regime in 1979. Much, perhaps most, of the shah’s previously loyal army stood aside, putting up little resistance.

Leaders need to appear virile and strong even in a democracy. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s inner circle kept the gravity of his serious respiratory problems secret during World War I; Franklin D. Roosevelt hid his paralysis; John F. Kennedy hid his dependence on corticosteroids. In less-democratic settings, the urgency of appearing in robust health is even more vital.

Anyone of a certain age, reflecting on Xi’s recent disappearance and return to public view in China, cannot help but remember the long period of uncertainty in China in the 1990s over whether Deng Xiaoping was alive or dead or, for that matter, in earlier years whether Mao Zedong had already expired or still clung to life. Party and succession stability in China, as in so many autocracies, requires at least a modicum of confidence that the king is not yet dead before the new king is designated the heir apparent.

For less democratic leaders, who seek to retain power for much longer periods, the appearance of good health can be even more important. Thus, in addition to a massive dose of machismo, there is political logic to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s antics. He is frequently seen bare-chested, hunting in forests, flying ultralight planes over the Arctic, and undertaking other physically strenuous acts. Such displays of virility are also a symbol of national strength for voters who recall the succession of elderly premiers who died in office during the waning years of the Soviet Union or the times of economic distress during the 1990s when the overweight, alcoholic Boris Yeltsin was in charge.

Leaders, keenly aware of the immediate risks they face when rumored to be ill, handle health crises in different ways. Theoretically, they could use the opportunity of their impending passing to improve their society and leave democratization as their legacy, but unfortunately, we are at a loss to identify a single example. They can, as noted, simply engage in secrecy. And when that fails, denial is common.

However, the combination of the Internet, mobile technologies, and advances in remote medical-diagnosis technology make it increasingly difficult for leaders to hide their health conditions. There is, for instance, an entire blog dedicated to tracking Chávez’s cancer, where alongside his dubious claims to have beaten the disease—“I thank God for allowing me to overcome difficulties, especially health, giving me life and health to be with you in this whole campaign”—are detailed discussions of every statement, treatment option, comings and goings of his doctors, change in schedule, and photograph from the campaign trail. These might appear like minutiae, but in fact hints about the president’s prognosis are politically far more important than his policy statements.

When secrecy and denial are no longer options, dynastic succession offers leaders a way to retain political loyalty. Settling the succession question ahead of time ensures continuity in the symbiosis between leaders and those who keep them in power. Backers are more vested in keeping a decrepit incumbent when they know their wealth and privileges are likely to continue even after the leader’s death. The Kim family in North Korea, Hafez al-Assad in Syria, and Fidel Castro in Cuba all used this tactic to successfully mitigate the political risks induced by declining health.

That is almost certainly why today we see the growing emergence of dynastic dictatorship. The Kim Jong Ils of the world knew where the money was and probably were happy to tell their trusted children. In this era of medical miracles, it is remarkable to think that political dynasties are making a comeback—but it’s surely no coincidence.