- Law & Policy

- Regulation & Property Rights

- Health Care

- Economics

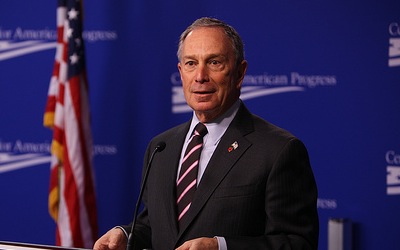

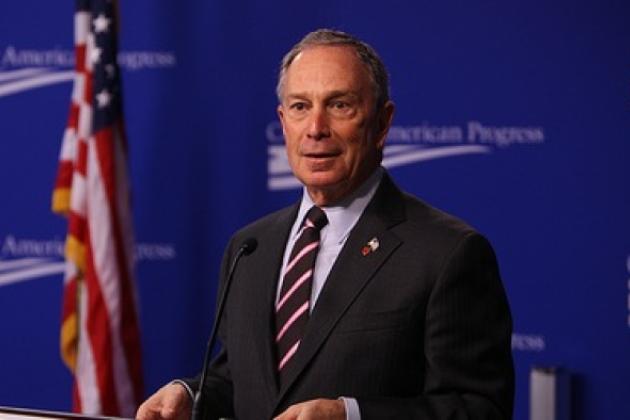

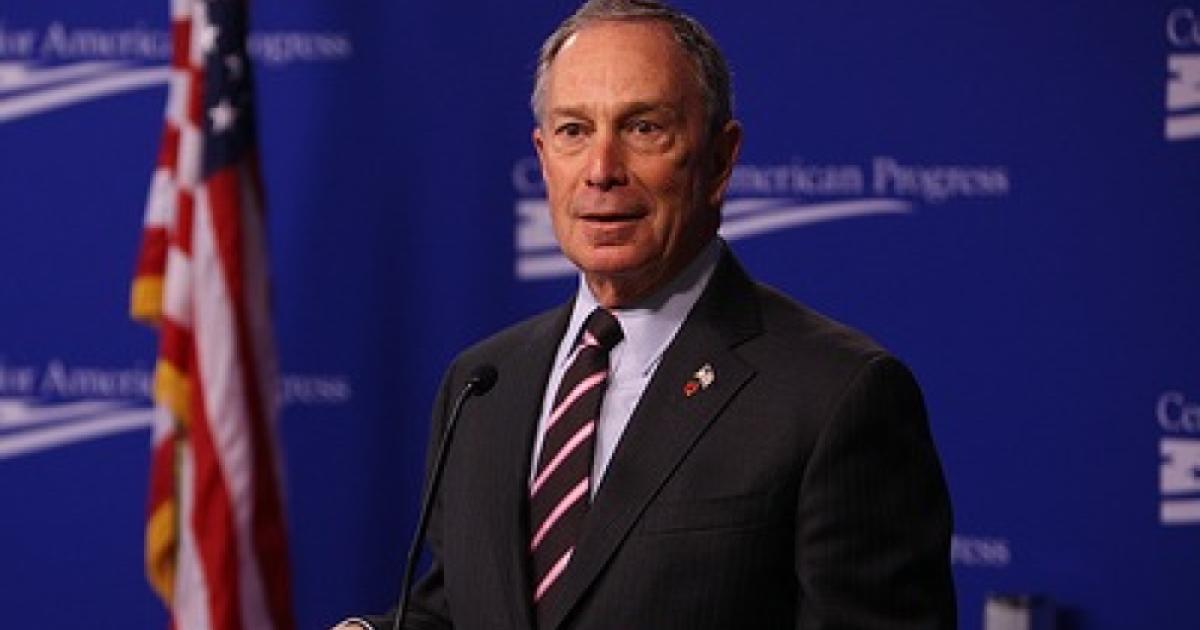

New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s big soda ban ran afoul of reason and common sense, or so decided New York Supreme Court Judge Milton Tingling last month. Bans on some big sugary drinks but not others, and on sales of big sugary drinks at some retailers but not others, are arbitrary and capricious, said the judge. The city has appealed, so we will have to wait to see if common sense rules in New York’s appellate courts as well.

But Mayor Bloomberg should not despair. Even if the appellate judges agree with Judge Tingling, there is a simple remedy if the mayor wants to press ahead with his anti-obesity agenda. He can ban all big sugary beverages at all retail venues and it will no longer be arbitrary and capricious. Unless, of course, the courts are willing to go so far as to say that the city has no legitimate concern with obesity or that there is no basis on which the city could conclude that banning big sugary beverages will combat obesity.

Photo credit: Center for American Progress

The latter—concluding that there is no evidence that big sugary beverages contribute to obesity—seems very unlikely. Unless the mayor provides no evidence whatsoever on the relationship between gargantuan sugar drinks and obesity, courts will almost certainly defer to the policy-making bureaucrats and politicians.

But if the courts are willing to be a bit adventuresome, they might ask by what authority the mayor and the city have entered into the obesity combating business. Or they might ask why individual New Yorkers are not responsible for managing their own girth and weight. Don’t people have a right to be obese?

Whatever authority the City of New York and its mayor have they get from the State of New York. States have always been presumed to have the power to protect and promote the public health, so assuming the state has delegated that authority to the city, it sounds like the mayor is well within his rightful powers in seeking to regulate big sugary beverages and other things that affect human health.

Of course, a lot of things affect human health. Isn’t this a slippery slope? If the mayor can ban big sugary beverages, surely he can ban four-layer chocolate cakes and 32-ounce steaks. And if, in the interest of promoting good health, he can ban oversized servings, why can’t he mandate the eating of carrots, broccoli, and even brussels sprouts? The possibilities for the ambitious nanny mayor would seem to be without limit.

But not even Mayor Bloomberg claims absolute power, so there must be some basis for distinguishing the respective roles of the state and the individual in the promotion and protection of the public health. Well yes, there is—the public health. The state (or city in this case) is in the public health business. Individuals have responsibility for their personal health. But if public and private responsibility and authority relate to public and private health respectively, what is the mayor’s justification for banning big sugary beverages for which there is demonstrated private demand?

There are, the mayor tells us, significant social costs of obesity. Obese people have more health problems than the average person. The resulting costs, particularly when the obese are poor (as are a disproportionate number), are borne by the taxpayers and, under Obamacare’s mandated community-rated health insurance, by the mostly non-obese, healthier, and insured. These are what some economists might call the external costs of choices made by the obese. The mayor’s idea is to limit their choices to alternatives less likely to contribute to obesity, namely smaller drink portions, leading, he seems to think, to less obesity and fewer social costs. In other words, the Mayor is not insisting that people take care of themselves. Rather, he is insisting that they stop imposing costs on others and on the government.

This is a commonplace argument made in defense of all manner of regulation of private activity. Hygiene standards for restaurant employees protect restaurant patrons, not restaurant workers. Building codes protect neighbors’ property values, future purchasers, and the public’s safety, not the original homeowner who might prefer a home built to their own, perhaps less expensive or more aesthetically pleasing, specifications. Corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) standards exist to conserve scarce petroleum resources and reduce pollution, not to protect car owners from high gas prices. Prohibitions on smoking in public places protect bystanders, not smokers. In Oregon, where the state senate has just passed a bill banning smoking in cars occupied by children, the obvious purpose is to protect the health of children, not of smokers.

But Oregon Senator Brian Boquist says he voted for the smoking ban not to protect children but for reasons similar to those Mayor Bloomberg relied on to justify his prohibition of big sodas. Citing Obamacare and the expansion of Medicaid to 260,000 more Oregonians, Boquist said, “If we have to pay the bill, we get to make the rules.” This sounds reasonable and, no doubt, has political appeal, but there is a serious flaw in this argument. The state does not have to pay the bill.

The social costs Mayor Bloomberg and Senator Boquist seek to avoid are not the external costs of choices made by obese individuals or smoking parents. Rather, they are costs willingly assumed by the drinker or smoker that society has voluntarily chosen to bear. In other words, they are self-imposed by the state. Government has chosen to assume the costs of healthcare for the poor.

Oregon’s Senator Boquist may fairly object that the federal government has imposed costs on state government, but in that case, his beef should be with the federal government, not the smoker imperiling the health of the child. Mayor Bloomberg might also object that his city is forced by the federal government to share in the disproportionately higher healthcare costs of the obese, but that has nothing to do with the choices made by those who like a really big soda. The only external costs inherent in obesity are those associated with narrow airline seats and crowded subways.

Failure to distinguish between public costs in the form of harms inflicted by one private citizen on other private citizens, and public costs in the form of expenditures on government programs of any type, has serious implications. Not very many years ago, state governments (and the plaintiff’s bar) struck gold in a series of lawsuits against tobacco companies. The theory of these lawsuits was similar to the theory of the Bloomberg ban on big sugary beverages.

Smoking causes health problems that impose large costs on state funded healthcare programs. Because smoking causes clear and measurable harm to third parties in the form of secondary smoke, there was never a need to justify smoking regulations on the basis of prospective healthcare costs to the state. But when some creative plaintiffs’ lawyers and ambitious attorneys general conceived of the idea of suing tobacco companies for billions of dollars, they recognized that states likely had no standing to sue for damages from secondary smoke harm to third parties, and even if they did, such cases would yield little in the way of damages.

So their theory was that states are entitled to recover for the cost of healthcare provided for decades under state-funded healthcare programs. Their cause was made easier by bad behavior on the part of tobacco companies and by a growing public disdain for smoking, but their theory of liability was suspect given that state governments had voluntarily assumed responsibility for the costs they sought to recover from big tobacco. Because the tobacco companies chose to settle almost every case, the idea that states can turn perfectly legal activities into tortuous acts by assuming responsibility for costs voluntarily incurred by private parties was seldom put to the test in court.

If the theory of the state claims against tobacco companies is valid, there is no reason New York can’t sue producers and vendors of oversized sugary beverages for obesity-related healthcare costs borne by the city. Indeed, if the city can prove that consumption of sugary beverages of any size, or any other food or drink, that causes health problems for which the city has assumed responsibility, the theory seems to call for regulation or a lawsuit.

Cities and states can create opportunities to sue for damages simply by assuming responsibility for costs previously borne willingly and legally by their citizens. Such lawsuits provide much needed revenue to cash-strapped governments and a bonanza for plaintiffs’ lawyers, but they erode the principled relationship between rights and responsibilities on which our economic and political institutions depend. We substitute the nanny mayor, who regulates to avoid costs the government has chosen to bear, and avaricious government lawyers, who sue to recover those costs borne by the government after the fact, for the rule of law.

There is a fundamental difference between the consumer made ill by drinking too much of an unadulterated beverage and the consumer made ill by, let’s say, a mouse in his beverage. The legal rights of the latter have been violated; not so the legal rights of the former. Regulation and lawsuits based on the latter protect liberty and enforce responsibility. The consumer of the adulterated beverage has suffered an invasion of liberty and the producer or seller of the beverage is held responsible for that invasion and is properly regulated to prevent future invasions. Regulations that prohibit individuals from otherwise legal activities because those activities are thought to result in costs government has voluntarily assumed, thereby relieving other individuals of costs they are otherwise legally obliged to bear, infringe on the established liberties of some while excusing others from their responsibilities.

Not all good and noble ends warrant government means. Obesity is a serious problem for a growing number of Americans. Mayor Bloomberg is to be admired for wanting to do something about that. But he is mistaken to believe that New Yorkers or Americans will benefit from restrictions on liberty and relief from responsibility. It could be that a prohibition on the sale of giant sodas will save a few from obesity; in any event, it is only a minor constraint on personal choice. But history demonstrates that one insignificant limit on freedom invites another and another, just as small handouts lead to more small handouts and eventually to dependency.

In his 1968 book Desert Solitaire, author and essayist Edward Abbey urged that the keepers of our national parks and wilderness areas should “let [visitors] . . . take risks, for godsake, let them get lost, sunburnt, stranded, drowned, eaten by bears, buried alive under avalanches—that is the right and privilege of any free American.”

Just because government has voluntarily undertaken to rescue those in trouble, suggested Abbey, government should not forbid people from taking risks. In the same spirit, we should urge Mayor Bloomberg to let New Yorkers drink enormous sodas, if that is what they prefer. Of course, protect those who cannot protect themselves and provide for those who cannot provide for themselves, but don’t allow those imperatives to threaten the liberties and cloud the vision that made you a very wealthy man. Do let them get eaten by bears, take financial risks, and drink as much soda as they want.