Abstract

While the so-called “Arab Spring” was an awakening for the region’s people and its powerholders, the events of 2010–2011 changed the trajectory of innovation and entrepreneurship only slightly and in specific, local contexts. This paper endeavors to compare Egypt, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) with three major objectives in mind.

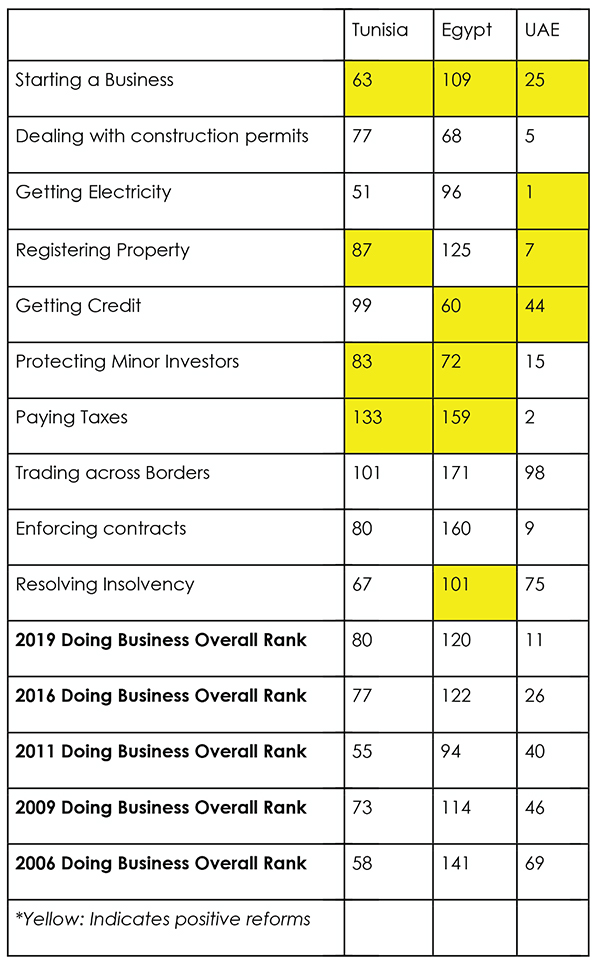

First, the paper reviews the history of the region, and in particular the reasons for and impact of its late and uneven development. Second, it demonstrates that the general business and innovation trends across the region remained mostly unaffected by the “Arab Spring.” Drawing upon the Doing Business World Bank data, we find that among the three countries under study, the UAE has made steady improvements, while Egypt and Tunisia have remained relatively constant. Examining each case further, it appears as though government support for entrepreneurialism alone only goes so far, though the conditions for doing business are contingent on the removal of government constraints. Civil society (Tunisia) and the private sector (UAE and Egypt) are also important actors albeit not in quite the same way.

For the UAE, “angel investors” have made a significant difference, though civil society has yet to find its footing. In Tunisia, civil society was a driving force behind recent achievements, perhaps notably vis-à-vis the Startup Act. In Egypt, civil society remains closed under the Sisi regime, yet some initiatives by the private sector provide a silver lining to its post-2011 context and have influenced the government to pay new attention to the private sector as integral to its economic (and political) vitality and survival.

Notably, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) kept the engine of the Egyptian economy going during its uprisings when the government was mostly shut down. Finally, the paper suggests that Tunisia may soon prove to be an outlier in terms of the new opportunities posed by the “revolution” in both the altered state of corruption combined with government and civil society attention paid to the new entrepreneurial landscape.

Introduction

While the so-called “Arab Spring” was an awakening for the region’s people and its powerholders, the events of 2010–2011 changed the trajectory of innovation and entrepreneurship only slightly and in specific, local contexts. That is, while this series of revolutionary events were a “critical juncture” for the politics of the region, they did not affect the overall business environment as much as many had hoped. Rather, the great leap in support for entrepreneurialism occurred around the new millennium. A 2011 study on “Accelerating Entrepreneurship in the Arab World” identified around 150 initiatives that fostered entrepreneurialism in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, including tech incubators, civil society organizations, networking associations, and academic university programs dedicated to entrepreneurship, among others. One of the central findings of the study was that the pace of growth increased drastically from 2000 onwards, from approximately 1.5 initiatives per year in the period 1974–1999 to about 10 per year thereafter, indicating that “MENA governments have come to understand the value of entrepreneurship and its importance in growing economies” (Accelerating Entrepreneurship in the Arab World, 2011).

Thus, ascribing a new “Silicon Valley” to the MENA region is premature. Indeed, to do so would be to neglect an important distinction between an increase in entrepreneurialism, on the one hand, and innovation, on the other. However, to say that the “Arab Spring” had no impact on business development and entrepreneurship would be incorrect. Throughout the countries of the Arab Middle East and North Africa, the uprisings posed challenges to authorities and invited opportunities in local contexts.

This paper endeavors to compare Egypt, Tunisia, and the UAE with three major objectives in mind. First, the paper reviews the history of the region, and in particular the reasons for and impact of its late and uneven development. Second, it demonstrates that the general business and innovation trends across the region remained mostly unaffected by the “Arab Spring.” Drawing upon the Doing Business World Bank data, we find that among the three countries under study, the UAE has made steady improvements, while Egypt and Tunisia have remained relatively constant. Examining each case further, it appears as though government support for entrepreneurialism alone only goes so far, though the conditions for doing business are contingent on the removal of government constraints. Civil society (Tunisia) and the private sector (UAE and Egypt) are also important actors albeit not in quite the same way. For the UAE, “angel investors” have made a significant difference, though civil society has yet to find its footing. In Tunisia, civil society was a driving force behind recent achievements, perhaps notably vis-à-vis the Startup Act. In Egypt, civil society remains closed under the Sisi regime, yet some initiatives by the private sector provide a silver lining to its post-2011 context and have influenced the government to pay new attention to the private sector as integral to its economic (and political) vitality and survival. Notably, SMEs kept the engine of the Egyptian economy going during its uprisings when the government was mostly shut down. Finally, the paper suggests that Tunisia may soon prove to be an outlier in terms of the new opportunities posed by the “revolution” in both the altered state of corruption combined with government and civil society attention paid to the new entrepreneurial landscape.

Late Development, Underdevelopment, and Uneven Development in MENA Entrepreneurship and Innovation

While the MENA region was once a bastion for innovation and advancements in development and scientific knowledge, that is plainly no longer the case. A 2005 study of 17 MENA Arab countries found that their combined output on scientific research was smaller than the output of Harvard University alone. (Wildson, 2007). Hasan and Kobeissi (2012) note that the 2009 Arab Knowledge Report’s (AKR) findings indicate that the Arab world contributes to 1.1 % of global scientific publications and spends one one-hundredth of what Finland spends on dollars per person in scientific research. Arab countries spend on average 0.2 % of GDP on scientific programs (the global average is 1.7 %). “While the lack of spending might be justified in some poor Arab countries like Yemen,” the authors find, “two Arab countries that ranked among the lowest investors in research as a percentage of GDP were the oil-rich countries of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait” (p. 457). While the MENA region is a leading innovator in desalination technologies, camel reproduction, and falconry research (Wildson, 2007), Arab Middle Eastern and North African states are far behind the revered position they once held relative to the rest of the world.

There are a number of ways of characterizing this phenomenon. In the 1960s, the term ‘late development’ arose to characterize those states that had not yet ‘attained’ modernization. It implicated a binary between ‘advanced’ nations, or ‘pioneers,’ and ‘backward,’ ‘late developing’ nations while also resisting modernization theory’s insistence on set and structured phases of development. The distinction thus called upon industrialization as the driving force behind development, albeit acknowledging that timing and sequencing matter. The so-called ‘backward’ nation is paradoxically in an advantageous position insofar as it has the ability to ‘leapfrog’ forward, skipping the steps in research and development that its more ‘advanced’ counterparts had to go through (Gerschenkron, 1962).

Five decades prior, Trotsky proposed that in borrowing technologies and ideas from ‘advanced’ states in the later stages of the capitalist epoch, ‘backward’ states confronted a problem of underdevelopment as a result of both ‘too much and too little capitalism (De Smet 2016, p. 116), or what he called ‘uneven and combined development’ (UCD). Accordingly, unevenness is the most fundamental axiom of historical development that applies to the tempo as well as the spaces of development across the globe and within and between different regions and states. The interaction of these differently developing social temporalities produces multiple, layered, and intrinsically unique patterns: “Development is, then, ineluctably multilinear, polycentric, and co-constitutive by virtue of its very interconnectedness” (Anievas 2014:43). Combination, or “the ways in which the internal relations of any given society are determined by their interactive relations with other developmentally differentiated societies,” is the byproduct of unevenness (Anievas and Nisancioglu 2015:45). The historical manifestation of unevenness and its production of combination explains the uniqueness of a society’s external/internal compulsion to develop, or the ‘whip of necessity.’ It also accounts for the privileged position ‘backward’ states potentially confront in their ability to learn from more ‘advanced’ states in order to ‘leap forward.’ Finally, it acknowledges the social relations that result within late developing states as a result of these processes (Anievas 2014:41; Rolf 2015).

Applying this schema to the MENA region, we might note that though all states of the region went through late and uneven development, they did not necessarily do so homogenously (indeed, this is the very point behind UCD). By the late nineteenth century, the French and British were supplanting Ottoman might on the south Mediterranean shores. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, Ottoman pressure on Europe produced and engendered the kind of merchant activity, regional competition, and internationalization that led to the capital accumulation that Britain, and later the rest of western Europe, needed to transmute from feudal social relations to those borne of the ‘logic of capital’ (Nisancioglu 2014). Yet having surpassed the Ottomans militarily and technologically, the Ottoman provinces variously experienced the ‘whip of external necessity’ that in all cases drove them to modernize their militaries and expand their state apparatuses lest European economic pressure result in direct occupation (Nisancioglu 2014). Thus, Ottoman advances drove forward European dominance, and later, colonization. The result was a giant leap forward for the so-called ‘West,’ and thence also the leadership position that Western firms and industries have taken in R&D, innovation, and entrepreneurial advantage.

Into the independence period, Arab nationalist leaders drew upon Arab nationalism, anti-imperialism, and later parochial anti-Islamist discourses to distract from the realities of class conflict. A “patriotic bourgeoisie” supported by Egypt’s Nasser and Tunisia’s Bourguiba alike promoted the national struggle for liberation from imperial power as a top priority while at the same time embedding their economies within those of the central axis of the Cold War powers. Arab nationalist leaders thus helped to consolidate, rather than vitiate, the formation of a domestic linkage to international networks of global capital. Using the Cold War rivalry to “square the contradictions stemming from its pro-capital orientation and its apparent confrontations with imperialism,” the region’s dictators deflected attention from class struggle with appeals to maintaining “national unity” (Hanieh 2013, p. 25). The combination of a quasi-socialist-cum-capitalist orientation meant the adoption of decades of confused and often incoherent economic policies that stymied overall economic growth and the opportunity to ‘leap frog’ over Western states with respect to industry and innovative technologies.

Late development has had several consequences on the region as a whole. The first among them with respect to entrepreneurship is to impact the capability of the region’s business sector to drive forward genuine innovation. The MENA region as a whole is still in an imitative phase of development and has yet to penetrate genuine innovation the kind of which leads to a transcendence from the immanence of underdevelopment. This is especially so for Egypt and Tunisia given that the UAE, as a rentier state, may draw upon vast oil reserves in order to siphon capital into entrepreneurial ventures, and perhaps soon innovation. But it also meant deeply entrenched forms of uneven development both throughout the region between states (rentier states versus non-rentier states) whose political strings were pulled by Western and foreign powers, as well as uneven development within the states of the MENA region. These legacies have lasting effects on the quality of governance and the relations between the region’s people and politics.

Comparing the UAE, Egypt, and Tunisia: Entrepreneurship Without Innovation?

Before proceeding with an analysis of these three cases, it is worthwhile to consider how one might circumscribe what constitutes “innovation.” According to Horth and Buchner (2014):

Innovation in the workplace refers to the way organizations are structured, that is: the way in which they manage their human resources; the manner in which decision-making within the organization is centralized or decentralized; and the way relations between the consumers and the company is organized. In addition, innovation is a reciprocal process based on continuous feedback from the customer, learning, training and improvement. Carried out properly, innovation has the effect of changing the organization workplace, a country and the world (in Mazouz et. al. 2019, p. 1).

Mazouz (2019) and his collaborators further define innovation as: ‘A new method, idea, or device; the introduction of new processes into a system; the development of new corporate processes and/or structures; and a new product, or a new invention (p. 2). Based on both internal (knowledge, attitude, and imagination) and external (culture, habitat, and resource) variables in their model corresponding to the human resources and the external environment, respectively, the authors find that “MENA organizations rarely provide enough time and they fail to spell out what exactly is expected. This suggests that the organizational leadership has not yet adopted a clear leadership style that facilitates the development of fruitful innovative ideas” (p. 10). Where innovation exists, it is largely imitative rather than radical (Nuruzzaman, Singh, and Pattnaik 2018, emphasis added). Much of this, as suggested below, is attributed to the lack of priority placed on education, available investment, and intellectual protection rights (IPR). As one study put it, “[a]lthough MENA countries have started to implement various initiatives to promote innovations, so far their actions have primarily focused on the “hardware” aspects, such as building infrastructure and investing in state of the art research institutions and educational facilities. They have not paid as much attention to the “software” aspects associated with reforming and protecting intellectual property” (Hasan and Kobeissi 2012, p. 477). Suffice it to say, then that genuine innovation requires capital (whether private or public) in addition to sound legal and bureaucratic policies and an insistence on the kind of education that spurns creative thinking.

The states across the region demonstrate different qualities and characteristics in these regards. Despite the general observation of late development, the history and empirics of the MENA region reveal a commonly observed distinction between, on the one hand, oil-rich, or “rentier” states of the Gulf that have capital, and middle-income countries like Tunisia and Egypt, on the other, which largely do not. While Egypt and Tunisia both experimented with quasi-socialist policies in the 1950s and 1960s, both turned towards a liberalization, or infitah, into the 1970s and 1980s whose integration into the global capitalist system following failed import substitution industrialization boded poorly for their positionality as peripheral states. The adoption of IMF and World Bank-backed reforms are still keenly felt in the post-“Arab Spring” period (Hanieh, 2015).

On the other hand, the Gulf states indeed leaped forward economically and technologically. However, oil was a double-edged sword. The social contract in the Gulf resembled ‘no taxation, but no representation’ wherein the sheikhs effectively bought off their people through the rents gained from oil. For Egypt and Tunisia, human development made leaps in overall indicators, but not so much relative to the kind of development early developing, Western states. Nonetheless, as is demonstrated below, the UAE is much closer to an innovation phase as a result of its rentier status and its ability to raise the capital necessary for radical rather than imitative forms of innovation. Much of this has to do with the resource available—both human and otherwise. If we examine the business climate across these cases, we see marked improvements in the UAE as a result of government initiative in efficiencies and reforms that, in turn, have attracted a vibrant yet nascent business angel community. Egypt and Tunisia, however, have remained fairly constant overall, though local context matters: both show signs of hope through private sector (Egypt and Tunisia) and civil society (Tunisia) initiative, input, and involvement.

Doing Business: Egypt

As early as 2011, Egypt reduced costs for new businesses and made trade easier through electronic innovations for import/export reports. In 2014, it became more costly for Egyptian companies when the corporate income tax rate was raised, but one year later minority investor protections were eased through additional requirements being levied upon larger companies with more severe requirements for disclosing transactions to the stock exchange. This was compounded, in 2016, by barring subsidiaries from acquiring shares issued by parent companies. And in 2017 and 2018, shareholder rights in major companies were buttressed by imposing a cap on foreign exchange deposits and withdrawals for imports. The process of starting a business was streamlined by “merging procedures at the one-stop shop by introducing a follow-up unit in charge of liaising with the tax and labor authority on behalf of the company.” However, property registration became more difficult when the costs of verifying and ratifying sales contracts were imposed.

This year, starting a business was made even easier by removing requirements to get a bank certificate, and access to credit was improved through the “granting a nonpossessory security right in a single category of movable assets without requiring a specific description of the collateral. Secured creditors are now given absolute priority over other claims, such as labor and tax, both outside and within bankruptcy proceedings.” Increased corporate transparency and extending value added tax cash refunds to manufacturers seeking capital transparency helped small businesses, and Egypt made a big move towards resolving insolvency by permitting debtors to begin a reorganization process and granting creditors greater say in the process.

Doing Business: Tunisia

In the post-uprising period, paying taxes was made more efficient in Tunisia through the use of an electronic system for corporate income and value-added tax. The electronic data interchange system for imports and exports expediated the process of import documents, though the cost of company registration increased in 2014. Trade became more difficult due to inadequate terminal space and poor port infrastructure. Though by 2016 the corporate income tax rate was reduced, and border compliance time of the state-owned port handling company increased efficiency. Tunisia also invested in the infrastructure of its Rades port. By 2017, credit reporting was made easier through the distribution of historical credit information through a major telecommunications company. Yet the tax regime required new corporate income tax contributions. This year, combining registration made starting a business easier, and properly registration was too by increasing the transparency of the cadastar. Minority investors protections were strengthened by “improving disclosure requirements of related-party transactions to the public and by requiring disclosure of directorships and primary employment.” And the corporate income tax contribution introduced in 2016 was not extended, thus making paying taxes a lot less burdensome.

Doing Business: UAE

The UAE has been quite exemplary over the past five years. Starting in 2015, property registration has been made less complicated through the introduction of new service centers and instituting a standard contract for property transactions. Getting credit was also streamlined through the credit bureau with the exchange of credit information through a utility and making the property registry more transparent.

Access to electricity was improved annually by, first reducing the time required to provide a connection cost estimate; implementing a new program with strict deadlines for reviewing applications; ensuring timely inspections and meter installations; providing compensation for power outages; and reducing electricity costs. Minority investor protections also made leaps and bounds since 2015 through more requirements for conflicts of interest and the appointment of auditors for unfair transactions. Upon obtaining 50% or more of the capital of a company, a purchase offer to all shareholders was required, and subsidiaries were barred from acquiring shares in parent companies. Control structures were also made more transparent.

Judicial proceedings and “Smart Petitions” that allow litigants to file and track motions online were integral to enforcing contracts, and the Ministry of Human Resources and General Pensions and Social Security Authority played a greater role in streamlining notarization and merging registration. Finally, providing credit scores to banks made starting a business much easier overall.

Source: “Doing Business 2019,” The World Bank, data available at doingbusiness.org

Local Contexts Matter: Examining the UAE, Egypt, and Tunisia’s Government-Civil Society-Private Sector Nexuses

The relationship between accountable governance, private capital, and a vibrant civil society is often taken as the hallmark of a healthy state-society relationship. Of the three states under study, only Tunisia can be said to be on a democratic transition (to say the least). In what follows, we do not seek to compare indicators across cases as in the analysis above, but rather to point out the local context and how it matters in each case. These are by no means exhaustive advancements, but instead represent hopeful achievements that lend themselves to ready analysis.

The UAE and “Angel Investors”

As explained above, the UAE has undergone quite drastic government-led reforms over the last ten years. Complimenting this shift, private and family firms have gravitated to the UAE, making it “the regional hub for entrepreneurship” (Henyon 2016, p. 32). However, civil society groups are largely out of the sphere of influence in driving forward entrepreneurship and innovation. Nonetheless, the UAE holds promise as an attractive area for international investment.

Business angels are new to the MENA region. Inroads began in 2005 but only started taking shape in 2008 (see below). Unlike institutional venture capitalists, business angels consist of private individuals who invest their own money, thus also incurring significant risk. They are also comparatively less experienced and often less formally educated in investing in new firms. Oftentimes, the business environment in which they operate also leaves angels less time for due diligence (Avdeitchikova, Landstrom, and Mansson, 2008).

Of the first eight Angel Investor Groups to open across the MENA region, four were established in the UAE: Envestors (2008), VentureSouq (2013), Women’s Angel Investor Network (WAIN) (2013), and WOMENA (2014). Ramesh Jagannathan, Vice Provost for Innovation and Entrepreneurship and Managing Director of StartAD, the innovation and entrepreneurship platform at NYU Abu Dhabi, notes that they “offer significant assistance in helping the start-ups cross the valley of debt.” With that said, there are still not enough angel investors. Najla Al Midfa, GM of Sheraa, remarks: “If you look at the US there are 400 of these angel groups and there are 300,000 angel investors. Over here there is of course VentureSouq, Wain, Womena – there are a few groups doing a really good job, but we need more of them” (Duncan, 2017).

Perhaps the largest problem facing angels in the MENA region are the lack of learning resources. Henyon (2016, p. 198) analyzes the environment for angels thusly:

Government initiatives have attempted to create angel investment groups but without success in most cases. With the exception of WAIN, where members undergo learning modules on topics such as mentoring, due diligence, valuation and governance while simultaneously conducting the investment process (screening, evaluation, due diligence, negotiation and closing), most angel groups (formal and informal) are not offering an educational component to their members. One of the challenges faced by angel groups in the region has been convincing their members to go through angel education courses. Many investors view themselves as experienced investors without understanding the nuances of angel investing. In addition, without much experience to date, typical angel investment challenges such as exits have not been an issue for investors in the region. Tax liability in international jurisdictions is another area that is not well understood (e.g., Dubai consists largely of a free trade zone without income tax).

Therefore, while the UAE is at the fore of angel investing, there is considerable room for growth in both the quantity and quality of the angels themselves. This should not be considered a negative attribute, but instead should instead be seen as an opportunity given the general upward trend that the government and private sector are forging. Still, civil society is largely missing from this equation, and the involvement of this third component of the nexus could aid in providing the education and facilitation of networks much needed to new and existing angel investors.

Egypt: A New Government-Private Sector Partnership?

Government support for entrepreneurship in Egypt has risen since the “Arab Spring,” as noted above. A reduction in regulations and tax exemptions as well as the streamlining of the process for starting a business have had marked results. As have low-interest rates and easier access to loans. According to Ahmed Bagoumi, the Accelerator Program Manager of AUC Venture Labs, there is direct connection between recent government support and the economic and political challenges posed by the uprisings of 2011–2013:

In 2011, when the revolution happened in Egypt, everything…was shut down, yet the banks didn’t close. Why didn’t the banks close? Because there were SMEs everywhere…I’m talking restaurants, the local grocery store, that kept the money circulating... So the government and the officials they believe that entrepreneurship is one of the reasons that drive growth in a country and that in moments of crisis entrepreneurship saved the economy from going bust. It actually started over the past 5-6 years that they’ve started to help entrepreneurs and be flexible with the regulation.

Both the government and private sector have contributed to notable initiatives. For example, the Ministry of Investment started an accelerator for early stage start-ups called Feps (Faculty of Economics & Political Science at Cairo University). Start Egypt is another such government-led initiative. Gaining financial support from the British Embassy in Cairo in partnership with the International Finance Corporation and Flat6Laps, Startup Egypt began offering a pool of 47 million EGP in grants in November 2017. Some of the notable recipiences are Tajdeed (Aswan), which is working on a Solar Cleaner Robot to clean solar cells; Opuntia (Minya), which endeavours to be the first company to extract seed oil from the prickly pear seeds for health, cosmeceutical, and pharmaceutical purposes; IOP (Tanta), which seeks to collect data from soil to measure water level and humidity and transmit it to a mobile app; and Konsolto (Cairo), which streamlines patient health care by consolidating medical reports from all systems across healthcare facilities (British Embassy Cairo, 2018).

Both private and public investment is heavily represented at the annual Riseup Summit in Cairo. It was attended by over 5000 people from 41 countries in 2017 in which 250 start-ups were offered the opportunity to meet with over 200 investors. Workshops and panels were held by over 250 speakers across the Greek Campus and American University of Cairo. Spawned from this initiative came Riseup Week just this year, an initiative of four governorates (Assiut, Sohag, El-Minya and Qena) in Upper Egypt, 500 kilometres south of Cairo in Egypt’s otherwise marginalized south. Participants vie to win up to 30,000 EGP in funding. The event attracted one of the Middle East’s first angel network, Cairo Angels (est. 2011), as well as Nile Angels, a network of angel investors established in Upper Egypt (Nabil, 2019). Thus, in Egypt marked changes are on the map that tailor to both Egypt’s business center in Cairo as well as its interior. This focus on developing the underdeveloped areas is especially important for ensuring a counterweight to the uneven patterns of development endemic to the region’s non-coastal areas and offers promise to those with innovative ideas but without the means to access resources otherwise.

Tunisia: A Revolutionary Exception?

The achievements that have arisen from the uprisings or “revolution” in Tunisia—substantive freedoms of speech and assembly and a nascent electoral democratic experiment (both municipally and nationally)—are an exception in their capacity to influence the overall business environment. There, new possibilities created by an opening of civil society led by a new class of tech-savvy youth (Gordner, 2015) has been accompanied by a “democratization of corruption” (Yerkes and Muasher, 2017) in which the Ben Ali mafia state’s dismantling also precipitated changes in the processes of starting, participating in, and doing, business. The government is sorely lagging behind both the private sector and civil society, however, with analysts lamenting the lack of agency and political will on the government’s part.

The Startup Act is an indication of the power of civil society and as such is hailed as “groundbreaking” (Sold, 2018). On April 2, 2017, the Tunisian parliament passed the law as part of its “Digital Tunisia 2020” strategy. The act was intended to make it easier for start-ups to come to fruition. The strategy itself encompasses 64 projects to be implemented as public-private partnerships. It was the culmination of the work of civil society pushing through parliamentary lag typical of the post-uprising government(s). Alongside Noomane Fehri, the then Minister of Technology, 70 entrepreneurs, investors, and accelerators met in Ghazzali, and then in Cogite, to put together a proposal on paper as a draft law (Sold, 2018). As Houssem Aoudi recalled:

We lobbied around executive power, the Prime Minister, Minister of IT, and MPs. It was widely embraced. What ended up happening was that people came together because they believed in it. We had to fight for it, and they removed half of it. At the end of the day even the central bank said ‘don’t touch it and pass it. This was the first time when civil society came together with the government and we built something. This was the first time also that we gave breaks to the entrepreneurs, including access to foreign currency.”

(Interview with the author)

The new political conditions also meant that the space is and will be created for corruption and bureaucratic obstacles to be (re-)interlinked in interesting ways that pose an opportunity for Tunisia to overcome its legacies of authoritarianism. As Goeduys-Degelin, M., Mohnen, P., and Taha, T. (2016) note, where bureaucratic obstacles exist, corruption can be a mechanism to overcome hurdles and provide information shortcuts. However, corruption also “directly hinders innovation by reducing the overall trust in the market and the national innovation system and by channelling investments away from productive projects. Both effects depress the likelihood that firms innovate” (p. 21). Thus the “revolution” in Tunisia poses both new sets of obstacles, but it also engenders potential new beginnings. Unfortunately, however, confidence in the government remains low both in fighting corruption as well as supporting civil society and the private sector. As Slah Kooli, Founder and Managing Director of the Tunisian American Search Fund (TASF), opines:

The government is still out of step. The start-up act is the civil society and the private sector that pushed the project forward. The role of the government is to set the conditions and therefore to anticipate the strategic axes. The government’s power of anticipation is very weak. The way the Tunisian state operates today means that even a large company cannot get away with it because of the administrative straitjacket, the lack of regulation and excessive paperwork. I am very adamant about this, I don’t believe it and I will never believe it.

Despite government reforms, Kooli continues, the authorities have not yet put in place laws and accounting strategies to move SMEs forward. However, for now, innovation is happening apace:

There is a lot of exclusive innovation, there are quite a few that are also inspired by what is being done abroad, but that is not a problem. Replication can generate specific innovation. There’s nothing to worry about. Great painters copied before they were great painters. The essential thing is the entrepreneurial mindset that must be developed. Duplicating and adapting to the local market can be interesting. Tunisia’s smallness is unique, which means that instead of having a globalizing idea, it must be adapted to the country.

Thus, while civil society and the private sector are working together in Tunisia to move the yardstick of growth and imitative innovation, the sense is that the government is still not in lock step with the kinds of reforms that practitioners believe can make an impactful contribution.

Conclusion: MENA Entrepreneurialism Towards Innovation

As of now, the UAE is leading the charge in terms of building capital for potential innovation through the fostering of business angels and government reforms making doing business easier and more efficient. While the Egyptian government—perhaps out of necessity—realizes the need for greater support for entrepreneurialism, civil society is still very much left out of this equation. Tunisia’s civil society, on the other hand, was a driving force behind the Startup Act, and coupled with a shift in the types of corruption endemic to the country’s new political scene, there could be marked changes on the horizon.

Still, the region’s entrepreneurs at large are in nascent phases of development. Many “survival” entrepreneurs still struggle to transcend the danger zone in which they might be capable of taking risks. Until the region’s entrepreneurial class can climb from imitation to innovation, however, the mechanisms and consequences of late development will obtain. Greater integration of the region’s political and economic elite in a concerted effort to traverse this regional problem is required given the integration of the region’s individual nation-states into a system of global capitalism that is still in many ways predatory, and where neo-colonialism in the form of dependency exists. However, the future is bright for the MENA region, no less because of (or despite) the “Arab Spring” and the challenges and opportunities that it poses to our communities.

Houssem Aoudi is a noted Tunisian entrepreneur, the founder of Afkar Incubator, Wasabi, and TEDxCarthage, and the cofounder of Cogite Coworking Space. He served as the director of the Media Center for the 2014 Tunisian parliamentary and presidential elections and was a Draper Hills Fellow at Stanford’s Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law.