- Economics

Janet Yellen is set to become the first woman to head the Federal Reserve. The Senate Banking Committee approved her nomination by a 14 to 8 vote, with two Republicans in tow. As chair, Yellen is poised to follow the Federal Reserve’s 1977 “dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices.” In nominating Yellen, President Obama endorsed a “sound monetary policy to make sure that we keep inflation in check . . . [while] increasing employment and creating jobs.” Yellen in turn said her mission was “to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and a strong and stable financial system.” The global markets seemed to be buoyed by the news.

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

But dissident Republicans, led by Marco Rubio, have criticized her as “a lead architect of monetary policies that threaten the short and long-term prospects of strong economic growth and job creation.” Unfortunately, Rubio’s opposition to Yellen did not reject the dual mandate. It only attacked the current Fed policy of keeping interest rates close to zero by purchasing on average about $85 billion in bonds in order to stimulate the economy through Quantitative Easing (QE). Stiffer medicine is needed.

The Problem With the Dual Mandate

The fatal flaw of the conventional wisdom lies in its inability to explain how to trade off each objective against the other. When Yellen says her job is to “promote maximum employment,” she implicitly relegates any other objective to a subordinate position. In this context, the Fed’s traditional monetary role has to take a back seat to the rapid improvement of the employment market. To be sure, the Fed is free to take any step that advances both of these objectives simultaneously, so long as employment is raised to its maximum. But that case turns out to be trivial, because the same result holds even if the Fed’s duty was to maximize price stability. Whenever the two objectives are perfectly aligned, no trade-offs are needed, so that any supposed difference in policy objectives would not matter.

The rubber only hits the road when labor and monetary policies diverge. A sound monetary policy normally requires one to keep interest rates at about 2 percent over inflation. The constant pressure to create new jobs is said to require interest rates to be set far lower. So which is it? The only way to make the appropriate tradeoffs is to adopt some overarching measure of social utility or welfare that reduces both elements to a single variable. Thus if employment objectives were 40 percent of the problem and monetary objectives 60 percent, 50 percent more weight should be attached to the latter. Implementing these dual missions will therefore raise difficult empirical problems, but at least the conceptual barrier is overcome. Unfortunately, the Fed just ducks this issue, as it fumbles along.

The Fed’s Performance Report Card

In light of the conceptual muddle, let’s ask just how well the Federal Reserve has done with its dual mission over the past five years. The President, as is his habit, accentuates the positive by ticking off a list of supposed achievements. In his remarks on Yellen’s nomination, he said:

Over the past five years, America has fought its way back from the worst recession since the Great Depression. We passed historic reforms to prevent another crisis and to protect consumers. Over the past three and half years, our businesses have created 7.5 million new jobs. Our housing market is rebounding. Manufacturing is growing. The auto industry has come roaring back. And since I took office, we’ve cut the deficit in half.

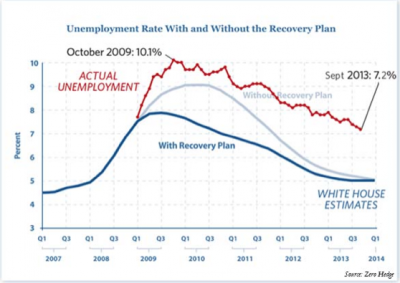

As a corrective to this beguiling tale, it is useful to note that inflation has been held at bay. But this simple graphic shows that the Fed’s stimulus plan has not lived up to expectations on the employment front.

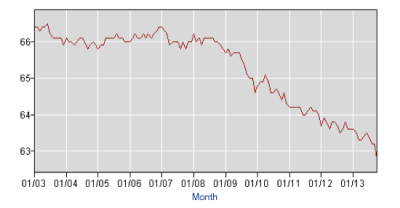

It doesn’t take a professional economist to see that the actual outcomes are worse than the administration’s predictions with and without the stimulus plan. Indeed the situation is in fact worse than this graph indicates because the current levels of unemployment do not take into account the changes in level of labor market participation. Notwithstanding the creation of those 7.5 million jobs, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that this critical statistic has fallen from about 66 percent in 2008 to about 63 percent today. Note the precipitous drop in labor market participation since Obama has taken office.

Labor Market Participation: 2003–2013

At this point, it is easy to do the math. Add the decline in labor market participation back to the present unemployment rate, and the total number of Americans out of work rises to about 10.2 percent, which is about where we stood in 2009. In the meantime, according to Census Bureau data, median income in the United States is now 6.6 percent lower than it was in 2000. There has been zero progress on the employment half of the Fed’s dual mission. Why?

Where the Fed Has Gone Wrong

To answer this question, it is useful to go back to another question. Why does anyone believe that the Fed can use monetary policy as a tool to reduce the level of unemployment? To fancy macroeconomists, monetary and fiscal policies can reduce unemployment. But just how is this supposed to work? The federal government decides to keep the interest rates low to make it easier for businesses to borrow. But that same policy causes major dislocations to people who are, for instance, trying to live on the diminished returns to their retirement funds. It is possible to expand the supply of goods, but only at the cost of lowering demand. At best the two policies look like a wash.

Indeed, the present reality is far from ideal for at least three reasons: the Fed’s monetary policies increase the administrative costs of running the system; they increase the levels of uncertainty for both sides of the market; and they subject the Fed to major political pressures that it is not well-equipped to deal with.

The same analysis applies if we look on the fiscal side at the stimulus program. On this issue, economists speak of the so-called multiplier effect, which in ordinary English means that every increase in expenditure generates (successively smaller) second, third, and subsequent rounds of expenditures, so that the overall increase in national income exceeds the initial expenditure. But it does not follow that government expenditures, even on infrastructure, outperform private ones. The real question is the trade-off at the margin, and the current spree has probably retarded growth by putting too much money in government hands, thus crowding out capital that could have been better deployed in private hands. Taken together, these two macro-policies have led to economic stagnation.

A Fresh Start on Labor Markets

The time has come to clear away the regulatory underbrush. Step one is for the Fed to scrap the employment mission. Step two is to pay some actual attention to how taxation and regulation dampen the performance of labor markets. At this point, there is no need to speculate about the indirect effects of the Fed’s misguided monetary policies. Rather, we can take a hard look at unwise government policies that gum up the labor markets.

Tackling this problem starts with a stripped down model of labor markets that highlights the essential features of their operation. The central driver in labor markets is gains from cooperation: the worker values his full package of benefits (of which wages are only a part) more than he does holding back his labor; the employer values the labor more than the cash (or other burdens of the labor market). Accordingly, the basic condition for a thriving labor market is, as Ronald Coase taught us, that the gains from trade must exceed the transaction costs needed to execute particular transactions.

At this point, the clear policy recommendation takes two forms. First, keep those transaction costs low for the formation of contracts. Second, allow parties the freedom to experiment with novel arrangements that maximize their gains. In general, these two prescriptions demand a system of competitive labor markets backed by strong government enforcement. In many instances, the preferred contract arrangement is the contract at will, which lets employees quit and employers fire at will.

For decades now, labor policy has attacked freedom of contract and employment at will arrangements. Today, employment contracts are governed by collective bargaining (which has a negative impact on nonunionized firms), the Fair Labor Standards Act (dealing with overtime and minimum wage regulations, family leave policies, healthcare mandates, social security, and Medicare taxes), and a whole lot more. The exact negative effect of these government constraints depends on both their substantive provisions and the level of government enforcement.

It should come as no surprise therefore that this legal apparatus has become a lot more toxic of late, now that the Obama administration and many progressive democratic states have upped the ante with more vigorous enforcement of current laws. The disastrous implementation of Obamacare will compound the trouble by driving still more workers into part-time employment, assuming that they have jobs at all.

In the face of this nonstop activity, it is totally maddening to see the economic elites—think Paul Krugman—write as if labor market regulation is too trivial an issue to command their attention. In fact, liberalization of the labor market can do more to revive the economy than those endless debates between the champions of austerity and free spending.

Let me give two examples of how this could work. When I first went to New Zealand in 1990 to lecture on the issue, the labor markets were in a state of near collapse. The major proponent of labor market liberalization was the late (and great) Roger Kerr, who then headed the now defunct New Zealand Business Roundtable. When New Zealand adopted the Employment Contracts Act of 1990, which turned the dial toward market liberalization, the effects were quite astonishing, even though many features of the older system remained. Within the next decade, that reform led to the creation of 300,000 new jobs in a country with a population of 3,600,000 people. Union participation went down from over 50 percent to about 20 percent. Monetary and fiscal policies have not and could not achieve these results.

The same results can take place in this country. Wisconsin governor Scott Walker was met with fierce opposition when he proposed a partial reform of collective bargaining agreements for public unions. Walker has told his side of the story in his recent book Unintimidated: A Governor’s Story and a Nation’s Challenge. But on these questions there is no need to take his word for it. There is independent evidence on such key issues as union decertification, budget surpluses, and property tax cuts. These reforms have an impact that the Fed cannot match.

A Single Mission for the Fed

The lessons of labor market deregulation are too large to be ignored. What goes on in Washington with fiscal and monetary policy will have a huge impact on the state of the economy. We need stability in government institutions so that neither private nor public parties have to contend with endless levels of man-made uncertainty on inflation. But in order to do that mission well, the Fed has to give its undivided attention to inflation—not employment. The dual mandate is a massive distraction. It is far preferable for the Fed to do one task well than two tasks poorly.