- Law & Policy

P

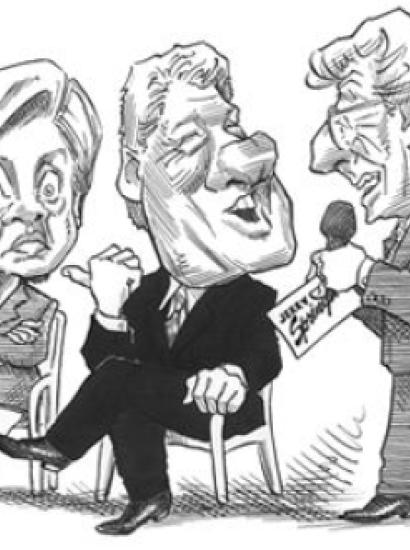

rivacy is like oxygen. We really appreciate it only when it is gone. The death of Princess Diana, the political convulsions over Bill Clinton’s sex life, and celebrity complaints about the predatory media give the issue prominence. But it is not the violations of the famous that make the battle over privacy the preeminent issue of the Information Age. It is the erosion of privacy in our everyday lives.

Snoops have always been with us. From time immemorial, gossips, nags, governments, and journalists have tried to listen in on our conversations, follow our comings and goings, and hunt for grist for their endlessly turning mills. What’s new, however, is the tools they now have at hand to watch, listen, and record. Technology makes the fears of the paranoiac of the past seem Pollyannaish compared with the realities of the present and the prospects for the future. If it remains true that everyone is famous for at least 15 minutes, it is also true that the average citizen now experiences the loss of privacy once reserved for the famous and infamous.

Questions of privacy touch us in nearly every aspect of our lives—from our relationships with our doctors to our ability to communicate on the net to the intimacy of our personal relationships.

At the beginning of a new century, the challenge to privacy comes from many fronts:

-

Modern technology has made it possible to create vast new dossiers of extraordinary detail and specificity about our tastes, habits, and lives. Every time you apply for a job, subscribe to a magazine, call a mail-order catalog, use a credit card, dial a phone, seek credit, fly on an airplane, buy insurance, rent an apartment, drive a car, pay taxes, get married or divorced, sue someone, see a doctor, use a smart card, apply for government licenses or benefits, you become part of the data web, which has proven far more powerful than the paper trails of bygone years.

-

The Internet has rewritten the rules of private and public life, providing an illusion of privacy in a realm that actually is a fishbowl.

-

Even as the private sector develops new techniques for tracking us, new government databases, ranging from information about newly hired workers to airline passengers, threaten to create a seamless data web that blurs the lines between government surveillance and commercial marketing.

-

The National Research Council has warned that the medical records of millions of Americans are vulnerable to abuse, noting that “today there are no strong incentives to safeguard patient information because patients, industry groups, and government regulators aren’t demanding protection.” The federal government continues to move toward creating a single, universal medical identifier that will track every visit to a doctor’s office, every treatment, and every prescription for every patient from cradle to grave.

-

In politics the personal has become the political, shrinking the zone of privacy, making the lives of politicians—and the rest of us—fair game. The loss of privacy has, in effect, become a tax on involvement in public affairs.

-

Fueled by our penchant for therapy and sharing, Americans share their intimacies and dysfunctions with therapists, casual acquaintances, and national television audiences. The effect is numbing—does anything shock us anymore?

-

The hypercompetitive media continually revise their standards downward as the line between the tabloids and the mainstream press is erased. The Internet is rapidly breaking down whatever barriers between rumor and news may have survived.

-

Workplaces continue to be no-privacy zones, where employers read the e-mail of, listen to the phone calls of, electronically monitor, and videotape their employees. One survey found that nearly three-quarters of large corporations collect information about their workers beyond what employees voluntarily provide; more than two-thirds report hiring private investigators to check into the background of their workers; more than one-third use medical records to make decisions about employees.

-

Anxious to protect its own secrets, the government remains jealous of the ability of citizens to keep their own. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies want to deny the rest of us the ability to encode our own communications to prevent their easy interception or reading.

It is easy to see what is at stake.

The greatest barrier to the growth of commerce on the Internet is not technological. The net will realize its potential for hypergrowth only when it resolves concerns over the privacy and the security of information transmitted through cyberspace. Privacy may be worth uncounted billions of dollars.

Perhaps even more urgently, concerns over privacy threaten to erode many of the advances in medical science, including those involving genetic therapy. Fearful that certain information could damage their ability to obtain insurance or jobs, patients are already avoiding tests and even doctors altogether.

Already the political landscape is being laid waste by the assault on the private lives of public and private figures alike. At the heart of the cultural, political, and legal schism over the fate of President Bill Clinton was the question of privacy, an issue that threatens to spill over and poison public life as a whole.

But the greatest threats—obscured in debates over sexual McCarthyism, media intrusion, and technological snooping—go to the heart of our self-identity. Some commentators suggest that privacy is the essence of being human, but, in fact, it is quite possible to be human without privacy. It is more accurate to say that privacy is essential to being a free human being.

Balancing Acts

The truth is that as much as we deplore the erosion of privacy—and we can be quite eloquent on the subject—many of us accept the violations in the name of a wide range of equally attractive virtues and interests. To paraphrase Jane Austen, privacy is a value that everyone speaks well of but no one remembers to do anything about. No one disparages privacy to its face. We simply choose to emphasize the public’s right to know, national security, personal safety, convenience, economic opportunity, politics, ideology, or the pursuit of virtue. Privacy may be all well and good, but the economics of direct marketing is often far more compelling. The hypercompetitive environment of the new media makes reticence seem an unaffordable and archaic luxury, and, anyway, what are you trying to hide? Indeed attempts to protect privacy are frequently regarded with suspicion.

These days, privacy is whipsawed from both the left and the right. Unfortunately for privacy, this means a two-front war. If liberals seem anxious to intrude into private lives in the name of compassion, conservatives often act as if they want the state to be the arbiter of community and personal morality. Whereas the left has supported the proliferation of government-run social welfare databases, the right has championed the demands of law enforcement agencies that want a back door to our personal communications. Conservatives object to government intrusions such as a national ID but are reluctant to support any restrictions on the growth of massive private sector data dossiers, even though they increasingly blur the lines between government and private information gathering. The left has a proud tradition of defending civil liberties, but therapeutic liberalism has waxed eloquent over the notion that it takes a whole village to raise your children.

Exposing Ourselves

The political and ideological threats are dramatically magnified by the more general spirit of the age. We are not the first culture to revel in gossip, but our distinctive contribution is not gossip but exhibitionism. Having perfectly soundproof walls, we have become a society that cannot shut up. The classical belief that the unexamined life is not worth living has been replaced by our modern conviction that the unpublicized, unexposed life has no socially redeeming value.

Not only does the love that dare not speak its name now never shut up—no one else does either. The result is a society of way too much information.

Joyce Maynard seeks to claw her way up from mediocrity by exposing her relationship with the intensely private and reclusive J. D. Salinger. Dr. Laura’s ex-boyfriend sells nude pictures of the virtues maven for posting on the web. Dr. Jack Kevorkian and 60 Minutes team up for a televised episode of euthanasia. Even the most famous privacy victims, Princess Diana and Bill Clinton, found it necessary to share details about their most intimate affairs with worldwide audiences. Privacy is worse than irrelevant.

|

We have become a society of exhibitionists. The classical belief that the unexamined life is not worth living has been replaced by the modern conviction that the unpublicized, unexposed life has no socially redeeming value. |

Yet the culture of full disclosure does not seem likely to wither away. It has, however, established a cultural climate of disdain for privacy and distrust of those who avoid exposure or insist on keeping their private lives to themselves. That, in turn, influences the cultural, political, and legal climate for privacy.

But it is not the freakish or the abnormal that is most alarming: it is the routine, the habitual, the almost numbing regularity with which others intrude on our private lives. At times it may be possible to ignore the implications of all of this. We believe that we can chip away at others’ privacy but keep our own intact. All the while, we are changing the standards of what is private and what is public, shifting the lines depending on our moods, our politics, or the light. Perhaps the best example is how we feel about sex.

|

Most Americans have only the vaguest idea of how much of their lives is transparent or how vulnerable they are to the new technologies and instruments of surveillance and monitoring. |

Is sex our most private or our most public activity? Starting in the 1960s, the courts have carved out a special zone of constitutionally protected privacy for almost all matters sexual, from the reading of pornography to the right to procreate to contraception and even abortion. But if sex is private, one would not know it from going to the movies, reading the papers, or watching the typical prime-time sitcom. In modern culture, sex is as private as any other national pastime, and it gets higher ratings than baseball. Nor is this simply a matter of culture: sexual harassment law has turned some of the relations between men and women into matters of law and political debate.

We have found that the loss of privacy, like any once-released genie, is very, very difficult to put back into the bottle.

The Privacy Paradox

Having said all this, defenders of privacy need to confront several difficult questions: If there is a genuine concern for personal privacy, as public opinion polls consistently indicate, then why do so many people behave as if they do not care about their privacy? Why do people tell pollsters they are alarmed about the loss of privacy but then blithely give out their credit card numbers over the Internet? Or sign consent forms that allow sensitive medical information to be seen by dozens of eyes? Even granting the institutional power of the antiprivacy forces, why has the political support for privacy protections been so ineffectual?

First, most Americans have only the vaguest idea of how much of their lives is transparent or how vulnerable they are to the new technologies and instruments of surveillance and monitoring. But even among those who do have some idea that their privacy is in jeopardy, many feel powerless to do anything about it, perhaps seeing it as an inevitable by-product of the information age.

But there is another explanation as well. Privacy is not an absolute; like free speech, or any other right, it must be weighed in the balance against such values as freedom of information, free trade, national security, and the public’s need to know. Indeed, there are so many competing claims that privacy can hope to survive the balancing tests only if it is well established and well understood as a basic principle. But it is neither. Its legal status is confused, at best. And among the lost arts of our age is the ability to gracefully tell another, “It’s none of your business.” In part, that is because we too often forget why privacy matters.