- Security & Defense

- US Defense

U.S.-led Coalition forces have made significant and hard-earned progress building the capacity of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) to take the lead in providing the security needed to bring stability, development, and governance to this persistently impoverished country with little history of effective centralized rule. Rampant corruption, a resurgent Taliban, limited penetration of the central government in the country’s largely rural population, and waning enthusiasm among international aid donors, however, make for a daunting way ahead. On the eve of the next presidential elections this spring and the precipitous drawdown of U.S. and NATO forces—potentially to zero—by the end of the year, a number of pressing questions remain. Will the Afghan National Security Forces have the capacity to secure their population and quell the insurgency? At what pace can Coalition forces pull out without “pulling the rug out” from under the security situation? Can the Kabul government survive post-foreign troop withdrawal?

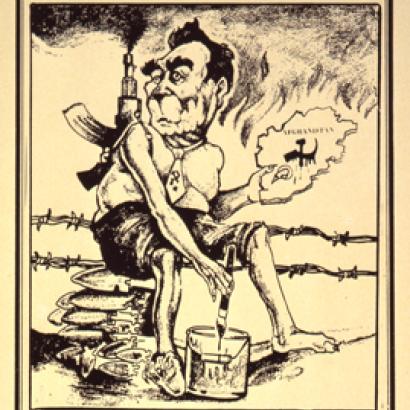

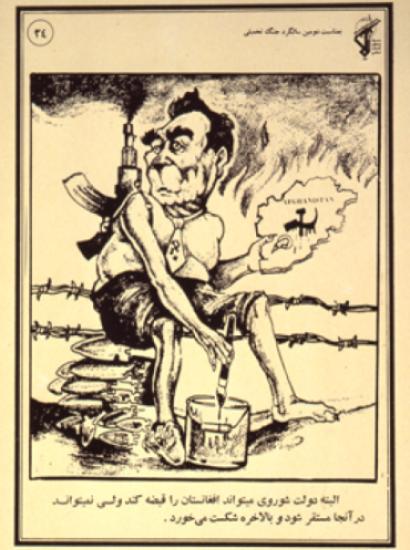

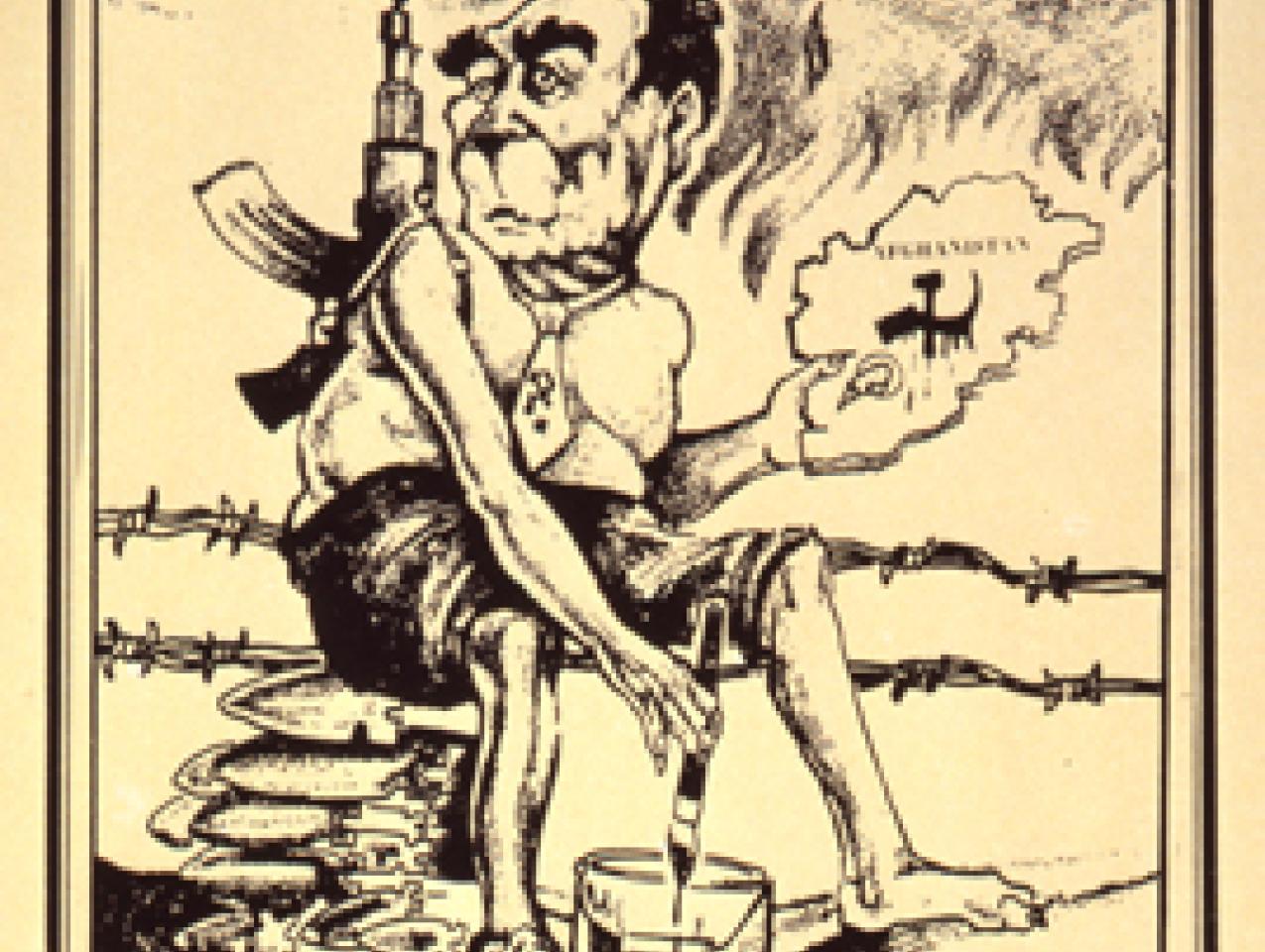

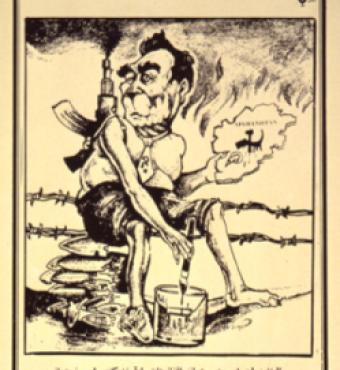

The answers to these questions even at this late date are unclear. Historical precedent provides some basis for optimism, however, that Afghanistan’s security forces, with continued aid and support from the international community, may—at least nominally—carry out their mission to secure the country and prevent a return of Taliban rule after U.S. and NATO forces leave. Following the redeployment of Soviet combat troops from Afghanistan in early 1989, for example, the security situation did not entirely collapse despite the many dire predictions at the time.1 In fact, with continued military assistance and enablers such as combat aviation assets, the Afghan security forces were able to prevent the collapse of Najibullah’s government for nearly three years—up until the critical aid and assistance was cutoff with the fall of the Soviet Union.2

In the Soviet case, the ability for ongoing economic aid to sustain the Afghan regime they left behind—staving off total collapse and outliving even the Soviet Union itself—is a significant success of the Soviet exit strategy that is often overshadowed by Najibullah’s bloody demise and the civil war that erupted soon after. Given this precedent, the interests of the U.S., NATO, and other members of the international community with a stake in the security and stability of Afghanistan are well advised to continue to provide security assistance and economic aid to Afghanistan well after the withdrawal of military forces.

Assessing ANSF capabilities relative to the standards of developed western militaries can be disheartening and cause pessimism about their anticipated capabilities post-U.S. troop withdrawal. Readiness issues, high desertion rates, limited organic enabling assets, poor accountability mechanisms, illiteracy, and other problematic factors can make it challenging to maintain a positive outlook for Afghanistan’s security environment post-transition.

Encouragingly, however, the more relevant standard to hold Afghanistan’s security forces to as the U.S. and NATO withdraw is whether they are more capable and proficient than the Taliban and other likely security threats Afghanistan might face. This standard is arguably achievable even with the well-documented ANSF weaknesses and shortcomings. To the credit of U.S. and NATO training and mentoring efforts to date, the ANSF is now taking the lead in security operations, holding their ground in head-to-head confrontations with the Taliban, and overall are prevailing against a variety of insurgent threats around the country. Importantly, these successes are in many cases dependent on the critical support of key Coalition Force enablers such as intelligence resources, mobility assets, and special operations forces.3

Of concern, however, is the likelihood that the huge investments made in Afghanistan by the international community have led to the “purchasing” of a certain amount of cooperation among various leaders and stakeholders and held at bay some of the centrifugal forces such as competition among rival warlords. As U.S. and foreign investments are inevitably reduced and these incentives diminish, this cooperation will be harder to sustain. Given this, perhaps the biggest threat to the security of the country after the departure of U.S. forces hinges less on the capabilities of its security forces and more on its internal cohesion and the potential for ethnic divisions to fracture it.

Of even more concern is the sobering truism that, ultimately, counterinsurgency campaigns can only be as good as the government they support. Even the best, most effective security forces left behind when the U.S. departs cannot compensate long for failures in governance as they cannot “sell” a product—support for a central government—that most Afghans are reluctant to “buy.”

1. Soviet troops trained and equipped the Afghan forces, and then turned over a number of major population centers for the Afghans to defend, including the garrisons of Jelalabad, Gardez, Ghazni, Kandahar, Lashkar Gah, Kunduz, and Faizabad, supported critically by Soviet aviation assets. While ceding much control of the countryside, the Soviet-trained Afghan security forces were able to secure major population centers and stave off a collapse of security post-Soviet withdrawal.

2. A rich primary source archive chronicling the Soviet experiences in Afghanistan as described by Politburo members and other senior officials can be found at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution Library and Archives, Fond 89. For a description of the relevant information in this unique archive, see Katya Drozdova, “Solving the Afghanistan Puzzle,” Hoover Digest (2010 no. 4), available at http://www.hoover.org/research/solving-afghanistan-puzzle.

3. Holding cleared areas, however, remains particularly challenging for Afghan national security forces. U.S. Special Forces-led efforts to field locally recruited part-time security forces—known as Afghan Local Police (ALP)—has been particularly effective in helping to secure the rural population in areas most at risk of falling under Taliban influence. Beyond the appreciable benefits this program provides in extending security, it also serves as a mechanism that can harness the potential of local forces to build rapport with the community and provide important local information to regular ANA and ANP units operating in the same vicinity. Additionally, it can serve as a potential resource to facilitate reintegration efforts key to making progress in the campaign.