- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Middle East

- Security & Defense

- US Defense

- US Foreign Policy

- Terrorism

- History

- Military

- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

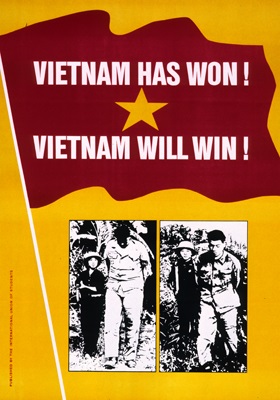

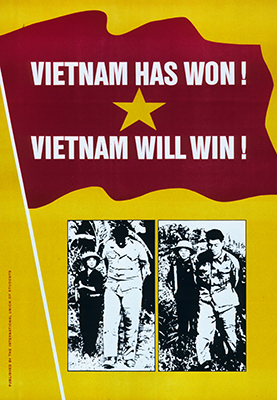

In the iconic movie Apocalypse Now, the protagonist, Captain Benjamin L. Willard (played by Martin Sheen), wakes up in a hotel nursing a massive hangover. “Saigon,” he grumbles. “Shit. Still in Saigon.” Forgive Americans for waking up today with a massive twenty-year hangover and muttering similar sentiments. Kabul has fallen, and the Taliban now rule Afghanistan. The final scenes are not helicopters lifting personnel off the roof of the U.S. Embassy, but military transport aircraft departing Kabul airport with throngs of desperate Afghans overrunning the terminal hoping to leave the country. America’s longest war is over, and it ended with a thorough defeat of the U.S. of A. The parallels with the end in Vietnam forty-six years ago are striking.

The postmortems will soon be inked, but for now it is instructive to compare the similarities of the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975 and Afghanistan in 2021. Both were unpopular governments backed by the United States, and both collapsed shortly after American forces were withdrawn from the conflict. The time between the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973 and the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975 might have been a more decent interval, but the reasons for the collapse were nearly the same. Bereft of American troops and airpower, the local military that the United States had created and nurtured could not stand up to a full-throated offensive launched by its opponent.

Last month when he reiterated his decision to withdraw American forces from Afghanistan, President Joe Biden stated, “We provided our Afghan partners with all the tools—let me emphasize: all the tools, training, and equipment of any modern military. We provided advanced weaponry. And we’re going to continue to provide funding and equipment. And we’ll ensure they have the capacity to maintain their air force.” All of which might be true, but in the end, irrelevant. What the United States could not provide to the Afghan government or its armed forces was the competence to properly administer its military instrument and the courage to fight. When the end came, it came quickly.

The same held true of the end in Vietnam. When the North Vietnamese army launched its Spring offensive in March 1975, its objectives were modest: Isolate and seize Buon Ma Thuot, consolidate its gains in the Central Highlands, and prepare a general offensive to seize the remainder of South Vietnam the following year. But after the South Vietnamese Army started backpedaling, a tactical withdrawal soon turned into a rout that ended with a North Vietnamese tank crashing through the gates of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. To be sure, elements of the South Vietnamese Army did fight, but not enough to make a difference. In the end they were forsaken by an incompetent government that lost control of the military situation.

South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu fled to Taiwan and then to London. He died in Massachusetts in 2001, shortly after the 9/11 attacks that precipitated the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. The Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, is now in exile. History has come full circle.