- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

The United States is often criticized for favoring a multilateral approach in the six-party talks aimed at reversing North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons. Never mind that many of those critics repeatedly castigated Washington for supposedly spurning the multilateral approach in favor of unilateral action in Iraq; consistency is hardly to be expected in these matters.

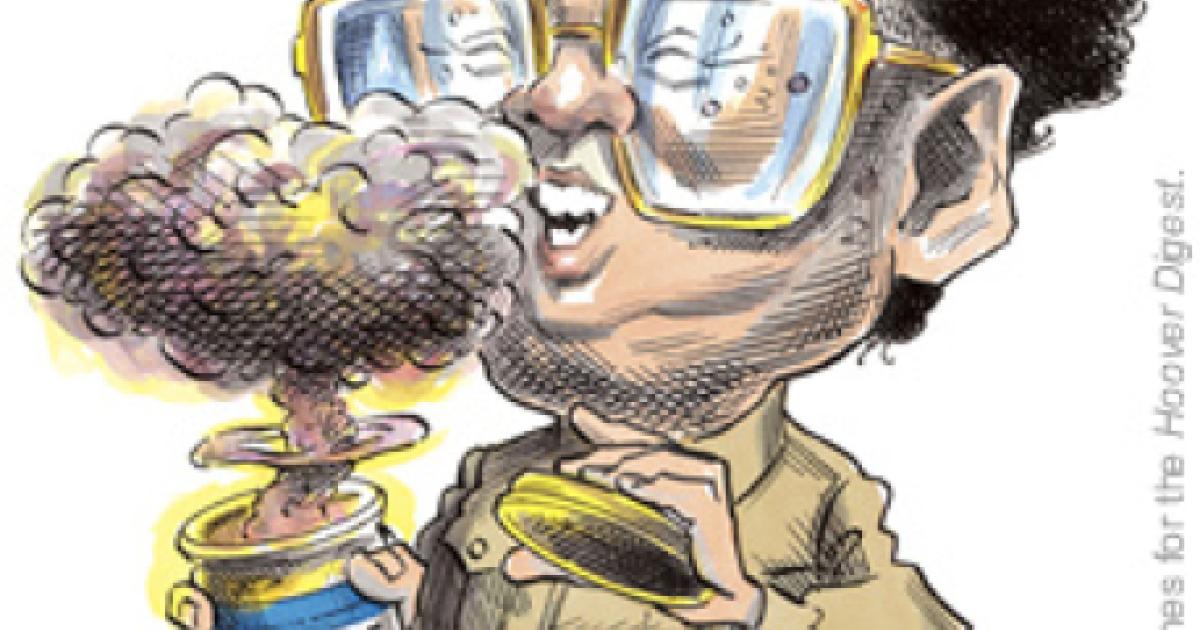

When it comes to North Korea, the critics favor what they call a bilateral approach but what in reality amounts to a unilateral one. Under this scenario, the United States would engage in direct negotiations with Kim Jong Il’s regime, relegating the other four parties—China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia—to a more passive role. Even in its more nuanced form, the critics’ argument is that the six-party talks are no more than a facade and that any serious progress toward ending North Korea’s nuclear programs can only come through unilateral negotiations with Washington.

Yet the reality is very different. North Korea poses a serious threat to the vital interests of each of the five other parties. It already possesses sufficient plutonium and highly enriched uranium to make—or already have made—anywhere from six to eight nuclear weapons and has the missile capability to launch these over distances of up to 5,500 miles. Still more worrisome is the prospect that North Korea might sell nuclear materials to al Qaeda or other financially well-heeled terrorist groups. According to recent reports, North Korea may already have engaged in such transactions with Libya. Kim Jong Il’s regime is so badly strapped for cash that its survival may depend on rapid access to substantial outside funding.

The case for a multilateral approach rests on the fact that the burden of dealing with that threat should be shared by the five countries because their separate and vital national interests are all at stake—China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia, in addition to the United States.

China’s interests in a non-nuclear North Korea focus on preventing nuclear proliferation elsewhere in Asia—especially Japan, South Korea, and possibly even Taiwan. All might be tempted to move in this direction if faced by a North Korean nuclear threat. In addition, China has its own battle with Muslim extremists in the far western province of Xinjiang, and the last thing Beijing wants is for there to be any danger of Uighur terrorists obtaining nuclear materials from a proliferating Pyongyang.

Russia too fears that North Korean nuclear material might find its way into the hands of Muslim militants—in its case the Chechnya separatists whose willingness to resort to any means, no matter how horrific, was demonstrated by the massacre of more than 300 children in Beslan last September 1. U.S. interests in preventing proliferation by Pyongyang are thus closely linked to Chinese and Russian concerns that North Korea might become a channel for leaking nuclear materials to Muslim terrorists.

Japan’s interests in a non-nuclear North Korea are equally strong. Tokyo is keenly aware of the ingrained Korean resentment and hostility toward Japan. A North Korea with nuclear weapons, coupled with its ability to deliver them, might lead Japanese policymakers to doubt the adequacy of the U.S. protective nuclear umbrella. That could, in turn, prompt growing pressure for Tokyo to acquire its own nuclear deterrent, something that it already has ample technical and financial means to accomplish.

Even in South Korea, where many believe they would not be the target of North Korean nuclear weapons, the predominant view in the policy community is that a nuclear Pyongyang would profoundly disrupt Northeast Asia’s security balance and thus imperil the stability on which South Korea’s continued progress and economic growth depend.

The other four nations in the six-party talks—China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia—thus have their own interests in stopping North Korea’s nuclear programs, which are at least as strong as those of the United States. Where a jointly favored or collective benefit is sought by a group of countries, the crucial bottom line for their collaborative efforts is how the burden of securing this shared benefit should be shared. Multilateral management of the effort to halt and reverse North Korean nuclear development is essential. Whether and how much to use carrots and sticks requires collective, multilateral decisions.

For example, whether to use carrots in the form, say, of trade liberalization with and by North Korea or credit installments extended to North Korea and collateralized by claims on its mineral resources, is a decision that must be arrived at multilaterally. Similarly, whether sticks, in the form of inspecting and monitoring possible North Korean nuclear installations and strengthening the Proliferation Security Initiative to encompass surface and air surveillance and interdiction of suspected exports of nuclear materials and weapon-system components, should be invoked is a decision that also needs to be reached collectively.

Securing a collective benefit—in this case, a non-nuclear North Korea—entails a collective burden. That’s why it’s only right to expect China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia to play their part and wrong to leave the entire burden on the United States.