- Economics

- History

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

One result of the financial crisis and the ensuing global economic slowdown has been a revival of interest in the thinking of John Maynard Keynes. Much of what is being written about Keynes is an attempt to make him relevant to today’s problems and to persuade a modern audience that Keynes was right about a lot of things. Along these lines, economists Roger E. Backhouse and Bradley Bateman have recently authored, Capitalist Revolutionary: John Maynard Keynes.1 Backhouse is a professor of history and the philosophy of economics at the University of Birmingham in Britain and Bateman is a professor of economics at Denison University

Backhouse and Bateman argue, as the book’s title implies, that although Keynes wanted a substantial amount of government intervention, he did believe in preserving large elements of capitalism. This part of the book is somewhat persuasive, although their discussion of Keynes’s famous “socialization of investment” advocacy was not completely convincing. But the authors also have another important theme: They argue against the classical liberal view that government should basically keep its hands off the economy. Their attempt fails. They get some basic and important facts wrong, have trouble accounting for the stagflation of the early 1970s that persuaded many economists to abandon the Keynesian model, often misstate the views of Keynes’s critics, and occasionally use subtle shifts in language and even ad hominem attacks to undercut the views of free-market economists, most notably Milton Friedman.

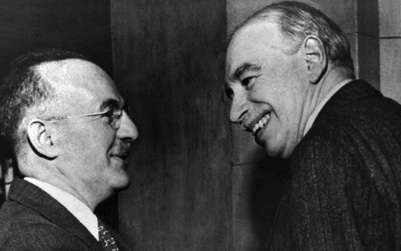

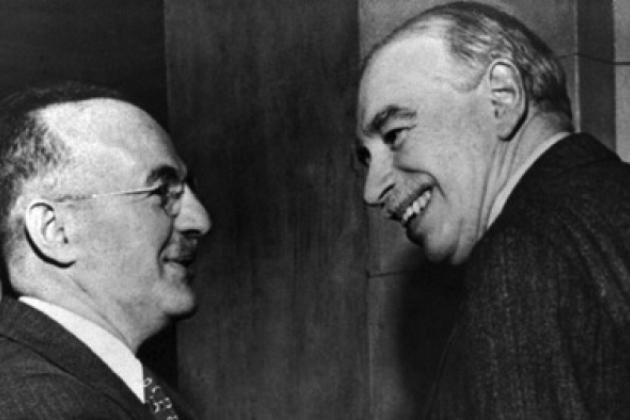

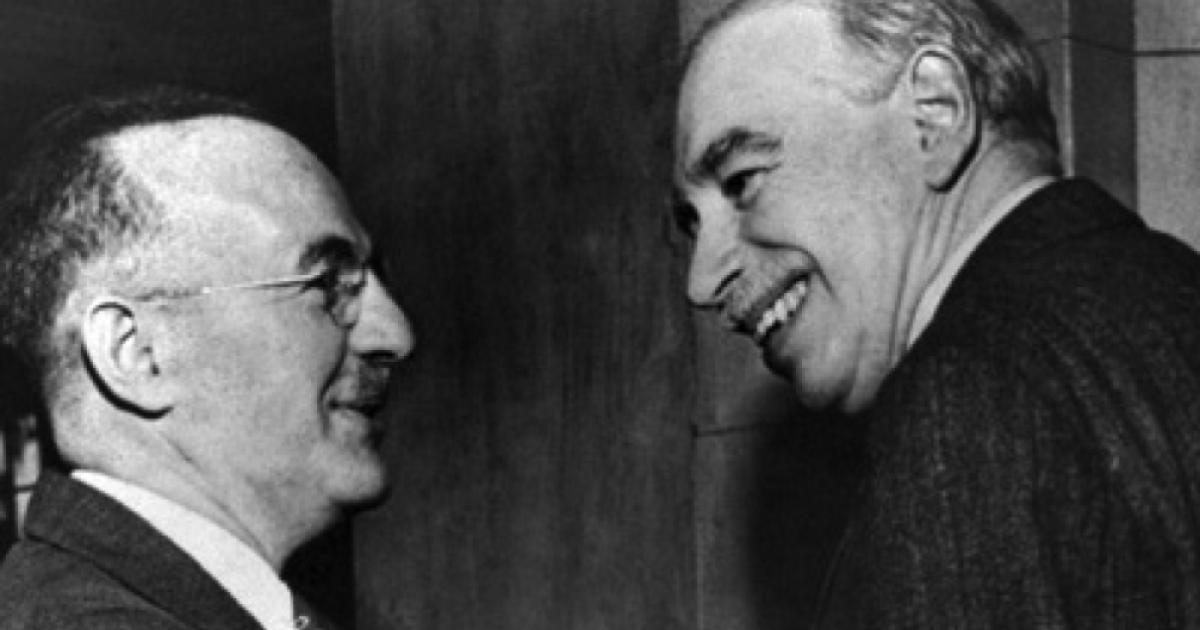

Photo credit: International Monetary Fund (Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury, Harry Dexter White, with John Maynard Keynes on the right)

A basic important fact that the authors get wrong is their description of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. A major component of Roosevelt’s first New Deal, they write, was his plan “to raise industrial output by diminishing the monopoly power of big business.” In fact, the opposite was true. Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act, enforced by the National Recovery Administration (NRA), cartelized the major industries, forcing them to raise their prices. In short, FDR’s goal was to increase monopoly power. At the higher monopoly prices, customers wanted less output, not more, and the NRA “succeeded” in slowing the recovery. Luckily for FDR, the Supreme Court overturned the National Industrial Recovery Act and the pace of the economic recovery increased.

One view that Keynesian economists held most dear in the 1960s was the idea that there was a stable tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. A government could achieve permanently lower unemployment, they thought, only by engineering permanently higher inflation. According to this view, inflation and unemployment couldn’t rise together. Then came the early 1970s, the era of so-called “stagflation”—slow or negative growth combined with high inflation. It was this combination, more than any theoretical argument, that brought down the Keynesian model. Even Milton Friedman, a major theoretical critic of the Keynesian model, said as much.

Some Keynesians did argue correctly that one could have both inflation and unemployment rise together if the economy experienced a “supply shock,” a large reduction in the supply of an important resource. Then, an economy could have stagflation and its performance could still be consistent with the Keynesian model.

Keynes believed in preserving large elements of capitalism.

Indeed, that is the argument that Backhouse and Bateman make, pointing to the fact that in late 1973 and early 1974, OPEC almost quadrupled the price of oil. James Hamilton, an economist at the University of California, San Diego, whom surprisingly the authors do not cite, found a connection between this increase in the price of oil and the recession of late 1973 to early 1975. To Backhouse and Bateman, and to Hamilton, this increase in oil prices is enough to account for the recession.

I have my doubts, however, as, apparently, do many other economists for whom the stagflation was Exhibit A against the stable inflation/unemployment tradeoff. My reason is a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation. The eight-dollar-per-barrel increase in the price of oil (from $3 to $11), given that the United States was importing four million barrels per day (mbd), should have cut real U.S. income by $12 billion a year (4 mbd times $8 times 365 days). At the time, that $12 billion was less than one percent of the U.S. GDP of $1.4 trillion. So, the OPEC price increase should have cost the U.S. economy, at most, one percent of real GDP, which would, in turn, add only one percent to the price level. Yet the U.S. economy lost substantially more than one percent of GDP, while the price level in 1973 and 1974 rose by 18 percent. Thus, OPEC appears to be a small part of the stagflation story. There could be complications that make OPEC’s effect bigger. But that much bigger? That’s hard to believe.

Instead of presenting the arguments that Milton Friedman and other critics of the Keynesian model presented in the 1970s, the authors merely write, “[T]he critics of demand management saw an open opportunity and attacked Keynesianism.” Sure, they saw an opportunity, but isn’t it possible that the critics had valid criticisms? Backhouse and Bateman press the opportunistic angle, writing that “a group of economists who were well-funded by their conservative backers were quick to sharpen their attack against both Keynes and his ideas.”

I don’t know about the funding of this particular group of critics, but why is that even relevant? The authors make no mention in the book of how well or badly funded Keynesians were. The authors seem to mention the funding in order to suggest that there was something sleazy or not quite above-board about Keynes’s critics. A few lines later, for instance, they describe Friedman’s monetarism—the view that changes in the money supply are the most important determinant of short-run macroeconomic conditions—as a “creed.”

In describing the changes in thinking about free markets that occurred because of the recent financial crisis, the authors cleverly use language to stack the deck. They write, “Capitalism had been revealed to not work well, but social democracy was argued to be unsustainable.” Note the difference in the two verbs. Capitalism had been “revealed” to not work well. In other words, there is no controversy: it’s crystal clear that capitalism doesn’t work well. Social democracy, by contrast, is simply “argued” to be unsustainable. Thus, the authors leave open the idea that social democracy—the welfare state—could be sustainable.

The authors suggest that the welfare state could be sustainable.

But there is indeed serious controversy about whether capitalism works well, with pro-market economists like me claiming that it does and that the alleged failures of capitalism are mainly the result of dysfunctional government regulation. We may be right or we may be wrong, but the point is that there is controversy: there is no “revelation.” On the other hand, there is no real controversy that in the United States, according to Congressional Budget Office projections, the U.S. federal budget is on an unsustainable path, with federal government spending threatening to hit over 40 percent of GDP by mid-century, up from its post-war average of about 20 percent. And the three major components of this higher spending are welfare-state programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. This is not just an argument; these are facts.

The authors also falter when they contrast Milton Friedman’s and Keynes’s approaches to economics. “When an economist like Friedman analyses economic behavior,” they write, “he imagines utility maximization to be the highest human value.” For Keynes, they write, “there were higher values than utility maximization.” What were these higher values? According to the authors, they “involved the arts, the pursuit of scientific knowledge, and creative writing.” But that’s completely consistent with utility maximization. Those are the things that gave Keynes utility. Moreover, the fact that those “higher values” gave Keynes utility doesn’t mean that they gave the average person a lot of utility.

A good way to be a bad economist is to impute one’s own preferences to others. A little-known fact about Milton Friedman is that he loved to go to circuses. But if, in his reasoning about human action, he had assumed that most people love to go to circuses, he would have made some serious errors.

The authors quote a passage in which Keynes criticizes the love of money as a “somewhat disgusting morbidity.” In summarizing this passage, the authors write, “So, for Keynes, capitalism was emphatically not an end in itself.” But that’s not an accurate summary of Keynes’s thought at all. Keynes probably did not see capitalism as an end in itself, but that’s a different point altogether. One can see capitalism as a political end in itself and be as critical as Keynes was of the love of money.

The great thing about capitalism, if we take capitalism to mean “economic freedom,” is that it allows people to focus on what they value. So, for example, under capitalism, a wealthy person can choose to be a miser. Or that wealthy person can give generously to charitable causes, as many do. And, incidentally, even the miser benefits others by investing in capital that increases workers’ productivity and, therefore, their real wages. So, capitalism can be a political end precisely because it allows people to pursue their own ends. But such distinctions elude the authors.

The great thing about capitalism is that people choose what they value.

One of Keynes’s most famous statements in the last chapter of his 1936 classic, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, is the following:

I conceive, therefore, that a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment will prove the only means of securing an approximation to full employment.

On its face, this sounds simply like advocacy of socialization of investment. But there has been much discussion among economists about what Keynes really meant here. Backhouse and Bateman argue that Keynes didn’t mean government deciding where and how much to invest. They point out, correctly, that in the same paragraph, he rejected “State Socialism.” According to the authors, all Keynes meant was that, somehow, government had to assure “that the aggregate level of investment matched the level of savings that would take place at full employment.” Their claim, which other economists have also made, is plausible. The next-to-the-last sentence of Keynes’s paragraph supports it. Keynes writes:

If the State is able to determine the aggregate amount of resources devoted to augmenting the instruments [of production] and the basic rate of reward to those who own them, it will have accomplished all that is necessary.

But in the very next sentence, Keynes drops this bombshell:

Moreover, the necessary measures of socialization can be introduced gradually and without a break in the general traditions of society.

Thus, it sounds as if Keynes is advocating gradual socialism rather than socialism all at once.

The book does leave one strongly positive impression of Keynes. A failing of many economists nowadays who work for high-level politicians is that in their later careers, they pull their punches. Criticisms they would have made of other politicians for bad policies are criticisms they tend not to make of the politician they previously worked for. Keynes did not have that failing. The authors write:

[D]espite his long commitment to the Liberal Party, he was willing to point his pen at people and policies regardless of the party from which they originated. . . . Keynes’s Essays in Biography, published in 1938, contained a portrait of the Liberal leader Lloyd George, with whom Keynes had recently worked, that was very unflattering. . . . Keynes worked first and foremost to achieve what he believed was in the best interests of Britain, which was not always the same thing as what was best for particular parties or individual politicians.

Good for Keynes.

1Roger E. Backhouse and Bradley W. Bateman, Capitalist Revolutionary: John Maynard Keynes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 198 pp., $25.95).