- Values & Social Policy

- Race & Gender

Juneteenth bequeaths a legacy of freedom, for all Americans and especially for African-Americans. The nineteenth of June marks the date in 1865 when Union troops reached Galveston, Texas, to end slavery definitively. The holiday provides an opportunity to reflect on the long tradition of liberty that pervades American culture. For all the experience of inequality, unfairness, and racism that has coursed through the nation’s history, so too has the aspiration for freedom. While we should not forget the bad of the past, it is vital to celebrate the good, the accomplishments of freedom, and the sacrifices they demanded. Remembering that legacy is never more appropriate than on Juneteenth “in the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Focusing on the emancipatory accomplishments in American history is all the more important today, in the face of efforts to redefine the movement for equality, which has long been based on the freedom of opportunity, by distorting it into appeals for “equity” that prescribe outcomes in advance, thereby degrading individual effort. This hostility to individual freedom was clearly evident in the embrace of Marxism that originally informed the Black Lives Matter agenda. Yet the real freedom tradition—the tradition from the Declaration of Independence through Juneteenth and until today—is richer than the bizarre ideologies promoted by activists and media during recent decades. As an antidote to wokeness, it is salutary to turn to three brilliant writers from the African-American tradition—Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and Richard Wright—who testify to the rich breadth of freedom thinking.

“I Do Not Weep at the World”

Despite the differences among these writers, they share literary accomplishment. We turn to them not as career politicians who advocated particular programs, nor as social policy analysts, although at times they came close to policy in their descriptions of the experiences of African-Americans in the unequal structures of American society. What distinguishes them is their excellence in a medium that has a special relationship to freedom: literature or, more broadly, the aesthetic imagination. Through literary creations, writers have been able to criticize the failures of their surroundings and to imagine alternative possibilities.

Literary autonomy acts as a role model for the autonomy, the freedom, of individuals. This is why there is a tight bond between the world of imaginative writing and the freedom movement, nowhere more apparent than in the emancipatory ambitions of these three great authors. Their thinking of liberty represents a challenge to any effort to constrain human creativity, whether as slavery, as discrimination, or as the thought and language policing of today’s cancel culture. Literature and liberty are inseparable.

Zora Neale Hurston, a heterodox and staunchly libertarian thinker, was born in Alabama and raised in the all-black town of Eatonville, Florida, where many of her stories were set. Until she was thirteen, the only whites she knew were the ones who passed in automobiles on their way to bigger cities. Soon, her father (a sharecropper and Baptist preacher), would move the family to Jacksonville. Here she was no longer treated simply as little Zora, but as a colored girl in pre–civil rights America.

Regardless, Hurston would never view herself as a victim of her circumstances—she was fiercely independent and outspoken. Hurston penned a 1928 essay about her upbringing, titled “How it Feels to be Colored Me,” and in it she writes:

I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not belong to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it. Even in the helter-skelter skirmish that is my life, I have seen that the world is to the strong regardless of a little pigmentation more or less. No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.

Sharpen her knife she did. Hurston attended Howard University and then became the sole black student at Columbia University. Despite the station of black Americans at the time, she did not endorse the collectivist dogma of the American left. Instead, Hurston believed that hurt feelings or excuses should not stop anyone from success.

While at Columbia, Hurston became a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance—a cultural revival of African-American art, fashion, and literature. Her first book was a nonfiction work called Barracoon; it contained an interview with Cudjoe Lewis, the last presumed survivor of the Middle Passage. Hurston's best-known work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was published in 1937. The characters of her books were also in battles for self-determination and individualism. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, the central figure, Janie Mae Crawford, is in a battle to liberate herself from the prejudice and violence she experiences.

Hurston forged her own path not only personally but also politically. During World War II, she began to write significant amounts about politics. In these writings, she challenged both communism and American imperialism. Hurston became a vocal opponent of the New Deal. In today’s terminology, Hurston was incredibly anti-woke; she railed against what would eventually become known as affirmative action and was vehemently against social assistance. She once wrote:

It seems to me that if I say a whole system must be upset for me to win, I am saying that I cannot sit in the game and that safer rules must be made to give me a chance. I repudiate that. If others are in there, deal me a hand and let me see what I can make of it, even though I know some in there are dealing from the bottom and cheating like hell in other ways.

Simply put, the world is not fair but that is no reason for the color of one’s skin to change how they feel about things.

“I Am an Invisible Man”

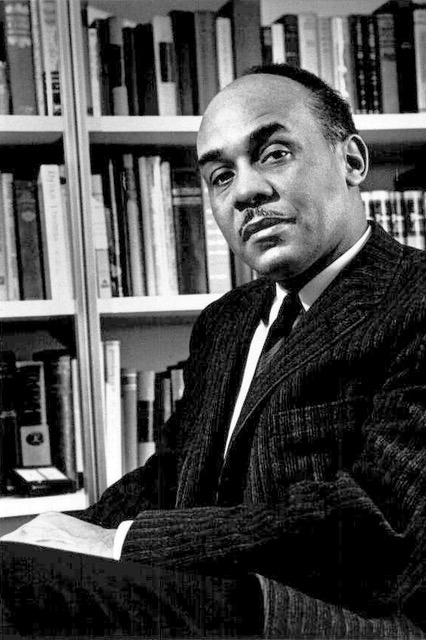

Another author, Ralph Ellison, is heralded by thinkers on both the left and the right for his refusal to be defined by his race. He was born in 1913 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma—a common post-Emancipation destination for blacks looking to establish new communities and farms. His father, a construction foreman and delivery man, loved literature and hoped his son would become a poet. Tragically, Ellison’s father would die in an accident while moving a block of ice. As a child, Ellison worked as a busboy, a shoeshine boy, a hotel waiter, and a dentist’s assistant to support the family. Eventually, he gained admission to the Tuskegee Institute.

Ellison’s most famous work, Invisible Man, was published in 1952. (His posthumous novel is titled, appropriately, Juneteenth). Invisible Man deals with a struggle for individuality in a world where black Americans were often assigned an identity. The narrator, an unnamed black man, finds not only racism to be an obstacle to his personal identity but political ideologies from his own race. Critiques of fanatical Black Nationalists and the insidious nature of Marxism are prevalent throughout the book. The narrator eventually finds his own voice, saying

I was never more hated than when I tried to be honest. Or when, even as just now I’ve tried to articulate exactly what I felt to be the truth. No one was satisfied—not even I. On the other hand, I’ve never been more loved and appreciated than when I tried to justify and affirm someone’s mistaken beliefs. . . . I was pulled this way and that for longer than I can remember. And my problem was that I tried to go in everyone’s way but my own. . . . So after years of trying to adapt the opinions of others I finally rebelled. I am an invisible man.

Ellison rejected the beginnings of what would become the continual infusion of race into American higher education. Black Americans were part of the American project, not separate—black culture was ingrained in American culture. During a protest at Amherst College over racism on campus, Ellison told an audience: “Race is a factor in American life. . . . But it is also an excuse for not seeing ourselves as we really are, for not becoming what we thought we would become, for not creating what we promised to create. Let’s stop being victims” [cited in Ralph Ellison: A Biography, by Arnold Rampersad]. Everyone, regardless of skin color, is ultimately in control of their own destiny. We should not view ourselves as victims of our circumstances; instead, we must craft ourselves into what we are—personal identity does not derive completely from one’s race.

“Writing Was My Way of Seeing”

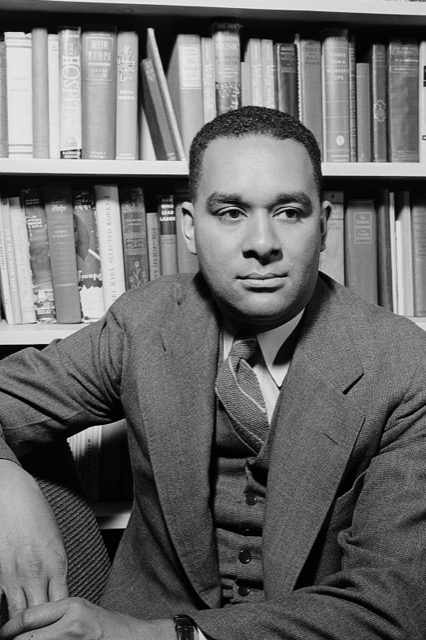

Ellison’s longtime friend Richard Wright also deviated from the conventional path of black intellectual thought. He was born in 1908 in Mississippi. His grandparents had been slaves, and both his grandfathers had fought against the Confederacy, one joining the United States Colored Troops, the other, having escaped slavery, enlisting in the Navy. The meaning of Juneteenth was therefore inscribed in the family history. Wright moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration. His novel Native Son of 1940 and his 1945 autobiography, Black Boy, were very successful, making Wright the first bestselling African-American author. In his writings, over decades, he described the conditions of African-American life and the virulence of racism.

In Chicago, Wright became involved with the Communist Party, joining in 1933 and remaining a member until the early 1940s. It was an era, the depths of the Great Depression, when intellectuals fell under the sway of communism. But as party members, they had to face demands to subordinate their intellect to directives from Moscow, the dramatic shift in world politics when Stalin entered a pact with Hitler in 1939, and the manipulative behavior of Communist leaders toward their own members. Wright’s eventual break with the party is one example of the many departures from communism that marked American—and not only American—cultural life in the face of Stalinism. Wright has much to contribute to the tradition of thinking freedom through his analysis of his experience with Communists. As an increasingly existentialist thinker, he insisted on the individual’s claim to autonomy and dignity, whether against bigoted structures of racial discrimination or against the authoritarian control of a political party.

Wright makes his criticism of communism explicit in his epic novel The Outsider of 1953, written in the midst of the Cold War, when few could have any illusions about Soviet ambitions: the Iron Curtain had long ago fallen across Europe. The novel looks back to the 1930s, describing a scene in which the protagonist has just been recruited into a Communist cell, despite his own internal doubts. Suddenly, he witnesses how a party boss dresses down a dissident party member:

“Goddamn your damned feelings! . . . Who cares about what you feel? Insofar as the Party is concerned, you’ve got no damned feelings. . . . And being a Communist is not easy. It means negating yourself, blotting out your personal life and listening only to the voice of the Party. . . . Don’t think that you are indispensable because you’re black and the Party needs you. Hell, no! The Party can find others to do what it wants! . . . The Party needs this obedience to carry out its aims. And what are those aims? The liberation of the working class and the defense of the Soviet Union.”

The Communist Party claimed a monopoly on advocating for African-American causes but in fact only exploited them for other goals.

Wright makes the internal hypocrisy of communism crystal clear: the party preaches liberation but demands subordination. At the core of Wright’s anti-communism is his insistence on individual freedom. In an important earlier autobiographical essay, “I Tried to be a Communist,” published in the Atlantic in 1944—this was his public break with the party—he linked his resistance to the Communist demands to the strength he had developed in the face of adversity in America: “It was not courage that made me oppose the party. I simply did not know any better. It was inconceivable to me, though bred in the lap of Southern hate, that a man could not have his say. I had spent a third of my life traveling from the place of my birth to the North just to talk freely, to escape the pressure of fear. And now I was facing fear again.” In other words: racism in the South and communism in the North were twin forms of abuse.

For Wright, the ex-Communist, the crux of the matter was his refusal to succumb to fear, a refusal grounded in his commitment to writing and the very core of his being: “My writing was my way of seeing, my way of living, my way of feeling; and who could change his sight, his sense of direction, his senses?”

Richard Wright wanted to have “his say”—no language policing for him, whether in the old Communist manner or today’s woke talk. Ralph Ellison advocated for black Americans to craft their own identities in the midst of people and ideologies telling them who to be. Zora Neale Hurston’s free-thinking libertarianism and anti-collectivism were entirely her own liberated path. Together these three writers remind us of the treasure of freedom which we celebrate on Juneteenth.