- Economics

- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

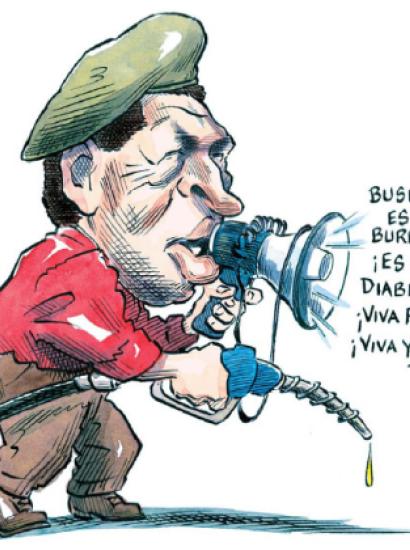

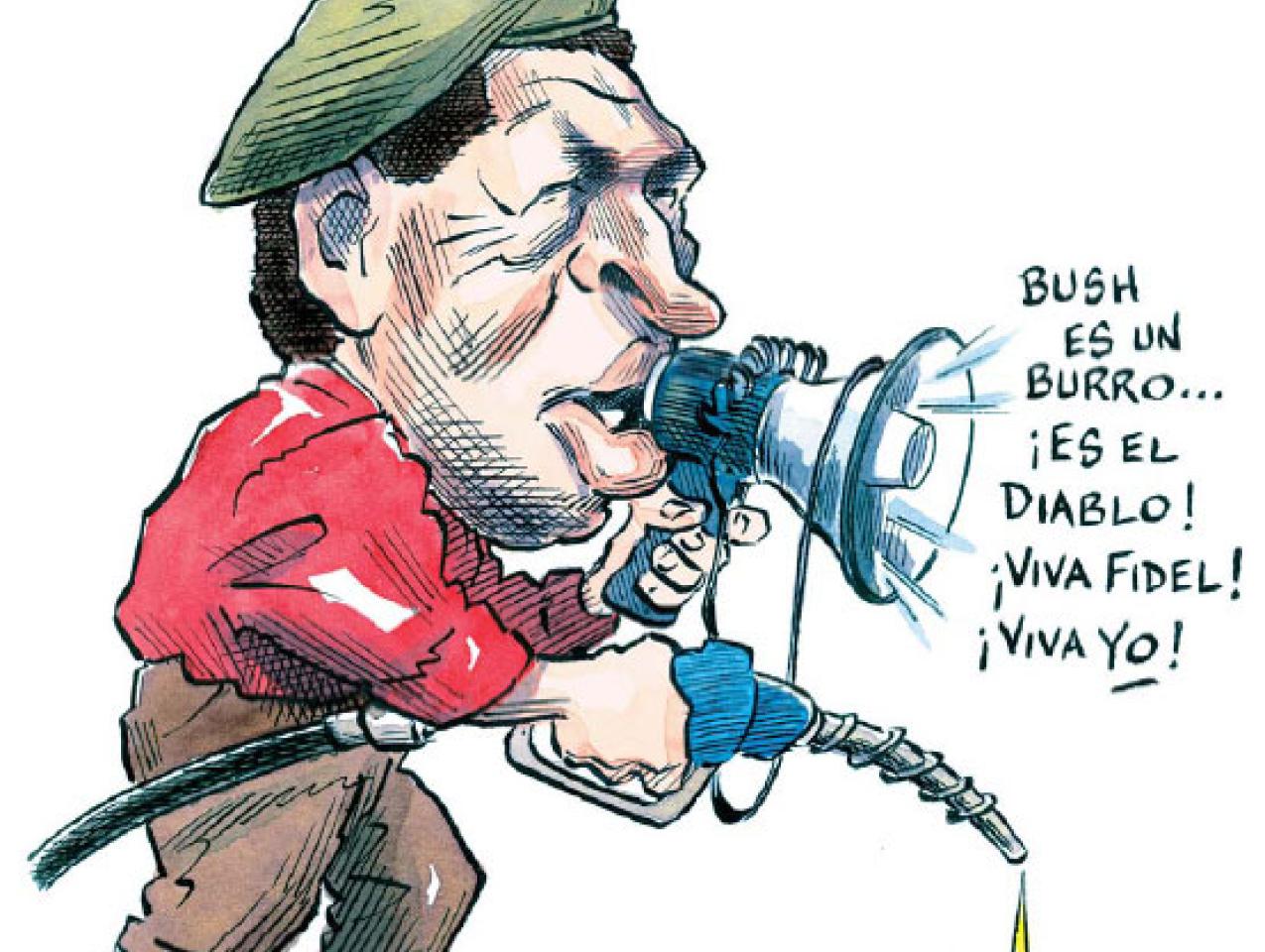

What a spectacle it was in March to see Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez chasing President Bush up the length of Latin America, from Buenos Aires to Port-au-Prince, shouting challenges and insults at the American leader and “empire.” Gilbert and Sullivan could have turned this indirect combat between the hemisphere’s two most self-consciously macho presidents into a smashing comic opera.

Bush was not in his usual macho mode. On visits to Brazil, Uruguay, Colombia, Guatemala, and Mexico, he didn’t wrestle foreign security guards, as he had done in 2004, but behaved like a diplomat discussing issues of real interest to Latins and Americans. The president focused on social justice, energy, trade, and migration, substantially downplaying the U.S. security concerns that had become the increasingly abrasive core of U.S.-Latin relations since September 11. Without ever publicly uttering the Venezuelan president’s name, Bush promoted a constructive alternative to the Chávez-style authoritarian populism that has spread in Latin America during recent years and took at least a preliminary major step forward in relations with much of the region, particularly the largest country of them all, Brazil.

In contrast, Chávez was wearing his paratrooper boots and was in no mood for diplomacy. He began his safari in Argentina with a broadside on Bush the “political cadaver.” He went on to Bolivia, Nicaragua, Jamaica, and Haiti, ceaselessly blasting Bush and “the empire” with a wild-eyed flourish, looking something like the opera fanatic in Werner Herzog’s film Fitzcarraldo. Chávez massaged anti-American crowds that rallied to him, though most were not as crowded as expected.

Polls in Latin America have found Bush slightly more popular personally than Chávez, but many Latins nonetheless resonate in varying degrees to much of what the Venezuelan has to say, and much more so now than 10 years ago. He has eagerly taken the role Fidel Castro held for decades as the region’s foremost anti-American purveyor in chief of false hope. If one flushes out the incessant ad hominem attacks on Bush and other American leaders, Chávez’s message can be boiled down to three points:

- Most of Latin America is plagued by seemingly intractable poverty and inequality.

- The United States and entrenched domestic elites and institutions are responsible for this.

- Chávez’s “twenty-first-century socialism” is the hope for the impoverished masses who seek a free and prosperous future.

He is dead right on the first point, partly right on the second, and dead wrong on the third.

PATERNALISM DISGUISED AS POPULISM

Exploitation, inequality, and extreme poverty, which have characterized Latin America since pre-Columbian times, were institutionalized by the Spanish and Portuguese colonial governments beginning more than five centuries ago. Since independence, most regimes, whether autocracies, military dictatorships, or democracies, have failed to respond seriously to popular needs. Thus populism seems to be a life jacket for drowning people and nations and has won presidential elections in Venezuela, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nicaragua, and near wins in Peru and Mexico.

Chávez is a newfangled old-fashioned caudillo who is far more inclined toward faith than objective analysis. That faith is in Himself, the new messiah whose gospel is twenty-first-century socialism. Chávez talks of socialism, but his style is left-fascism; his sermons and actions lead to authoritarian paternalism, and not the nurturing sort. Its essence is simple: “Go home, gringo, and leave Latin America to Latins—and to Me.”

This is the earthly salvation offered by every Chavista messiah in Latin America today. But tragically, Chávez’s gospel is just corked wine in a new bottle. Twenty-first-century socialism is an aggressive and globalized rehash of the type of rule that caused and sustained Latin America’s underdevelopment over the centuries. It is the latest adaptation of the late fifteenth-century Iberian view of God, man, and institutions that over many centuries made and kept Latin America the most unequal region on earth.

Chávez’s “socialism” may survive for a while at home, where his consolidation of power has speeded up since Venezuelans renewed his electoral “mandate” in December 2006. There he can throw multibillions of petro-dollars into usually failed or failing programs that may survive as long as the dollars flow in, though some in the opposition told me in Caracas in February that the economy is in such bad shape they don’t think he can last two more years. Other countries that have fallen or will fall under the spell of a Chavista messiah and impossible expectations, but lack the petro-billions, will crash more quickly, unless they just smolder indefinitely in more of the hopelessness that led them to Chavismo in the first place.

The U.S.-Latin BACKSTORY

U.S. policy in the hemisphere is strongly affected by three points.

First, Washington has traditionally had little real interest in Latin America beyond economics in its various forms. Although the Bush administration denies it, most of Latin America’s real problems have received less attention in Washington since September 11—some bilateral trade and the stabilization of Colombia being important exceptions.

Second, in recent years Washington’s constant emphasis on security has led to punitive, often self-isolating policies. In fact, our most counterproductive policies in Latin America predate Bush, though he has continued or sometimes altered them, including the indifference toward Latin America, the embargo of Cuba, hypocritical immigration policies, and the disastrous “drug war.” All these have in various ways undercut sincere but usually halfhearted U.S. efforts to support the development and consolidation of democratic political, judicial, and other institutions.

Third, there is widespread opposition to Bush’s foreign policies in general, particularly the war in Iraq. To detractors, these seem to prove Washington’s basically predatory nature.

On their March trips, both presidents cited what they called very generous aid packages, of several billion dollars, in recent years. But this aid is insignificant, except for propaganda purposes, when compared to other forms of economic interaction, where Venezuela hardly rates at all. Incomparably more constructive are investments, trade, and remittances, which of course the Chavistas and many traditionalists discount or condemn as modern foreign exploitation. These include U.S. foreign direct investments of more than $350 billion, 20 times the U.S. investment in China. More than 1.6 million Latin Americans are employed in businesses with majority U.S. ownership. Latin exports to the United States last year topped $330 billion, substantially more than Chinese exports to the United States, and remittances sent home by Latins working in the States amounted to more than $60 billion. And as for trade, Chávez pays for most of his anti-American “socialism” with the billions of dollars he makes from oil sales to the United States at astronomical market prices.

WHAT LATIN AMERICA REALLY NEEDS

The underlying problems in Latin America today, as throughout history, are the seemingly intractable poverty and inequality we, Chávez, and most Latins lament. Many in the United States are concerned at the scarcity of opportunities and social justice in the region, and not just because the absence of those qualities contributes directly to illegal migration to the States and to the weakness of intellectual property and legality in general. Latins themselves repeatedly say in polls that they want individual and national development, meaning much better jobs, housing, and education, and equal access to opportunities and protection under the law. They also express their repeated frustration with the failures of all forms of government to deliver the goods or to foster the education and opportunities to allow people themselves to deliver the goods.

Thus Latin America’s real needs now, as in centuries past, are precisely the opposite of Chavista authoritarian socialism. It needs greater pluralism, economic liberalization, truly free trade, much higher-quality governance, greatly expanded and improved education, and more opportunity under impartial law. These policies must be put into practice in individual countries by their own leaders with popular insistence and support. Latin America is not likely to have reforms in an “Asian” mold, for those have often relied on superior leaders combining vision, realism, and patience who have not turned up often in the Latin world. Up to now, most Latins have been unwilling, which is their choice, or unable to significantly modify traditional cultural or institutional norms that prevent their societies from growing like the Asian “tigers” and “dragons.” Thus, much of Latin America is rapidly falling behind other parts of the developing world, particularly Asia.

Latin America also persists in blaming the United States—and, increasingly, China—for the failures caused mainly by the region’s own cultures, institutions, and leaders. Chávez specializes in this but many of his predecessors have ignobly led the way. One example that transcends Chávez is the demagogic blaming of the United States for the shortfalls and failures of so many reforms in the 1990s. Indeed, in 2001–02 Argentina, which during the previous decade was seemingly the most pro-American and successful development model of them all, plunged into economic and social chaos. In just a few weeks five presidents scurried through the presidential palace, the government declared the largest debt default in world history, poverty mushroomed, and scapegoating of the United States exploded into the most virulent anti-Americanism in the hemisphere.

The United States, China, and even Spain cannot be seriously blamed for Latin America’s continuing poverty and inequalities. Kishore Mahbubani, one of Singapore’s foremost diplomats, drew up some “commandments” for countries seeking development, taken in large part from the experiences of his own small and very successful country. The first is, don’t blame others for your past failures. Seeking scapegoats prevents critical self-examination and thus guarantees continuing failure. It is time for Latins to stop blaming others for their problems and take control of their present and future. Chávez and his followers are marching into the past.

U.S. Policy in Transition?

Although U.S. policy itself cannot erase this Latin tradition of avoiding responsibility, it can foster reform, if Latins want it enough to sacrifice for it. Such reform also would serve U.S. interests. Besides changing some of the counterproductive U.S. policies toward Latin America, which no recent president yet has been able to do, there are other steps we can take.

President Bush’s newly discovered interest in social justice and other issues at the top of Latin agendas is a big step in the right direction. His 2007 trip was far more effective than the one to the APEC forum in Santiago, Chile, in late 2004, when he struck out with Latin public opinion while a much more personable Chinese President Hu Jintao was hitting a home run.

Bush also seems to be taking seriously the need to draw the region’s moderate leftist governments, particularly but not only the one in Brazil, away from their neutrality about Chávez’s debilitating demagoguery and populism. Traditional Latin leftists running several countries have been reluctant to criticize populist “leftists” like Chávez, even though the moderate leftists have the most to lose from the spread of Chavismo. To the degree that these moderate leftist countries are succeeding economically, they, along with Mexico, Colombia, and others, owe much more to Milton Friedman than to Karl Marx. In varying degrees, they accept that free trade and markets offer the only productive alternative to Chávez’s scapegoating, paternalistic recipe.

Bush’s March trip was the most potentially constructive action he had taken toward Latin America in years. Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva met with him in Brazil and then again several weeks later in the United States, and cooperative programs for the production of ethanol were on the agenda. Part of Silva’s incentive in this may be making Brazil the “big” country of Latin America, instead of Venezuela, which is what Chávez is rather successfully pursuing. In Colombia (and Peru and Panama as well), significant progress in the antiguerrilla war must now be backed up with immediate passage of trade legislation by the U.S. Congress. And serious attention to immigration, a focus that disappeared after the September 11 attacks, must again be the centerpiece of relations with Mexico. But getting Latin America’s moderate socialists and others to even tacitly side with the United States on these critical issues will demand U.S. actions, not just words, to prove willingness to give as well as take.

Despite his links to Iran and Russia, Chávez is primarily a threat not to the United States but to the well-being of Latin Americans. His “socialism” will further reduce their chances of prospering or even surviving in the modern world—and that is what collides most seriously with the interests of the United States. Thus our strategy in combating him and his ideas is more constructive attention to the region as a whole, not direct combat with Caracas.