- Economics

- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

The hottest topic in Michigan today is not the looming presidential election. Rather, it is Proposal 2—“Protect Our Jobs,” which will constitutionalize collective bargaining in the state for public sector unions. As drafted, the proposal gives to “the people . . . the rights to organize together to form, join, or assist labor organizations, and to bargain collectively with a public or private employer through an exclusive representative of the employees’ choosing”—provided that this proposal is not preempted, or overridden, by federal labor law.

It is not clear from its general language whether Proposal 2 will roll back any of the modest reforms that Michigan now has put in place as a counterweight to union power, but the initiative is certainly intended to bolster union power in the state.

Illustration by Barbara Kelley

Michigan, long an economic basket-case, has started to turn the corner under Republican Governor Rick Snyder, who knows that the state’s fortunes won’t improve if it doubles down on a system of labor law that has proven itself to be a major failure. As the governor has argued, Proposal 2 is a step in the wrong direction.

We should be profoundly skeptical of any proposal that aims to improve the lot of the “people” by giving some people rights that necessarily bind others—in this instance, the public at large or the owners and employers of private firms. The folks on the receiving end of these collective bargaining laws are people too. No system has a prayer of long-term success if the gains that some people get by state coercion are smaller than the losses those laws inflict on others.

In this instance, the virulent economic protectionism of the “Protect Our Jobs” provision means that the losses will far outweigh the gains. Proposal 2 does not remove transactional frictions or regulatory barriers from the economy. Rather, it is a partisan call to benefit unions and union members at a time when most states around the country are rightly questioning whether the special protections for government employees have gone too far, especially on such key matters as pensions, health care, and work rules.

The key argument put forth by the unions in favor of the new proposal is that collective bargaining is the only thing that stands between “the people” and the abyss—that is, the loss of their status as members of the middle class. Unfortunately, this inflated claim relies on a version of history that overlooks the true costs associated with collective bargaining.

In offering his sympathetic account of Proposal 2, New York Times reporter Steven Greenhouse relies on anecdotes to carry the argument. He quotes Ivy Bailey, an elementary school teacher in Detroit, whose father was lifted into the middle class with the help of collective bargaining. His rich GM contract allowed him to send his two children to college. Bailey argues that collective bargaining is needed because workers can never “trust the boss to do the right thing.”

The End of Unions?

A larger view of the situation makes clear the shallowness of these claims. The United Automobiles Workers’ aggressive bargaining strategy no doubt did raise the wage levels of its members during its heyday. But the increases obtained through the threat of strike could not be sustained in the long run against competition from other companies, including the Japanese firms that opened up new plants in the southern United States.

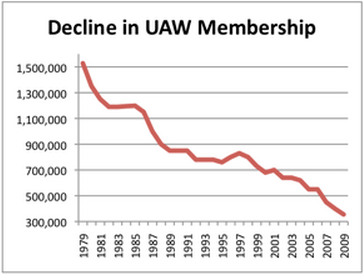

UAW membership tumbled from over 1.5 million members in 1979 to 355,000 members in 2009. To be sure, union membership has increased modestly to 380,000 members in 2011 in light of the recovery of the automobile industry.

Credit: World Socialist Website

Even so, the long-term trend remains that unionized American companies will continue to lose market share to more efficient and nimble foreign companies, which are not saddled with such onerous union contracts. How did unionization benefit those workers who lost their jobs during the relentless downsizing driven by the high costs of union labor? These folks were driven out of the middle class when their jobs evaporated.

The toxic job climate in Michigan led to a consistent out-migration of displaced auto workers to other states. Indeed, buffeted by the implosion of the automotive industry, Michigan was the only state in the nation that suffered a population decline between 2000 and 2010, as people left in search of better opportunities for new employment.

Nor does it make any sense to defend the system of collective bargaining on the ground that bosses cannot be trusted to do the right thing. That position assumes that the employment relationship between labor and management is a zero-sum game. The unstated rationale is that the best way for firms to prosper is at the expense of the employees, who in turn can only thrive by playing hard-ball in response. In these games, unions have tried to milk firms without bankrupting them. But often, their calculations are less than exact so that, in the end, the UAW’s unprecedented 1979 collective bargaining agreement ended up backfiring on its members, who paid a heavy price down the road.

And it is all so unnecessary. A selfish firm can’t maximize profits by demonizing its workers, or by keeping them perpetually on edge. Firms exploit the gains from trade by combining the skills of different workers in constructive ways. Successful firms generate mutual gains from cooperation and trade, so that workers will stay at their current jobs even when they are free to go elsewhere. The non-union automobile firms that prospered while GM faltered did not mistreat their workers by, for example, driving them to the brink of exhaustion.

Instead, they offered their workers a competitive wage, with prospects for advancement as the efficiency and productivity of the firm continued to improve. Their expanding market share increased job security for existing workers and created job opportunities for new workers. A successful business offers far more worker protection than a union-backed guarantee of seniority in a firm that is likely to lose market share or even go bust. Just ask all of the former Ford, GM, and Chrysler workers.

Unions: State-Sanctioned Monopolies

The real dispute is over how best to conceive of collective bargaining. Under the standard union account, backed by many progressive intellectuals, collective bargaining should be a “fundamental right.” But the reality on the ground is quite different. Collective bargaining through an exclusive agent is a fancy label for the union exertion of monopoly power sanctioned by the force of the state.

We know that competition outperforms monopoly in all industries. With goods, lower prices lead to higher sales and greater consumer satisfaction. Product monopolies shrink the overall social pie as they increase the monopolist’s share of wealth, which is why anti-trust law takes a dim view of firms that agree to restrict and raise profits for their mutual benefit.

Labor monopolies replicate the bad qualities of product monopolies; monopoly wages lead to lower levels of employment, diminished job opportunities for non-union workers, and higher consumer prices for all.

Indeed, union monopolies, currently insulated from the anti-trust laws and protected by collective bargaining regimes at the federal level, are unambiguously worse than product monopolies. The large unified firm always has incentives to adopt the most efficient mode of production, so that its shareholders can maximize their profits. Not so the union, which must preserve its diffuse membership base.

Like any industrial cartel (think OPEC), it must preserve jobs for members instead of reducing the size of the work force to maximize profits. The union cannot cut positions that will jeopardize its political support. It is for that reason that unions fight for costly seniority systems that increase the odds of firm failure, by forcing firms in hard times to retain their older, more expensive, and often less productive workers. These structural infirmities help explain why union membership in the private sector has shrunk to under 7 percent today, down from its 35 percent high in 1954. The unionized firm cannot compete effectively with its non-unionized rival.

The Public Sector Morass

The situation is, if anything worse, with public sector employment. Private firms have the option to exit the state and to take workers desperate for jobs with them. Public agencies have no such options. Once they are subject to unions that cannot be broken or removed, the only way to fend off financial ruin is to negotiate givebacks with balky unions. Ultimately, that awkward process will generate some concessions, for no union wishes to kill the political goose that lays the golden eggs.

But these concessions will be too little, and too late, forcing immense fiscal strains on the local governments, which in turn will drive more prosperous firms and individuals from the state. Instead of modest and sustainable improvements in its current financial position, Michigan could easily fall back into its historical downward spiral.

The situation is doubly perilous because it is clear that many better run states—think Indiana, next door—will respond to the opportunity by courting the firms and individuals that face a bleak future should Michigan enter into the brave new world of Proposal 2. Interstate competition is, of course, a powerful corrective to the unwise economic policies of any given state, so Michigan’s losses, should Proposal 2 be adopted, will translate into the gains of other states. But by the same token, success in Michigan could lead to similar proposals in many other states, spreading the germ further throughout the nation.

There is a bleak constitutional irony in this situation. One hundred years ago, the question of the constitutionality of collective bargaining was very much on the front agenda of the American labor movement. In two decisions, Adair v. United States (1908) and Coppage v. Kansas (1915), the United States Supreme Court struck down laws that made it illegal for employers to fire union members, which spelled the end of state-imposed collective bargaining agreements. Those early decisions did not represent a reflexive defense of the principle of freedom of contract, irrespective of its social consequences. That same Court, after all, consistently enforced anti-trust laws designed to stop industry combinations in restraint of trade, precisely because of their adverse social consequences.

Many progressive historians viciously attacked both Adair and Coppage, claiming that it was unwise to adopt constitutional tactics to thwart the actions of the ordinary political processes. Today, we see how the cycle has been reversed. Now, constitutional tactics at the state level are being used to enshrine a strongly anti-competitive system that promises major social dislocations.

These programs are self-defeating, insofar as they put heavy pressure on non-union workers who are driven to part-time jobs that offer no prospect of moving to, or staying in the middle class. I have always supported Adair and Coppage on the ground that pre-competitive policies should enjoy constitutional protection. But constitutional politics are always high stakes games.

For now, the effort to lock in a monopoly structure poses a very large threat to Michigan. The citizens of that state should recognize that “the people” as a whole do not benefit from labor laws that rig the system in favor of the few. They should reject Proposal 2 economy oligarchy it begets.