- World

- Contemporary

- Campaigns & Elections

- The Presidency

- History

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

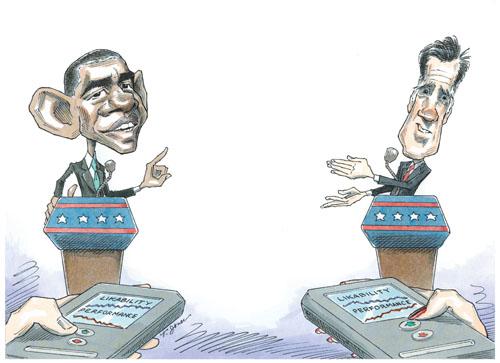

Recent polls report that President Obama is more “likable” than Mitt Romney, his challenger, and that his “favorable to unfavorable” ratio is more positive. Other things being equal, it is no doubt better for a candidate to be liked than disliked, but when other things are not equal, historical data suggest that a candidate’s likability is a relatively minor factor in deciding modern presidential elections.

In the 2000 election, Democrat Al Gore embarrassed political-science election forecasters. Although he narrowly won the popular vote, he badly underperformed expectations for elections during periods of peace and prosperity. At a major national convention two months before the election, a panel of seven forecasters had predicted Gore would win between 53 percent and 60 percent of the two-party vote. Among the post-mortems, a prominent explanation for Gore’s negative accomplishment was the personal one: voters simply did not like him. Gore was an arrogant know-it-all who continually reinvented himself, a serial exaggerator, the kind of boy who would remind the teacher that she had forgotten to assign homework.

In a postelection research report published in the British Journal of Political Science nearly a decade ago, Samuel Abrams, Jeremy Pope, and I tried to evaluate that and other explanations for Gore’s defeat. We turned to the American National Election Studies, which since 1952 have queried Americans about their views of the opposing candidates. Citizens are invited to say anything that might make them vote for the Democrat, and then against him; the Republican is treated the same. Respondents answer these four questions in their own words (up to five answers are recorded verbatim for each question, but few people offer more than two), and the statements are later coded into categories, which by now number more than seven hundred.

We divided the response codes into two broad categories: personal qualities like intelligent/stupid, sincere/insincere, inspiring/dull, and so forth, and everything else, including the candidate’s record, policy positions, and supporting groups, and summed them up into measures of net favorability. The measure of personal qualities falls somewhere between those most commonly used in today’s polling. It is broader than “likability”—logically, one could dislike a candidate one viewed as intelligent, sincere, and inspiring, although that seems unlikely. And it is narrower than counts of favorables and unfavorables, which include policy and performance considerations as well as personal qualities.

IT TOOK TIME TO LIKE IKE

Our analysis revealed a number of surprises. What journalists and historians wrote about the candidates after the elections was sometimes considerably at odds with what Americans had said about the candidates before the elections. For example, in 1952 the public rated Adlai Stevenson slightly higher than Dwight D. Eisenhower on the personal dimension. Eisenhower was viewed as the strong leader who won the war in Europe. “I like Ike” was a better description of 1956 than 1952. Similarly, in 1960 the public rated Richard M. Nixon ever so slightly higher than John F. Kennedy. As one prominent political scientist wrote at the time, “If the eventual account given by the political histories is that Nixon was a weak candidate in 1960, it will be largely myth.” Kennedy’s charisma developed after the election.

Overall, in the thirteen presidential elections held from 1952 to 2000, Republican candidates won four of the six in which they had higher personal ratings than the Democrats, while Democratic candidates lost four of the seven elections in which they had higher ratings than the Republicans. Not much evidence of a big likability effect here.

In most elections, however, voters did not give a large personal edge to either candidate. In four elections, they did.

In 1964, Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson rolled over Barry Goldwater, the second-lowest-rated Republican on the personal dimension in the thirteen elections. Would a somewhat more likable Republican (Nelson Rockefeller? William Scranton? George Romney?) have done better? Possibly. Better enough to win? Doubtful. Johnson was the highest-rated Democrat of the half-century on the record, positions, and groups dimension. The 1972 election was the reverse of 1964: Nixon trampled George S. McGovern, the second-lowest-rated Democrat in personal terms. But for Nixon, too, the record and positions dimension dominated the personal.

The remaining two elections featured the lowest-rated Republican and Democratic candidates on the personal dimension, and partly as a consequence, the widest disparities between the personal ratings of the two candidates. In both cases the candidate lacking in the personal dimension won.

Jimmy Carter’s 1980 job approval was flirting with lows established by Harry S. Truman, Nixon, and later, George W. Bush, but the electorate rated Carter’s personal qualities as the highest of the Democratic candidates between 1952 and 2000. The same electorate rated Ronald Reagan the lowest of the Republican candidates. The Ronald Reagan of October 1980 was not the Reagan of “morning again in America” in 1984, let alone the beloved focus of national mourning in 2004. Many Americans saw the 1980 Reagan as uninformed, reckless, and given to gaffes and wild claims. But despite their misgivings about Reagan, and their view that Carter was a peach of a guy personally, voters opted against four more years of Carter.

Finally, the 1996 election supports the 1980 indication that personal qualities matter far less than national conditions and the experience, record, and positions of the candidates. In personal terms, Bill Clinton in 1996 was the lowest-rated candidate—Democrat or Republican—in the thirteen elections. Contrary to popular commentary, he was not a “Teflon president”—his checkered personal history was reflected in low personal ratings. But he was the opposite of Carter: his job-performance ratings stayed high even while his personal ratings tanked.

In 1980, citizens decided to vote out a personally admired president in favor of a risky alternative. In 1996, they opted to retain a president they viewed as personally sleazy but doing a good job. In each case the voters put performance and positions above personal qualities.

ISSUES OVERRULE PERSONALITY

Although our original analysis ended with the 2000 election, I do not believe that the results of the 2004 and 2008 elections affect the findings. George W. Bush versus John Kerry puts me in mind of George Bush versus Michael Dukakis in 1988. As for 2008, with the Republican candidate weighed down by an unpopular war and economic meltdown, any advantage of Barack Obama’s persona was icing on the electoral cake.

Judging by the historical evidence, I doubt that Romney’s purported likability deficit will play a significant role in the imminent election. My (admittedly impressionistic) view is that Romney is in the same ballpark as Nixon or the first President Bush. If Romney loses, it will be because the public believes that Obama has done a good enough job to continue or that Romney has not advanced a credible recovery program. “Voters didn’t like my personality” is a loser’s excuse.

Gore might be happy to hear that we found no evidence that his underperformance in 2000 reflected his personal unattractiveness. His personal evaluations were slightly negative and lower than Bush’s, but well within the historical range. Our analysis indicated that Gore lost because he did not get the normal amount of credit for the good economy, because the electorate perceived him as farther to the left than Clinton, and because—unfairly—he was tarnished by Bill Clinton’s personal failings.