When it comes to pension funding, Californians should be able to get a straight answer to the following question: How much have the state and municipal governments promised to pay California public employees upon their retirements?

However, pension plan administrators, researchers, and politicians offer wildly different answers.

Why? Here’s a primer:

Defined Benefit Plans

First, there’s an inherent level of uncertainty surrounding the amount a given retiree will receive in pension payments, and thus how much the government needs to set aside today to pay all retirees later (the total liability).

California’s government employers generally offer defined benefit pensions plans, meaning that they promise to pay each retiree a certain amount each month for the rest of the retiree’s life. Variable retirement ages (governments often incentivize early retirement) and rising life expectancy rates make it difficult for even one entity to nail down an accurate estimate of how long an individual will receive pension payments, and thus how much the government will pay out overall.

In contrast, most private sector employers offer defined contribution plans (e.g. 401(k) plans), under which an employer and employee contribute set amounts to the plan as the employee works. When the employee retires, he or she simply receives the money that has been previously set aside in an account, which eliminates estimate inaccuracies.

Different Assumptions

Second, the amounts that governments will have to contribute to pensions in the future depend on assumptions about the future investment performance of existing assets. CalSTRS (K-12), and UCRP (University of California), and CalPERS (most other state employees), manage pensions by investing contributions from employers and employees and by reinvesting returns on their assets.

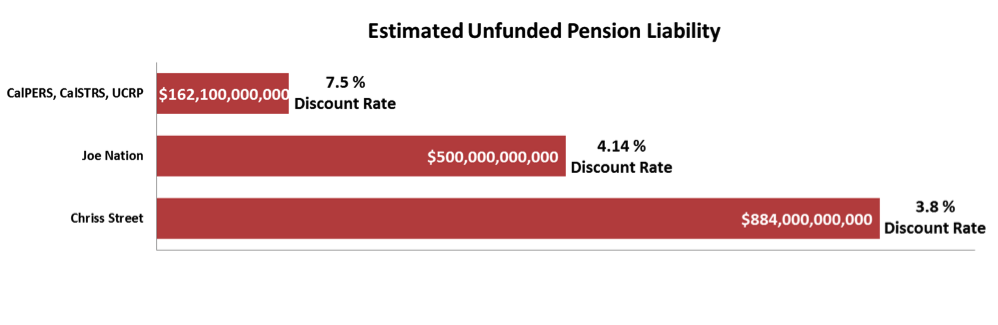

Varying assumptions about the future performance of those investments and whether performance should have any bearing on the value of liabilities account for a great deal of the disparity in liability estimates. Thus estimates of California’s unfunded liability range from the pension funds’ own $162 billion estimate, to critical outside analysts’ estimates of $500 billion to $884 billion.

One of the various assumptions: the discount rate. The discount rate determines the current value of the state’s liability, or how much funding it needs to have today to cover its future obligations. Calculating the value of the liability using a lower discount rate corresponds to a larger amount of funding that must be set aside today.

One of the various assumptions: the discount rate. The discount rate determines the current value of the state’s liability, or how much funding it needs to have today to cover its future obligations. Calculating the value of the liability using a lower discount rate corresponds to a larger amount of funding that must be set aside today.

Until earlier this year, CalPERS and CalSTRS used 7.75% and 8% discount rates, respectively. All three state plan managers now use 7.5% discount rates, which they set to be equal to their assumed rates of return on their investments. Essentially, the funds assume that their assets will gain 7.5% in value each annually and that they can discount their liabilities at that same rate.

Some critics argue that discounting liabilities at 7.5% is appropriate as long as assets in fact earn 7.5% value in the long run. Once those invested assets fail to gain that expected rate of return, the pension funds fall further and further behind their funding requirements and become “underfunded.”

Other critics argue that set payments from the pension fund are promised to retirees, and nearly impossible to avoid. Therefore, lower discount rates would better reflect how unlikely it would be for the state to not make its pension payments. These critics generally recommend using a discount rate around 4% - 5%, closer to what low-risk bonds generally earn.

CalPERS announced that, over the course of the 2012 fiscal year, it had earned only 1% on its investments. CalSTRS announced that it had performed only slightly better by managing a 1.8% return.

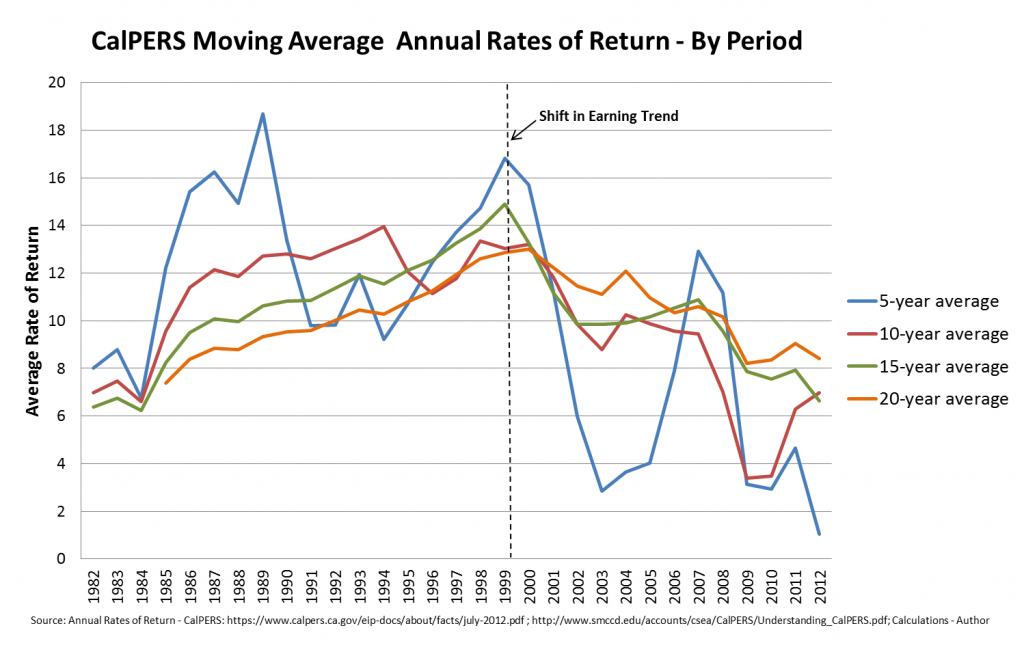

During the last decade, CalSTRS has averaged a 5.5% annual rate of return and CalPERS has averaged 7.0%. And for CalPERS, its 5-year, 10-year, 15-year, and 20-year average annual rates of return have all been trending downward since 1999, as illustrated in the chart below. From 1982-1998, CalPERS’s averaged a 13.4% average annual rate of return, but from 1999-2012, it has averaged only 5.7%.

Based on their 7.5% discount rate assumptions, CalPERS, CalSTRS, and UCRP estimate that their unfunded liabilities total $162 billion.

Through Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), former Democratic Assemblyman Joe Nation and former Special Adviser to Gov. Schwarzenegger David Crane have advocated for the use of a lower discount rate. In early 2010, Nation oversaw a research team that estimated a $500 billion (and growing) unfunded liability by using a 4.14% discount rate. In February 2010, 4.14% was the yield-to-maturity (YTM) of 10-year US Treasury Bills, and the team considered it the best representation of a risk-free rate.

Last August, CalPERS announced its decision to use a lower 3.8% discount rate for employers that leave CalPERS and terminate their pension plans. When employers withdraw from CalPERS, the plan must maintain funding for benefits already guaranteed, but only earned interest continues to fund the plan. CalPERS argued, “Our decision to set the discount rate for the terminated agency pool at 3.8% is based on the prudent strategy of reducing risk by investing more conservatively. By investing more conservatively, CalPERS is protecting a fund that has no other source of income other than interest.”

Conversely, Chriss Street, former treasurer of Orange County, argued, “If the California state pension plans adopted the same 3.8% rate they are only willing to credit when participants want to leave, their published $288 billion in pension shortfall would metastasize into an $884 billion California state insolvency [unfunded liability].”

With estimates using discount rates ranging anywhere from 3.8% to 8%, it’s no wonder that there’s so much disagreement about what the state actually owes retirees and how much it should be setting aside annually.

Ultimately, underestimating actual investment performance will mean that annual contributions are not sufficient to cover pension costs. The general consensus is that those funds will come from other areas of operating budgets throughout the state. That is a reality that policy makers need to consider seriously.

Autumn Carter is the Executive Director of California Common Sense, a nonpartisan non-profit research organization dedicated to making California’s government accessible to its citizens.