- International Affairs

- US Foreign Policy

- US

- Security & Defense

- Terrorism

- Law & Policy

- US Defense

- Energy & Environment

- History

The following is our Islamic response back to your . . . accusations. First, “the conspiracy accusation”: this is a very laughable accusation. Were you expecting us to inform you about our secret attack plans? . . . We were exercising caution and secrecy in our war against you. . . . As the prophet has stated, “War is to deceive.”

—Khalid Sheik Muhammad, responding to charges of terrorism

Today’s terrorists may be skilled at high technology, but they still take advantage of old-fashioned, low-tech methods of evading and attacking high-tech adversaries. In an age-old pattern that remains true in the cyber age, forces that are unable or unwilling to confront technological superiority in battle seek out simple but hard-to-detect means of subverting their advanced foe. Countering these low-tech elements of the terrorist threat requires special strategies and an understanding of the human networks that employ terror.

Recent news stories about detention and interrogation have offered a glimpse into the inescapable human element in intelligence work. Free societies such as the United States try to constrain intelligence and counterterrorism methods to uphold moral, legal, and political commitments. On the other hand, terror suspects may benefit from these attempts. They are trained to resist interrogation if captured and to claim abuse. Even if intelligence is collected from them, the information may be restricted by the government’s need to protect methods and sources as well as to guard against internal security risks and disclosures damaging to national security. If authorities do release details of intelligence techniques, including interrogations, terrorists gain invaluable insights to help them plot, conceal, and train for future operations.

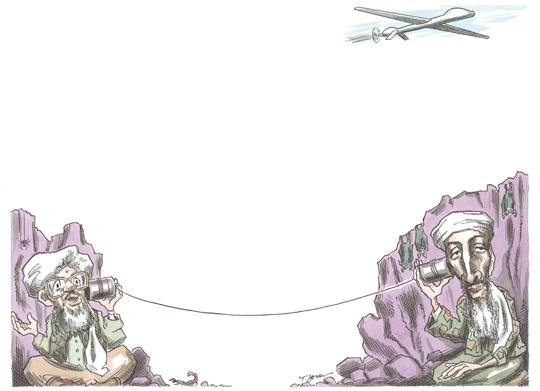

How can terrorist-hunters gain the upper hand? Technology, of course, has become increasingly important in the cat-and-mouse game of intelligence. A terrorist nearly anywhere in the world might access Internet and satellite communications, slipping into a vast electronic web of billions of messages and users. His pursuers, meanwhile, have become increasingly adept at intercepting and analyzing massive amounts of that worldwide chatter. Uncovering specific threats in large digital data sets remains a challenge, however; there might be no evidence of a threat, not for lack of searching but because of the way some adversaries employ low-tech defenses.

Covert tactics, unlike specific technologies, endure across subversive groups and over the years. Confronted by unmatched U.S. resource superiority, terrorists, insurgents, and spies rely on these established methods to conceal their human networks. They leverage social allegiances and physical interactions that leave no ready electronic traces. Their toolbox includes disguises, face-to-face and courier communications, cash or barter or unrecorded transactions, and weapons that are basic, even crude (box cutters, homemade explosive devices, and suicide bombs). Such low-tech methods are robust and self-reliant, easy to use and to conceal, yet difficult to trace. Nonetheless, terrorists may be betrayed by their distinctive choices of which techniques to use under certain circumstances. Such clues about the nature of their mission can give warning of an attack—if recognized.

Covert organizations use various technologies for different purposes. Routine activities may be performed openly. Communications content may be hidden by encryption—or by innocuous-sounding code words that are impermeable without inside knowledge. Research into covert organizations finds that analyzing the way they communicate and attempt to conceal their information helps to flesh out organizational dynamics and clandestine plots. Activity consistent with target surveillance, for instance, may signal hostile intent. Certain patterns of clandestine meetings, couriers, coded letters, and other such physical interactions may consistently precede major attacks. At the same time, intercepted electronic chatter may be fruitless because individuals chatting online may not be involved in a plot that is in the works. Traces of low-tech clandestine craft need to fit into a rich communications template that fuses multiple intelligence sources—everything from electronic surveillance to human agents—to better detect the signals of an impending attack.

Discovering actionable insights—those proverbial needles in the towering haystack of intercepted information of uncertain value—requires a systematic understanding of organizational dynamics. Once a picture of the adversary’s technology use begins to come into focus, the mere fact that the surveillance subjects are interacting—and their choices of how to interact— may indicate attack precursors under well-designed models of clandestine craft. The advantage remains even when the message content itself is unavailable or unreadable.

PROBING THE HUMAN NETWORKS

Communications technologies trace human network interactions. Networks serve typically to enhance communications, but covert groups with hostile opponents face different constraints. They must prioritize security and secrets, and thus their networks benefit not from expanding but from limiting connections and communications. This complicates their work but enhances their survival. Low-tech techniques that leave no ready traces serve this purpose, whereas cyber infrastructures introduce a risk. What follows are examples of how these decisions work in practice.

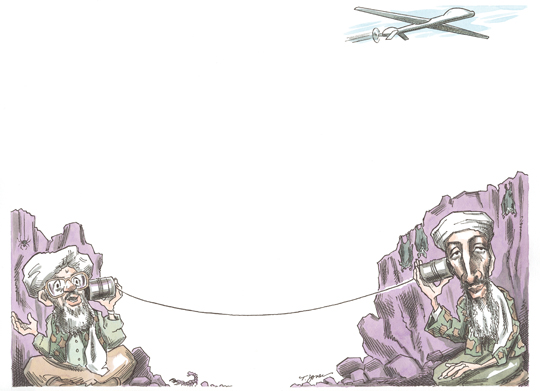

Why have Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri been so difficult to find despite sophisticated U.S. tracking approaches and a hefty reward offered for information leading to their capture? Their communications choices make up part of the answer. They stopped using the satellite phones that would reveal their locations. Human couriers, coupled with the protections of co-religionists and tribal allies, help curb information about their whereabouts and activities. Al- Qaeda also may have learned from others’ mistakes. For instance, a Soviet general turned Chechen separatist leader, Dzhokhar Dudayev, was located by intercepting his satellite-phone conversation and killed by laser-guided missiles sent to that spot. High-tech devices are traceable through the electronic infrastructure that supports them, and this traceability endangers terrorist organizations. Low-tech approaches offer sanctuary for human networks and are difficult to penetrate. Such approaches helped cloak the preparations for the September 11 attacks, for instance.

Why are suicide bombers such a threat? Advanced technology can help remotely disable guided missiles and help jam electronically activated bombs, but humans offer naturally guided weapons that are adaptive and disguisable on site. Suicide bombers armed with makeshift devices, such as the improvised explosives devices (IEDs) used effectively in Iraq and Afghanistan, are especially secure from the perspective of a terrorist organization. (Some devices come from nations that outdo the terrorists in weaponry skills, but the effective use of the weapon still relies on the human element.) In a human network with compartmentalized operations, separate units make the devices, survey the targets, and handle the logistics. Before an attack, a sophisticated terrorist organization provides a bomber only minimal information and only when necessary. This limits the network’s exposure if the bomber fails, defects, or is captured. After the attack, the bomber’s death erases the operational connections, and the organization survives to bomb another day.

Such asymmetric threats have plagued the ongoing conflicts against Islamist terrorists, but they are far from new. They have been used at many different times and in support of different causes. The use of explosives-filled truck bombs driven by suicide bombers, for example, includes Al- Qaeda’s 1998 bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania as well as the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine barracks in Beirut linked to Hezbollah, Iran, and the Palestine Liberation Organization. Prominent examples of other types of IED bombings include the 1991 suicide-bomber assassination of India’s prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi; numerous Palestinian attacks against Israel; and, in the wake of 9/11, Al-Qaeda’s 2001 assassination of Afghanistan’s Northern Alliance leader, Ahmad Shah Massoud, a U.S. ally. Likewise, civilian aircraft hijackings and attacks, among other tactics, date back at least to the Cold War.

Abu Ibrahim offers one case study in both the long-term use of such techniques and the ability of a terrorist operator to elude pursuers. Now sought in Syria after he disappeared from Iraq in 2004, Abu Ibrahim, seventy- three, was suspected of supporting the insurgency in Mosul, Iraq. He is reported to have earlier trained with the KGB, supplied devices for airline bombings since the 1980s, worked with Black September and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, started his own “15 May” terrorist group, designed suitcase-concealed bombs for attacking aircraft and other such civilian targets, and lived in Baghdad under the protection of Saddam Hussein. Despite pursuit by the CIA and the FBI, he has continued to evade detection and to perpetuate terrorist craft.

The Haqqani network, operating out of the dangerous Waziristan region that bridges Afghanistan and Pakistan, exemplifies another current threat whose militant activities have continued over the decades and in numerous conflicts. The Haqqani family has run extremist madrassas, commanded Taliban forces, and collaborated with Osama bin Laden. The family’s patriarch, Jaleluddin Haqqani, earlier served in the Taliban government. The Haqqanis have led insurgency attacks and organized suicidebombings against U.S. and coalition forces. Reports indicate that Haqqani elements also fought against the Soviet military invasion of Afghanistan years ago and were supported by the United States in that struggle.

Such examples are many. What they share is an approach based on loyal human networks and low-tech techniques. For these networks, traceable technologies only heighten the risks.

MULTIPLE WAYS OF UNDERSTANDING

Intelligence remains a human effort, and so does the terrorism it seeks to thwart. Tracking the tools that perpetrators choose and how they use them sheds light on the activity dynamics. Groups and technologies evolve, creating new ways to assault defenses. But the old-fashioned means must not be underestimated.

Electronic chatter alone may fall short on predictive power when key terrorist organizers stay offline. Authorities too often issue general terrorist warnings, based on unspecific chatter, that are not followed by actual attacks. These false alarms risk desensitizing people to the terrorist threat, making legitimate security measures more difficult to implement. Low-tech data alone also may be insufficient, as it is difficult to obtain and verify. All available sources are needed to detect signals, estimate the uncertainties, and, if necessary, take action.

Along with multiple sources of intelligence collection, multiple sources of knowledge can offer guidance into what to seek. Historical accounts and archival records contain clues for recognizing secret craft that modern adversaries still employ. Records that document various clandestine operations— such as those collected in the Hoover Archives and elsewhere—help analysts grasp the enduring principles behind covert networks and model the conditions under which different technologies succeed.