- World

- Law & Policy

- Civil Rights & Race

- History

In 2000 the Hoover Institution Archives acquired the papers of the American public philosopher Eric Hoffer. The papers fill 75 linear feet of shelf space and contain extensive draft writings and journals by Hoffer, many of them unpublished. They are now open for research.

Often known as the longshoreman philosopher, Hoffer worked on the San Francisco waterfront and gained national prominence with his first book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, published in 1951. It was praised by public figures ranging from Arthur Schlesinger Jr. to Bertrand Russell. Following the events of September 11, some commentators have pointed out that Hoffer’s analysis of “the true believer,” although written with the followers of Hitler and Stalin in mind, was also applicable to Islamic fundamentalists. The book has since been reprinted. After The True Believer, Hoffer published eight more books. He died in May 1983.

His papers were bequeathed to Lillian (“Lili”) Fabilli Osborne, who met Hoffer for the first time shortly before The True Believer was published. Her husband, Selden Osborne, worked on the waterfront and knew Hoffer well. Hoffer became a friend of the family, and Lili persuaded him to keep his papers and rough drafts. She carefully preserved this material after his death and later placed it in the Hoover Archives for safekeeping. Hoffer’s friend and attorney Cameron Wolfe “was essential to me in paving the way to the Hoover Institution Archives,” Lili Osborne recalled. She also acknowledged the encouragement of independent filmmaker John McGreevy and the role of former Hoover archivist Charles Palm, who patiently negotiated with her over a 10-year period. The material was eventually purchased by the Hoover Institution, with support from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundation. Lili Osborne, who lives in San Francisco, retains control of the copyright to Hoffer’s writings.

The Bare Bones of a Life

Hoffer was born around the turn of the century in New York City. All we know about his early life is what Hoffer chose to tell us. His father was a cabinetmaker. His mother fell downstairs while carrying young Eric in her arms, and two years later she died. When she died he went blind, or partially so. “Did the fall cause those things? I don’t know,” he told a New Yorker writer. “I’ve been asked these things over and over, and it’s all the vaguest, the most blurred thing in the world to me.” Then, at the age of 15 he recovered his sight and experienced “a terrific hunger for the printed word.”

The year of his birth, usually given as 1902, was almost certainly 1898 (Lili Osborne accepts this as the more likely date). Hoffer’s parents came to the United States from Alsace, and Hoffer himself spoke with a German accent throughout his life. He never left the United States except for a few hours’ excursion at the Mexican border. Perhaps the most pro-American public philosopher of his day, Hoffer never had a passport and his birth certificate has not been located.

Nothing about his early life has been independently verifiable. His own recollections are the sole source of all that we know. His parents left no documentary trace; he had no brothers or sisters; he attended no school; and the German immigrant Martha Bauer, his surrogate mother after Elsa Hoffer’s early death, returned to Germany around 1920.

“I did not cry when they died; they who begot me, nursed me, reared me,” Hoffer wrote in an unpublished 1959 note. “Though their faces are still alive in my mind I gave them hardly a thought as I wandered up and down the land, dodging hunger and grieving over the world.”

Around 1920 Hoffer left for Los Angeles with $300 provided by his late father’s guild of craftsmen. For the next 20 years, Hoffer was either in Los Angeles or on the move in the San Joaquin Valley as a migratory worker. Accumulating library cards along the way (none has survived), he acquired a lifelong reading habit. The only documentary evidence that has survived from that period is his Social Security application, dated June 1937. It attests that Hoffer was then living on Eye Street, Sacramento, and was employed by the U.S. Forest Service in Placerville. His age was given as 38, and his birth date, July 25, 1898. Later in life, even after Hoffer became well known through his appearances on television, no one seems to have come forward claiming to have known him in the earlier part of his life.

In one of his last notebooks (unpublished), a ghostly figure does emerge, a migratory worker whose name Hoffer never knew. In the camp, when Hoffer told stories, this man used to listen like the others, but he always seemed unmoved, never joined in the laughter. Hoffer felt his disapproval, and it worried him. Later, when he settled in San Francisco and published books, he bumped into the man on the street. He greeted Eric warmly and said, “We are all proud of you.” Hoffer was elated and speechless. Then the man said, “You are probably a busy man and I must not keep you.” They parted, and Hoffer kicked himself for not getting his name and address.

After Hoffer moved to San Francisco in 1941, the record of his life becomes fuller, even as it became less varied. Authors, it is said, have bibliographies, not biographies, and this was certainly true of Hoffer. He rarely left the Bay Area in his remaining 42 years. He rented a room on McAllister Street downtown, not far from the San Francisco Public Library, and he stayed there for many years. Then he moved to Clay Street, where he rented another room. It was described by one visitor as a “spare, sunless, almost shabby cubicle, as unrelentingly masculine as the lifelong bachelor who occupies it.”

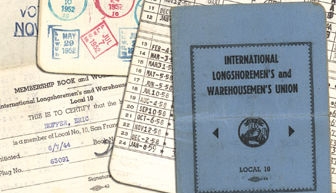

Other than the Social Security application, there is no known official record of Hoffer’s existence before he moved to San Francisco in 1941. A remarkable feature of Hoffer’s life is that (accepting the 1898 birth date as correct) he was already 53 years old when The True Believer catapulted him into the public eye. Hoffer signed up as a longshoreman in March 1943. A year earlier he had registered for the draft, at Local Board 96 in San Francisco, and within months was turned down for military service because of a hernia. His selective service card, dated July 1943, shows that he was classified 4A. It was the draft, the war, and the consequent labor shortage on the docks that gave Hoffer the opportunity to join the Longshoremen’s Union at the age of 45. In the 1940s he lost his thumb in a waterfront accident and was in the hospital for months while it was repaired with grafts from his body.

Hoffer worked on the docks for almost the next quarter-century. Working and Thinking on the Waterfront, published in 1969, describes that milieu in diary form. But the unpublished journals and notebooks in the Hoover Archives provide a fuller account, with vignettes, descriptions of conversations with longshoremen, and thoughts on the union president, Harry Bridges. Hoffer’s work routine varied, but he counted it one of the great benefits of the union that longshoremen could work when they wanted. His pay fluctuated accordingly. (In 1953, he earned $4,110 on the waterfront and $1,095 in royalties from Harper & Brothers.) By 1956 he was reporting to work three or four times a week, earning more than $5,000 that year as a longshoreman.

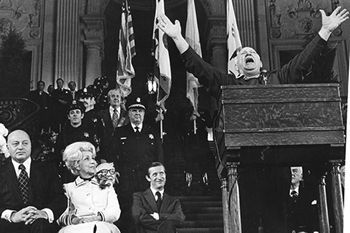

A 1956 profile in Look identified Hoffer as “Ike’s Favorite Author.” Beginning in 1963, James Day of KQED in San Francisco interviewed Hoffer for a 12-part series on public television; Eric Sevareid followed for CBS two years later. On CBS, Hoffer was full of praise for Lyndon B. Johnson, who then appointed him to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. (Video copies of the KQED and CBS interviews, and the working papers of the presidential commission, are available in the Hoover Archives.) In 1969, Mayor Joseph Alioto appointed Hoffer to the San Francisco Arts Commission. But the San Francisco literary establishment never warmed to Hoffer because he had “praised America extravagantly,” he told a journalist toward the end of his life.

Finally, in November 1971, Hoffer moved to an efficiency apartment in a modern building, with a doorman, on Davis Place. A lifelong smoker, he suffered from emphysema. In 1977 he “dumped pipes, tobacco, cigars—more than $50 worth.” The apartment overlooked the docks where he had worked. And there he died. In his last notebook, written in 1981, he recorded: “Now and then it moves me to realize that in my last days I am living on the 17th floor of the Golden Gateway, a luxurious apartment building which occupies the site of the first Longshoremen’s Union hall from which I was dispatched 40 years ago—a dreary wet building situated in a typical gutter.”

The Writer and His Papers

Hoffer’s contact with the publishing world probably began in 1938, when he read an issue of Common Ground, a magazine then seeking to interpret America to immigrants. Hoffer put together his notes in the form of a long letter to the editor, Louis Adamic. In the Hoover Archives there is a 30-page article entitled “Tramps and Pioneers,” which is probably the article that Hoffer sent. The reply came from Adamic’s assistant, Margaret Anderson, who said they could not publish it. But she forwarded it to an editor at the publishing house Harper & Brothers. The editor there, Eugene Saxon, suggested to Hoffer that he write his autobiography and submit that. But Hoffer said he wasn’t interested in personal writing. There his literary career might have ended but for continued encouragement from Margaret Anderson. Eventually he sent the longhand manuscript of The True Believer to her, and she typed it and sent it to Harper & Brothers. (Three holograph drafts of The True Believer are in the Archives.)

One editor at Harper & Brothers, Evan Thomas, the son of Norman Thomas, considered the book “an extremely cynical work” and opposed publication. But another, John Fischer, found it “an important piece of original thinking and I very much hope we can work out a contract.” Published in March 1951, the book was dedicated to Margaret Anderson, “without whose goading finger which reached me across a continent, this book would not have been written.” Orville Prescott of the New York Times wrote that “Mr. Hoffer flings dogmatic judgments in all directions. . . . He also tosses off maxims and aphorisms with the aplomb of La Rochefoucauld himself.” One such aphorism, cited then and more recently, summarizes the thesis of The True Believer: “Faith in a holy cause is to a considerable extent a substitute for the lost faith in ourselves.”

In a 1941 letter to Anderson, Hoffer had written: “My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight, in the fields while waiting for a truck, and at noon after lunch. Towns are too distracting.” In 1949, he wrote to Anderson that, “by working [as a longshoreman] only Saturday and Sunday (18 hours at pay and a half) I earn 40–50 dollars a week. This to me is rolling in dough. I have no expensive tastes in food, clothing or pleasure. Above all, I have no taste for property.” (Letters from Anderson to Hoffer are in the Hoover Archives, but their full correspondence has not yet been located. The quotations above appeared in the New Yorker in 1951.)

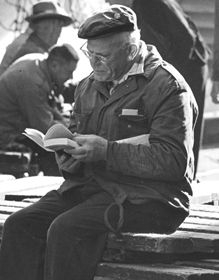

When not on the waterfront, Hoffer would take a regular three-mile walk in Golden Gate Park toward the Pacific Ocean, working out ideas in his head and writing down the completed thoughts in his notebooks. For perhaps 30 years, Hoffer took the same walk, returning to the center of the city by bus. “The words, the ideas, come to me in the park,” he said in a 1967 interview. “I shape them in my head there, and I write them in my notebook. Blind people [his sight had returned in adolescence] write full sentences in their head. Sentences they can see. I still do.” But 10 years later, when he was approaching 80, he wrote: “In the past I could carry a train of thought in my head for days, formulating and revising, without writing down a word until the thinking was done. At present I cannot write without pen in hand. . . . The old must break with the past and learn anew.”

The series of notebooks that Hoffer accumulated is perhaps the most important part of the Hoover collection, and of his unpublished writing. There are more than 130 such notebooks, dated from 1949 to 1977. Most of the material is unpublished, although Hoffer reviewed what he had written and mined it for works in progress. A good many of the thoughts and observations included in this large body of work were used in Hoffer’s later books and articles. But there is also much that is new. Extracting the latter from so large a manuscript would be a considerable editorial task, but a major new work by Hoffer could result.

The early notebooks show that he was at first contemplating a second volume of The True Believer. Of particular interest, in light of subsequent developments, are his reflections on Jews, Arab history, and developments in the Middle East. Hoffer was strongly pro-Israel and was more interested in the Jews and in their influence on history than his published work indicates. Four entries from these notebooks will give the reader a flavor:

• You must read more about early Islam. The Muslim fanaticism was perhaps of a different nature from Christian fanaticism. The conversion to Islam was altogether different from the conversion to Christianity. (1950)

• The Muslim sea of open mouths does not roar hatred but clamors for pride. [In Iran], Mossadegh’s defiance of the world is manna and ambrosia to souls starved for pride. (1952)

• The central fact is that the Arabs do not want peace proposals. They don’t want concessions. They want Israel destroyed. (1977)

• Sadat’s assassination made many things clear. The almost unemotional reaction of the Egyptian masses, so unlike that at the death of Nasser, suggested that the Arabs are affected more deeply by the pride of Arabism cultivated by Nasser than by the Egyptian nationalism and idealism advanced by Sadat. Anti-Israeli policies will have a powerful appeal in the Middle East for the balance of the century. It will be suicidal for the Israelis to believe in the possibility of a deep popular change. (1981)

Throughout his life, Hoffer would also copy onto file cards quotations from whatever he was reading. The thousands of cards that he accumulated, along with the metal cabinets in which they were stored, represent an attempt to compile the wisdom of the ages in aphoristic form, and they show remarkable energy, self-confidence, and ambition. Looking at them now, one can only marvel that the man who so painstakingly copied out these quotations also worked as a longshoreman. Most of us never get around to reading half the books that Hoffer read, let alone stopping in midpage to record the passages that interest us.

Shortly before he retired from the waterfront, Hoffer became an adjunct professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He was not looking forward to retirement, and his old friend Selden Osborne helped him out, contacting Norman Jacobson of the political science department. Jacobson arranged for Hoffer to visit campus once a week (in an office at the top of Barrow Hall). Often he would take a handful of his index cards with him and discuss the quotations with the students who showed up.

Toward the end of his life Hoffer returned to these quotations and assembled a collection of them, along with his own response or comment. Eventually a manuscript was completed and typed in a large font, to accommodate Hoffer’s failing eyesight. Titled “Quotations and Comments,” it consists of 209 pages. By then Hoffer was “struggling to write,” Lili Osborne notes on an attached sheet, and he was losing confidence in his power of thinking. In the end the manuscript was never submitted for publication.

Also worth noting are the manuscripts of early fiction, notably “Four Years in Hank’s Young Life.” The typed manuscript (170 pages) suggests that Hoffer considered it for publication, as he never typed. Several other fiction pieces were adapted in somewhat different form for Truth Imagined, Hoffer’s memoir (published posthumously in 1983). Hoffer’s fictional work is undated, but it was probably written in the 1930s. It testifies to his powers of observation and imagination and his storytelling abilities.

As he was composing Truth Imagined, “it was hard for him to breathe, see, think,” Lili Osborne wrote in a 1992 note. “But little by little he put this precious manuscript together. He returned to his earliest writings, long before The True Believer. . . . When he sent it off to Harper’s, he knew it was the end.”

There are a number of other unpublished manuscripts of magazine-article length, evidently considered by Hoffer as finished material; there are still other articles that were published in magazines but not included in Hoffer’s books. Particularly worth noting is the complete set of Hoffer’s newspaper column, “Reflections,” which he wrote almost every week for two years (1968–1969) for the Ledger Syndicate.

The Enigmatic Philosopher

About Eric Hoffer there is an element of mystery that the material in the Hoover Archives never dispels. He appears, with his talent fully developed, in his first work. Nothing is really explained. The roots from which his genius grew remain concealed. Some scraps of information seem more mythical than real (“My writing is done in railroad yards while waiting for a freight, in the fields while waiting for a truck”) and suggest a budding Jack Kerouac more than an Eric Hoffer—two writers who could not have been more different. Perhaps in his index cards more than anywhere else we see traces of the struggle, labor, and self-discipline that went into his writing.

Hoffer was always identified with the honorific “philosopher,” and he was one; but he more resembles the philosophers and prophets of old, especially in the high valuation that he always placed on his own independence. He saw himself as one who was free to tell the truth without fear of patron, publisher, department head, or tenure committee. “My first book was also my best, and the first thing published,” he wrote at the end of his life. “I never belonged to a circle or clique. I did not know I was writing a book until it was written. When my first book was published, there was no one near me, an acquaintance let alone a friend, to congratulate me.”

In a comment on his own abilities, a note of self-disparagement turns into an artful critique of professional philosophy. “I could never figure out—or probably did not take the trouble to figure out—what the great philosophical problems are about,” he wrote in 1977. “The momentous statements I come across are at best a storm in a teacup. There are quite a number of people who have a vested interest in the stuff [and] make a noble living out of it.”

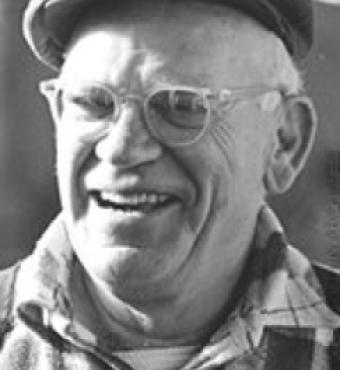

Above all, Hoffer was a stylist. Perhaps this extended to his dress, with his cloth cap in place and his dark green Filson’s jacket, with its pockets galore suitable for the pen and notebooks that he always carried. In print, he was original and lucid, the substance of his argument always given weight by the force of his style. Always self-aware, he recognized this himself. In a late notebook (1977) he wrote:

"Practically all artists and writers are aware of their destiny and see themselves as actors in a fateful drama. With me, nothing is momentous: obscure youth, glorious old age, fateful coincidences—nothing really matters. I have written a number of good sentences. I have kept free of delusions. I am going to die soon."