- Security & Defense

- Determining America's Role in the World

For the first time, Israel is committed not only to the defeat of the enemy's forces but also to the annihilation of its regime. That is one reason the Gaza war proves to be a long war of attrition. It is the consequence of not only the Oct 7th catastrophe, and a years-long policy of appeasement but also the gradual derailment of Israel's defense strategy. What is needed now is a reform aimed at restoring IDF's decisive battlefield capabilities, without which we face the impossible dilemma of living with further hostilities building up on our borders or a Gaza-like war on a greater scale in Lebanon. As war is making its comeback to history everywhere, the West should take note of Israel’s endeavors.

In his book, The Culture of Military Innovation (Stanford 2010), Dima Adamsky refers to the Israeli strategic culture as one of tactical excellence and innovation on the one hand and theoretical incapacity on the other. Many of us, including Adamsky, himself, saw that culture as changing for the better. Unfortunately, the multi-front Gaza war exposed the inadequacies of that change - too little too late.

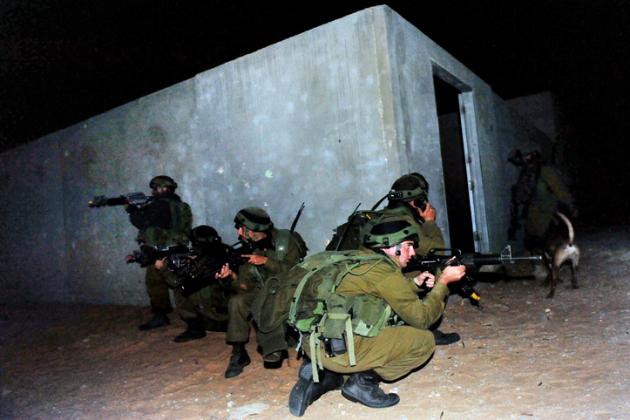

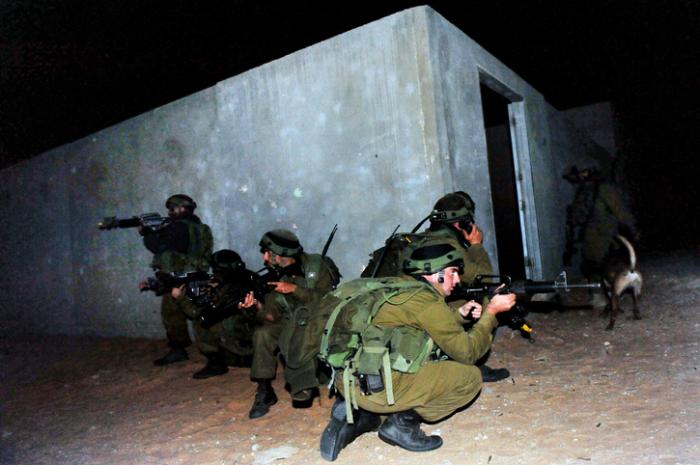

The war in Gaza is a showcase for the sharp contrast between IDF's superb performance in the offensive phase in Gaza, and the clear mismanagement of the war at the higher military and political levels.

While that gap is apparent for all observers to see, what is less obvious is the failings of Israel’s three-decades-long strategy which collided with the changing circumstances. Analyzing the war from that perspective does not relieve Israeli leadership today of the October 7th disaster, the protracted nature of the war, and the ongoing hostage crisis. However, It does enable a deeper look into our strategic position and hopefully provides for better learning and adaptation.

Israel's first total war

By "total war" I do not mean to say that Israel is engaged in a 20th-century style conflict between nations that involves the industrial base, cities, and population of both sides and the unlimited use of all weapons at hand. In fact, I cannot think of a more bizarre case where a nation, after experiencing an attack such as occurred on Oct 7 is fighting the enemy on one hand and seeing to the delivery of food, medicine, water, fuels, and even internet communication to the enemy's population on the other. Needless to say, Hamas's fighting force is the number one beneficiary of that flow of commodities.

What total war here refers to is the complete contrast between Israel's limited wars of the past and the present one. It is the first war in our history where the aim is not simply to remove the immediate military threat to Israel and end the fighting quickly, but rather it is a commitment to the annihilation of both the military force and the political regime of the enemy. Let it be clear: this is a just and necessary war. Nevertheless, it does drag Israel into a war of attrition that clearly overwhelms the capacity of the IDF and Israel to sustain military, civilian, and international efforts.

So the real question at hand is how Israel cornered itself in this dead-end situation.

The most apparent answers will be the failures that led directly to Oct 7 such as the lack of early warning, followed by the devastating collapse of the thinly deployed IDF forces on that day. On a strategic level, however, the question is how did we allow the build-up of the Hamas army on our border? Even the shameful policy of appeasement towards Hamas, a policy as old as Hamas's rule over Gaza (2007) does not provide a complete answer. If we are to learn anything beyond the political blame game that is tearing Israel apart, we should search even further.

Three disruptions put Israel's traditional defense strategy out of balance. Just as Adamsky described it, while the IDF was relatively quick to adapt tactically, the strategic flaws were overlooked and the more profound military change that was needed was delayed. That is a process that originated in the days of the Israeli-held security zone in south Lebanon in the 1990s.

David & Goliath

The most basic observation of Israeli strategy and doctrine in the 50's was the fact that we cannot change the nature of the conflict by force. We cannot defeat the Arab coalition in the way the Allies defeated Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. So the small state of Israel devised a modest strategy:

- We will only aim for a military, not a political defeat of our adversaries.

- To do that we will concentrate all resources and personnel in a short decisive war effort that will take the war to the other side to remove the immediate threat.

- We will make all efforts to avoid protracted warfare we cannot sustain.

Fast-forward to the 1990's and circumstances seemed to have profoundly changed. The Soviet Union had just fallen, further weakening its Arab clients, Egypt had withdrawn from the Arab coalition, and the IDF was one of the most modern militaries on the planet with cutting-edge targeting and airpower precision strike capabilities.

And yet, faced with guerrilla warfare in southern Lebanon, Israel's strategy was disrupted. Protecting our northern border from within southern Lebanon has led to prolonged warfare with new Lebanese factions. Moving the battle to the other side now proved more of a problem than a solution.

A new strategy was starting to emerge. Never to be officially put in words or on paper, its preferred principles were simple:

- Israel's advantage lies in airpower.

- Decisive battlefield maneuvering is impractical in the new context. Fortunately, it is also unnecessary.

- Israel is now the Goliath of the equation. Indeed, it is a regional power. We can and should engage in a war of attrition, rather than finding a way to remove the emerging threat.

- Guerillas are inherently less sensitive to airpower. So, Israel's strategy will be one of coercion, aimed at a "responsible state address" such as Lebanon or Syria, hosting or supporting them.

Gradually, three processes took place:

- Airpower coercion became the securing base for the strategic deconfliction strategy practiced with the withdrawal from Lebanon (2000) and disengagement from Gaza (2005).

- The IDF became a formidable targeting machine. Later other excellent tactical adaptations to the deteriorating situation, like air-defense systems, were achieved. Seen as a thing of the past, ground forces were largely left behind.

- Unaffected by the new strategic theory, the adversaries have grown from small guerrilla entities to full-scale militaries based directly on our borders. Rather than responding to Israel as a superpower, the other side simply enhanced its ability to inflict damage on our cities and disrupt peace on our borders.

By the early 2000's Israeli leadership talked about deterrence but was simultaneously deterred itself. The much-talked-of air campaign Israel has engaged in in Syria since 2012 only serves to highlight the lack of Israeli willingness to stop the entrenchment and armament of Hamas and Hezbollah in Gaza and Lebanon.

The big disruptions

Three major disruptions led to the derailment of Israel's traditional strategy:

- Control over foreign hostile populated areas, like South Lebanon or the Gaza Strip, has proven to drag Israel into undesired prolonged warfare.

- Rockets and missiles have proven to be the ultimate strategic equalizer working against Israel’s military superiority. Holding Israeli cities hostage, they have made it possible for the weaker side to deter Israel from decisive operations, allowing the unhindered build-up of forces by Lebanese Hezbollah and Palestinian Hamas. It also rendered the withdrawal strategy useless as the rockets were aimed and fired at Israeli civilians from deep within Lebanon and Gaza.

- As for Iran – we went to bed in the 90s with some small and isolated guerrillas on our borders. One day we woke up realizing these are the paws of a huge Iranian tiger. We were thinking of ourselves as a Goliath gradually degrading weaker adversaries, only to learn we are in a war of attrition with a giant via its proxies.

Therefore it turns out that our main disruption was not from our adversaries but from within. Short-sighted policy from most Israeli governments helped, but the roots of the deterioration lay in false optimistic assumptions that were not challenged sufficiently:

- Can airpower really sustain a strategy by itself?

- Can Israel sustain the strategic competition with Iran while conducting attrition warfare with its growing proxies on its borders?

Progressives and Orthodox

We have favored a false theoretical framework, never to become official and truly challenged, and the comfort of doing more and better of the same. We have made huge tactical improvements but failed to make more profound adjustments to our theories and capabilities. One can make that statement based on the IDF's concept of victory from 2020 when it was given official recognition. That concept was supposed to be a vital first step for a military modernization plan. The plan was aimed at the reconstruction of the traditional defense strategy with decisive victory on the battlefield at its focal point. A variety of capabilities and organizational changes were planned to target the enemy’s distant fire and trajectories by utilizing modernized ground forces as well as air assets.[1] Unfortunately, it turned out to be too little too late.

For too long the strategic environment and actual threats were rapidly changing for the worse. Israel's strategic and military thinking was stuck between two opposing schools of thought. The first school created a framework of false assumptions that allowed the comfort of kicking the can down the road. The concept of engineering our adversaries' intentions rather than preempting their capabilities failed. These schools of thought can be described as "strategic progressives", turning wishful thinking into a strategy. Reacting against that, the other school can be labeled "military orthodoxy", denying the change of circumstances altogether. It called for bigger ground forces and a more aggressive approach with the unpromising prospects of house-to-house fighting to clear the enemy from Lebanon. This was a twentieth-century attrition approach to deal with the twenty-first-century challenge of a dispersed enemy with long-range capability. Policymakers, from all sides of the political map, thought that cure was worse than the disease.

Conclusion

Cornered now into a long total war against the Hamas regime, Israel can hardly sustain the effort needed and has no good solutions for the simultaneous threat from Lebanon. In contrast to its self-image as a regional power, Israel re-discovered its basic limits. As successful, flourishing, and technologically advanced as we grew up to be, we are still only David. Israel is not capable of politically engineering our neighborhood, not even in the small Gaza Strip.

The failure is far from being tactical or local. Rather than adapting to a new set of military threats within the correct framework of Israeli defense strategy, we have insisted on living in a dream world where terror organizations have state-like responsibility and Israel is a regional power that cannot be beaten.

From the three disruptions mentioned, the tangible one we can militarily work with is the second – arms fire, missiles, and rockets. Defeat that, and there is no Iranian ring of fire nor an adversary capable of deterring Israel from preempting threats.

We can and should come up with an approach that does exactly that. That approach may be of great interest for the West as it is faced with similar military challenges. The Russian war over Ukraine has come to be a war of attrition dominated by long-range weapons. China's strategy relies on deterring a possible US response for an armed provocation as its ranged A2AD missiles are deployed and aimed at any approaching navy and air force assets. If we can contribute valid and substantial ideas and capabilities to change that for the better, it could also facilitate a fresh restart for Israel internationally.

Brigadier General (Ret.) Ortal is the author of The Battle Before the War (Modan and the Ministry of Defense 2022, Hebrew) which deals with change and the need for change in the IDF. He now teaches Defense Strategy at Reichman University, serves as a senior consultant for strategy and technology at the Israeli MOD, and is a senior fellow at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies.

[1] See "Turn on the lights, extinguish the fires", War on the Rocks, Jan 19, 2022, or "Fighting Fires with Data", Defining Ideas, Hoover 2023.