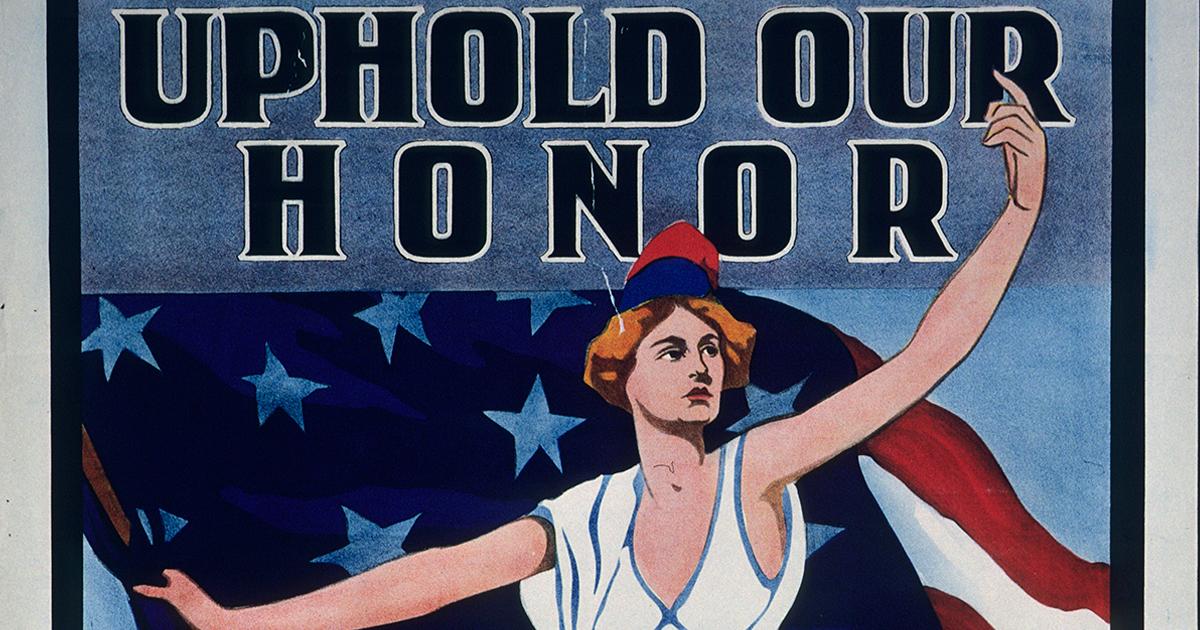

Anyone who teaches a class on the values of Homer, the way of the samurai, or the dueling culture of, say, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr, knows how hard it is to explain honor nowadays. Honor is not a word much in ordinary use in our postmodern, civilian, technocratic culture. Yet over the course of human history, honor has been the coin of the realm; indeed, perhaps its most valuable denomination. For men and women who serve in fire and police departments and, above all, in the military, it still is.

The United States’ highest military award, for example, is the Medal of Honor. The most recent recipient, earlier this year, is Colonel Paris D. Davis. As a Special Forces officer in 1965 in Vietnam he led a charge to neutralize enemy emplacements, engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the foe, and saved the lives of three American soldiers. Despite suffering multiple wounds in a 19-hour battle, Capt. Davis, as he then was, refused to leave the field until his men were brought to safety. He was also awarded the rare distinction of a second high honor, the Soldier’s Medal for heroism: he pulled a soldier from a burning truck, just before it exploded, thereby saving the man’s life.

History has many earlier examples of military men who put their honor first even at the risk of their lives. Three cases come from the month of August.

Around the end of August 480 B.C., King Leonidas of Sparta along with all but two of his 300 men stood, fought, and died at the pass of Thermopylae in central Greece rather than surrender to an invading Persian army. Leonidas and his men had a chance to escape but decided to stay. Our best source, Herodotus, says that the king felt it would “not be fitting” and “not noble” for the Spartans to leave, although he did dismiss most of his allies. Leonidas also wanted to “leave behind great glory.” It seems that the Delphic Oracle had prophesied that unless the king died, his country, Sparta, would be destroyed by the invaders. So, the king gave up his life, and his men fell with him. Although they didn’t stop the enemy from marching south, they gave him a savage beating over three days. And they galvanized the Greek spirit of resistance that eventually won the war.

A second example comes from 1944. On August 26 of that year, Charles De Gaulle marched in the front ranks of a parade of French troops down the Champs Elysées in Paris. Only the day before, the German commander had surrendered the city after four years of occupation. De Gaulle was rarely an easy man to deal with and sometimes one whose policies appalled many observers. Yet his greatness is unquestioned for many reasons, above all, due to his leadership of Free France during World War II. From his exile in London, De Gaulle saved the honor of France. In August 1944 he was a general as well as the president of France’s provisional government. As he marched down the Champs Elysées on that day in August 1944, he wore his military uniform. At six foot five inches tall, De Gaulle was hard to miss. He made a fine target, therefore, for German snipers. Although they shot at the crowd, De Gaulle didn’t flinch. He displayed similar courage later that day when shots were heard in Notre Dame Cathedral in the middle of a prayer of thanks.

France needed a symbol of courage. Despite the bravery of a few in the Resistance, many if not most Frenchmen had made their peace with the Occupation, and some embraced it. De Gaulle knew what to do. He put the honor of a nation before his own personal safety.

The third and final historical example comes from the American Revolution. On the night of August 29, 1776, the Continental Army began pulling out from Brooklyn. In late June and July, British forces sailed into New York harbor with an enormous fleet of 400 ships, including about 75 warships. British military manpower outnumbered the Americans by about two to one. New York City was of great strategic value; Washington planned to defend it not from Manhattan but from Brooklyn, where his troops would be less at the mercy of Britain’s command of the sea. Or so he thought. But when the British landed in Brooklyn they soon attacked and won a major victory. They drove the Americans back to Brooklyn Heights, with their backs to the water. The British laid siege. Washington and his commanders then decided to withdraw.

In contrast to their poor performance in battle, Washington’s troops carried out the retreat masterfully. They managed to get all 9,000 soldiers and their supplies across the East River to safety in Manhattan. Standing on the Brooklyn shore today in the shadow of the bridges, at the spot where the evacuation embarked, it is hard to imagine the drama that once took place there. The evacuation saved the Continental Army, and, with it, the Revolution.

But consider the last act. Despite the proximity of the enemy, Washington did not depart until every single one of his soldiers had escaped. Washington was the last man to leave Brooklyn. There was no time to spare, as the British guns could be heard firing as the boat pushed off. Washington risked his own life. Like Davis in Vietnam, two centuries later, he put the safety of his men first. Honor demanded no less.

Honor may seem old-fashioned, but it lives on. It shines through the cracks in today’s bureaucratic, surveillance society. Honor draws us to deeds that are often cantankerous, occasionally heroic, and always resistant to expression in binary bits. Honor is music in a workaday world; honor is freedom.

Barry Strauss is the Bryce and Edith M. Bowmar Professor in Humanistic Studies at Cornell University, Corliss Page Dean Visiting Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and author most recently of THE WAR THAT MADE THE ROMAN EMPIRE: Antony, Cleopatra, and Octavian at Actium (Simon & Schuster).